Although papillary thyroid cancer (PTC) commonly metastasizes to cervical lymph nodes, prophylactic central neck dissection is controversial. The primary treatment for lymph node metastases is surgical resection. Patients diagnosed with PTC should be assessed preoperatively by cervical ultrasound to evaluate central and lateral neck lymph node compartments. Sonographically suspicious lymph nodes in the lateral neck should be biopsied for cytology or thyroglobulin levels. Any compartment (central or lateral) that has definitive proof of nodal metastases should be formally dissected at the time of thyroidectomy.

Key points

- •

When central or lateral compartment cervical lymph node metastases are clinically evident at the time of the index thyroid operation for PTC, formal surgical clearance of the affected nodal basin is the optimal management.

- •

Prophylactic central neck dissection for PTC is practiced by some high-volume surgeons with low complication rates, but is considered controversial because there appears to be a higher risk of complications with an uncertain clinical benefit.

- •

When a clinically significant recurrence is detected in a previously undissected central or lateral cervical compartment, a comprehensive surgical clearance of the lateral compartment is the preferred treatment.

- •

When a nodal recurrence is found in a previously dissected central or lateral neck field, the reoperation may focus on the areas where recurrence is demonstrated.

Introduction

In endocrine surgery, controversy abounds. It is difficult, in fact, to find a topic in surgical endocrinology for which there is little or no controversy. The management of cervical nodal metastases from papillary thyroid cancer (PTC) is no exception. Fortunately, there is widespread agreement regarding the management of clinically evident nodal metastases. It seems clear, based on the risks of persistent or recurrent disease, that the optimal management is formal surgical clearance of the affected nodal basin or basins when cervical nodal metastases are clinically evident at the time of the index thyroid operation. On the other hand, because of the high frequency and uncertain clinical significance of occult nodal metastases from PTC, considerable controversy surrounds the management of the clinically negative central compartment, and the performance of so-called prophylactic central neck dissection (CND). Likewise, there is uncertainty regarding the thresholds for recommending remedial CND, given the attendant risks of the procedure and uncertain benefits. Within this contribution to the Surgical Oncology Clinics of North America , the data relevant to the surgical management of the lymph nodes of the central and lateral compartments of the neck in PTC are reviewed and discussed.

Introduction

In endocrine surgery, controversy abounds. It is difficult, in fact, to find a topic in surgical endocrinology for which there is little or no controversy. The management of cervical nodal metastases from papillary thyroid cancer (PTC) is no exception. Fortunately, there is widespread agreement regarding the management of clinically evident nodal metastases. It seems clear, based on the risks of persistent or recurrent disease, that the optimal management is formal surgical clearance of the affected nodal basin or basins when cervical nodal metastases are clinically evident at the time of the index thyroid operation. On the other hand, because of the high frequency and uncertain clinical significance of occult nodal metastases from PTC, considerable controversy surrounds the management of the clinically negative central compartment, and the performance of so-called prophylactic central neck dissection (CND). Likewise, there is uncertainty regarding the thresholds for recommending remedial CND, given the attendant risks of the procedure and uncertain benefits. Within this contribution to the Surgical Oncology Clinics of North America , the data relevant to the surgical management of the lymph nodes of the central and lateral compartments of the neck in PTC are reviewed and discussed.

Nomenclature: prophylactic versus therapeutic

As defined in the American Thyroid Association (ATA) consensus statement on the terminology and classification of CND for thyroid cancer, a therapeutic neck dissection is one that is performed for clinically apparent nodal metastases, whether they are recognized before or during an operation, and regardless of the methodology used to detect the nodal metastases (eg, imaging, physical examination, frozen section). A prophylactic neck dissection is one that is performed on a nodal basin for which there is no clinical or imaging study evidence of nodal metastases. Prophylactic neck dissection is also synonymous with elective neck dissection.

Epidemiology of central neck metastases

Metastases from PTC are frequently found in the central compartment lymph nodes. Nodal metastases from PTC are found in the central compartment in 12% to 81% of cases, depending on the completeness of the nodal dissection by the surgeon and the level of scrutiny to identify lymph nodes by the pathologist. In surgical series of patients with PTC treated with prophylactic CND, occult positive central compartment nodes are found in at least one-third, and up to two-thirds of cases. Given the high frequency of nodal metastases in the central compartment, some experts routinely clear the central compartment in a prophylactic fashion.

Controversy regarding prophylactic central neck dissection

Routine prophylactic CND for patients with clinically node-negative PTC is controversial. The controversy is centered on the fact that there is risk associated with the performance of a prophylactic CND, and that it is unclear if there is any survival or quality-of-life benefit. Furthermore, the finding of occult nodal disease will upstage patients older than 45 and may influence the usage of radioiodine.

Given the high rate of occult nodal metastases, some experts recommend that a thyroidectomy for PTC be accompanied by at least an ipsilateral central compartment nodal dissection. Proponents of prophylactic CND argue that because of the high rate of occult central nodal metastasis, prophylactic CND should decrease the need for reoperative neck surgery by reducing locoregional recurrence and simplify follow-up by lowering postoperative serum thyroglobulin. In a study of 134 patients with PTC wherein all patients underwent a CND, the authors found that 29% of patients undergoing primary surgery for PTC had ipsilateral central neck metastases and also 29% had ipsilateral lateral neck metastases. These authors recommended routine central and ipsilateral lateral nodal compartment dissection for patients undergoing primary surgery for PTC with a T1b or larger primary tumor. Other experts cite the higher complication rate when thyroidectomy is combined with CND, with no apparent improvement in survival, as rationale against prophylactic CND. They maintain that prophylactic CND exposes patients to the additional risks of recurrent laryngeal nerve (RLN) injury and hypoparathyroidism without proven benefit.

Several recent retrospective analyses have compared outcomes of PTC patients who underwent total thyroidectomy with and without CND. In one study, 20 prophylactic CNDs were required to prevent one central compartment reoperation. A meta-analysis performed on studies that evaluated recurrence and complications associated with prophylactic CND found that the number needed to treat to prevent one recurrence was 31. Two meta-analyses have demonstrated an increased rate of transient hypocalcemia following prophylactic CND without showing a difference in permanent hypoparathyroidism or RLN injury. In most studies, prophylactic CND is associated with a higher rate of temporary hypocalcemia and parathyroid gland removal. In most formal cost-effectiveness analysis studies, prophylactic CND has not been found to be cost-effective for PTC.

The presence of nodal metastases may have a significant impact on the stage of disease based on the current American Joint Commission on Cancer (AJCC) TNM staging for thyroid cancer. Patients 45 years of age or older are upstaged to stage III for any central neck nodal metastases regardless of the size and number of metastases found. Prophylactic neck dissection is therefore likely to upstage many patients to stage III for subclinical disease. Because the AJCC staging system for differentiated thyroid cancer was not derived or validated during an era of widespread CND, it is not clear if patients upstaged for subclinical metastases found during prophylactic dissection will have the same prognosis as patients with clinically evident central neck metastases.

It is also not certain how the practice of prophylactic nodal dissection might affect the likelihood to receive therapeutic doses of radioactive iodine (RAI). Some studies indicate that patients are more likely to receive RAI after total thyroidectomy with CND. One hypothesis is that a greater frequency of detection of nodal metastases, and the associated upstaging of disease, leads to a greater utilization of RAI. Other studies show that prophylactic CND is associated with a lower probability of receiving RAI. This finding, in turn, may be due to the fact that a more complete surgical clearance of the central compartment may lead to lower preablation thyroglobulin levels, and consequently, to a lower utilization of RAI. In a study by Lang and colleagues, 51% of the patients who underwent prophylactic CND had undetectable preablative thyroglobulin.

A recent single-institution randomized controlled trial of total thyroidectomy with or without prophylactic CND in patients with PTC without evidence of preoperative or intraoperative lymph node metastases has been reported by Viola and colleagues from Pisa, Italy. Their study of 181 patients with a median follow-up of 5 years found that clinically node-negative patients treated with prophylactic CND had a reduced necessity for repeat RAI treatments compared with those patients who did not undergo CND. However, the prophylactic CND patients also had a significantly higher prevalence of permanent postoperative hypoparathyroidism (19.4 vs 8.0%).

Preoperative assessment of the cervical nodal compartments

The assessment of lymph node status before an operation for PTC is necessary because the presence and location of metastatic lymph nodes may not be clinically apparent, and the identification of nodal metastases will frequently alter the planned procedure. All patients should undergo a comprehensive history and physical examination focused on determining the extent of disease. Unfortunately, physical examination is notoriously unreliable for the exclusion of cervical nodal metastases. Imaging studies, however, can detect abnormal lymph nodes in patients who have no palpable lymphadenopathy and may also yield information that alters the extent of the operation, even when overt nodal metastases are present.

Imaging Studies

Routine preoperative sonographic imaging of the cervical nodal basins changes the extent of surgery in as many as 41% of patients. In a retrospective cohort study of 486 patients who underwent neck ultrasound before initial operation for PTC, ultrasound detected abnormal lymph nodes in 16% of patients who had nonpalpable lymph nodes on physical examination and changed the extent of surgery in 15 of 37 (41%) patients who had palpable lymph nodes on physical examination. Similarly, in a retrospective study of 151 patients who underwent neck ultrasound before initial operation for differentiated thyroid cancer, ultrasound detected abnormal lymph nodes in 52 (34%) patients who had nonpalpable lymph nodes on physical examination. Most patients with PTC who have lymph node metastases will have them in the inferior aspect of the neck. In a retrospective study of 578 lymph nodes that underwent fine needle aspiration (FNA) biopsy in 588 patients with differentiated thyroid cancer, 67% of malignant lymph nodes were found in the inferior third of the neck, whereas 46% of lymph nodes biopsied in the superior third of the neck were benign.

Multiple imaging modalities have been studied for the preoperative staging of patients with PTC. Computed tomography (CT) is the preferred imaging modality for the preoperative staging of patients with head and neck squamous cell cancers, but is not used routinely for the staging of PTC. Nonetheless, CT can characterize the size, shape, appearance, and contrast enhancement pattern of lymph nodes and may be helpful in the prognostication of cervical lymph nodes in patients with PTC. CT features of malignant lymph nodes include size greater than 1.5 cm in levels I or II, greater than 0.8 in the retropharyngeal space, and greater than 1.0 cm in other locations; spherical shape; cystic change; presence of calcifications; and abnormal contrast enhancement. In the setting of a known head and neck squamous cell cancer, CT has approximately 80% sensitivity and specificity for the detection of lymph node metastases. There is no established size criterion for metastatic lymph nodes in PTC, however, and the sensitivity of CT may be lower in patients with PTC due to the higher rates of micrometastatic disease, which may not cause a change in the appearance of these lymph nodes on CT. In large retrospective studies evaluating the accuracy of CT in detecting metastatic lymphadenopathy in patients with PTC, CT has a sensitivity of 50% to 67% and specificity of 76% to 91% for detecting metastatic lymph nodes in the central compartment of the neck. Likewise, CT has a sensitivity of 59% to 82% and a specificity of 71% to 100% for detecting metastatic lymph nodes in the lateral compartment in PTC.

The ATA guidelines on the management of thyroid cancer recommend against the routine use of preoperative imaging studies, such as CT, MRI, or PET, for the initial staging of PTC. In some cases, however, these imaging modalities may play an important role in the preoperative evaluation of the patient. CT has been the most widely studied cross-sectional imaging modality, and its main advantages are that it is not operator dependent and that it generates high-resolution images with the ability to perform multiplanar image reconstructions. Its main limitation is that the iodine load associated with the intravenous contrast given during the scan may reduce RAI uptake for several weeks after administration. CT can be particularly helpful in the evaluation and surgical planning for patients with advanced PTC, or those with large, fixed, or substernal cancers. In such cases, CT may accurately demonstrate extension of disease into the mediastinum, invasion into adjacent structures such as the aerodigestive tract, or reveal lymph node metastases in areas that are poorly assessed by ultrasound (retropharyngeal/retrotracheal space, low-level VI/superior mediastinum). MRI has not been found to be particularly helpful in the identification of cervical nodal metastases from thyroid cancer due to poor sensitivity and only moderate interobserver agreement. PET scanning is useful for imaging patients with poorly differentiated thyroid cancers, but adds little to the imaging of well-differentiated thyroid cancers.

The ATA and National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines recommend comprehensive neck ultrasound for the preoperative staging of PTC. High-resolution neck ultrasound has been reported to have sensitivity of 52% to 93% and specificity of 79% to 100% for the detection of abnormal lymph nodes in patients with PTC, in both index and reoperative settings. Sensitivities vary widely between studies, while specificities are consistently high. Sensitivity is higher for the detection of abnormal lymph nodes in the lateral compartment of the neck compared with the central compartment of the neck, as the assessment of the central neck may be affected by surrounding structures, such as the tracheal air shadow, clavicle, and sternum. Cervical sonography has several advantages over other imaging modalities. Compared with CT, ultrasound is less costly, does not expose the patient to radiation, can be performed repeatedly in children and pregnant women, is painless and noninvasive, does not require intravenous access, does not generally precipitate claustrophobic reactions, and does not have a maximum weight limit. Limitations of ultrasound include that it is operator dependent and that it may be limited in evaluating lymph nodes in patients with high body mass index or in certain locations, such as the retropharyngeal, paratracheal, or retrotracheal spaces, level VI, and the superior mediastinum.

Ultrasound can help characterize a lymph node as benign or malignant based on size, shape, and appearance. Sonographic features of benign lymph nodes include flattened elongated shape, smooth border, and hyperechoic hilum. Sonographic features of malignant lymph nodes include enlarged size, rounded shape, loss of hilar architecture, cystic change, hyperechoic punctate microcalcifications, and hypervascularity. No single sonographic feature, however, has adequate sensitivity and specificity for the detection of metastatic disease. In a prospective study of 103 suspicious lymph nodes detected on ultrasound in 18 patients who underwent operation for recurrence of differentiated thyroid cancer, Leboulleux and colleagues found that the criterion of long axis greater than 1 cm had only 68% sensitivity and 75% specificity for the detection of a lymph node metastasis. It should be noted that benign reactive lymphadenopathy is frequently encountered in the submental, submandibular, subdigastric, and high jugular regions; consequently, under normal conditions, lymph nodes in these areas may be considerably larger than lymph nodes in the remainder of the lateral neck. In Leboulleux’s study as well as another similar prospective study of 350 lymph nodes evaluated in 112 patients with PTC by Rosario and colleagues, loss of fatty hilum had 88% to 100% sensitivity and 29% to 90% specificity, and cystic appearance and hyperechoic punctate calcifications each had 100% specificity but only 11% to 20% and 46% to 50% sensitivity, respectively, for the detection of lymph node metastases.

Image-Guided Needle Biopsy

A definitive diagnosis of malignancy in a cervical lymph node is best obtained by ultrasound-guided FNA biopsy. Cytology from FNA has high sensitivity (73%–86%) and specificity (100%) for the detection of metastatic PTC, but can be limited by nondiagnostic or inadequate samples. Measurement of thyroglobulin in the FNA biopsy aspirate fluid has been developed as an adjunct to the cytologic evaluation of suspicious-appearing cervical lymph nodes. This technique is semiquantitative in that it involves rinsing the needle used for the aspirate into 1 mL of saline and assaying the thyroglobulin level in that fluid by immunoradiometric or chemiluminescent assay. Some reports describe rinsing the needle in thyroglobulin-free serum; however, a study by Frasoldati and colleagues demonstrated that using normal saline as the washout fluid yielded equivalent results. The addition of the aspirate thyroglobulin level to the cytologic assessment can improve the diagnostic sensitivity of FNA to 86% to 100%, and can be diagnostic even when the number of cells is insufficient for standard cytologic analysis. Several authors have proposed threshold values which, when exceeded, indicate metastatic thyroid cancer; however, universal agreement has not been achieved. Because it has been recognized that the aspirate thyroglobulin level is correlated to the serum TSH and serum thyroglobulin levels, it may be prudent to obtain all 3 samples in the same setting. In one report, an aspirate thyroglobulin greater than 36 ng/mL in a patient with a thyroid gland and greater than 1.7 ng/mL in a patient without a thyroid gland was defined as being indicative of metastasis. However, many studies suggest that much lower thresholds might be more sensitive. In one study, the threshold of 1.0 ng/mL was optimal for making the diagnosis of metastatic PTC with a sensitivity of 93.2% and a specificity of 95.9%. Another investigator used the same thresholds of 1 ng/mL for patients with serum thyroglobulin less than 1 ng/mL and found that the sensitivity and specificity were 93% and 100%, respectively. The same study demonstrated that an aspirate to serum thyroglobulin ratio threshold of 0.5 for patients with a serum thyroglobulin greater than 1 ng/mL had a sensitivity of 98% and specificity of 98% for the detection of metastatic PTC. In another study, an aspirate thyroglobulin threshold value of 0.2 ng/mL had a sensitivity of 100% and specificity of 87.5%.

Although approximately 25% of patients with thyroid cancer have circulating antibodies that interfere with the assays used to detect thyroglobulin, these antithyroglobulin antibodies have not been found to interfere with the detection of thyroglobulin in FNA aspirate specimens. Clearly, thyroglobulin only has utility as a tumor marker in patients with differentiated thyroid cancers of follicular cell origin. Consequently, an important limitation of this technique is in the evaluation of lymph node metastases from medullary thyroid cancer, or poorly differentiated or undifferentiated thyroid cancer. Thyroglobulin assay also has no role in the prognostication of thyroid nodules.

Implications for Surgical Planning

Systematic compartment-oriented dissection is indicated when cervical nodal metastases are identified. Formal clearance of the nodal basin has been shown to improve both recurrence rates and survival. Selective lymph node removal (“berry picking”) is not recommended, because this leaves behind lymph nodes that are at risk for developing recurrent disease, which would then be more difficult to remove in a reoperative field.

Intraoperative assessment of lymph node status

The role of prophylactic CND during thyroidectomy for PTC remains controversial. Some surgeons perform prophylactic CND routinely; some surgeons perform prophylactic CND only if there is metastatic disease in the lateral compartment, and some surgeons rely on intraoperative assessment of the lymph nodes in the central compartment and perform CND selectively. In this section, the methods of intraoperative assessment of the central and lateral compartments are described.

Intraoperative Inspection, Palpation, and Frozen Section

Many strategies exist for the intraoperative assessment of central compartment lymph nodes, including inspection and palpation and intraoperative frozen section. The accuracy of intraoperative inspection and palpation to assess the status of the central compartment lymph nodes was examined in a prospective study of 47 patients with PTC who underwent thyroidectomy with routine prophylactic CND. This study demonstrated poor sensitivity (49%–59%) and specificity (67%–83%) of inspection and palpation in identifying metastatic central neck lymph nodes regardless of level of surgeon experience (senior surgeon, fellow, or resident). Some surgeons use the results of intraoperative frozen section of a central neck lymph node to decide on the necessity or extent of formal CND. The most common lymph nodes evaluated in this manner are the prelaryngeal, precricoid, or pretracheal nodes.

The Delphian lymph node is the eponymous term for a precricoid lymph node with potential for harboring metastatic PTC. The precricoid lymph nodes have been studied as predictors of advanced disease in thyroid cancer. Although the significance of a positive node is controversial, large, retrospective studies examining this issue have found that 20% to 25% of patients with PTC who had precricoid lymph nodes examined had a positive Delphian lymph node. Furthermore, a positive Delphian lymph node was associated with larger primary tumor size, multicentric PTC, extrathyroidal extension, lymphovascular invasion, and more nodal disease. A positive Delphian node has also been found to predict additional central neck lymph node metastases with a sensitivity and specificity of 41% to 100% and 37% to 95%, respectively, and predicts lateral neck lymph node metastases with a sensitivity and specificity of 50% to 85% and 76% to 88%, respectively. Because of the relationship between the Delphian lymph node and the status of the remainder of the central compartment, some surgeons will perform a CND whenever a Delphian node is identified. Caution must be exercised in interpreting these data, however, because not all studies examining this issue performed CND routinely, and therefore, the true negative predictive value of a benign precricoid lymph node is not known.

Intraoperative Assessment of the Lateral Compartments

Although the performance of routine prophylactic CND is controversial, there is little controversy regarding prophylactic lateral compartment lymph node dissection for PTC. Prophylactic dissection of the lateral compartments is not indicated for PTC. The sensitivity and specificity of high-resolution ultrasound for the evaluation of the lateral compartment of the neck are sufficient to rule out clinically significant nodal disease in the lateral compartment, and therefore, it is not necessary to explore the lateral compartment of the neck intraoperatively if the preoperative ultrasound is normal. Lateral compartment lymph node dissection is recommended only for therapeutic purposes, such as clinically apparent or biopsy-proven lymph node metastases.

As an adjunct, some surgeons advocate intraoperative ultrasound after the completion of the lateral neck dissection to assess for residual disease. A prospective study of intraoperative ultrasound after lateral neck dissection in 25 patients with thyroid cancer (23 PTC, 2 medullary thyroid cancer) demonstrated that intraoperative ultrasound identified residual abnormal lymph nodes in 16% of patients. Moreover, a retrospective study of 101 patients with PTC showed a statistically significant difference in the rate of residual/recurrent tumor in patients who underwent surgery with or without ultrasound guidance (2 vs 12%, P <.05).

Compartmental anatomy

Definition of the Central Neck Compartment

The first broadly accepted contemporary report to attempt to standardize CND terminology was by Robbins and colleagues in 1991. In 2009, the ATA convened a multidisciplinary panel of experts and developed a consensus statement on the terminology and classification of CND for thyroid cancer. The definitions from this consensus guideline are the most widely accepted standards and will thus be referenced in the following anatomic and procedural descriptions.

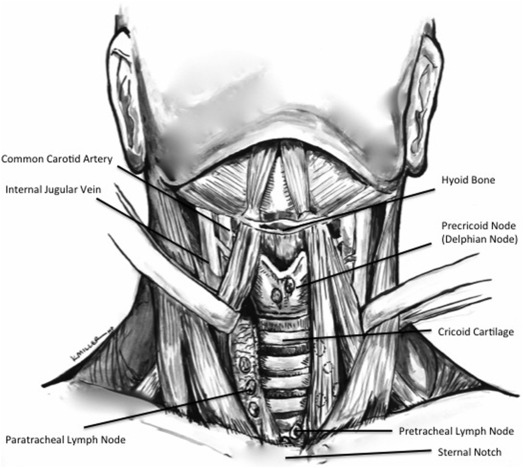

The nomenclature used to describe the neck nodal basins was originally developed by the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Head and Neck Surgery Service and modified and updated by the American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery. The neck is divided into 7 node-bearing levels, and each is referred to by Roman numeral. Six sublevels have been described and are designated by the letters A or B. The central neck compartment (also known as the anterior compartment) is designated level VI. It is bounded by the hyoid bone superiorly, the suprasternal notch inferiorly, the common carotid artery (or lateral border of the sternohyoid muscle) laterally, the deep layer of the deep cervical fascia posteriorly, and the superficial layer of the deep cervical fascia anteriorly ( Fig. 1 , Table 1 ). Included in level VI are the precricoid lymph nodes, pretracheal lymph nodes, and the paratracheal lymph nodes both anterior and posterior to the RLNs; these 3 lymph node packets are the most commonly involved central compartment lymph nodes in PTC. The ATA consensus statement on CND includes level VII in the definition of the central neck compartment, which is bounded superiorly by the suprasternal notch, and inferiorly by the innominate artery, and contains lymph nodes and thymic tissue.

| Level | Anatomic Designation | Boundaries | Sublevel Designation/Notable Contents |

|---|---|---|---|

| I | Submental (IA) | Triangular boundary from the anterior belly of the digastric muscles and hyoid bone | IA |

| Submandibular (IB) | Anterior belly of digastric muscle to stylohyoid muscle to the body of the mandible. Includes: submandibular gland | IB Marginal mandibular nerve | |

| II | Upper jugular | Upper third of the IJV and CN XI (superior) to the level of the hyoid bone (inferior), the stylohyoid muscle (anterior/medial), and the posterior border of the SCM (posterior/lateral) | IIA: LN-bearing tissue anterior (medial) to CN XI IIB: LN-bearing tissue posterior (lateral) to CN XI Marginal mandibular nerve, IJV, CN XI, phrenic nerve, vagus nerve, cervical sympathetic trunk |

| III | Middle jugular | Middle third of IJV from inferior border of hyoid bone (superior) to inferior border of cricoid cartilage (inferior), lateral border of SHM (anterior/medial), and posterior border of SCM (posterior/lateral) | IJV, CN XI, phrenic nerve, vagus nerve, cervical sympathetic trunk, brachial plexus |

| IV | Lower jugular | Lower third of IJV from inferior border of cricoid cartilage (superior) to clavicle (inferior), lateral border of SHM (anterior/medial), and posterior border of SCM (posterior/lateral) | Virchow’ node, IJV, CN XI, phrenic nerve, vagus nerve, cervical sympathetic trunk, brachial plexus, thoracic duct/right neck cervical lymphatic duct |

| V | Posterior triangle/supraclavicular | Convergence of SCM and trapezius (superior) to clavicle (inferior), posterior border of SCM (anterior/medial), anterior border of trapezius (posterior/lateral). | VA a : (superior) lymph nodes along CN XI VB a : (inferior) transverse cervical and supraclavicular lymph nodes |

| VI | Anterior (central) compartment | Hyoid bone (superior) to suprasternal notch (inferior) to common carotid arteries (lateral) | Delphian (precricoid) node, pretracheal, and paratracheal lymph nodes along the RLNs |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree