Patients with Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) who relapse following effective front-line therapy are offered salvage second-line chemotherapy regimens followed by high-dose therapy and autologous stem cell transplantation (HDT/ASCT). Randomized studies comparing HDT/ASCT with conventional chemotherapy in patients with relapsed refractory HL have shown significant improvement in progression-free survival and freedom from treatment failure but were not powered to show improvements in overall survival. For patients who relapse after salvage HDT/ASCT, novel therapies exist as a bridge to allogeneic SCT. In this article, we review indications and results of autologous and allogeneic SCT in HL.

Key points

- •

Autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) should be offered to patients who fail to respond to initial treatment and/or as salvage therapy.

- •

Patients who relapse early (<12 months) after initial therapy are a biologically poor prognostic group.

- •

A negative functional imaging (PET) before transplantation is associated with improved outcome.

- •

Reduced-intensity conditioning allogeneic SCT should be offered for patients who relapse after ASCT.

Introduction

Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) is a rare malignancy that has a bimodal distribution of incidence, with most patients diagnosed at between 15 and 30 years of age and another peak in those older than 55 years. It is estimated that in 2014, approximately 9190 people will be diagnosed with HL in the United States. Despite high success rates with initial chemotherapy, relapse occurs in 10% to 20% of patients with HL and a small minority is nonresponsive to initial chemotherapy. The standard management of these patients includes high-dose chemotherapy (HDT) followed by autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT). For patients who relapse after ASCT, eligible candidates may be offered allogeneic SCT (allo-SCT). In this article, we discuss the indications of SCT (autologous and allogeneic) in HL and also discuss the management of patients who relapse after transplantation. In addition, we review newer agents that are being incorporated into the routine management of HL and may impact indications for SCT as they are used earlier in the treatment course.

Introduction

Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) is a rare malignancy that has a bimodal distribution of incidence, with most patients diagnosed at between 15 and 30 years of age and another peak in those older than 55 years. It is estimated that in 2014, approximately 9190 people will be diagnosed with HL in the United States. Despite high success rates with initial chemotherapy, relapse occurs in 10% to 20% of patients with HL and a small minority is nonresponsive to initial chemotherapy. The standard management of these patients includes high-dose chemotherapy (HDT) followed by autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT). For patients who relapse after ASCT, eligible candidates may be offered allogeneic SCT (allo-SCT). In this article, we discuss the indications of SCT (autologous and allogeneic) in HL and also discuss the management of patients who relapse after transplantation. In addition, we review newer agents that are being incorporated into the routine management of HL and may impact indications for SCT as they are used earlier in the treatment course.

Indications for transplantation

ASCT is the standard of care for eligible patients with relapsed HL. Approximately half of these patients are rescued by this regimen intensity.

Current indications of ASCT in HL include the following:

- 1.

HDT/ASCT should be offered to patients as salvage therapy.

- 2.

HDT/ASCT may be offered as first-line therapy for patients who fail to achieve a complete response.

Current indications of allo-SCT in HL include the following:

- 1.

Allo-SCT should be offered to eligible patients who relapse following ASCT

Salvage regimens

Several studies have shown the importance of cytoreduction before proceeding with SCT ( Table 1 ). There is moderate evidence to support a single best salvage regimen as a recommended treatment option for patients with disease relapse before ASCT. Achieving a complete remission, as defined by the absence of any detectable disease using PET with fludeoxyglucose (FDG-PET) functional imaging before ASCT, has been shown to improve event-free survival (EFS). An ideal salvage regimen should therefore produce a high rate of response, with acceptable toxicity and should not hinder stem cell mobilization. Multiple combination therapies have been evaluated in phase II studies for pretransplantation salvage in patients with relapsed HL. Historically, Europeans have favored aggressive pretransplantation regimens, such as mini-BEAM or Dexa-BEAM (carmustine, etoposide, cytarabine, and melphalan). These regimens are, however, associated with significant treatment-related hematologic toxicities, including 5% treatment-related mortality. In the United States, platinum-based regimens with non–cross-resistant drugs, such as ICE (ifosfamide, carboplatin, and etoposide), ESHAP (etoposide, solumederol, cytarabine, and prednisone), or DHAP (dexamethasone, cytarabine, cisplatin) are preferred. The current salvage regimens induce a complete response (CR) rate of 19%–41% depending on the regimen used. There are no published randomized trials comparing the effectiveness of combination regimens.

| Regimen | n | Response Rates (%) | Author | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ORR | CR | |||

| ICE | 65 | 88 | 26 | Moskowitz et al, 2001 |

| mini-BEAM | 55 | 84 | 51 | Martin et al, 2001 |

| DHAP | 102 | 88 | 21 | Josting et al, 2002 |

| GDP | 23 | 69 | 17 | Baetz et al, 2003 |

| IGEV | 91 | 81 | 54 | Santoro et al, 2007 |

| GND | 90 | 70 | 19 | Bartlett et al, 2007 |

| IVOX | 34 | 76 | 32 | Sibon et al, 2011 |

| GV | 31 | 72 | 36 | Suyani et al, 2011 |

| ICE/aICE GVD | 97 | 60 (ICE) 52 (GVD) | Moskowitz et al, 2012 | |

Based on available data and current practice in US centers, we recommend ICE salvage as an effective choice in the absence of randomized studies or in the absence of a clinical trial. Other alternative regimens include gemcitabine-based regimens. It is also important to note that a diagnostic biopsy is mandatory to confirm relapse or progressive disease before salvage treatment.

Conditioning regimens

Preparative regimens before ASCT contain a combination of drugs with antilymphoma activity ( Table 2 ). Several regimens that include cyclophosphamide, busulfan, etoposide, melphalan, and lymphoid radiation have been widely used as conditioning regimens. The reported 100-day mortality is approximately 3% to 5%. The later treatment complications specifically in HL are of importance, as patients with HL are relatively younger at diagnosis and are susceptible to cumulative risks of developing secondary malignancies.

| Regimen | n | TRM (%) | Outcomes (%) | 2nd Malignancy (%) | Author | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OS | PFS | EFS | |||||

| TBI/Cy/Et | 28 | 0 | 61 | 43 | 0 | Stiff et al, 2003 | |

| BCNU/Cy/Et | 46 | 6.5 | 50 | 39 | 2.2 | ||

| Total | 74 | 4.1 | 54 | 41 | 1.3 | ||

| Bu/Cy/Et | 127 | 5.5 | 51 | 48 | 3.1 | Wadhera et al, 2006 | |

| TLI/CCE | 32 | 61 | 63 | Evens et al, 2007 | |||

| CCE | 16 | 27 | 6 | ||||

| Total | 48 | 4.2 | 48 | 44 | 4.2 | ||

| LACE | 67 | 3 | 68 | 64 | 3.8 | Perz et al, 2007 | |

| CBV | 43 | 7 | 57 | 63 | 53 | 2.3 | Benekli et al, 2008 |

| Bu/Cy | 19 | 5 | 41 | 31 | 11 | Lane et al, 2011 | |

| Bu/Mel | 49 | 85 | 57 | Kebriaei et al, 2011 | |||

| TLI/Cy/Et | 56 | 0 | 88 | 1.2 | Moskowitz et al, 2012 | ||

| CBV | 29 | 79 | 0 | ||||

| Total | 85 | 88 | 3.4 | ||||

Role of functional imaging before stem cell transplantation

FDG-PET is highly sensitive in predicting outcome in HL. PET/computed tomography (CT) performed at the end of initial treatment in advanced HL has a sensitivity of 43% to 100% in discriminating residual lymphoma from fibrotic masses. Therefore, PET/CT is a promising tool for predicting tumor response and progression-free survival (PFS). A few studies have addressed the role of FDG/PET in patients treated with salvage chemotherapy before stem cell transplantation, and have shown improved outcomes in patients who achieve a CR before HDT/ASCT. In a study by Moskowitz and colleagues, patients with pre-ASCT negative PET after 1 or 2 salvage regimens had an EFS greater than 80% as compared with 26% in patients with a positive PET pre-ASCT, highlighting the importance of pre-ASCT negative PET scan. Similarly, Sirohi and colleagues reported that the 5-year PFS and overall survival (OS) were 69% versus 44% and 79% versus 59%, respectively, for patients who were in CR or partial response (PR) at the time of HDT/SCT. Based on the currently available data, we recommend the use of standardized methods (Deauville scoring system) while reporting PET/CT. We favor proceeding with ASCT in patients who achieve a PR and preferably a CR.

Autologous stem cell transplantation

Autologous Stem Cell Transplantation at Disease Relapse

The role of HDT/ASCT has been evaluated in both randomized and nonrandomized trials. To date, ASCT as salvage for HL has been shown to improve EFS, freedom from treatment failure (FFTF), and PFS, but not OS. Two randomized trials comparing ASCT with conventional chemotherapy have been performed and show similar outcomes. In the study by Schmitz and colleagues, 161 patients with relapsed HL were randomly assigned to 4 cycles of Dexa-BEAM or 2 cycles of Dexa-BEAM followed by ASCT. Only patients with chemosensitive disease following 2 cycles of Dexa-BEAM proceeded to SCT. At a median follow-up of 39 months, the study met the primary end point of FFTF for patients with chemosensitive disease (55% for ASCT cohort vs 34% in chemotherapy cohort, P = .019). The British National Lymphoma Investigation performed a prospective study in 40 patients who were randomized to HDT-BEAM followed by ASCT or lower doses of the same regimen (mini-BEAM). This study demonstrated a statistically significant improvement in EFS and PFS ( P = .025 and .005, respectively) favoring ASCT. These findings were further supported by the recently published Cochrane meta-analysis.

Autologous Stem Cell Transplantation in Patients After Induction Therapy for Advanced Hodgkin Lymphoma

The inclusion of HDT/SCT in the initial treatment plan in patients with unfavorable HL who achieved CR with conventional chemotherapy was an attractive idea and an area of initial debate. However, results from randomized studies support that ASCT should not be performed as consolidation in patients with high-risk or advanced HL who have attained a CR to induction treatment. The long-term follow-up of a randomized study of 163 patients with unfavorable HL showed a similar 10-year OS of 85% compared with 84% for patients treated with conventional chemotherapy. Therefore, based on the current data, ASCT cannot be routinely recommended as consolidation after initial therapy in poor-risk patients with chemoresponsive disease.

Autologous Stem Cell Transplantation in Patients with Induction Failure

Several of the retrospective studies of ASCT for HL have included patients with relapsed disease and patients with primary induction failure. There is an apparent benefit in patients with primary induction failure, with reported PFS of 40% to 45% and OS of 30% to 70%. It should be noted that this indication remains controversial, as it is supported only by retrospective data. Furthermore, as noted previously, these data also precede the introduction of newer agents, such as brentuximab vedotin.

Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation

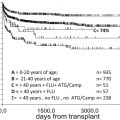

Allogeneic hematopoietic SCT is a potentially curative treatment for patients with relapsed or refractory HL. Initial studies of allo-SCT in patients with HL reported high treatment-related mortality (TRM) and low OS, likely as a result of the use of myeloablative conditioning in a heavily pretreated group of patients. In an analysis of 100 patients performed by the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR), 3-year OS and disease-free survival (DFS) were 21% and 15%, respectively. Similar outcomes were reported by the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT) in a retrospective comparison of myeloablative and reduced-intensity conditioning (RIC). The 5-year OS was 20% in the ablative group and 28% in the RIC group. Patients in the RIC cohort had significantly decreased nonrelapse mortality (NRM) (hazard ratio [HR] 2.85; 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.62–5.02; P <.001) and improved OS (HR 2.05; 95% CI 1.27–3.29; P = .04). There was also a trend for better PFS in the RIC group (HR 1.53; 95% CI 0.97–2.40; P = .07). The data in this retrospective analysis are consistent with improved outcomes and decreased TRM in other prospective and retrospective studies in which patients with HL were transplanted with RIC or nonablative cytoreduction. Although registry data from the CIBMTR reported PFS and OS of 30% and 56% at 1 year, and 20% and 37% at 2 years, respectively, in patients with HL receiving reduced-intensity allo-SCT from unrelated donors, single-institution studies typically report better outcomes. Regarding graft source, a recent systematic review concluded that all stem cell sources, including related and unrelated donors, haploidentical donors, and cord blood, were a reasonable consideration for allo-SCT in patients with HL.

Overall, these studies support the role of graft versus lymphoma (GVL) effect after nonmyeloablative allo-SCT in patients with HL. In particular, a number of studies have documented responses to donor lymphocyte infusions (DLIs). In a study by Peggs and colleagues, the overall response rate (ORR) to DLI for persistent disease or progression in 16 patients was 56% (CR = 8, PR = 1). These results were further supported by a study of the UK Cooperative Group in which the ORR was 79% in 24 patients receiving DLI for relapse (CR = 14, PR = 5). It should be noted that both of these studies used alemtuzumab as part of the conditioning regimen, which results in in vivo T-cell depletion and increased mixed chimerism, for which patients were also given DLI.

Although NRM has decreased with the use of RIC allo-SCT in patients with HL, it does appear to be associated with a higher rate of relapse, although this has not been validated in a prospective randomized study. Nevertheless, relapse remains a significant cause of failure after allo-SCT, and strategies to decrease the risk of relapse, either through preemptive DLI or with the use of post transplant maintenance therapy, as after ASCT, warrant further investigation ( Table 3 ).

| Reference | n | TRM | Relapse | PFS | OS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Myeloablative | |||||

| Anderson et al, 1993 | 53 | 58% (4 y) | 48% (4 y) | 22% (5 y) | 21% (5 y) |

| Gajewski et al, 1996 | 100 | 13% (30 d) 61% (3 y) | 65% (3 y) | 15% (3 y) | 21% (3 y) |

| Milpied et al, 1996 | 45 | 31% (100 d) 48% (4 y) | 61% (4 y) | 15% (4 y) | 25% (4 y) |

| Akpek et al, 2001 | 53 | 32% (100 d) 43% (total) | 53% (10 y) | 26% (10 y) | 30% (10 y) |

| Peniket et al, 2003 | 167 | 52% (4 y) | 65% (5 y) | 16% (4 y) | 25% (4 y) |

| Sureda et al, 2008 | 79 | 28 (3 mo) 46 (1 y) | 30.4% (5 y) | 20% (5 y) | 22% (5 y) |

| Reduced intensity | |||||

| Sureda et al, 2008 | 89 | 15% (3 mo) 23% (1 y) | 57.3% (5 y) | 28% (5 y) | 18% (5 y) |

| Robinson et al, 2009 | 311 | 17% (100 d) 24% (1 y) 27% (2 y) | 48% (1 y) 64% (2 y) | 26% (2 y) | 46% (2 y) |

| Devetten et al, 2009 | 143 | 33% (2 y) | 47% (2 y) | 20% (2 y) | 37% (2 y) |

| Peggs et al, 2005 | 49 | 4% (100 d) 16% (2 y) | 43% | 32% (4 y) | 55% (4 y) |

| Burroughs et al, 2008 | 90 | 200 d | 2 y | 2 y | 2 y |

| RD 38 | 16% | 56% | 23% | 53% | |

| UD 24 | 0 | 63% | 29% | 58% | |

| Haplo 28 | 0 | 40% | 51% | 58% | |

| Alvarez et al, 2006 | 40 | 12% (100 d) 25% (1 y) | NA | 32% (2 y) | 48% (2 y) |

| Anderlini et al, 2005 | 40 | 5% (100 d) 22% (18 mo) | 55% (18 mo) | 32% (18 mo) | 61% (18 mo) |

| Sureda et al, 2012 | 78 | 8% (100 d) 15% (1 y) | 59% (4 y) | 24% (4 y) | 43% (4 y) |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree