The surgical management of primary cutaneous melanoma, from the diagnostic biopsy through the wide local excision and nodal staging, must be carefully planned, and the biology of the melanoma, microstaging and primary tumor pathologic features of the melanoma, location on the body, patient preferences, and comorbidities must be considered. The treating surgeon must balance preservation of oncologic principles, with optimization of functional and aesthetic outcome. This article reviews the rationale behind the surgical approach in the patient with a primary melanoma.

The incidence of melanoma is increasing throughout the world. This trend is mainly driven by the increased diagnosis of thin melanomas (<1 mm). Surgical excision remains the primary treatment of biopsy-proven invasive melanoma at any site. Despite recent advances and considerable enthusiasm about novel systemic treatment approaches, such as PLX4032 (a specific inhibitor targeting the BRAF V600E mutation) and ipilimumab (an antibody-mediating costimulatory blockade), that exploit our better understanding of the molecular biology of melanoma and immunobiology in general, only a small proportion of patients have a durable complete response to systemic treatment of advanced disease. Therefore, early diagnosis and adequate surgical management provide the best prospect for cure from this aggressive tumor. The initial biopsy plays a critical role in the diagnosis and selection of the appropriate surgical strategy, including the determination of optimal surgical resection margins and the decision whether or not to perform sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB). These decisions are largely based on the thickness, ulceration status, and mitotic rate of the primary melanoma. Radiological imaging with chest radiography, computed tomography, or positron emission tomography are commonly used by clinicians for initial staging after the diagnosis of intermediately thick or thick melanomas, despite a lack of consensus about its usefulness. This article focuses on the recommendations for the surgical management of primary melanoma, including biopsy techniques, selection of appropriate wide excision margins, SLNB, and surgical considerations for melanomas arising at specific sites.

Biopsy techniques

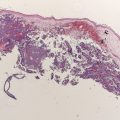

An excisional biopsy is the preferred method to establish a definitive diagnosis of melanoma and to obtain appropriate microstaging when a lesion is suspected to be a melanoma based on clinical appearance or history. The excision should be performed with narrow margins around the visible lesion and with a cuff of subdermal fat. Local anesthesia is usually sufficient for most excisional biopsies. This type of biopsy allows the dermatopathologist to review a specimen that represents the full thickness of the melanoma and to evaluate for residual tumor at the excision margins. In general, the orientation of the surgical excision should be guided by the lymphatic drainage of the surrounding skin and by the ability to optimize primary closure. On an extremity, the biopsy should typically be oriented parallel to the long axis of the extremity.

In some cases, an incisional biopsy is the only appropriate option. An example is when the patient presents with a large cutaneous melanoma, particularly in an anatomically and cosmetically difficult area such as the face. It may also be difficult to perform excisional biopsies on acral or mucosal sites. The limitations for histopathologic review of incisional biopsies are severalfold: (1) the biopsy specimen might not represent the full thickness of the melanoma (2) the number of mitoses may not be adequately assessed if the tumor is not available in its entirety and (3) the margins (both deep and lateral) may not be adequately assessed. Any limitation to the dermatopathologic review may affect both staging and the determination of optimal surgical management.

Shave biopsies are not recommended when the diagnosis of melanoma is suspected because these biopsies may limit the amount of specimen available for adequate pathologic assessment and adequate microstaging, especially the assessment of tumor thickness.

Histopathologic evaluation

Essential components of primary tumor histopathologic evaluation include the Breslow thickness (in millimeters), presence or absence of ulceration, mitotic rate, Clark level of invasion, status of lateral and deep margins, and presence or absence of satellite lesions. Other features, such as the presence and extent of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes, regression, angiolymphatic invasion, neurotropism, and histologic subtype, may also provide useful additional information.

Histopathologic evaluation

Essential components of primary tumor histopathologic evaluation include the Breslow thickness (in millimeters), presence or absence of ulceration, mitotic rate, Clark level of invasion, status of lateral and deep margins, and presence or absence of satellite lesions. Other features, such as the presence and extent of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes, regression, angiolymphatic invasion, neurotropism, and histologic subtype, may also provide useful additional information.

Wide local excision: determination of appropriate resection margins for primary melanoma

Overview and Historical Perspective

Wide local excision (WLE) of the primary melanoma and the surrounding tissue is a critical part of potential curative therapy for melanoma. The surgical treatment approach has evolved considerably over the last several decades. One important element of the surgical excision is the extent of the margins, an issue that has been studied extensively over the last 4 decades. Until the 1970s, 3- to 5-cm margins were often recommended, without distinction by thickness of the tumor. The routine use of such wide margins of resection frequently necessitated skin grafting to cover the defect and increased the morbidity of the resection. More than 100 years ago, Handley published his treatment of locally advanced cutaneous melanoma with wide (up to 5 cm) margin excision, and the exclusive use of wide margin resection for all melanomas has been routinely, although not necessarily correctly, attributed to him. Decades later, pathologic findings of atypical melanocytes present at the periphery of melanomas, several centimeters away from the primary tumor, added to the belief that a minimum of 5-cm margin of excision was mandatory for adequate surgical treatment of melanoma.

The indiscriminant use of wide resection margins for all melanomas was called into question starting in the late 1970s, when evidence emerged that narrower resection margins were associated with identical outcomes in patients with melanoma. Because of the retrospective nature and the limited numbers of patients, the issue remained controversial for more than a decade until large, randomized, prospective studies investigating the issue were completed. In the following section, evidence-based recommendations for primary melanoma resection margins are discussed.

Key Clinical Trials Assessing Surgical Resection Margins

In 1988, a randomized prospective trial by the World Health Organization (WHO) Melanoma Programme in which more than 600 patients with melanoma thickness less than or equal to 2 mm were randomized to resection with 1-cm versus 3-cm margins revealed no differences in the incidence of lymph node or distant metastases, disease-free survival (DFS), or overall survival (OS) between the 2 groups at a median follow-up of 90 months ( Table 1 ). A subgroup analysis of recurrence-free survival or OS in patients with a primary tumor thickness of 0.1 to 1.0 mm versus 1.1 to 2.0 mm revealed no difference between the groups. However, in the group that had a tumor thickness of 1.1 to 2.0 mm, there was a nonsignificant increase in local recurrences in those who underwent a 1-cm margin (n = 3) resection compared with those who underwent a 3-cm margin (n = 0) resection. Therefore, although the investigators felt that a 1-cm margin of excision was appropriate for melanomas less than 2 mm in thickness, others cited the local recurrence data to support their determination that a 1-cm margin was safe only for patients with a melanoma of up to 1 mm in thickness.

| Trial | Number of Patients | Breslow Thickness | Margins Compared (cm) | Percentage of OS for Narrow Margin/Wide Margin | Percentage of Nodal Metastases for Narrow Margin/Wide Margin | Percentage of Distant Metastases for Narrow Margin/Wide Margin | Comment | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WHO Melanoma Trial | 612 | <2 mm | 1 vs 3 | 89.6%/90.3% (8 y) | NR | NR | 4 local recurrences in narrow-margin group only | |

| Swedish Melanoma Study Group | 989 | >0.8 mm to ≤2 mm | 2 vs 5 | 79%/76% (11 y) | 15%/12% (8 y) | 15%/14% (8 y) | — | |

| French Cooperative Group Trial | 336 | ≤2.0 mm | 2 vs 5 | 87%/86% (10 y) | 8.1%/6.7% (20 y) | 2.5%/6.1% (20 y) | — | |

| Intergroup Melanoma Trial | 486 | 1–4 mm | 2 vs 4 | 70%/77% (10 y) | 2.1%/2.6% (local recurrence) | NR | Included nonrandomized group with head and neck or distal extremity melanomas receiving 2-cm margins, which had higher local recurrence rate (6.3%) | |

| United Kingdom Melanoma Trial | 900 | >2 mm | 1 vs 3 | NR; HR, 1.07 (95% CI, 0.85–1.36); P = .6 (5 y) | 33%/29% (5 y) | NR | No surgical nodal staging done |

More than a decade later, the results of the WHO trial were confirmed by 2 large, randomized, prospective, multicenter European clinical trials. The Swedish Melanoma Study Group performed a phase 3 trial in which almost 1000 patients with a primary melanoma of the trunk or the extremities with a thickness greater than 0.8 mm and less than or equal to 2.0 mm were randomized to receive WLE with margins of either 2 or 5 cm. No difference in OS was found at a median follow-up of 11 years. The local recurrence rate was low and was not increased in patients with resection margins of 2 cm after a median follow-up of 8 years. The French Cooperative Group conducted a phase 3 trial in which 337 patients with melanoma thickness less than or equal to 2 mm were enrolled over a period of 5 years at 9 European institutions. Patients were randomized to undergo WLE with resection margins of either 2 or 5 cm, which were identical to the margins in the Swedish trial. The investigators concluded that the 10-year OS and local recurrence rates were not statistically different and that a surgical margin of 2 cm was sufficient for melanomas with thickness less than or equal to 2 mm.

Based on these trials, for melanomas with thickness less than 1 mm, resection margins should be 1 cm. However, for melanomas with thickness between 1 and 2 mm the recommendations are less clear. Based on the 3 randomized prospective trials discussed earlier, which collectively enrolled almost 2000 patients, a 2-cm resection margin is clearly sufficient for melanomas with thickness between 1 and 2 mm. However, the data from the WHO trial suggest that a 1-cm margin may be appropriate. Therefore, in general, a melanoma with thickness between 1 and 2 mm should be resected with radial margins between 1 and 2 cm. The decision whether to perform a 1- or 2-cm margin should be personalized taking into consideration primary tumor factors, patient factors, and the location of the melanoma, especially when it is located in anatomic areas where cosmetic deficits or functional problems are anticipated with wider margins, such as the face or distal extremities (fingers or weight-bearing portion of the foot). Primary tumor ulceration status was not comprehensively assessed in these trials but was balanced in the subgroup of patients for which data were available in the French trial.

A multi-institutional and international cooperative group trial (The Intergroup Melanoma Trial) was conducted to assess surgical resection margins for melanomas with intermediate thickness (1–4 mm). About 486 patients with trunk and proximal extremity melanomas were randomly assigned to receive either a 2-cm or 4-cm surgical resection margin around the melanoma biopsy site. The local recurrence rate was 2.1% for 2-cm margins and 2.6% for 4-cm margins ( P = .72). There use of skin grafts for wound closure in the group with 4-cm margins (46%) was significantly higher than that in those with 2-cm (11%) margins. Furthermore, 10-year OS rates (70% vs 77%) were not affected by the smaller resection margins. The investigators concluded that 2-cm resection margins are appropriate for melanomas with a thickness of 1 to 4 mm.

The United Kingdom Melanoma Study Group assessed the effect of a 1-cm versus 3-cm excision margin in patients with high-risk cutaneous melanomas (>2 mm Breslow thickness) on the trunk or limbs in a multicenter, randomized, prospective trial, enrolling 900 patients. None of these patients underwent any surgical staging procedure of the regional lymph node basins, including SLNB or elective lymph node dissection (ELND). Locoregional (local, in-transit, and nodal) recurrence was significantly more frequent in the group with 1-cm resection margins than in the group with 3-cm resection margins (168 vs 142, respectively, P <.05), whereas OS ( P = .06) was similar in both groups. The investigators recommend that a surgical margin of 1 cm should be avoided in patients with melanoma thicker than 2 mm because of the significantly higher risk of locoregional recurrence in this group.

However, there are several considerations to take into account when considering this trial. Nodal failures accounted for the largest number of locoregional recurrences, with no significant differences between the 2 groups when only local and in-transit recurrences were addressed (nodal failure excluded from locoregional failure analysis and considered separately). It is possible that a 3-cm margin excises clinically significant microscopic disease that would eventually manifest as a locoregional recurrence if a smaller 1-cm margin of resection is performed. It is also possible that SLNB or ELND would have removed microscopic disease that would have ultimately progressed to a locoregional failure (especially considering the high nodal recurrence rate). However, because no nodal staging surgery was performed, the effect is unclear. Considering current practice for patients with primary melanomas thicker than 2 mm and clinically uninvolved nodes, SLNB would be offered to most of the patients in this trial. The difference in locoregional failure rates between the 2 groups did not translate into a difference in the OS. Although it is possible that this observation can be explained by too few locoregional failures to statistically affect OS, another possibility is that locoregional failure is not necessarily a precursor to distant disease.

Another trial from the Scandinavian group randomized 936 patients with melanomas with thickness greater than 2 mm to receive resection margins of 2 cm and 4 cm and reported no differences in local recurrence rate, DFS, or OS after 5 years of follow-up. One retrospective study from The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center assessed clinical outcome in 278 patients with melanomas thicker than 4 mm who had resection margins either smaller or larger than 2 cm. Of the melanomas evaluated, 60% were between 4.1 and 6.0 mm in thickness, while 68% of patients had ulcerated lesions and 28% had lymph node disease. Margins less than 2 cm were performed in 63% of patients, and 37% had margins larger than 2 cm. No differences in local recurrence rate or OS at 5 or 10 years were found and the investigators concluded that a 2-cm resection margin may be applied to this group of patients who were at high-risk for melanoma.

Resection Margins: Meta-Analysis and Recommendations

The earlier-mentioned randomized trials, including the WHO Trial, the Intergroup Melanoma Trial, the Swedish Melanoma Study Group Trial, the United Kingdom Melanoma Study Group trial, and the French Cooperative Group, were assessed in a meta-analysis. A total of 3313 participants, 1639 randomized to narrow excision margins (1–2 cm) and 1674 to wide excision margins (3–5 cm), were included. Overall there were 393 deaths in the groups with narrow excision margins and 403 in the groups with wide excision margins. The pooled odds ratio for death was 0.99 (95% confidence interval, 0.85–1.17; P = .93), and the investigators concluded that wide (3–5 cm) excision margins do not improve the overall mortality compared with narrow margins in the surgical treatment of primary cutaneous melanoma.

Based on the current evidence, the authors recommend that excision margins for melanomas with thickness less than 1 mm should be 1 cm. For melanomas with thickness between 1 and 2 mm, the recommendations are somewhat less clear; most guidelines advise margins between 1 and 2 cm. For melanomas with thickness greater than 2 mm, excision margins of 2 cm are appropriate ( Table 2 ). It is recommended that the excision extends down to the muscular fascia. Deeper resections that include fascia have not improved outcomes. Prospective randomized data are not available for margin recommendations in the case of melanomas in situ. In general, based on consensus panels, a 0.5- to 1.0-cm radial margin with a deep extension that includes subcutaneous fat is suggested.

| Breslow Thickness | Recommended Resection Margins (cm) | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| Melanoma in situ | 0.5–1.0 cm | — |

| <1 mm | 1 cm | — |

| 1–2 mm | Between 1 and 2 cm | Recommended by most guidelines |

| >2 mm | 2 cm | — |

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines recommend a 0.5-cm margin for melanomas in situ, 1 cm margins for melanomas with thickness less than or equal to 1 mm, 1- to 2-cm margins for melanomas with thickness between 1.01 and 2.00 mm, and 2-cm margins for melanomas with thickness greater than 2 mm ( http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/f_guidelines.asp ). The clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of melanomas in Australia and New Zealand recommend a 0.5-cm margin for melanoma in situ, a 1-cm margin for melanomas with thickness lesser than 1 mm, 1- to 2-cm margins for melanomas with thickness between 1 and 4 mm, and a 2-cm margin for melanomas with thickness greater than 4 mm ( http://www.nhmrc.gov.au/publications/synopses/cp111syn.htm ).

Surgical management

Approach to WLE

A WLE is the standard therapeutic intervention used to address the primary melanoma site. The WLE is intended to remove the entire primary melanoma along with any microscopic melanoma cells that may be present in the adjacent tissue. However, in addition to these oncologic principles, the surgeon must consider the morbidity of the resection and its effect on both function and cosmetic outcome. The radial margin chosen for the WLE is determined by the Breslow thickness as described earlier. When all or part of the primary melanoma remains intact, the margin should be measured from the perimeter of the visible lesion. When the primary melanoma has been excised during the biopsy, the margin is measured from the periphery of the biopsy scar. The resulting defect is greater for a shave biopsy scar than for an usually linear scar after excisional biopsy. For most invasive melanomas, a full-thickness excision of skin and subcutaneous tissue is removed down to, but not including, the muscular fascia. Thus, the depth of excision may be variable depending on the location of the primary tumor. From the patient’s perspective, the length of the WLE scar can be longer than what they may have anticipated, and the authors, therefore, routinely draw out the proposed surgical excision and estimated scar length to better prepare the patient for surgery during preoperative assessment and consultation.

The planning of the surgical incision needs to take into consideration not only the required margin of excision but also the anatomic location of the melanoma and the nature of the local tissue. When the surgeon measures a 1- or 2-cm margin from the primary melanoma or biopsy site, an oval or circular defect is typically marked out for excision. However, for improved cosmetic outcome and when primary closure is planned, the defect is modified into an ellipse. This modification allows for a more gradual transition in wound contour and decreases the size of the “dog-ears” that persist at the poles of the incision. Although the ellipse is often described as requiring a length 3 to 4 times that of the width of the defect, a shorter excision may be cosmetically acceptable while decreasing morbidity.

Most 1-cm margin excisions and many 2-cm margin excisions can be excised and primarily closed using an elliptical excision. On the extremities, the ellipse is oriented parallel to the long axis of the limb (just as when planning an excisional biopsy). This orientation facilitates primary closure, maximizes excision of lymphatics that are at risk for tumor cell emboli, and may decrease subsequent lymphedema risk ( Fig. 1 ). On the trunk, the incision should be oriented in a way that optimizes primary closure while ideally incorporating at-risk lymphatic tissue. At times, a modified ellipse may be necessary using a “hurricane” or “lazy S” incision.

The specimen should always be carefully oriented for the pathologist before being completely removed from the intact tissues. It is common, especially for 2-cm margins, to require the mobilization of full-thickness advancement flaps. Flaps are typically made above the level of the fascia with full-thickness advancement of tissue over the surgical defect. Closed-suction drainage may be used at the discretion of the surgeon if large flaps are made but are generally not required for most WLE reconstructions. Usually the complex closure involves 1 or 2 layers of deep absorbable sutures. Intradermal sutures placed in a buried fashion are typically used, but a deeper subcutaneous layer may also be reapproximated, at the surgeon’s discretion, if tissue of appropriate strength is available. The skin closure may be accomplished in a variety of ways depending on tension, location, mobility of the area, and surgeon preference. A subcuticular closure may be accomplished using absorbable suture or a nonabsorbable pull through suture. Interrupted nonabsorbable sutures and skin staples may also be used. Dermal adhesives or adhesive bands may also be used at the surgeon’s discretion.

It is not always possible to primarily close a WLE defect, especially on the distal extremities and in the head and neck region. Consideration, in these cases, must be given to either a skin graft or local flap technique. Skin grafts are relatively straightforward and allow for the careful monitoring of the primary excision site in patients with locally advanced melanomas. However, skin grafts have the potential for more significant morbidity, are considered more disfiguring, are insensate, and provide less protection to the underlying tissues. Split-thickness skin grafts are generally harvested from the posterior thigh. For a lower-extremity primary melanoma excision requiring a split-thickness skin graft, the graft is harvested from a donor site on the contralateral leg. Full-thickness skin grafts may be harvested from the inguinal groin crease, the lower neck region over the area of the clavicle, and behind the ear, depending on the ability to match color and texture of the skin. Full-thickness skin is harvested, and the donor site is closed primarily with dermal and subcuticular sutures. The decision to perform a skin graft or a local or rotational flap, however, must take numerous factors into account, including the location of the defect, stage of the primary melanoma, and patient comorbidities and preferences.

SLNB

The most important prognostic factor for the OS of patients with the American Joint Committee on Cancer stage I and II melanoma is the involvement of regional lymph nodes. SLNB, initially described by Morton and colleagues in 1992, is now widely performed for the initial staging of melanoma and can accurately define the stage of the regional lymph node basin in approximately 97% of patients. This technique is generally used for melanomas with thickness greater than or equal to 1 mm and has replaced ELND, which was previously a standard practice when nodes were clinically negative. The use of ELND, however, remained controversial because only 15% to 20% of patients have been shown to harbor metastatic disease in clinically negative nodes. Therefore, most patients who underwent ELND would not benefit from the surgery, which can cause debilitating postoperative lymphedema of the extremities. Furthermore, randomized trials demonstrated no benefit in OS from this procedure when all patients were considered.

SLNB may also be used in thin melanomas (<1 mm thick). Although the likelihood of melanoma metastases in the sentinel node is less than 5% for melanomas with thickness lesser than or equal to 1 mm, the use of SLNB has been proposed by some investigators, especially when adverse primary pathologic features are present, including mitotic rate greater than zero, the presence of ulceration, shave biopsy to the base of the specimen, the presence of a vertical growth phase, and for melanomas with thickness greater than 0.75 mm. Lymphoscintigraphy and intraoperative lymphatic mapping are standard elements of SLNB because lymphatic drainage cannot be predicted accurately by anatomy alone. Intradermal injection of 99m Tc-labelled colloid around the primary melanoma or excisional biopsy site allows the localization of lymph node basins and assessment of the number of draining lymph node basins and potential sentinel nodes. Other tracers are available and used in other countries. The detection rate of the sentinel lymph node by SLNB is improved with the use of vital dye in addition to the radiolabeled tracer, but dye is often not used in the head and neck area because of the risk of leaving a permanent tattoo in an exposed area. Although beyond the scope of this article, the pathologic analysis of the sentinel lymph node and the role of completion lymph node dissection (CLND) in patients with a positive sentinel node are discussed elsewhere in this issue (see the articles Pathologic Evaluation by Scolyer and colleagues and Sentinel Node Biopsy by Ross and colleagues elsewhere in this issue).

Recent attention has also focused on the use of ultrasonography (US) in combination with fine-needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) for the monitoring of regional lymph nodes and detection of metastases earlier than clinical examination only. In some centers, this technique has been reported to be associated with a high sensitivity and specificity in the follow-up of patients with melanoma. Recent studies have shown that this technology might also be useful in the initial staging of melanoma. In a report from Germany, 65% of patients with positive sentinel lymph node metastases were detected using US and FNAC and patients could directly proceed to CLND in which the sentinel lymph node examined by fine-needle aspiration was histologically assessed as the gold standard. Nevertheless, other groups have reported that US is not a substitute for SLNB and, although the technique has been incorporated in the initial staging of melanoma at some centers, it has not replaced SLNB as the standard of care.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree