Supportive and Palliative Care

Ahmed Elsayem

Eduardo Bruera

INTRODUCTION

Palliative care is a discipline that strives to alleviate the physical and psychological suffering of patients and their families and to allow them to express their maximum potential during the course of their illness.

Patients with cancer of the head and neck may suffer from severe symptoms, including pain, anorexia, fatigue, cachexia, dyspnea, and psychological distress. In addition, cancer treatments such as surgery, radiation, chemotherapy, and immunotherapy have adverse effects such as mucositis, neutropenia, infection, neurocognitive dysfunction, and psychological distress due to extensive surgical procedures. The purpose of this chapter is to discuss the assessment and management of these complex symptoms in patients with cancer of the head and neck at all stages of their disease.

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS ASSOCIATED WITH CANCER OF THE HEAD AND NECK

Cancer of the head and neck is frequently associated with many physical symptoms related to the cancer itself or to associated treatment. Surgery and radiation therapy are the main modes of treatment, although chemotherapy is frequently used.1 Radiation therapy doses sufficient to produce tumor regression are associated with mucositis and xerostomia (dry mouth).2 In addition, significant disfigurement and functional loss often accompany surgical interventions.3 Many vital functions such as taste, speech, mastication, and swallowing can be affected.4 Late effects of treatment, particularly radiation ports that include incidental brain exposure, may cause significant cognitive impairment.5 Cancers of the head and neck are particularly problematic because of their impact on the airway and gastrointestinal tract, which results in significant compromise of breathing and nutrition. Table 34.1 describes the incidence of the most common symptoms of advanced cancer of the head and neck.

Pain

Pain is a common symptom in this patient population. In most patients with advanced cancer, chronic pain is due to direct stimulation of afferent nerve structures by the primary or metastatic cancer. Pain associated with direct tumor involvement occurs in 65% to 85% of patients with advanced cancer.6 Cancer therapy accounts for 15% to 25% of pain syndromes.7 Pain syndromes are categorized as nociceptive or neuropathic. Nociceptive pain is further divided into somatic and visceral. For example, nociceptive pain related to cancer of the larynx or bony metastases results from activation of pain receptors in these tissues and organs. Neuropathic pain, such as trigeminal or glossopharyngeal neuralgia, results from direct injury to the peripheral or central nervous system. Somatic pain is usually localized and tender to pressure; neuropathic pain is often described as burning or shooting.8

Patients with advanced cancer often have chronic, constant pain intermittently punctuated by acute breakthrough pain. Patients may have acute pain following certain procedures, such as postoperative pain or radiation-induced mucositis. Incidental pain is usually acute and may be triggered by certain maneuvers such as swallowing, mastication, or speech.

Weight Loss

Cachexia-anorexia occurs in more than 80% of patients with advanced cancer and is a major factor contributing to morbidity and mortality.9 Patients with cancer of the head and neck are particularly susceptible because of the effects of cancer and its treatment on eating, including altered taste and difficulty chewing and swallowing. Cachexia is characterized by weight loss, wasting, anorexia, and change in body image with resulting asthenia and psychological distress.

Fatigue

Fatigue is the most frequent symptom of advanced cancer.10 It is characterized by unusual and profound tiredness after minimal effort, accompanied by an unpleasant sensation of generalized weakness. Cancer-related fatigue, unlike fatigue in a person who is not ill, does not improve with rest.

Psychological Distress

Patients with cancer of the head and neck face enormous psychological distress because of the structural and functional deficits associated with the cancer and its treatment. Facial disfigurement and loss of taste, speech, and sometimes sight result in altered body image, low self-esteem, and possibly depression.11 Moreover, patients with cancer of the head and neck often have a history of chronic alcohol and tobacco use12 accompanied by physical and neurocognitive disabilities.13 It is estimated that 80% of patients with cancer of the head and neck have such a history, which may complicate their care and rehabilitation.14

ASSESSMENT OF SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

Pain

Lack of expertise among health care professionals in the use of assessment tools for pain and other symptoms is the main reason for poor management of symptoms.15 Patient selfreporting should be the primary source of information for the

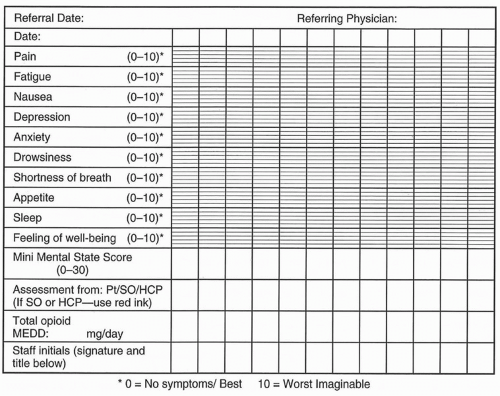

measurement of symptoms. Observer ratings of symptom severity correlate poorly with patient ratings. Simple tools such as the visual analogue scale (VAS), numeric rating systems (NRSs), and verbal descriptor scales have proved to be effective and reproducible means of measuring pain and other symptoms.16 Other scales include the Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale (MSAS).17 The Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS) is the most common clinical tool for the assessment of pain and multiple other physical and psychosocial symptoms in the clinical setting (Fig. 34.1). This tool is copyright-free and can be completed by the patient in a few minutes. Pain in cancer patients is frequently complicated by a high level of distress.18 The emotional suffering experienced by cancer patients manifests itself as fear, anxiety, and depression, which result in increased sensitivity to pain and other symptoms.19 Therefore, a unidimensional approach to pain that considers 100% of the pain complaint as nociceptive may not address other treatable conditions, thus depriving the patient of appropriate additional therapies.

measurement of symptoms. Observer ratings of symptom severity correlate poorly with patient ratings. Simple tools such as the visual analogue scale (VAS), numeric rating systems (NRSs), and verbal descriptor scales have proved to be effective and reproducible means of measuring pain and other symptoms.16 Other scales include the Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale (MSAS).17 The Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS) is the most common clinical tool for the assessment of pain and multiple other physical and psychosocial symptoms in the clinical setting (Fig. 34.1). This tool is copyright-free and can be completed by the patient in a few minutes. Pain in cancer patients is frequently complicated by a high level of distress.18 The emotional suffering experienced by cancer patients manifests itself as fear, anxiety, and depression, which result in increased sensitivity to pain and other symptoms.19 Therefore, a unidimensional approach to pain that considers 100% of the pain complaint as nociceptive may not address other treatable conditions, thus depriving the patient of appropriate additional therapies.

Table 34.1 Incidence of Common Signs and Symptoms of Advanced Cancer of the Head and Neck | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

Assessment of pain should address the cause of the pain and should measure the intensity, onset, duration, location, character, and factors that aggravate and relieve it. Regular reporting in the patient’s medical records of the patient’s pain and other symptoms assists the team that is treating the patient in monitoring these symptoms and providing appropriate treatment. The ESAS (Fig. 34.1) graphically displays the most common symptoms reported among cancer patients.20,21,22

A positive history of alcoholism may be associated with a higher risk for the use of medications to cope with emotional distress.23,24 Well-validated tools are available for quantifying alcohol use, both current and past,25 although there are limitations to the accuracy of any self-report questionnaire about alcohol use. Some groups have found that a history of alcoholism is an independent prognostic factor for the development of opioid dose escalation and opioid-related neurotoxicity26 and that such a history predisposes the patient to preexisting cognitive deficits.27 Simple bedside screening of alcohol intake shows a very high frequency of undocumented alcoholism. These patients are at a higher risk of chemical coping with opioids.28 Among patients with head and neck cancer, those who score positive in the CASE questionnaire are at high risk of opioid use 3 months and 6 months after completion of radiation and/or

chemotherapy. Although patients with a significant alcohol history may need more frequent monitoring and counseling to achieve good pain control, a history of substance abuse or emotional problems is not an indication for limiting pain treatment.

chemotherapy. Although patients with a significant alcohol history may need more frequent monitoring and counseling to achieve good pain control, a history of substance abuse or emotional problems is not an indication for limiting pain treatment.

Unfortunately, pharmacologic treatment of pain may lead to worsening of other symptoms such as opioid-related nausea, constipation, and delirium. Given the complexity of the interaction among the various physical and psychosocial domains, there is a growing acceptance that the assessment of pain in cancer patients requires a multidimensional approach.

Weight Loss

Weight loss is the main clinical finding in patients with cancer cachexia. In patients with cancer of the head and neck, this may result from local factors affecting food intake such as altered taste, smell, or swallowing. It may also be due to decreased appetite. A weight loss of 10% or more usually indicates moderately severe malnutrition.29 The presence of edema, ascites, or pleural effusion may make the interpretation of weight loss difficult. Assessment of caloric intake can be made at the bedside by a nutritionist or a trained nurse. Anorexia is a major target of both nutritional and pharmacologic interventions.

Fatigue

Fatigue is often measured according to subjective assessment and functional capacity. Commonly used performance status scales, such as the Karnofsky Performance Scale and the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) scale, do not adequately measure fatigue. Although there are a number of tools for the assessment of the severity of fatigue, in the clinical setting, it can be monitored using multidimensional tools such as ESAS.30

MANAGEMENT OF SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

Pain

Successful management of pain depends on the physician’s ability to assess the patient and the pain, identify the pain syndrome, and formulate and discuss the treatment plan with the patient. A pharmacologic approach is the primary treatment provided for cancer pain. In more advanced and complex cases, in which suffering and psychological distress complicate pain perception, a multidisciplinary approach is required for effective pain management. The World Health Organization proposed a simple analgesics ladder for the pharmacologic management of cancer pain, which has been shown to be safe and effective. This ladder begins with simple nonopioid analgesics, proceeds to weak opioids, and then recommends strong opioids as the disease progresses and pain expression escalates. Most patients need opioids for the management of cancer pain. Patients should receive appropriate counseling and information regarding their pain, opioids, medication adverse effects, and the costs of treatment.

Nonopioid Analgesics

Acetaminophen or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are effective analgesics for patients with mild cancer pain and can be combined with opioids such as codeine and oxycodone in patients with moderate to severe pain.31 Acetaminophen does not inhibit prostaglandin synthesis or affect platelet function; therefore, it is widely used in the treatment of cancer pain, either alone or in combination with opioids such as codeine or oxycodone. The major toxicity of acetaminophen is its hepatotoxic effect, which is dose related. Therefore, the cumulative daily dose should not exceed 4 g. The main limitations of NSAIDs include their relatively flat dose-response curves and associated gastrointestinal, renal, and bleeding adverse effects. These effects are related to the inhibition of the enzyme cyclooxygenase-1. Newer generations of cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors such as celecoxib and rofecoxib have a lower frequency of toxicity and are effective when used alone or in combination with opioids.

Opioids

Opioids remain the mainstay in the treatment of cancer pain. Opioids interrupt pain perception at different levels in the central nervous system. Table 34.2 summarizes the general principles that apply to opioid treatment of cancer pain.

Routes of Opioid Delivery. The oral route of opioid administration is preferable because it is safe, effective, and convenient and can be used in the home setting. However, 80% of patients taking oral opioids require an alternative route of administration before death.32 The intravenous route is more suitable for the immediate postoperative period and when the gastrointestinal route is not available because of concerns about wound healing, vomiting, dysphagia, or mucositis. Patient-controlled analgesia (PCA), administered with different types of pumps, is a widely used technique that has proved to be effective in the treatment of pain in hospitalized patients, especially during the postoperative period.33 Although the overuse of medication by confused or psychologically impaired patients, particularly those with a history of addiction, is possible, this is easily handled by limiting the number of doses that can be administered over a given period of time. The subcutaneous route is a safe and effective mode of opioid delivery wherein opioids can be administered by the patient or a family member with the use of a preloaded syringe.34 The rectal route is also safe and effective, but it is uncomfortable for many patients. The transdermal route (patch) is an effective alternative to the oral route and is more suitable for patients with stable pain complaints who need a relatively small dose of opioids. Drugs such as morphine and hydromorphone can be given safely through the transdermal route.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree