Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (PNETs) are uncommon tumors with a range of clinical behavior. Some PNETs are associated with symptoms of hormone secretion, with increased systemic levels of insulin, gastrin, glucagon, or other hormones. More commonly, PNETs are nonfunctional, without hormone secretion. Surgical resection is the mainstay of therapy, particularly for localized disease. Surgical therapy must be tailored to tumor and clinical characteristics. Resection may be particularly indicated in the setting of hormone hypersecretion. Small, incidental PNETs are increasingly managed nonoperatively. Surgery may also be indicated in some instances of metastatic disease, if all metastatic foci may be removed.

Key points

- •

Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors are relatively rare and make up approximately 1% to 2% of all solid pancreatic tumors.

- •

They include a diverse group of neoplasms, with clinical behavior ranging from small indolent tumors to widely metastatic disease.

- •

A minority are associated with hormone secretion and syndromes of hormone excess.

- •

Surgery is the treatment of choice for localized disease and may include formal pancreatic resection or parenchyma-preserving enucleation in some cases.

- •

Surgical care must be individualized to tumor characteristics and clinical symptoms.

Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (PNETs) are relatively rare, constituting approximately 1% to 2% of all pancreatic neoplasms and with an overall incidence of approximately 5 cases per million annually. Despite sharing histologic characteristics with neuroendocrine tumors from other sites, PNETs have unique biology and clinical behavior from other neuroendocrine neoplasms. These tumors include a heterogeneous group of neoplasms that have long been held in unique fascination by physicians and surgeons because of the ability of some tumors to secrete specific hormones and their association with well-described clinical syndromes. Most PNETs, however, do not secrete specific hormones and are often referred to as nonfunctioning PNET. Recent years have seen an increased understanding of the origin and biological basis of PNETs as well as in new targeted therapies for advanced PET. Surgical resection remains the mainstay of therapy for localized and occasionally metastatic disease.

In addition to their relatively rare incidence and diverse clinical manifestations, PNETs have a wide range of biological behavior and associated prognosis. Although many PNETs are relatively slow growing and have a favorable long-term prognosis, others may present with locally invasive or metastatic disease. Furthermore, some PNETs may present in association with genetic syndromes, such as multiple endocrine neoplasia type I (MEN1), that will influence rates of recurrence. This variability in biological behavior and recurrence risk precludes a unified treatment strategy for all PNETs. Unique surgical considerations for functioning and nonfunctioning PNETs, both localized and metastatic, are considered.

Clinical presentation and diagnosis

Functioning Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors

PNETs are classified as functional based on secretion of one of a variety of hormones, including insulin, gastrin, glucagon, vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP), and rarely somatostatin. The clinical presentation and evaluation of these are specific to each type of tumor.

Insulinoma

Given the unregulated production of insulin, patients with insulinoma will typically present with signs and symptoms of hypoglycemia, including neuroglycopenic or sympathetic effects. Neuroglycopenic symptoms may include headaches, blurred vision, forgetfulness, and difficulties with speech. Activation of the sympathetic nervous system can result in sweating, tachycardia, tremors, and weakness. Both neuroglycopenic and sympathetic symptoms may be relieved with eating. Excess caloric intake coupled with the anabolic effects of insulin often leads to weight gain in these patients.

Diagnosis of insulinoma is traditionally suspected based on the combination of clinical signs, known as Whipple’s triad in recognition of the original description of these tumors by Whipple and Frantz in 1935. This triad consists of the presence of symptomatic hypoglycemia with fasting, documented plasma glucose of less than 50 mg/dL with symptoms, and the relief of symptoms with glucose administration. Diagnosis is confirmed by assessment of serum insulin, proinsulin, C-peptide, and glucose to establish hyperinsulinism ; the absence of ketosis or sulfonylurea metabolites in blood or urine is important to rule out factitious hyperinsulinism. Within 48 hours of an observed fast, between 90% and 95% of patients will develop hypoglycemia, with a diagnostic insulin-to-glucose ration of more than 0.4. Although far less common than insulinoma, adult nesidioblastosis or beta cell hyperplasia will occasionally present with similar laboratory and clinical findings. This syndrome has been described in a population of patients after bariatric surgery.

In the absence of a clinical syndrome such as MEN1, most insulinomas occur as small, solitary, benign lesions. Although tumors may range in size, most are less than 2 cm in size and can be found with relatively equal distribution throughout the pancreas. Very few patients with insulinoma develop metastatic spread, with a rate of less than 10%, far less than other pancreatic islet cell tumors.

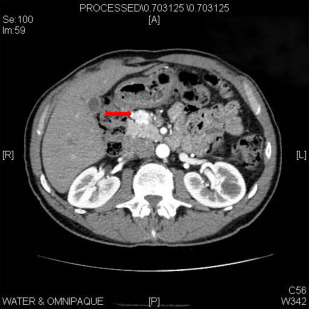

Although selective pancreatic angiography with calcium stimulation and hepatic venous sampling was traditionally used to detect these small lesions, contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) can localize most lesions ( Fig. 1 ). Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) is quite sensitive for the detection of insulinoma, and the combination of EUS with CT can identify nearly all lesions. Conventional MRI is similarly sensitive in this setting. The use of somatostatin receptor scintigraphy is limited given the low expression of type 2 somatostatin receptors on insulinomas.

Gastrinoma

The identification of patients with severe ulcer disease and associated non–insulin-producing islet cell tumors led to the description of gastrinomas by Zollinger and Ellison in 1955. Gastrinomas are associated with MEN1 in approximately 25% of cases and develop metastatic disease in 60% to 90%. Patients may present with disabling pain, diarrhea, reflux, and duodenal ulcers.

Hypergastrinemia in the setting of excess gastric acid secretion is important to rule out atrophic gastritis or proton pump inhibitor use. Secretin stimulation causes a paradoxic increase in serum gastrin in the setting of a gastrinoma, which can be used to diagnose the tumors.

Gastrinomas are frequently multifocal, with a higher propensity for local or distant spread than insulinoma. Most are localized in an area referred to as the gastrinoma triangle, delineated by the junction of the cystic duct and common bile duct, the body and neck of the pancreas, and the second and third portion of the duodenum. Localization of tumors may be challenging with traditional cross-sectional imaging, though somatostatin receptor scintigraphy has a sensitivity of approximately 60%. In some cases, operative exploration can be required to identify lesions using palpation, intraoperative ultrasound, duodenotomy, and transillumination of the duodenum ( Fig. 2 ).

Glucagonoma

Glucagonoma is a rare functioning pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor associated with a range of signs, most characteristically a rash known as necrolytic migratory erythema, a vesicular, erythematous necrotic dermatitis. Patients present with diabetes, glossitis, weight loss, and weakness. Deep vein thrombosis can occur in 30% of patients, and patients present with anemia and a decreased level of amino acids due to gluoneogensis. These tumors are often large at diagnosis, and contrast-enhanced CT scan is often sufficient for localization. Patients often present with advanced and metastatic disease.

VIPoma

Vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIPoma) are exceedingly rare tumors associated with secretion of the hormone VIP. The syndrome of copious watery diarrhea, hypokalemia, and achlorhydria is also described as pancreatic cholera. These tumors are characteristically large and are often metastatic to the liver at the time of diagnosis. Most are easily visualized by contrast-enhanced CT or somatostatin receptor scintigraphy.

Nonfunctioning Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors

Approximately 70% of PNETs do not secrete a specific hormone and are not associated with specific clinical syndromes. These tumors are often asymptomatic in the absence of vague abdominal pain. Although symptoms may include abdominal pain, jaundice, pancreatic insufficiency, a palpable mass, and anorexia, tumors are often detected before symptoms as incidental finding on imaging studies performed for an unrelated indication. In one 20-year cohort of nonfunctioning PNET, 35% of patients were asymptomatic with an incidental diagnosis. Patients with advanced disease may present with locally advanced disease involving the mesenteric vessels or with widespread metastases.

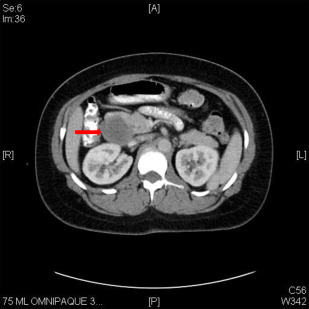

PNETs typically appear as hypervascular lesions on CT, as opposed to the often hypovascular appearance of adenocarcinoma. MRI has a comparable sensitivity and specificity ( Fig. 3 ). Somatostatin-receptor scintigraphy has excellent sensitivity and specificity and is particularly important for evaluating the presence of occult metastatic disease. Definitive diagnosis can often be obtained with EUS-guided fine-needle aspiration. Serum chromogranin A is a valuable tumor marker in the management of well-differentiated PNETS, and levels can be used in determining response to therapy and for serial follow-up of patients.

Clinical presentation and diagnosis

Functioning Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors

PNETs are classified as functional based on secretion of one of a variety of hormones, including insulin, gastrin, glucagon, vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP), and rarely somatostatin. The clinical presentation and evaluation of these are specific to each type of tumor.

Insulinoma

Given the unregulated production of insulin, patients with insulinoma will typically present with signs and symptoms of hypoglycemia, including neuroglycopenic or sympathetic effects. Neuroglycopenic symptoms may include headaches, blurred vision, forgetfulness, and difficulties with speech. Activation of the sympathetic nervous system can result in sweating, tachycardia, tremors, and weakness. Both neuroglycopenic and sympathetic symptoms may be relieved with eating. Excess caloric intake coupled with the anabolic effects of insulin often leads to weight gain in these patients.

Diagnosis of insulinoma is traditionally suspected based on the combination of clinical signs, known as Whipple’s triad in recognition of the original description of these tumors by Whipple and Frantz in 1935. This triad consists of the presence of symptomatic hypoglycemia with fasting, documented plasma glucose of less than 50 mg/dL with symptoms, and the relief of symptoms with glucose administration. Diagnosis is confirmed by assessment of serum insulin, proinsulin, C-peptide, and glucose to establish hyperinsulinism ; the absence of ketosis or sulfonylurea metabolites in blood or urine is important to rule out factitious hyperinsulinism. Within 48 hours of an observed fast, between 90% and 95% of patients will develop hypoglycemia, with a diagnostic insulin-to-glucose ration of more than 0.4. Although far less common than insulinoma, adult nesidioblastosis or beta cell hyperplasia will occasionally present with similar laboratory and clinical findings. This syndrome has been described in a population of patients after bariatric surgery.

In the absence of a clinical syndrome such as MEN1, most insulinomas occur as small, solitary, benign lesions. Although tumors may range in size, most are less than 2 cm in size and can be found with relatively equal distribution throughout the pancreas. Very few patients with insulinoma develop metastatic spread, with a rate of less than 10%, far less than other pancreatic islet cell tumors.

Although selective pancreatic angiography with calcium stimulation and hepatic venous sampling was traditionally used to detect these small lesions, contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) can localize most lesions ( Fig. 1 ). Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) is quite sensitive for the detection of insulinoma, and the combination of EUS with CT can identify nearly all lesions. Conventional MRI is similarly sensitive in this setting. The use of somatostatin receptor scintigraphy is limited given the low expression of type 2 somatostatin receptors on insulinomas.

Gastrinoma

The identification of patients with severe ulcer disease and associated non–insulin-producing islet cell tumors led to the description of gastrinomas by Zollinger and Ellison in 1955. Gastrinomas are associated with MEN1 in approximately 25% of cases and develop metastatic disease in 60% to 90%. Patients may present with disabling pain, diarrhea, reflux, and duodenal ulcers.

Hypergastrinemia in the setting of excess gastric acid secretion is important to rule out atrophic gastritis or proton pump inhibitor use. Secretin stimulation causes a paradoxic increase in serum gastrin in the setting of a gastrinoma, which can be used to diagnose the tumors.

Gastrinomas are frequently multifocal, with a higher propensity for local or distant spread than insulinoma. Most are localized in an area referred to as the gastrinoma triangle, delineated by the junction of the cystic duct and common bile duct, the body and neck of the pancreas, and the second and third portion of the duodenum. Localization of tumors may be challenging with traditional cross-sectional imaging, though somatostatin receptor scintigraphy has a sensitivity of approximately 60%. In some cases, operative exploration can be required to identify lesions using palpation, intraoperative ultrasound, duodenotomy, and transillumination of the duodenum ( Fig. 2 ).

Glucagonoma

Glucagonoma is a rare functioning pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor associated with a range of signs, most characteristically a rash known as necrolytic migratory erythema, a vesicular, erythematous necrotic dermatitis. Patients present with diabetes, glossitis, weight loss, and weakness. Deep vein thrombosis can occur in 30% of patients, and patients present with anemia and a decreased level of amino acids due to gluoneogensis. These tumors are often large at diagnosis, and contrast-enhanced CT scan is often sufficient for localization. Patients often present with advanced and metastatic disease.

VIPoma

Vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIPoma) are exceedingly rare tumors associated with secretion of the hormone VIP. The syndrome of copious watery diarrhea, hypokalemia, and achlorhydria is also described as pancreatic cholera. These tumors are characteristically large and are often metastatic to the liver at the time of diagnosis. Most are easily visualized by contrast-enhanced CT or somatostatin receptor scintigraphy.

Nonfunctioning Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors

Approximately 70% of PNETs do not secrete a specific hormone and are not associated with specific clinical syndromes. These tumors are often asymptomatic in the absence of vague abdominal pain. Although symptoms may include abdominal pain, jaundice, pancreatic insufficiency, a palpable mass, and anorexia, tumors are often detected before symptoms as incidental finding on imaging studies performed for an unrelated indication. In one 20-year cohort of nonfunctioning PNET, 35% of patients were asymptomatic with an incidental diagnosis. Patients with advanced disease may present with locally advanced disease involving the mesenteric vessels or with widespread metastases.

PNETs typically appear as hypervascular lesions on CT, as opposed to the often hypovascular appearance of adenocarcinoma. MRI has a comparable sensitivity and specificity ( Fig. 3 ). Somatostatin-receptor scintigraphy has excellent sensitivity and specificity and is particularly important for evaluating the presence of occult metastatic disease. Definitive diagnosis can often be obtained with EUS-guided fine-needle aspiration. Serum chromogranin A is a valuable tumor marker in the management of well-differentiated PNETS, and levels can be used in determining response to therapy and for serial follow-up of patients.

Staging

The World Health Organization classifies neuroendocrine tumors into different grades based on histologic characteristics. Well-differentiated tumors include low-grade (G1) tumors with a low mitotic count and Ki-67 proliferative index of less than 3% as well as intermediate-grade (G2) tumors with mitotic counts of 2 to 20 per high-power field (HPF) and Ki-67 rate of 3% to 20%. Poorly differentiated tumors or high-grade (G3) tumors have mitotic rates more than 2 per 10 HPF and Ki-67 rate of greater than 20%. High-grade tumors, often referred to as neuroendocrine carcinomas, display more aggressive clinical behavior and unlike, well-differentiated tumors, are generally not candidates for surgical resection.

Staging systems include variants proposed by the American Joint Committee on Cancer and a second promoted by the European Neuroendocrine Tumor Society. Both systems are useful for predicting survival, with overall survival ranging from 90% to 100% at 5 years for stage I tumors to approximately 60% for stage IV tumors.

Surgical management

Functioning Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors

Insulinoma

Although surgical resection of localized disease is the mainstay of therapy for all PNETs, insulinomas are unique in their relative lack of metastases and potential for treatment with pancreas-sparing procedures. Unlike formal pancreatic surgery, such as distal pancreatectomy, central pancreatectomy, or pancreaticoduodenectomy, enucleation involves removal of just the tumor and associated capsule, sparing otherwise normal pancreatic parenchyma ( Fig. 4 ). In a systematic review of case series with a total of more than 6200 insulinoma patients, Mehrabi and colleagues describe enucleation as the procedure of choice in more than half of insulinomas.

Enucleation is particularly applicable to small, benign, superficial tumors. Tumors closer to the main pancreatic duct will have a higher risk of postoperative pancreatic fistula after enucleation. Tumors located deeper in the parenchyma, larger tumors, or tumors with any suspicion of malignancy are more appropriately treated with formal resection. Enucleation is also well described using minimally invasive or laparoscopic techniques. The use of intraoperative ultrasound should be routine in either open or laparoscopic cases to identify the distance between the tumor and the main pancreatic duct and to exclude multiple tumors. Given the benign behavior of most insulinomas, lymph node dissection is not required as part of the procedure.

In rare instances, a thorough evaluation has failed to identify the location of an insulinoma; it was thought that blind distal pancreatectomy would remove most occult lesions. This procedure is now rarely performed because of improved localization techniques. In cases of truly undetected lesions, it is more appropriate to stop the operation and seek more accurate localization.

Surgery for insulinoma in the presence of MEN1 is aimed at controlling all excess insulin secretion by removing all possible tumor burden. Preoperative localization is essential given the propensity for multifocal disease ( Box 1 ).