Complete lymphadenectomy is currently the standard treatment for melanoma patients with identified regional nodal metastases. As a general principle, lymphadenectomy should be anatomic. The contents of the nodal basin are excised in a single block of tissue, preserving motor nerves and muscle whenever possible. Perioperative antibiotics are used routinely.1

The goals of surgery include staging, regional control of disease, and possibly improved survival for some patients with clinically occult metastases identified by sentinel node biopsy. Indeed, the majority of patients who undergo lymphadenectomy today are now those who have histologically positive sentinel nodes. According to evidence-based ASCO/SSO guidelines, “completion lymph node dissection (CLND) is recommended for all patients with a positive SLN biopsy and achieves good regional disease control. CLND should be performed until there is convincing evidence that it does not improve regional disease control or survival.”2

Patients with clinically suspicious nodes should be evaluated by fine-needle biopsy, if possible, with excisional biopsy done only if the results of fine-needle biopsy are indeterminate. Patients with bulky, biopsy-proven, nodal disease should be evaluated with baseline CT scans, a full blood count, and measurement of liver enzymes, including LDH, to rule out identifiable distant disease before proceeding with nodal surgery.

The following sections describe some technical principles of lymphadenectomy in the axillary, ilioinguinal, and cervical regions.

The goal of axillary lymph node dissection for melanoma is complete resection of all lymph nodes at levels I, II, and III.3 The long thoracic nerve and the thoracodorsal neurovascular bundle are left intact unless they are directly invaded by tumor. While division of the pectoralis minor muscle is rarely considered necessary for breast cancer, it is sometimes used for melanoma patients in order to obtain complete exposure of level II and III nodes. After removal of the axillary contents, a closed-suction drain is placed. Further details about surgical technique are described elsewhere.3 Patients undergoing a radical axillary lymphadenectomy should have no appreciable loss of range of motion or motor function. After a complete axillary dissection for melanoma there is approximately a 5% to 10% risk of symptomatic lymphedema of the upper extremity.

For patients with metastatic nodes in the groin, an anatomically complete subinguinal (inguinofemoral) dissection is performed.4,5 In most cases a vertical incision is used, often with wide excision of an ellipse of skin over the femoral vessels, an area inevitably devascularised to some degree by the subsequent dissection. Flaps are then raised. The boundaries of the dissection extend superiorly to approximately 5 cm above the inguinal ligament, medially to the pubic tubercle and the midbelly of adductor longus, laterally to the anterior superior iliac spine and the lateral border of sartorius, and inferiorly to the apex of the femoral triangle. In patients with clinically detected nodal metastases, the femoral canal is explored from below and Cloquet’s node is removed. This step can be omitted in patients undergoing completion node dissection following detection of clinically occult or microscopic nodal disease. If there is concern about the possibility of wound breakdown, the sartorius muscle may be taken down from its insertion into the anterior superior iliac spine, rotated over the femoral vessels to cover and protect them, and tacked in place to the edge of the inguinal ligament and the fascia of the adductor longus. A closed-suction drain is placed in the inguinofemoral area prior to closure. Although prophylactic antibiotics are usually given, inguinal dissection wounds have an infection rate of up to 15%. The risk of symptomatic lymphedema of the lower extremity is approximately 20%. Routine measures aimed at reducing the risk of lymphedema include a program of wearing a fitted compression garment at 20 to 30 mm Hg during the day for the first 3 to 6 months postoperatively, and leg elevation when possible.

Indications for iliac and obturator node dissection include the finding of a positive Cloquet’s node intraoperatively or the detection of enlarged iliac or obturator nodes on preoperative CT scans, or fludeoxyglucose (FDG)-avid iliac or obturator nodes on a PET scan. The boundaries of the dissection are from the bifurcation of the common iliac vessels superiorly to the inguinal ligament inferiorly and to the obturator vessels medially. Technical details of iliac and obturator node clearance are given elsewhere.6

The extent of cervical lymphadenectomy depends on the location of the metastatic node or nodes and whether there is evidence of direct invasion into the structures of the neck. When a metastatic sentinel node is found, a functional neck dissection preserving the internal jugular vein, spinal accessory nerve, and sternal head of sternocleidomastoid is appropriate. These structures should be sacrificed only if they are directly invaded by tumor.7 When there is clinical involvement of the parotid lymph nodes, the lymph nodes more inferiorly in the neck are also at risk of harboring metastatic disease, even if they are clinically negative. For this reason, a neck dissection is generally performed in addition to a therapeutic parotidectomy.7 Conversely, patients with clinically evident cervical node metastases arising from a melanoma located on the ipsilateral face, anterior scalp, or ear should have a superficial parotidectomy performed at the time of a comprehensive neck dissection, even if the parotid nodes are clinically negative, because there is a high risk of clinically occult nodal disease in the parotid area.

A therapeutic neck dissection is associated with a 20% to 30% recurrence rate in the neck. Patients with multiple metastatic nodes, especially those with gross extracapsular invasion into surrounding tissues, have a particularly high risk of neck recurrence, even after a thorough neck dissection. When this occurs, there can be severe morbidity. Many centers therefore recommend adjuvant postoperative radiation therapy after a neck dissection for clinically palpable nodal metastases in the neck, especially when the nodes are large or multiple and when there is extranodal extension of tumor.8 (See Chapter 17.) This has been shown in a randomized trial to reduce substantially the risk of node field recurrence.9

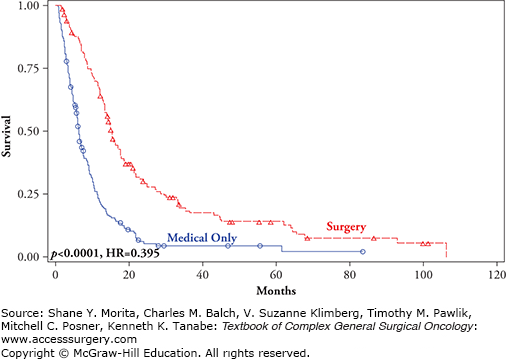

Surgery for advanced melanoma is most effective when disease is limited to a few sites and a small number of metastases. Surgical excision of isolated metastatic lesions can provide effective and quick palliation and, in some instances, a survival exceeding 5 or 10 years.10–12 The favorable outcome resulting from surgical resection of distant metastases in selected patients treated at major centers13–19 (Table 15-1). Possibly the best outcomes data available are from MSLT1 patients who were followed prospectively for relapse at distant sites10. Of the 291 patients with a stage IV recurrence, 161 (55%) underwent surgery, with or without systemic medical therapy (SMT). Median survival was 15.8 versus 6.9 months, and 4-year survival was 20.8 versus 7.0% for patients receiving surgery with or without SMT versus SMT alone (p < 0.0001; HR 0.406) (Table 15-2 and Fig. 15-1). Patients who had one metastasis, regardless of site, had a significant survival advantage compared to patients undergoing surgery for three or more metastases (Fig. 15-2). Surgery, with or without SMT, conferred a survival advantage for patients with M1a (Fig. 15-3), M1b (Fig. 15-4), and M1c diseases (Fig. 15-5). It was concluded that approximately half of patients who progress to stage IV disease might be candidates for surgical excision, especially those with a single metastasis, and those with M1a or M1b disease10. It should be emphasized that the results of these studies cannot distinguish between the relatively more favorable biology of limited metastases and the treatment impact of surgical excision in the absence of randomized studies. In general, however, they consistently demonstrate the importance of completely resecting all distant metastases (compared to incomplete resection) with regard to survival outcome.

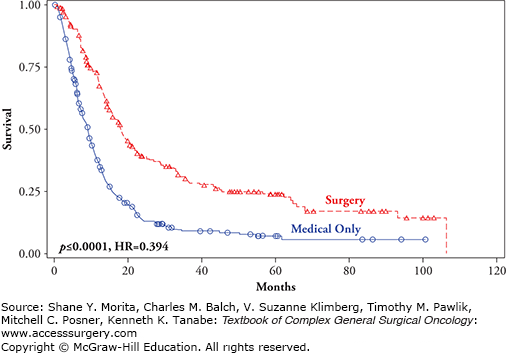

FIGURE 15-1

Survival for MSLTI patients treated surgically and medically for stage IV melanoma recurrence (p < 0.0001, HR = 0.394).10

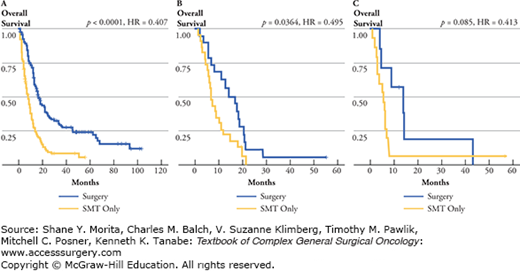

FIGURE 15-2

Overall survival (months) for MSLT1 patients who progressed to stage IV and were treated with surgical excision +/− standard medical therapy (blue lines) versus standard medical therapy only (yellow lines) analyzed by the number of stage IV metastases. A. One metastasis. B. Two metastases. C. Three or more metastases. (Reproduced with permission from Howard JH, Thompson JF, Mozzillo N, et al, Metastasectomy for distant metastatic melanoma: analysis of data from the first Multicenter Selective Lymphadenectomy Trial (MSLT-I), Ann Surg Oncol. August 2012;19(8):2547–2555.)

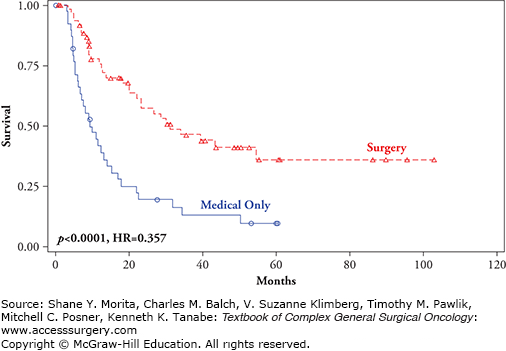

FIGURE 15-3

Overall survival by treatment and site of recurrence: M1a (skin, subcutaneous melanoma metastases) comparing surgical excision +/− standard medical therapy (red line) versus standard medical therapy only (blue line) (p < 0.0001, HR = 0.357).10

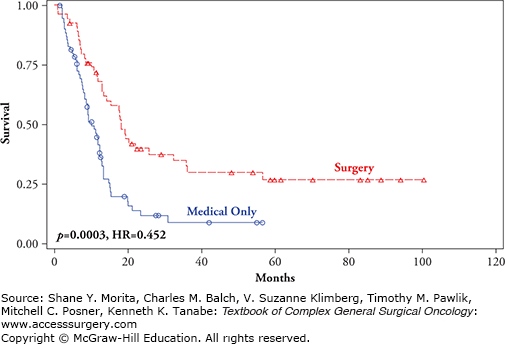

FIGURE 15-4

Overall survival by treatment and site of recurrence: M1b (lung metastases) comparing surgical excision +/− standard medical therapy (red line) versus standard medical therapy only (blue line) (p = 0.0003, HR = 0.452).10

FIGURE 15-5

Overall survival by treatment and site of recurrence: M1c (visceral metastases other than lung metastases) comparing surgical excision +/− standard medical therapy (red line) versus standard medical therapy only (blue line) (p < 0.0001, HR = 0.395).10

Results of Surgical Excision of Metastatic Disease from Different Published Seriesa,b

| Metastatic Site | John Wayne Cancer Institute18 | University of Alabama Hospitals19 | University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center22 | Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center17 | Roswell Park Memorial Institute15 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skin, subcutaneous | 24 (36)b | 17 (13)b | 23 (65)b | 25 (12)b | 31 (25)b |

| Lung | 19 (46) | 9 (17) | 16 (26) | 19 (17) | 9 (13) |

| Brain | 12 (17) | 8 (17) | 15 (16) | 7.5 (5) | 5 (4) |

| Gastrointestinal tract (nonhepatic) | 10 (19) | 8 (5) | 18 (9) | 15 (12) | 8 (3) |

| 2-Year survival rate (%) | 45 | 16 | 15 | 21 | 31 |

Median Survival (Months) from Diagnosis of Stage IV Melanomaa

| Extent of Metastasis (# patients) | Surgery | No Surgery | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median Survival | Percentage (n) | Median Survival | Percentage (n) | ||

| Involved organ sites (n) | |||||

| 1 (242) | 17.6 months | 60% (144) | 7.5 months | 40% (98) | <0.0001 |

| 2 (35) | 13.4 months | 40% (14) | 6.6 months | 60% (21) | 0.056 |

| ≥3 (14) | 4.5 months | 21% (3) | 4.8 months | 79% (11) | 0.36 |

| Individual metastases (n) | |||||

| 1 (226) | 16.3 months | 59% (134) | 7.5 months | 41% (92) | <0.0001 |

| 2 (43) | 17.1 months | 47% (20) | 6.9 months | 53% (23) | 0.0364 |

| ≥3 (22) | 13.9 months | 32% (7) | 5.2 months | 68% (15) | 0.085 |

Surgery should only be used when the risk of perioperative morbidity is acceptable. If the initial recurrence of melanoma is a solitary lesion, surgical resection should be considered the treatment of choice after a careful diagnostic workup for metastases at other sites.11 Surgery should also be the first consideration for patients with two to three metastases in a single organ, such as lung or skin and soft tissue. Patients with multi-organ metastases, such as to the lung, liver, and brain, are less suitable candidates for resection.

Surgical treatment to relieve symptoms caused by metastases is generally worthwhile, especially when the anticipated benefit from palliation exceeds the morbidity of the procedure, for example, resection of small bowel metastases to relieve bowel obstruction or gastrointestinal bleeding. Expectant (or prophylactic) palliation is used for control of disease that is likely to cause disabling symptoms. Although the survival associated with visceral metastases is generally worse than that associated with distant subcutaneous and nodal metastases when patients are treated with chemotherapy or IL2 therapy, the survival differences disappear if visceral metastases can be completely resected.14 In addition, long-term results demonstrate the value of sequential resection of distant metastases: Ollila et al reported a 19% rate of 5-year survival following complete resection for recurrence after initial metastasectomy.20

The skin, subcutaneous tissue, and nonregional lymph nodes are among the most common sites for distant metastatic melanoma.12,13,21 When metastases in these locations are few and isolated, surgical excision may be the safest, quickest, and most effective treatment. Lesions should be excised before they become bulky and symptomatic, when a more extensive operation would be required.18,22,23 When possible a rim of normal-appearing tissue (at least 1.0 cm, or >1.0 cm for larger lesions) should be removed to minimize the risk of local relapse. Sequential metastases in one area can be excised surgically unless they recur rapidly or extensively, or concurrently with metastases at other sites. In either situation (multiple lesions or sites), radiotherapy and/or systemic chemotherapy may be an alternative.

Excellent results have been obtained with surgical excision of skin, subcutaneous or distant lymph node metastases, especially when there are only a few lesions. Many such patients require repeated excisions, but the median survival from the onset of these metastases averages 2 years (range 3 to 180 months).11 The addition of hypofractionated radiation therapy after resection of nodal and subcutaneous melanoma deposits at a variety of sites has been reported to provide excellent local control,24 but is rarely necessary if the subcutaneous metastases are resected with adequate margins.11

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree