NSEa

Chromogranin

S-100

CK-PANb

DOG-1c

CD117 (c-kit)

CD34

Gangliocytic paraganglioma

+ (all 3 cell types)

+ (mostly described in epithelial component)

+ (spindle cell component)

+ 50 % of cases (only epithelioid component)

–

–

–

Schwannoma

+/– (+ in approx 25 % of cases)

–

+ (strong and diffusely positive)

–

–

–

– (rare cases show focal positivity)

GIST

–

–

Mostly – (5 % focal positivity)

–

+ (>90 %)

+ (>90 %)

+ (66 %)

Of the remaining 20–25 % of GISTs without a c-kit mutation, approximately one-third harbor a mutation in the platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR), another receptor tyrosine kinase with similar growth-promoting properties to c-kit [15, 16]. The remaining GISTs, which do not display mutations in either c-kit or PDGFR, are referred to as wild-type tumors. This nomenclature, however, is slightly inaccurate, as these tumors have a high incidence of other known oncogenic mutations, such as BRAF [17], SDH [18, 19], RAS [20], and NF1 [21]. Thus, GISTs display a unique pattern of oncogenic traits. This knowledge has led to major breakthroughs in their diagnosis and treatment.

Diagnosis

It is important to note that GISTs can grow quite large prior to causing symptoms. For example, an Italian series of 47 consecutive patients diagnosed with GIST correlated symptoms with tumor size. Interestingly, the average size of symptomatic GISTs was 8.9 cm, while the average size of incidentally found GISTs was 2.7 cm [4]. Accordingly, it is estimated that 25 % of GISTs are found incidentally [4, 8, 22]. Symptomatic patients present most frequently with either abdominal discomfort or gastrointestinal bleeding and subsequent anemia [23].

Endoscopic biopsy of the submucosal tumor represents the preferred diagnostic method, which prevents tumor seeding in the abdominal cavity. Histologic diagnosis is of particular benefit if there is any suspicion for other sarcoma subtypes or situations involving a marginally resectable or unresectable tumor to guide chemotherapy. However, if a submucosal lesion in the stomach is easily resectable and has characteristic features of GIST, biopsy is not required prior to resection.

Typically, the diagnosis is made by immunohistochemistry displaying a c-kit positive stromal malignancy. However, it is worthwhile to discuss the differential diagnosis for a c-kit positive lesion. Importantly, metastatic melanoma should always be considered, as they are commonly c-kit positive. Other common malignancies, which stain c-kit positive, include seminomas and small cell lung carcinomas. Additionally, 50 % of angiosarcomas, 50 % of Ewing’s sarcomas, and 30 % of neuroblastomas are c-kit positive [24].

The diagnosis may be complicated by the 5 % of GISTs, which stain negative for c-kit. The most important point to remember concerning these situations is that a pathologist experienced in GIST diagnosis must be employed. Multiple additional diagnostic methods have been applied in this situation, including the detection of PDGFR-A [25], BRAF [17], protein kinase C-theta [26], and DOG1 (discovered on GIST1) [27].

Once the diagnosis is made histologically, further imaging is of limited utility. Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) has been demonstrated to better characterize tumor size and aid in prognostic staging. Additionally, EUS with fine needle aspiration biopsy is a viable, less invasive option for histologic diagnosis, yielding a sensitivity of approximately 84 % [28]. Nodal staging is of limited value as well, as lymphatic spread is not characteristic of a GIST. Further, staging is typically unnecessary for the head, neck, and chest, as extra-abdominal metastases are exceedingly infrequent.

Risk Stratification

Pathologic and clinical features of GISTs affecting prognosis remain controversial. A prognostic nomogram developed at the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center from 127 patients has been subsequently validated in two larger cohorts of GIST patients. The results successfully predicted recurrence-free survival and established the current model of risk stratification recommended in GIST. Based on their conclusions, high-risk features include size greater than 3 cm, mitotic rate exceeding five per high-powered field (HPF) and a non-gastric location [29]. Subsequent investigations have confirmed the predictive value of size, mitotic rate, and location on prognosis [30–32]. An example of a widely used risk stratification model employed by the 2008 National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines is displayed in Table 2.

Table 2

Risk stratification of primary GISTs

Tumor parameters | Risk for progressive diseasea (%), based on site of origin | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Mitotic rate | Size (cm) | Stomach | Jejunum/ileum | Duodenum | Rectum |

≤5 per 50 HPF | ≤2 | None (0 %) | None (0 %) | None (0 %) | None (0 %) |

>2, ≤5 | Very low (1.9 %) | Low (4.3 %) | Low (8.3 %) | Low (8.5 %) | |

>5, ≤10 | Low (3.6 %) | Moderate (24 %) | Insufficient data | Insufficient data | |

>10 | Moderate (10 %) | High (52 %) | High (34 %) | High (57 %) | |

>5 per HPF | ≤2 | Noneb | Highb | Insufficient data | High (54 %) |

>2, ≤5 | Moderate (16 %) | High (73 %) | High (50 %) | High (52 %) | |

>5, ≤10 | High (55 %) | High (85 %) | Insufficient data | Insufficient data | |

>10 | High (86 %) | High (90 %) | High (86 %) | High (71 %) | |

Medical Management

Prior to the development of imatinib, GISTs were treated with cytotoxic chemotherapy, yielding abysmal results. The median survival for tumors treated with cytotoxic chemotherapy was approximately 14–18 months [33]. As a result, cytotoxic chemotherapy is not recommended currently as a treatment for GIST. Imatinib treatment is now the standard of care, by NCCN recommendations.

The major role for adjuvant imatinib arose from a phase 3 trial, in which 713 patients were randomized postoperatively to receive imatinib versus placebo for 1 year [30]. Ninety-eight percent of patients in the imatinib group experienced 1-year recurrence-free survival compared to only 83 % in the placebo group. Additionally, at median follow-up of 20 months, 30 % of the placebo group had either recurred or died, compared to only 8 % of the imatinib group. Additionally, the benefits of imatinib were especially significant with larger tumors, with thresholds of 6 cm and 10 cm being analyzed [30]. A similar trial examined the duration of imatinib treatment postoperatively, comparing 36 months to 12 months of therapy. The 5-year recurrence-free and overall survivals were 66 and 92 % for 3 years of therapy and 48 and 82 % for 1 year of therapy, respectively [31].

Thus, the NCCN 2012 guidelines state that 1 year of adjuvant imatinib therapy is appropriate in intermediate and high-risk GISTs [34]. Based on the criteria discussed under risk stratification, features justifying adjuvant treatment with imatinib include 5 mitoses/50 HPF, size greater than 3 cm, non-gastric location or tumor rupture [30, 31]. Further, for GISTs at least 5 cm in size, 3 years of adjuvant imatinib is recommended [34].

Additionally, it is pertinent to discuss recommendations for neoadjuvant imatinib, as this directly affects the surgeon’s operative planning. Several trials have formed the foundation justifying preoperative administration of imatinib. The first is the RTOG 0132 phase 2 trial, in which 30 patients with primary GIST received 8–12 weeks of neoadjuvant imatinib. A partial response was observed in 7 % of patients, stable disease in 83 % of patients, and 2-year progression-free and overall survival was 83 and 93 %, respectively [35]. A similar trial employed a longer duration of therapy, examining 15 patients receiving 7–9 months of preoperative imatinib. In these patients, a median size reduction of 34 % was observed, and the 3-year progression-free survival rate was 77 % [36]. Of note, all patients in these trials received adjuvant imatinib as well. As insufficient evidence is available to conclude that neoadjuvant therapy leads to superior outcomes, it is currently recognized as a viable modality by the NCCN, but specific therapeutic guidelines have not been established [34].

A recently investigated dilemma facing the surgeon treating GISTs is whether preoperative imatinib can downstage a tumor or offer a less morbid resection. A recent investigation examined this question in 15 patients receiving preoperative imatinib with cytoreductive intent. In this group of patients, three out of four patients initially planned for abdominoperineal resection achieved successful sphincter sparing operations, while the fourth patient had a complete response and underwent no operation. These patients experienced no recurrence at 22 months of follow-up. Additionally, three out of five patients initially planned for total gastrectomy received successful partial gastrectomies. Three initially unresectable GISTs (one duodenal and two gastric GISTs) achieved R0 resections [36]. While small in scope, this investigation establishes a precedent for neoadjuvant imatinib when faced with a highly morbid resection.

Principles of Surgical Management

All extragastric GISTs are considered high risk and currently warrant resection when feasible. Regarding gastric GISTs, the current recommendation is resection if the tumor is at least 2 cm in size [34, 37]. Additionally, high-risk features that are radiographically evident and indications for resection include a heterogeneous mass with irregular borders or cystic components. Importantly, GISTs in locations representing high operative morbidity, such as the gastroesophageal junction, duodenum, and rectum, warrant extensive preoperative multidisciplinary review. The possibility of avoiding a radical resection with neoadjuvant imatinib should be considered.

It is important to note that incidental submucosal tumors less than 1 cm in size are frequently discovered on endoscopy. Although somewhat controversial, routine excision of these lesions is not recommended given their low propensity to progress into clinically significant tumors [38–44].

Current operative recommendations entail segmental resection to negative microscopic margins. Formal oncologic resection of uninvolved tissue and lymph node dissection are unnecessary, as they have shown no clinical benefit [33, 45]. It has even been suggested that re-excision of a microscopically positive margin (R1 resection) imparts little clinical benefit [46]. However, one recommendation, which has remained consistent, is to avoid tumor rupture during surgery. GISTs have the potential to seed intraperitoneal tumors. For this reason, open excisional biopsy should be avoided as well.

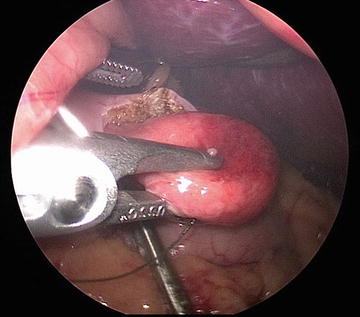

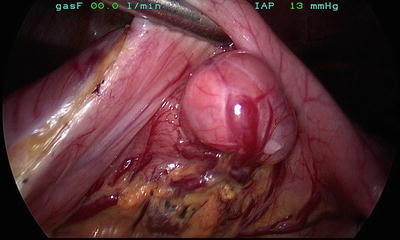

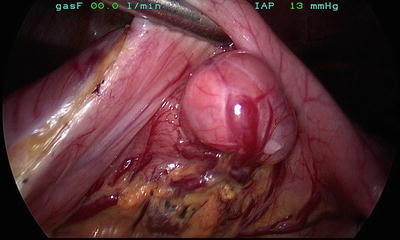

In addition to traditional open approaches, laparoscopic resection of gastric GISTs has been consistently associated with low recurrence rates, low morbidity, and shorter hospital stays in multiple series [47–51]. We have included multiple illustrations of our laparoscopic approach, including the typical submucosal appearance and dissection (Figs. 1, 2, 3, and 4).

Fig. 1

Typical external appearance of a gastric GIST