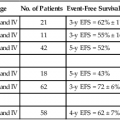

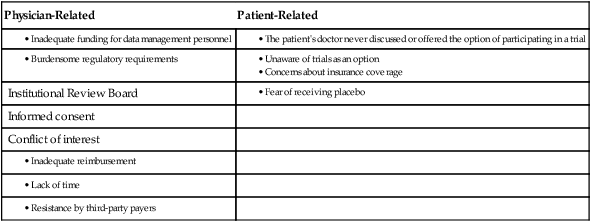

Jeffrey S. Abrams, Margaret Mooney, James A. Zwiebel, Michaele C. Christian and James H. Doroshow • Cancer clinical trials provide the evidence on which sound oncology practice is based. • Providing a greater efficiency in implementing clinical trials and achieving enrollment rapidly has been a major goal of the National Cancer Institute, cancer centers, the biopharmaceutical industry, and patient advocacy groups. • Physicians in private practice have many opportunities to participate in clinical trials sponsored by the National Cancer Institute and/or the biopharmaceutical industry. • Physicians and patients have online access to all U.S. sponsored clinical trials at clinicaltrials.gov and have access to additional information about cancer trials at cancer.gov. • Successful participation in clinical trials includes the following clinical components: • Affiliation with an institution or network that provides scientific and administrative support, such as the following: • Many organizations now provide access to clinical trials and/or provide the necessary training and certification; relevant Web sites are included in this chapter. The NCI supports the development of more than 100 agents for cancer treatment and prevention (many in collaboration with pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies) and has an extensive clinical trials system that encompasses treatment, prevention, and cancer control studies. More than 800 trials are active at any given time, and several hundred new trials open each year. In the treatment area, the NCI has programs for early therapeutics development (primarily phases I and II trials), including many sites with grants and contracts to complete these early trials. The NCI also supports a large program of Clinical Trials Cooperative Groups that conduct later-phase trials, predominantly pilot studies and phase III trials. Clinical Trials Cooperative Groups funded by the NCI provide a standing mechanism for performing large-scale multicenter treatment, cancer control, diagnostic, and prevention trials. Phase III trials are conducted nationally, and a member of any NCI-supported Cooperative Group is able to participate in trials conducted by any of the Groups, because they all share a common menu of trials on the Cancer Trials Support Unit Web site (www.ctsu.org). Over the years, this system has supported an experienced cadre of clinical researchers, biostatisticians, and research support staff who can respond to new clinical discoveries by organizing definitive phase III clinical trials. Because of their size and complexity, these trials require extensive infrastructure support to manage the necessary regulatory and data-reporting tasks. Although these Cooperative Group trials have provided a significant proportion of the evidence on which oncology practice is based, public advocacy for more rapid progress, increasing fiscal pressures on medical practice, and the accelerated pace of drug discovery caused the NCI to review and restructure aspects of its clinical trials program beginning in 1998. The major goals of these restructuring efforts were to increase access to NCI trials for patients and their physicians; eliminate barriers to participation in clinical trials; improve the coordination and cooperation among the functionally diverse elements of the NCI clinical trials program, including relationships with industry and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA); improve the prioritization process for developing clinical trials leading to increased scientific quality; enhance the standardization of tools for clinical trial design and data capture; increase operational efficiency so that trials could be executed in a more timely manner; and most recently, restructure the Cooperative Groups into a tightly integrated network by reducing the number of Groups and changing the review criteria for funding to emphasize collaboration and cooperation. Through surveys among physicians and the public, it was found that the obstacles to accrual in adult oncology were multifactorial (Table 20-1).3–3 With these barriers in mind, the NCI undertook a series of comprehensive analyses of how it conducts and funds clinical trials by involving a wide range of stakeholders that included Cooperative Group and Cancer Center leaders, patient advocates, representatives from the FDA and the pharmaceutical industry, and government staff. The detailed reports of these reviews are available online: the 2005 review (http://integratedtrials.nci.gov/ict/ctwg_report_June2005.pdf from 2005), the 2008 review (http://ccct.cancer.gov/files/OEWG-Report.pdf), and most recently, the 2010 Institute of Medicine (IOM) Report (http://books.nap.edu/openbook.php?record_id=12879). Several important projects were launched based on the recommendations, all of which were aimed at modernizing NCI’s clinical trials regulatory and data collection systems, opening trial access to more patients and investigators, and simplifying the role of local Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) in multiinstitutional clinical trials. New opportunities were created for community physicians to participate in a broad array of clinical trials, and new tools were created to enable this participation. Two major initiatives, the Cancer Trials Support Unit (CTSU) and the Central Institutional Review Board (CIRB), were uniformly supported by all stakeholders and have now become integral parts of NCI’s clinical trials system; they are described next. Table 20-1 Barriers to Clinical Trial Participation The NCI CTSU is designed to facilitate one-stop online access to a broad menu of phase III trials, large phase II trials, and selected international collaborative trials by a national network of NCI investigators. Network investigators can access the CTSU menu of treatment trials from a public Web site (www.ctsu.org). The scientific leadership for each study remains within the organization that developed the trial, but patient enrollment can come from any network physician across the country, and all patient enrollment is handled through CTSU’s central registration system, the Oncology Patient Enrollment Network. By providing more physicians and their patients with the opportunity to choose from a broader menu of trials, the CTSU promotes faster accrual to individual trials, allows increased access and additional treatment options to more patients nationwide, and renders trials involving uncommon cancers more feasible. Although the clinical trials menu and centralized patient enrollment are the most visible aspects of the CTSU, another major function of the CTSU is its centralized regulatory database. For all physicians in the network, the CTSU maintains important demographic information about their sites or practices, including clinical trial group affiliation and academic/practice affiliation(s), Office for Human Research Protection assurance numbers for their sites, IRB approvals for specific protocols, and conflict of interest forms for investigators. This process enables physicians, nurses, and clinical research associates to register once annually instead of having to register for each clinical trial group or trial in which they participate. Centralizing regulatory data has reduced the workload for investigators in the field, consolidated duplicative work, and allowed clinical trial group staff to partially offload this activity to the CTSU and focus instead on protocol development and analysis. In NCI-sponsored multicenter trials, the identical protocol is carried out at many sites, often including as many as 100 different practices; each site requires its own local IRB (LIRB) to conduct an initial full-board review and subsequent annual reviews, adverse event reviews, and amendment reviews. These multiple IRB reviews create a largely redundant, time-consuming workload at these sites, compounding the ever-mounting pressures on the nation’s IRB system, which have been well documented.4 To provide an idea of the scope of the duplicative effort that occurs, consider that NCI has more than 8000 registered investigators at more than 1500 sites. On average, there are 160 ongoing phase III trials and 30 new trials entering the NCI system annually, resulting in approximately 16,000 IRB reviews (3000 initial reviews) conducted each year.4 In addition, investigators often mention that the amount of time, paperwork, and funding required for them to obtain IRB approval is a serious barrier to opening trials. These factors provided the impetus for the NCI to develop a new, centralized approach to human subjects protection for its large phase III trials program.

Structures Supporting Cancer Clinical Trials

The attitude and commitment of the physician

The attitude and commitment of the physician

Sufficient preparation and infrastructure

Sufficient preparation and infrastructure

Trained staff, including at least some of the following:

Trained staff, including at least some of the following:

Biopharmaceutical industry network

Biopharmaceutical industry network

Access to an authorized Institutional Review Board

Access to an authorized Institutional Review Board

Access to adequate laboratory facilities to process protocol-required specimens

Access to adequate laboratory facilities to process protocol-required specimens

Adherence to good clinical practices

Adherence to good clinical practices

Accurate and timely data reporting

Accurate and timely data reporting

Proper maintenance of primary source documentation

Proper maintenance of primary source documentation

Adequate preparation for on-site audits

Adequate preparation for on-site audits

National Cancer Institute–Sponsored Clinical Trials Activities

Physician-Related

Patient-Related

Institutional Review Board

Informed consent

Conflict of interest

Cancer Trials Support Unit

Central Institutional Review Board

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Structures Supporting Cancer Clinical Trials