For the 20% of patients with resectable colorectal liver metastases (CRLM), hepatic resection is safe, effective and potentially curative. Factors related to the primary and metastatic tumors individually and in clinical risk-scoring schemes are the best prognostic factors, although it is difficult to define patient groups with resectable, liver-limited CRLM that should be excluded from surgery. Systemic chemotherapy for metastatic colorectal cancer has improved but does not improve overall survival as adjuvant therapy after resection. Conversion to complete resection with systemic and/or hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy is an appropriate goal for patients with unresectable CRLM.

Key points

- •

Of the 136,000 patients diagnosed with colorectal cancer, 50% will develop metastases and most of these will be liver metastases, making colorectal liver metastases (CRLM) a significant public health problem.

- •

For the 20% of patients with resectable CRLM, hepatic resection is safe and effective, with an operative mortality of 1%, overall 5-year survival of 50% to 60%, and a 20% cure rate.

- •

Factors related to primary and metastatic tumors individually and in clinical risk-scoring schemes are the best prognostic factors; however, it is difficult to define patient groups with resectable, liver-limited CRLM that should be excluded from surgery.

- •

Systemic chemotherapy for metastatic colorectal cancer has improved; however, trials of adjuvant and/or neoadjuvant therapy around the time of hepatic resection have shown improvement in progression-free survival, but not overall survival.

- •

Conversion to complete resection with systemic and/or hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy is a reasonable goal for patients with unresectable CRLM because outcomes are similar to those in patients with initially resectable disease.

Introduction, epidemiology, and natural history

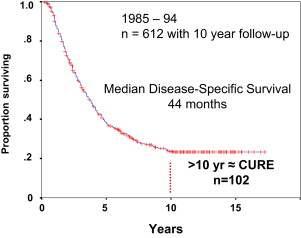

More than 90% of cancer-related mortality is due to metastatic disease and not from the primary tumors from which these arise. Death from colorectal cancer is no different and, therefore, identification of optimal diagnostic, predictive, surgical, and perioperative modalities to prevent death from colorectal liver metastases is of paramount importance. Colorectal cancer is the third most common cancer in men and the second most common in women worldwide. Approximately 96,000 patients will be diagnosed with colon cancer and 40,000 with rectal cancer in 2014 ; unfortunately, 50,000 will die of their disease. Of the 136,000 patients diagnosed with colon and rectal cancer, 50% will develop metastases and a large proportion of these will be liver metastases. Unresectable disease is the norm in these cases, but among the estimated 20% who are able to achieve complete resection there is an associated overall 5-year survival of 50% to 60%. In fact, liver resection is the only treatment associated with long-term survival in patients with colorectal liver metastases (CRLM). Furthermore, if patients are selected well, up to 20% are cured after hepatectomy for CRLM ( Fig. 1 ). This review describes the important aspects related to the surgical care of patients with CRLM.

Cattell performed what was probably the first hepatic resection for metastasis from the rectum in 1939, and reported that the patient was alive 12 months later. Early on, George Pack of Memorial Hospital in New York wrote that liver resection for CRLM was indicated when the primary tumor was controlled and a long interval had occurred between resection of the primary and discovery of the metastatic lesion. Interestingly Dr Quattlebaum, an early proponent of hepatic resection, proposed metastasectomy for “any and all” lesions unless the patient was deemed “incurable,” a proposal that is still relevant, although incompletely defined, to the present day. Review of natural history data from the comprehensive monograph Solid Liver Tumors by Foster and Berman, published in 1977, indicated that the mean survival for unresected CRLM ranged from 5 to 9 months in multiple series and that no survivors were noted at 5 years. In a series of more than 1000 patients reported in 1990, median survival was 6.9 months for unresectable CRLM and 14.9 months for resectable disease that was not resected. However, if disease was resected with negative margins, the median survival was 30 months with a 38% 5-year survival. It has become clear that without surgical management, median survival is measured in months and 5-year survival is rare. In the modern era, patients with resected CRLM now have an associated 5-year overall survival (OS) of 50% to 60% and a long-term cure rate of approximately 20% ( Table 1 ). Systemic chemotherapy for metastatic colorectal cancer has improved over the last 2 decades. Although response rates typically exceed 50% and median survival in most trials approximates 2 years, 5-year survival is uncommon and long-term cure is exceedingly rare.

| Authors, Ref. Year | N | Mortality (%) | 5-Year Survival (%) | 10-Year Survival (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hughes et al, 1986 | 607 | n/a | 33 | n/a |

| Scheele et al, 1991 | 219 | 6 | 39 | n/a |

| Gayowski et al, 1994 | 204 | 0 | 32 | n/a |

| Scheele et al, 1995 | 469 | 4 | 39 | 20 |

| Nordlinger et al, 1996 | 1568 | 2 | 28 | n/a |

| Jamison et al, 1997 | 280 | 4 | 27 | 20 |

| Fong et al, 1999 | 1001 | 3 | 37 | n/a |

| Choti et al, 2002 | 226 | 1 | 40 | n/a |

| Abdulla et al, 2004 | 190 | n/a | 58 | n/a |

| House et al, 2010 | 1600 | 8-year | ||

| Era 1: 1985–1998 | Era 1: 1037 | Era 1: 2.5 | Era 1: 37 | Era 1: 26 |

| Era 2: 1999–2004 | Era 2: 563 | Era 2: 1 | Era 2: 51 | Era 2: 37 |

Early reports on hepatic resection for CRLM were limited by small numbers, retrospective analyses, and susceptibility to selection bias. While 5-year survival was rare in patients who did not undergo surgery, it was possible that extreme selection of cases for resection resulted in higher percentages simply by altering the denominator. Silen penned this opinion eloquently in 1989. Although the long-term survival in patients who undergo surgery for CRLM could theoretically be a result of patient selection, comparison between series of chemotherapy and surgery over the last 4 decades showed that the results were so dramatically different that it became difficult to argue against a role for surgery or to have sufficient equipoise for a randomized trial. The argument for hepatic resection is further strengthened by the fact that patients are cured by surgery at a rate similar to that of some primary nonmetastatic malignancies.

Introduction, epidemiology, and natural history

More than 90% of cancer-related mortality is due to metastatic disease and not from the primary tumors from which these arise. Death from colorectal cancer is no different and, therefore, identification of optimal diagnostic, predictive, surgical, and perioperative modalities to prevent death from colorectal liver metastases is of paramount importance. Colorectal cancer is the third most common cancer in men and the second most common in women worldwide. Approximately 96,000 patients will be diagnosed with colon cancer and 40,000 with rectal cancer in 2014 ; unfortunately, 50,000 will die of their disease. Of the 136,000 patients diagnosed with colon and rectal cancer, 50% will develop metastases and a large proportion of these will be liver metastases. Unresectable disease is the norm in these cases, but among the estimated 20% who are able to achieve complete resection there is an associated overall 5-year survival of 50% to 60%. In fact, liver resection is the only treatment associated with long-term survival in patients with colorectal liver metastases (CRLM). Furthermore, if patients are selected well, up to 20% are cured after hepatectomy for CRLM ( Fig. 1 ). This review describes the important aspects related to the surgical care of patients with CRLM.

Cattell performed what was probably the first hepatic resection for metastasis from the rectum in 1939, and reported that the patient was alive 12 months later. Early on, George Pack of Memorial Hospital in New York wrote that liver resection for CRLM was indicated when the primary tumor was controlled and a long interval had occurred between resection of the primary and discovery of the metastatic lesion. Interestingly Dr Quattlebaum, an early proponent of hepatic resection, proposed metastasectomy for “any and all” lesions unless the patient was deemed “incurable,” a proposal that is still relevant, although incompletely defined, to the present day. Review of natural history data from the comprehensive monograph Solid Liver Tumors by Foster and Berman, published in 1977, indicated that the mean survival for unresected CRLM ranged from 5 to 9 months in multiple series and that no survivors were noted at 5 years. In a series of more than 1000 patients reported in 1990, median survival was 6.9 months for unresectable CRLM and 14.9 months for resectable disease that was not resected. However, if disease was resected with negative margins, the median survival was 30 months with a 38% 5-year survival. It has become clear that without surgical management, median survival is measured in months and 5-year survival is rare. In the modern era, patients with resected CRLM now have an associated 5-year overall survival (OS) of 50% to 60% and a long-term cure rate of approximately 20% ( Table 1 ). Systemic chemotherapy for metastatic colorectal cancer has improved over the last 2 decades. Although response rates typically exceed 50% and median survival in most trials approximates 2 years, 5-year survival is uncommon and long-term cure is exceedingly rare.

| Authors, Ref. Year | N | Mortality (%) | 5-Year Survival (%) | 10-Year Survival (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hughes et al, 1986 | 607 | n/a | 33 | n/a |

| Scheele et al, 1991 | 219 | 6 | 39 | n/a |

| Gayowski et al, 1994 | 204 | 0 | 32 | n/a |

| Scheele et al, 1995 | 469 | 4 | 39 | 20 |

| Nordlinger et al, 1996 | 1568 | 2 | 28 | n/a |

| Jamison et al, 1997 | 280 | 4 | 27 | 20 |

| Fong et al, 1999 | 1001 | 3 | 37 | n/a |

| Choti et al, 2002 | 226 | 1 | 40 | n/a |

| Abdulla et al, 2004 | 190 | n/a | 58 | n/a |

| House et al, 2010 | 1600 | 8-year | ||

| Era 1: 1985–1998 | Era 1: 1037 | Era 1: 2.5 | Era 1: 37 | Era 1: 26 |

| Era 2: 1999–2004 | Era 2: 563 | Era 2: 1 | Era 2: 51 | Era 2: 37 |

Early reports on hepatic resection for CRLM were limited by small numbers, retrospective analyses, and susceptibility to selection bias. While 5-year survival was rare in patients who did not undergo surgery, it was possible that extreme selection of cases for resection resulted in higher percentages simply by altering the denominator. Silen penned this opinion eloquently in 1989. Although the long-term survival in patients who undergo surgery for CRLM could theoretically be a result of patient selection, comparison between series of chemotherapy and surgery over the last 4 decades showed that the results were so dramatically different that it became difficult to argue against a role for surgery or to have sufficient equipoise for a randomized trial. The argument for hepatic resection is further strengthened by the fact that patients are cured by surgery at a rate similar to that of some primary nonmetastatic malignancies.

Workup and staging

In the modern era, most CRLM are asymptomatic and are typically diagnosed with imaging studies either at diagnosis or during follow-up after treatment of the primary tumor. For the purposes of detection and surveillance, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines recommend computed tomography (CT) scans to monitor for recurrence after resection of primary colorectal cancer, and additionally as a means of monitoring response and disease status in CRLM patients undergoing treatment. Imaging to assess for the presence of metastatic disease at the time of primary tumor diagnosis is indicated given the multiple treatment options available for patients with CRLM. At the time of diagnosis of CRLM a baseline carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) is helpful as a means of monitoring treatment response and/or recurrence. In those cases where metachronous CRLM is found, a colonoscopy within a year of the diagnosis is considered standard. For the patient found to have liver metastasis, staging consists of high-quality cross-sectional imaging of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis. In the case of an intact asymptomatic primary tumor, there is no urgency to resect the primary before addressing the metastasis. Ultrasonography, MRI, and 18 F-fluorodeoxyglucose PET/CT are options for imaging, but the current standard is high-quality multiphasic cross-sectional imaging of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis. Chest imaging is typically obtained with CT, and imaging of the abdomen and pelvis can be obtained with CT and/or MRI. CRLM lesions on CT are hypovascular and are usually visualized as hypodense lesions on the portovenous phase. MRI can be a useful adjunct for liver-specific disease to better characterize subtle disease findings, and lesion characterization when not clear on CT. MRI can be particularly helpful in a steatotic liver or for disappearing metastases after chemotherapy exposure.

Until recently, controversy existed regarding the utility of PET scanning over standard cross-sectional imaging in terms of staging patients with CRLM. In an early study of 40 patients with potentially resectable disease, findings on PET altered management of resection in 23% of the patients and influenced clinical decision making in 40% of patients. Surgery was avoided in 5 cases of extrahepatic metastatic disease, and in 3 cases PET findings led to biopsies proving unresectable liver disease. A French study published in 2005 evaluated the cost-effectiveness of PET in the management of metachronous CRLM. The study found that PET/CT was more cost-effective than CT alone, and that 6% of patients could avoid an unnecessary laparotomy. Although these results are intriguing, this model was based on retrospective data that were not validated. Recently, a randomized trial of PET/CT versus CT in patients with potentially resectable CRLM has been published. The use of PET/CT did not result in significant changes in surgical management, and there was no difference in resectability or long-term outcomes between the 2 groups. This trial provides definitive evidence that the routine use of PET does not significantly affect outcomes among patients with potentially resectable CRLM. The most recent NCCN guidelines for localized colon cancer do not recommend routine PET/CT for surveillance or for monitoring therapeutic progress for metastatic colorectal cancer. The authors believe that PET can be helpful in relatively uncommon selected situations where there are equivocal findings on CT or MRI that could significantly alter treatment.

Resectability: definitions and approaches

The definition of resectability revolves around the technical aspects of achieving an R0 margin while sparing a sufficient remnant liver in addition to tumor biology, extent of disease, and risk of recurrence. The surgeon must consider the patient’s ability to undergo the significant physiologic stress of a major operation and balance this against the likelihood of achieving an oncologic survival advantage. One should not confuse the ability to remove all CRLM with the underlying tumor biology that will determine outcome. Numerous techniques including parenchymal-sparing resections, intraoperative ablation, portal vein embolization, and 2-stage resections have improved our ability to safely remove larger burdens of disease while leaving a sufficient future liver remnant. Although resectability can easily be defined in terms of technical ability to remove tumors, the authors consider that this is not a complete definition. Technical resectability (eg, ability to remove all the tumors) should be defined separately from biological resectability (eg, ability to achieve long-term survival and/or cure).

The presence of 4 or more metastases was a contraindication to hepatectomy in the past, owing to the very poor reported 5-year survival rates. However, these studies were promulgated in times of inadequate staging, crude imaging, and ineffective chemotherapy. Cady and colleagues reported in 1992 a series of 129 patients who underwent resection for CRLM, and recommended that patients with more than 4 metastatic nodules not undergo attempted resection because of poor survival. More recently, multiple groups have shown that long-term survival is possible in patients undergoing resection of 4 or more CRLM (23%–51% 5-year survival). The limit on the number of metastatic lesions is still unclear, but one group reported that more than 8 metastatic lesions portends a particularly poor outcome. These reports on patients with 4 or more metastases also report very high recurrence rates, although cure is typically documented in approximately 5% to 10% of patients. One must consider the selection bias in these studies as a limiting factor, in addition to weighing the benefits of surgery in a fair manner knowing that hepatectomy may provide long-term survival without actually rendering a cure.

It is now well accepted that positive margins are associated with worse outcomes, but it is not always possible to predict the pathologic margin status preoperatively. Although there is some disagreement, most series show that a positive margin is associated with poor outcome and uncommon long-term survival. It should be noted that poor outcomes after a positive margin are not simply due to local recurrence at the margin. It is likely that this margin is a surrogate for particularly bad tumor biology. Most series indicate that negative margins, regardless of width, are associated with favorable outcomes. However, work by the authors’ group demonstrated that the width of the margin (>10 mm) was independently associated with outcome but that negative but close margins were still associated with favorable long-term survival. A predicted close margin should not preclude hepatic resection, as it is impossible to predict margin positivity and patients with negative but close margins still have a significant chance of cure and long-term survival. Technique of hepatic resection may affect margin status and outcome. Scheele and colleagues demonstrated that nonanatomic resection was associated with worse outcomes. DeMatteo and colleagues studied 267 CRLM patients, and determined that segmentectomy was associated with wider margins and improved survival in comparison with wedge resections. The goal of surgery should be to obtain an R0 resection, and although nonanatomic wedge resections are sometimes sufficient, wider segmental resections probably provide a better chance of surgical success.

Another difficult consideration in terms of resectability is the presence of limited and resectable extrahepatic disease (EHD). Historically the presence of EHD was a contraindication because of its associated poor survival. More modern series have demonstrated better long-term survival in patients with limited EHD. However, even in these highly selected patients the recurrence rates are high and cure is rare. Therefore, surgical treatment should be used sparingly in these patients as a general rule, but in highly selected patients; especially those who have undergone and responded to systemic chemotherapy, surgery should be considered. The role of surgery in patients with EHD is discussed later in further detail.

In summary, patients with less than 4 metastases, no EHD, and tumors amenable to an R0 resection should undergo resection both for the obvious associated survival advantage and the potential for cure. Patients with 4 or more metastases, resectable EHD, and/or the likelihood of close margins have a significantly lower chance of cure but do have an associated better survival rate than chemotherapy alone. These high-risk patients must be carefully selected for operation and counseled about the high risk of recurrence, the need for careful surveillance, and the likelihood of reintervention with chemotherapy or surgery.

Historically resectability at the time of laparotomy was a significant issue, with many patients being found to have additional disease precluding resection. The rate of unresectable disease at laparotomy has previously been reported at 15% to 70%. Recently the authors’ group sought to analyze the rate of operative resectability in a modern cohort of 455 CLM patients. Among these 455 patients, only 35 (7.7%) were found to be unresectable at surgery. The reasons for unresectability were extensive liver-only disease (n = 15), EHD (n = 17), marked hepatic toxicity (n = 1), and extensive adhesions precluding safe conduct of the operation (n = 2). Of note, 45 patients were found to have EHD and 27 of these still underwent resection. This markedly improved rate of operative resectability reflects better preoperative imaging and staging in addition to the expansion of resectability criteria to include patients with limited EHD. The only factor associated with unresectable disease was a prior history of EHD. Diagnostic laparoscopy was used sparingly in this cohort, and among the 55 patients who underwent laparoscopy only 4 patients were found to be unresectable. Therefore, diagnostic laparoscopy has a low yield and should only be used for specific imaging findings that would preclude resection if found to be disease at surgery. Overall, the rate of operative resectability is high, and small minorities of patients undergo nontherapeutic laparotomy.

A significant operative hurdle exists among patients with synchronous resectable liver metastases with an intact primary tumor. Synchronous liver metastases are common, occurring in 25% of patients with colorectal cancer. Three surgical approaches can be taken for these patients. A simultaneous approach combines the liver and colorectal operation into one operation. A staged approach with separate operations for the colorectal tumor and the liver was historically favored, and typically addressed the colorectal tumor first for fear of obstruction or bleeding. A more recent description of this staged approach involves liver resection first. Candidates for a liver-first approach need to have asymptomatic primaries and often have CRLM that require a major hepatectomy. A liver-first approach has also been used in patients with rectal primaries to allow for time to treat the rectal tumor with preoperative chemoradiation. Several retrospective comparisons of the 3 approaches have been published. Most show no significant differences in outcome, and some favor the simultaneous approach in terms of improved postoperative morbidity and decreased length of stay. These studies, however, are significantly biased in that the staged resections more often are in patients requiring a major hepatectomy and/or a complex rectal operation. Some studies have reported that major hepatectomy is associated with high mortality with the simultaneous approach ; however, most studies show that major hepatic resections can be safely carried out with a concomitant colorectal resection. In the management of the patient with synchronous CRLM, early involvement of a hepatic surgeon is critical for treatment planning and success. In general, the authors advocate a simultaneous approach ; however, the controversy lies in those patients who may require an extensive rectal resection and a major hepatectomy, and it is certainly reasonable to consider a staged approach in such patients.

Prognostic factors

Only decades ago, prognosis was uniformly poor for patients with unresected CRLM. Approximately 70% of patients with unresected CRLM died within 1 year, and survival beyond 5 years was rare. Looking broadly across the CRLM population in 2 large academic centers in the United States encompassing 2470 patients, Kopetz and colleagues demonstrated no significant difference in median OS for those diagnosed between 1990 and 1997, whereas significant improvements were noted in the groups diagnosed between 1998 and 2000 (18 months) and from 2004 to 2006 (29.2 months). The investigators attributed these improved survival rates to the more frequent adoption of hepatic resection and improved chemotherapeutic options. In a recent study from the authors’ group, differences in long-term outcomes were analyzed in 1600 patients who underwent resection of CRLM in 2 eras: 1985 to 1998 (n = 1037) and 1999 to 2004 (n = 563). One important finding of this study was that operative mortality was significantly less in the modern era (1% vs 2.5%). Furthermore, despite relatively worse biological characteristics, median survival improved from 43 to 64 months. These data suggest that the survival rate for CRLM has improved over time, which likely reflects better patient selection, appropriate chemotherapeutic choices, and better operative management.

Over the last few decades many retrospective case series of patients undergoing hepatic resection for CRLM have reported on individual predictors of survival. The most common predictors of shorter survival were increasing size and number of tumors, shorter disease-free interval, node-positive primary tumor, positive margins, and the presence of EHD. These individual prognostic factors, however, vary from study to study in their association with outcomes, and have not been consistent across studies. In 1999, in an attempt to improve prognostication, a Clinical Risk Score (CRS) that predicts survival after hepatic resection for CRLM was developed by Fong and colleagues using data from 1001 patients treated from 1985 to 1998 at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC). The 5 preoperative factors found to be independent predictors of poor outcomes were node-positive primary, disease-free interval less than 12 months, more than 1 tumor, largest tumor greater than 5 cm, and CEA greater than 200 ng/mL. The CRS is constructed by adding a point for each of the 5 factors, and this score correlated well with outcomes. Interestingly neither the CRS nor other individual factors precluded the possibility of cure. In the authors’ published series, the only factor that did preclude cure was a positive margin. Whereas the CRS remains a useful prognostic tool in the authors’ hands, it has not translated well across all institutions. Specifically, Zakaria and colleagues showed that the CRS had limited prognostic value in their cohort from the Mayo Clinic. Furthermore, these prognostic factors, including the CRS, do not necessarily exclude patients from resection given the possibility of long-term survival, even with poor prognostic factors limiting the clinical applicability.

Other prognostic tools have been developed to help predict outcome among patients undergoing hepatic resection for CRLM. Using 1477 CRLM patients from 1986 to 1999, a nomogram was developed incorporating several of the CRS elements, resection characteristics, and colon or rectal origin to predict 96-month disease-specific survival. Importantly this nomogram was validated in an external data set. In other work, a Japanese group developed both a preoperative and postoperative nomogram in 578 CRLM patients to predict 5-year disease-specific survival (DSS) using 6 clinical variables. Nomograms are potentially useful tools because they are dynamic, can adapt readily to clinical, pathologic, and genomic information, and provide a more precise assessment of individual risk. However, nomograms are susceptible to selection bias, can vary by institution, and often are not useful in making clinical decisions. The biggest issue among nomograms and risk-scoring systems is that it is often difficult to define groups with such a poor outcome that surgery is not advised, limiting their clinical applicability. The authors’ group has recently used the CRS and gene-expression data to better determine risk in patients with CRLM. Tumor tissue from 96 patients who underwent R0 resection were used to develop a gene-expression profile associated with outcomes. A Molecular Risk Score (MRS) was constructed and then evaluated in a test set. The MRS predicted survival independently of the CRS and, when combined with the CRS, allowed powerful prediction of outcomes ( Fig. 2 ). It remains to be seen whether the MRS can be validated in an external data set to better delineate risk allocation in CRLM patients.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree