Surgical Management of Metastatic Bone Disease: Humeral Lesions

Jacob Bickels

Martin M. Malawer

BACKGROUND

The humerus is a common site of metastatic bone disease requiring surgery. A metastasis at that site, and especially one involving the dominant extremity, has an immediate and profound impact on the affected individual’s ability to perform activities of daily living. The quality of surgery, therefore, is an important determinant in restoring vital function.

A detailed preoperative clinical and imaging evaluation is mandatory for defining the morphologic characteristics of the lesion and, in turn, establishing the indication for surgical intervention as well as distinguishing between lesions that can be managed with curettage and cemented fixation and those which require resection with endoprosthetic reconstruction.2,3,5,6

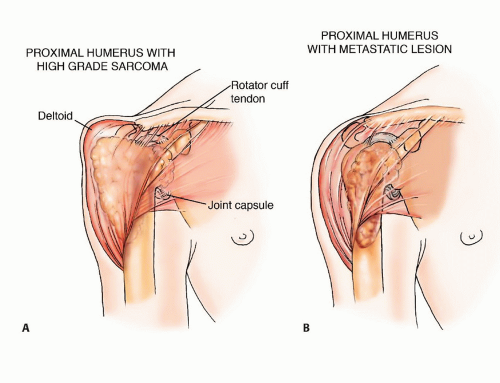

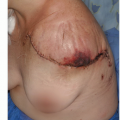

Unlike primary sarcomas of the humerus, metastatic tumors usually have a small soft tissue component, even in the presence of extensive bone destruction. This characteristic allows resection of bony elements only and the sparing of the extracortical structures, such as the joint capsule, overlying muscles, and muscle attachments, and affords the opportunity for using them to reconstruct and preserve function (FIG 1). To this end, exposure of the proximal humerus is done by splitting the deltoid muscle rather than using the deltopectoral interval, as is done in the case of a primary sarcoma of bone, which necessitates en bloc resection of the deltoid muscle with the tumor. Moreover, a few centimeters of upper limb shortening following resection of bone segment has minimal impact on function because a slight difference in positioning of that extremity in space can easily compensate for such limb length discrepancy.

In contrast, a similar discrepancy in the lower extremities that require almost equal length for normal gait would result in an inevitable limp, the extent of which would be proportional to the shortening of the operated extremity.2

ANATOMY

Proximal humerus: type I metastasis

Covered anteriorly and laterally by the deltoid muscle

Joint capsule encircles the humeral head and attaches to the base of anatomic neck.

Attachment site for the rotator cuff muscles. Long head of the biceps muscle crosses the anterior aspect within the bicipital groove.

Humeral diaphysis: type II metastasis

Upper half is occupied by muscle insertions:

Medial aspect—teres major, latissimus dorsi, coracobrachialis

Lateral aspect—pectoralis major, deltoid

Radial nerve curves at the back from medial to lateral at the midarm level

Lower half is occupied by muscle origins:

Medial aspect—brachialis

Lateral aspect—brachioradialis

Neurovascular bundle along its medial aspect

Distal humerus: type III metastasis

Neurovascular bundle along its medial aspect between the biceps and brachialis muscles

Radial nerve along its lateral aspect between the brachialis and brachioradialis muscles

INDICATIONS

Pathologic fracture

Impending pathologic fracture

Intractable pain associated with locally progressive disease that had shown inadequate response to narcotics and preoperative radiation therapy

Solitary bone metastasis in selected patients

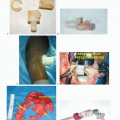

IMAGING AND OTHER STAGING STUDIES

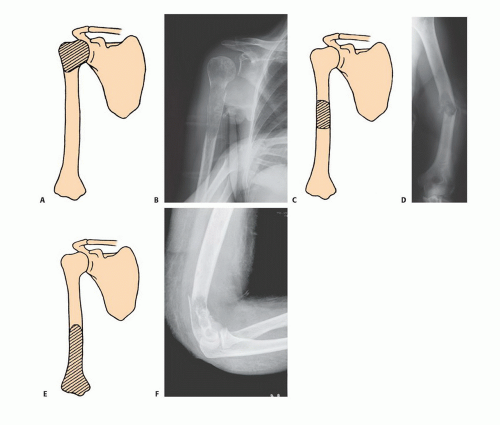

Plain radiographs of the entire humerus are mandatory to rule out synchronous metastases that may change the extent and technique of surgery. Computed tomography of the lesion will clearly define the extents of bone destruction and soft tissue component. Total body bone scintigraphy is done to detect synchronous metastases elsewhere in the skeleton. At the conclusion of imaging, the surgeon should be able to answer the following questions:

Are there additional humeral metastases and, if there are, can they be managed by nonoperative techniques or do they require surgery?

Are there additional skeletal metastases and, if there are, can they be managed by nonoperative techniques or do they require surgery?

What is the appropriate surgery? As a rule, the tumor curettage and cemented fixation approach is used for lesions in which the remaining cortices allow containment of the fixation device; otherwise, surgery involves resection of the affected bone segment with prosthetic reconstruction.

TECHNIQUES

▪ Types I and II Metastases

Position and Incision

The patient is placed in a semilateral position, and an anterior utilitarian shoulder girdle incision is made.

The incision begins at the junction of the inner and middle third of the clavicle and continues over the coracoid process, along the deltopectoral groove, and down the arm over the medial border of the biceps muscle (TECH FIG 1).

Exposure

The deltoid muscle is divided longitudinally to expose the humeral head and proximal third of the humeral diaphysis.

Exposure of the remaining diaphysis is achieved by similarly dividing the brachialis muscle.

Electrocautery and rasps are used to detach and reflect the periosteum and muscle attachments from the underlying cortex (TECH FIG 2).

Tumor Removal

Type I Metastasis

Using electrocautery, the rotator cuff tendons are detached from the humerus, the long head of the biceps is cut at its insertion site around the glenoid, and the joint capsule is opened.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree