Jugdeep Kaur Dhesi, Judith Partridge In recent years, there has been a growing recognition of the role for geriatric medicine specialists in the care of older surgical patients.1–4 This has been fueled in part by the increasing numbers of older people undergoing elective and emergency surgery and in part by the increasing medical complexity of older surgical patients. The increase in numbers is due to changing global demographics, resulting in an age-related increase in the prevalence of degenerative and neoplastic pathology, for which surgery is often the best treatment option, and to advances in surgical and anesthetic technique. Furthermore, patient expectations and health care professional attitudes and behaviors have evolved, with impetus provided by legislation against age discrimination. The overall impact is that rates of surgical procedures in older adults are now significantly higher than in any other age group.5,6 Although rates of surgery in the older population have increased, they have not kept pace with the observed prevalence of conditions requiring surgery. It appears that surgery may still not be offered to older patients where it would be offered to younger patients, either for symptomatic or curative benefit. For example, the rates of hip arthroplasty decline steadily beyond the age of 70 years, as do resection rates for curable cancer across a range of tumor sites.1 This is despite the fact that older adults have much to gain from surgery for symptomatic control (as in joint replacement surgery) and improved survival (as in colorectal cancer). The apparently limited access to surgery seen in some older adults may occur for a number of different reasons, but a likely contributor is the complex analysis of risk or harm versus benefit of surgery in older adults. It requires an understanding of not only the surgical and anesthetic issues, but also of life expectancy with and without surgery, alternative treatment options, modifiable risk factors, and management of predictable and unpredictable postoperative complications. Such analysis needs to be presented in a manner appropriate to the patient to facilitate shared decision making. The complexity of the older surgical population, which makes the assessment of the risk-to-benefit ratio difficult, relates to the association of aging with physiologic decline, multimorbidity, and frailty, all of which are independent predictors of adverse postoperative outcome.7 With such a profile, it is no surprise that in comparison to the younger population, older patients suffer from higher rates of postoperative morbidity and mortality when undergoing emergency and elective surgery across various surgical subspecialties.8,9 Furthermore, in older adults, a surgical procedure with associated hospitalization is more likely to result in impaired functional recovery, with a consequent need for rehabilitation, complicated hospital discharge, and increased home care or new institutionalization.10,11 This complexity in older surgical patients presents challenges throughout the surgical pathway, from the preoperative decision making phase to medical management in the postoperative period. It is increasingly apparent from recent reports and research that to achieve quality care for the older patient throughout the surgical pathway, collaboration among surgeons, anesthetists, and geriatricians is necessary.1,2,12 For these reasons, the geriatrician should be equipped with a basic understanding of the issues presented in this chapter. When considering the older surgical patient known to be at risk of an adverse postoperative outcome, the following issues are relevant. Surgery results in a stress response and increased metabolic requirements, often compounded by a catabolic state secondary to the malignancy or inflammation that necessitated the surgery. Withstanding this surgical insult requires adequate physiologic or functional reserve (capacity).13,14 Unsurprisingly, poor cardiorespiratory reserve is an established predictor of postoperative morbidity and mortality.15 Because aging, even in the absence of pathology, is associated with a decline in the physiologic reserve of all major organs, particularly cardiorespiratory reserve, evaluation and, where possible, optimization of reserve are essential. The principal purpose of assessing preoperative exercise capacity is to anticipate whether the patient will be able to increase oxygen delivery during the perioperative period. Traditionally, cardiorespiratory reserve has been described by asking patients about their exercise tolerance. An attempt has been made to formalize this assessment by considering metabolic equivalents (METs). The MET is a unit used to estimate the amount of oxygen used by the body during physical activity. One MET is the basal metabolic rate of a 40-year-old, 70-kg man at rest, which equates to 3.5 mL/kg/min. METs can be measured objectively using exercise testing but are more often described subjectively by estimating the ability to perform activities of daily living (ADLs). Poor physiologic reserve is defined as a MET less than 4 (unable to climb one flight of stairs). Limitations of such an approach include the lack of reliability in self-reporting ADLs, lack of additional value (when combined with age and ASA) in predicting outcome, and limited evidence of validity in specialties other than cardiothoracic surgery. Furthermore, METs may lack discriminatory power in older adults with other noncardiorespiratory reasons for the inability to complete ADLs, such as osteoarthritis.16 More recently, objective testing of reserve has been used in clinical practice using techniques such as the 6-minute shuttle walk, gait speed, or cardiopulmonary exercise testing (CPET). As with estimation of METS, the shuttle walk and gait speed can equally be affected by noncardiorespiratory pathology or general deconditioning. In contrast, CPET provides information on cardiorespiratory fitness. It allows measurement of oxygen uptake and carbon dioxide production while the patient exercises (using feet or hands) on a cycle ergometer attached to 12-lead electrocardiography. Various parameters can be measured, but the most frequently described is the anaerobic threshold (AT), the threshold at which aerobic metabolism switches to anaerobic. Evidence suggests that measurement of the AT can help triage patients as high or intermediate perioperative risk. Studies have used this description of risk to allocate postoperative level 2 and 3 care beds with the aim of reducing postoperative morbidity and mortality.17 Concerns regarding the use CPET include the inability of older adults to complete the test due to noncardiorespiratory issues (e.g., fatigue, motivation, joint disease), need for skilled interpretation of data, extrapolation of evidence from colorectal and vascular surgery to other surgical populations, and potential exclusion of older adults from surgical intervention on the basis of a CPET test result.18 The presence of coexisting disease—in particular anemia, diabetes, and cardiac, respiratory, and renal disease—increases the risk of adverse postoperative outcome. Although each individual condition increases this risk, a combination of more than three coexisting conditions (multimorbidity) is highly predictive of postoperative complications, poor functional outcome, and mortality.19 Because increasing age is associated with multimorbidity, with more than 40% of community-dwelling people older than 70 years living with multimorbidity,7 older adults presenting for surgery are a vulnerable population. Various scores are available to describe and measure comorbidities (e.g., the Charlson Comorbidity Index). These are useful for comparison between patient groups and stratification of risk and thus for coding and research, but their clinical utility in the surgical population is limited. Furthermore, the severity of the coexisting condition and its related complications is more important in affecting outcome than merely its presence. For example, poorly controlled diabetes associated with untreated diastolic heart failure is of more significance than well-controlled diabetes and mild optimized chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), despite the fact that the comorbidity count would be the same. Recognition of the impact of comorbidity on postoperative outcome has led to the publication of resources to guide perioperative assessment and optimization of specific comorbidities. These resources include guidelines covering cardiac disease (e.g., coronary artery disease, valve disease, cardiac failure), anemia, and diabetes (Table 37-1). Interestingly, although it is intuitive that optimization of such comorbidities should reduce the risk of poor outcome, there are little data to support such hypotheses (e.g., there are no reliable studies to date demonstrating that preoperatively reducing hemoglobin A1c [HbA1c] levels in patients with diabetes results in improved postoperative outcomes). TABLE 37-1 Some Resources to Facilitate Assessment and Optimization of Comorbidity In recent years, there has been a surge of interest in frailty in the medical, surgical, and anesthetic literature. In various surgical populations, frailty has been described as an independent risk factor for postoperative morbidity, mortality, prolonged hospitalization, and institutional discharge. Combining a measure of frailty (based on Fried criteria) with other preoperative risk assessment tools (e.g., American Society of Anesthesiologists [ASA] class, Lee index) increases the predictive power relating to postoperative morbidity, length of stay, and institutionalization.20,21 Furthermore, frailty is common in older surgical patients, with a quoted prevalence of between 40% and 50% in those undergoing elective surgery.21–25 This is in comparison to the cited prevalence of frailty in less than 10% of older community-dwelling individuals (aged 65 to 74 years 26), suggesting the relative vulnerability of the older surgical population. The cause of frailty is incompletely understood, but is thought to be related to the dysregulation of inflammatory pathways, with several inflammatory cytokines independently associated with frailty, including interleukin-6, tumor necrosis factor-α and chemokine ligand-10.27 Many conditions that are treated surgically (e.g., neoplastic conditions, degenerative or inflammatory arthropathies, arterial pathology) also result in the dysregulation of inflammatory processes. Thus, frail older adults may be more susceptible to developing such diseases or, alternatively, patients with such inflammatory, neoplastic, or vascular-type pathology may be more likely to be frail. Interpreting the literature examining frailty in surgical patients is hampered by inconsistent definitions of frailty and the use of different tools for measuring frailty. The measurement of frailty will depend on the intention (e.g., screening, case finding, assessment, prognostication), setting (e.g., research, clinical, community, inpatient, outpatient), and clinician (e.g., researcher, allied health care professional, geriatrician). At present, two approaches are generally used—scoring systems based on assessment across multiple domains, which include comorbidity, cognition, function, and psychosocial status (e.g., Edmonton Frail Scale, Canadian Study of Health and Aging [CSHA] Clinical Frailty Scale, Groningen Index) or surrogate single measures, such as grip strength, gait speed, or timed get-up-and-go (TGUG) test. The anesthetic literature tends to focus on the use of surrogate markers. This approach has two potential drawbacks. First the sensitivity and specificity of these surrogate markers in identifying frailty are not yet well established and second, identifying frailty to use it simply as a predictor of outcome may limit the potential to modify the perioperative risk related to frailty. The more detailed multidomain scoring systems may be more useful in this situation to identify individual components of frailty that can be modified using targeted interventions. For example, patients could be assessed using a tool such as the Edmonton Frail Scale to screen for frailty-associated perioperative risk, prompting optimization in the high-risk group using comprehensive geriatric assessment. Such an approach has yet to be evaluated.28 Cognitive syndromes are commonly encountered in older adult patient undergoing surgical procedures. To date, the literature has lacked clarity regarding the causation, overlap, or relationship among postoperative delirium, postoperative cognitive dysfunction, and longer term cognitive impairment. Furthermore, and possibly incorrectly, these terms are sometimes used interchangeably. Postoperative delirium (POD), similar to delirium attributable to a medical cause, is well defined by the DSM-5 (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition) criteria. It is known to be common, occurring in about one third of patients following hip fracture fixation29 and open abdominal aortic aneurysm repair.30 Regardless of the surgical subspecialty, POD is consistently shown to be an independent predictor of postoperative morbidity, mortality at up to 1 year after surgery,31 and new institutionalization at hospital discharge.32 Furthermore, it has emotional and psychological sequelae beyond the index period, not only for the patient, but also for caregivers and staff,33 and can worsen the trajectory of underlying cognitive impairment. Reliable and valid tools for the assessment of delirium risk are still lacking, but a pragmatic interpretation of the robust literature on delirium predictors can be interpreted into preoperative clinical practice.3 In contrast, another entity, described as postoperative cognitive dysfunction (POCD), is less clearly defined, although it is often described as neurobehavioral change occurring in the postoperative period. Its natural history has not been clearly delineated, and longer term consequences are not yet described. Interpretation of the literature is hampered by the use of various neurocognitive assessment tools, the use of different cutoff values for what constitutes change, and the differing time points at which cognition is assessed.34 The main limitation in the published research examining POCD is the lack of systematic identification of POD, which makes it difficult to conclude that POD and POCD are distinct entities. This picture is further confounded by the high prevalence of underlying cognitive impairment or dementia in the older surgical population, which is often unrecognized at preoperative assessment and not fully accounted for in the literature examining POCD.35–37 Cognitive impairment or dementia is relevant during the perioperative pathway of care for several reasons—it raises the likelihood that the patient may not have the capacity to consent to surgery, it influences the shared decision making process, and it is associated with adverse in-hospital outcomes, including increased falls, delirium, and longer length of hospital stay. Furthermore, there are specific considerations, such as the patient taking cholinesterase inhibitors as a treatment for dementia, because these agents can potentiate the actions of muscle relaxants used in general anesthesia. Although the preoperative assessment clinic may not be the most appropriate setting for the formal diagnosis of dementia, it remains important to include cognition as part of the holistic assessment, given that there are such clear implications on outcome. Assessment should include screening for undiagnosed cognitive impairment and a description of severity in known dementia using tools and measures such as the Montreal Cognitive Assessment validated across geriatric populations.12 Surgery can be defined as elective (performed at a time that suits the patient and surgeon), urgent (performed within 24 hours of admission), or emergency (carried out within 2 hours of admission or in conjunction with resuscitation).2 Within the elective group, the timing will depend on the pathology; for example, surgery for neoplastic pathology is more urgent than joint replacement for degenerative disease. Emergency and urgent surgery remain higher risk than elective surgery in terms of morbidity and mortality. This relates to the physiologic insult of an acute illness, with the associated so-called cytokine storm that it induces. It is therefore preferable, where possible, to perform elective surgery rather than postponing surgery until presentation as an emergency. For example, the outcome for a patient with a known abdominal aortic aneurysm measuring more than 6.5 cm in diameter will be much improved if the surgery is performed electively rather than as an emergency at the time of rupture. Surgery has evolved dramatically over the past 20 years, now using new techniques such as minimally invasive and robotic surgery. Such approaches can reduce surgical insult, thereby reducing duration of hospital stay and improving outcomes. Examples include the use of endovascular aortic aneurysm repair, which allows early mobilization, functional recovery, and reduced length of stay and, although there is no longer term mortality benefit over open repair, the rapid recovery has clear advantages for a frail older patient.38 Another example is holmium enucleation of the prostate (HoLEP), which reduces the risk of postoperative hyponatremia in comparison to transurethral resection of the prostate, which may be particularly relevant in a patient with an underlying electrolyte disturbance. However, the geriatrician should be aware of some of the practicalities of such approaches, which may have adverse implications for the frail older patient. For example, minimally invasive or keyhole procedures often require a longer period of general anesthesia (than open surgery) and often require a patient to be head down throughout the operation. This may not be appropriate for certain patients—for example, for those with underlying autonomic dysfunction secondary to diabetes. Overall, however, the significant advantages of newer techniques should not be underestimated. The major advances in anesthesia that are relevant to the frail older adult patient include the evolution of regional anesthetic techniques, technologic advances in intraoperative monitoring, and new modalities for the delivery of analgesia. There is a perception that regional anesthesia may pose less of a physiologic insult than general anesthesia, but the evidence does not suggest a significant difference in postoperative outcome between the two. This may be because primary outcomes studied do not directly relate to anesthesia (e.g., length of hospital stay and 30-day mortality) or because studies are confounded by the frequent concomitant administration of intravenous sedation with regional anesthesia.39 Advances in monitoring may reduce the incidence and severity of postoperative complications. For example, monitoring of intraarterial blood pressure is now routine to prevent, diagnose, and treat hypotension, thus reducing the risk of vital organ perfusion problems, including cardiac and cerebral ischemia. Bispectral index monitoring (BIS) can be used to guide the depth of anesthesia and sedation, with possible reduction in hypotensive episodes and postoperative cognitive dysfunction,40 and neuromuscular function monitoring could avoid prolonged neuromuscular blockade. Although goal-directed fluid therapy using technology such as esophageal Doppler monitoring has been widely advocated,41 the evidence in older adult patients is limited. This may be because aging can affect the compliance of the aorta so that cardiac output may be overestimated and lead the clinician to deliver insufficient fluid resuscitation. Poorly controlled preoperative pain can increase analgesic requirements postoperatively42 and, as such, requirements for preoperative analgesia should be actively reviewed and adjusted. Although it is widely acknowledged that inadequate control of postoperative pain results in a poor outcome (e.g., increased risk of delirium, immobility), it is often poorly assessed and treated, particularly in patients with cognitive impairment. This is despite the availability of guidance and protocols outlining the indications for and use of multimodal analgesia (including pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic approaches), which have been demonstrated to improve the patient experience.43 Although evidence is limited showing that frail older patients can use modalities such as patient-controlled analgesia, expert consensus advocates the use of such modalities, even in those with cognitive impairment. The benefits of early mobilization with neuroaxial blockade are particularly important in frail older patients for reducing the risk of respiratory complications and functional decline. The measurement of outcomes in the surgical and anesthetic literature has traditionally focused on clinician-reported outcomes and process measures. There has been an emphasis on describing postoperative surgical and medical morbidity and 30-day mortality. Surgical morbidity is often described as individual complications (e.g., reoperation rates, wound complications), whereas composite measures of medical morbidity (e.g., cardiovascular, respiratory, and renal complications) are frequently reported using measures such as postoperative morbidity survey (POMS), or major adverse cardiac events (MACE). Thirty-day postoperative mortality is now widely reported and, in most settings, will include adjustment for baseline characteristics of the patient population. Process measures such as length of hospital stay and readmission rates can provide useful measures of quality and efficiency of care, but may be affected by local medical, rehabilitation, and care services, resulting in the potential for misinterpretation. These clinician-reported outcomes and process measures are important, are relatively easy to measure, and provide a measure of safety, but they have limitations in the evaluation of effectiveness, efficiency, and quality of perioperative care. This is particularly the case for frail older surgical patients; if the baseline descriptors fail to capture their medical and functional complexity accurately, the frequency and severity of observed adverse outcomes may appear exaggerated. There is concern that publication of 30-day mortality may, on the one hand, deter surgery in high-risk patients and surgery for palliation and, on the other hand, may paradoxically influence postoperative decision making. For example, once a patient has had surgery, even with palliative intent, there may be a misplaced or futile emphasis on preserving or extending life at any cost simply because the patient has undergone a surgical procedure. To deliver patient-centered efficacious care, it is imperative to measure patient-reported outcomes (PROMs) along with clinician-reported outcomes. The tools currently available include generic measures of PROMs, such as the EuroQol Quality of Life Scale (EQ-5D), Short Form-36 (SF36), or more disease-specific measures, such as the Oxford Hip and Knee Score. However, to inform clinical practice, patient-reported outcomes should also include measurement against the goals of surgery. For example, these could include the impact of peripheral arterial bypass surgery on postoperative exercise tolerance at 3 months or the effect of palliative surgery for an obstructing colonic cancer on nausea and vomiting. Furthermore, outcome reporting should include information on the unintentional effect of surgery on functional and cognitive status. Many older patients and their caregivers request such information, but to date there are limited data and, where it does exist, suggests that functional and cognitive recovery to preoperative baseline may take 6 to 12 months.10,44 Most of the existing evidence regarding postoperative functional recovery comes from the hip fracture population. This may relate to the now long-established involvement of geriatric medicine in the care of hip fracture patients, resulting in more of a focus on traditional geriatric syndromes. The advent of PROMs has prompted the need for clear communication and documentation of the intended benefit of surgery between the health care team and the patient and caregivers. This can provide an opportunity to discuss alternative treatment options, postoperative management, including the use of life-supporting treatments, and resuscitation status, thus informing advance care directives. The effectiveness of patient engagement can be measured in terms of patient experience, thus helping formulate measures for patient-reported experiences (PREMs).

Surgery and Anesthesia in the Frail Older Patient

Introduction

The Frail Older Surgical Patient

Physiologic Reserve

Multimorbidity

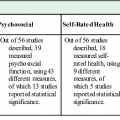

Frailty

Cognitive Syndromes

Surgical and Anesthetic Considerations for the Geriatrician

Timing of Surgery

Surgical Techniques

Anesthetic Techniques

Surgical Outcomes

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree