Spirituality

Christina M. Puchalski

Palliative care is a specialty based in the whole person care model. Thus, care of the patient and family includes addressing psychosocial and spiritual needs as well as the physical needs. In a whole person-centered model, preservation of human dignity is considered an important part of quality of life. Spiritual care is based in honoring the dignity of each person. In doing so, spiritual care supports the whole person and recognizes that a goal of care is helping each patient find a sense of wholeness and integrity in the midst of suffering and illness. This is especially important in caring for seriously ill and dying patients.

Illness can strip away one’s meaning and purpose, one’s important relationships in life; illness can call into question patients’ beliefs and values thus triggering profound questions of deep meaning purpose and what is most important to a person. It can be an opportunity for deep reflection and growth. Healthcare professionals can hinder that opportunity by not providing attention and space for patients to address these deeper questions in their lives. Illness can also cause deep suffering. Addressing only the physical pain does not address the spiritual and existential suffering seriously ill and dying patients experience. How the healthcare professionals interact with patients in the midst of their illness can have profound effects on how that person will understand their illness, cope with it, find a will to live and persevere, or the strength to let go and die peacefully when it is time. This process, that is, the patients’ confronting their illness and the healthcare system working with the patients to treat that illness, is a spiritual one. Spiritual care is the act of partnering with patients to help them find meaning, wholeness, and healing. Spirituality and spiritual care are the fabrics that underlie the process of honoring the dignity of each person.

THE BIOPSYCHOSOCIAL-SPIRITUAL MODEL

The basic tenets of whole person, patient-centered care are rooted in the biopsychosocial-spiritual model: attention to all the dimensions of a patient—physical, emotional, social, and spiritual (Table 54.1) (1).

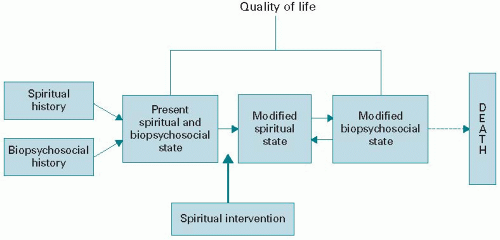

The biopsychosocial care model developed by Engel (2) and White et al. (3) forms another theoretical framework for spiritual care by recognizing that each person is a “being-inrelationship.” In support of extending the biopsychosocial care model to encompass the spiritual, Jonas said, “Life is essentially a relationship; and relation as such implies ‘transcendence,’ a going-beyond-itself on the part of that which entertains the relation” (4). Sulmasy took the association a step farther by describing disease as a disturbance in the right relationships that constitute the unity and integrity of what we know to be a human being (see Fig. 54.1) (5,6).

Spiritual care recognizes that a person’s relationships— from those inside the physical body that define health to external relationships that give a person’s life meaning—are disrupted by illness and, thus, all relationships must be attended to in the treatment or care plan to enhance quality of life.

According to the biopsychosocial-spiritual model, everyone has a spiritual history. For many people, this spiritual history unfolds within the context of an explicit religious tradition; for others it unfolds as a set of philosophical principles or significant experiences. Regardless, this spiritual history helps shape who each patient is as a whole person. An illness experience is unique to each individual in his or her totality (7). This totality includes not only simply the biologic, psychological, and social aspects of the person (8) but also the spiritual aspects as well (9,10). The biologic, psychological, social, and spiritual are distinct dimensions of each person. No one aspect can be disaggregated from the whole. Each aspect can be affected differently by a person’s history and illness and each aspect can interact and affect other aspects of the person (6).

Based on this model, one can reframe the standard assessment and plan to include all dimensions of the person, not just the physical. This radically changes how we approach the patient as person. By attending to the whole person, spiritual care embraces the definition of health as not just absence of disease, but as a state of well-being that includes a sense that life has purpose and meaning (11) as stated in the Pew-Fetzer definition of health: “We are coming to understand health not as the absence of disease, but rather as the process by which individuals maintain their sense of coherence (i.e. sense that life is comprehensible, manageable and meaningful) and ability to function in the face of changes in themselves and their relationship with the environment.”

MEANING AND PURPOSE

Illness and the prospect of dying can call into question the very meaning and purpose of a person’s life. Illness can also cause people to suffer deeply. Victor Frankl wrote that man is not destroyed by suffering; he is destroyed by suffering without meaning (12). Writing about concentration camp victims, he noted that survival itself might depend on seeking and finding meaning. Harold Kushner also noted that pain may be the reason, and out of pain and suffering may come

the answer (13). In my own clinical experience, I have found that people may cope with their suffering by finding meaning in it. Illness can present people with the opportunity to find new meaning in their lives. Many patients say that out of their despair they were able to realize an entirely new and more fulfilling meaning in their lives. Rabbi Cohen wrote,

the answer (13). In my own clinical experience, I have found that people may cope with their suffering by finding meaning in it. Illness can present people with the opportunity to find new meaning in their lives. Many patients say that out of their despair they were able to realize an entirely new and more fulfilling meaning in their lives. Rabbi Cohen wrote,

TABLE 54.1 Dimensions of the dying experience | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

When my mother died, I inherited her needlepoint tapestries. When I was a little boy, I used to sit at her feet as she worked on them. Have you ever seen needlepoint from underneath? All I could see was chaos; strands of thread all over with no seeming purpose. As I grew, I was able to see her work from above. I came to appreciate the patterns, the need for the dark threads as well as the light and gaily colored ones. Life is like that. From our human perspective, we cannot see the whole picture, but we should not despair or feel that there is no purpose. There is meaning and purpose even for the dark threads, but we cannot see that right away (14).

Spirituality helps people find hope in the midst of despair. As caregivers, we need to engage our patients on that spiritual level. This is where spirituality plays such a critical role—the relationship with a transcendent being or concept can give meaning and purpose to people’s lives, to their joys, and to their sufferings. Spirituality is concerned with a transcendental or existential way to live one’s life at a deeper level, “with the person as human being” (15). All people seek meaning and purpose in life; this search may be intensified when someone is facing death.

There are many different ways people can derive meaning from their lives:

Work

Relationships

Hobbies

Art, music, and dance

Reflective writing

Sports

Relationship with God/sacred/Divine

Religious, spiritual, philosophical, or existential beliefs

Religious, spiritual, or cultural rituals

Some of these activities or practices provide an important but perhaps transient meaning (meaning with a small m); others provide a more transcendent and spiritual meaning (meaning with a large M). For example, work may provide an immense amount of meaning to a person. But when that person is ill or dying and unable to work, what then will provide meaning? Therefore, there are activities, relationships, and values that are meaningful but do not define the ultimate purpose of one’s life. Illness, aging, and dying strip away all those things that were meaningful but that do not ultimately sustain us. When we confront ourselves in the nakedness of our dying, it is then that we have the opportunity to find deep and transcendent meaning, that is, values, beliefs, practices, relationships, expressions that lead one to the awareness of transcendence/God/Divine and to a sense of ultimate value and purpose in life. Everyone’s sense of meaning evolves over their life in response to experiences and life in general. People can fluctuate between “meaning” and “Meaning.”

Downey defined spirituality as “an awareness that there are levels of reality not immediately apparent and that there is a quest for personal integration in the face of forces of fragmentation and depersonalization” (16). Spirituality is that aspect of human beings that seeks to heal or be whole. Foglio and Brody wrote,

For many people religion [spirituality] forms a basis of meaning and purpose in life. The profoundly disturbing effects of illness can call into question a person’s purpose in life and work; responsibilities to spouse, children, and parents … Healing, the restoration of wholeness (as opposed to merely technical healing) requires answers to these questions (17).

Healing, then, is not synonymous with recovery. Indeed, healing may occur at any time, independent of recovery from illness. In dying, for example, restoration of wholeness may be manifested by a transcendent set of meaningful experiences while very ill. It may be reflected by a peaceful death. In chronic illness, healing may be experienced as the acceptance of limitations (15). A person may look to medical care to alleviate his or her suffering, and when the medical system fails to do so, begin to look toward spirituality for meaning, purpose, and understanding. As people are faced with serious illness or the prospect of dying, questions often arise:

Why did this happen to me?

What will happen to me after I die?

Why would God allow me to suffer this way?

Will I be remembered?

Will I be missed?

These questions can cause people to undergo a life review whereby they analyze their lives, accomplishments, relationships, and perceived failings (18). This questioning can result in fears, anxieties, and unresolved feelings, which in turn can result in despair and suffering as people face themselves and their eventual mortality. Cassell wrote, “Since in suffering, disruption of the whole person is the dominant theme, we know of the losses and their meaning by what we know of others out of compassion for their suffering” (19). Compassion is essential in the care of all patients, particularly those who are dealing with chronic and serious illnesses and are dying. Two Latin words form the root of the word compassion: “cum,” meaning “with,” and “passio,” meaning “suffering with” (20). What compassionate care asks us to do is to suffer with our patients, that is, to be present to them fully as they suffer and to partner with them in the midst of their pain.

SPIRITUALITY IN CLINICAL PRACTICE PROFESSIONAL GUIDELINES

Guidelines from several organizations, including the American College of Physicians (ACP) and The Joint Commission on Healthcare Accreditation, American Association of Nursing, and National Association of Social Workers, recognize the need for spiritual care. In a recent ACP consensus conference on end of life, it was concluded that physicians have the obligation to address all dimensions of suffering, including spiritual, religious, and existential suffering (21). It also developed guidelines for communicating with patients about spiritual and religious matters (22). JCAHO (Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations) requires that spiritual care be available to patients in hospital settings (23). In 1978, the first nursing diagnosis related to spirituality, spiritual distress, was established in the North American Nursing Diagnosis Association (NANDA). Spiritual distress is the “impaired ability to experience and integrate meaning and purpose in life through a person’s connectedness with self, others, art, music, literature, nature, or a power greater than oneself” (24). The Code of Ethics for professional nurses in the United States recognizes the importance of spirituality and health, illustrated by Provision 1 of the code, which states, “The nurse, in all professional relationships, practices with compassion and respect for the inherent dignity, worth, and uniqueness of each individual, unrestricted by considerations of social and economic status, personal attributes, or the nature of health problems” (25). The National Association of Social Workers’ Code of Ethics declares that a social worker must include spirituality when completing an assessment (26).

The National Quality Forum identified spiritual care as one of eight domains of the Clinical Practice Guidelines developed by the National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care (NCP) (27). The NCP is a coalition of the leading palliative care organizations in the United States. The NCP recommendations for spiritual care emphasize regular and ongoing assessment and response to patients’ spiritual and existential issues and concerns. They emphasize the use of a spiritual assessment to identify religious or spiritual/existential preferences, beliefs, rituals, and practices of the patient and family. These guidelines also recognize the need for inclusion of pastoral care in the interdisciplinary care team.

DATA DEMONSTRATING PATIENT NEED

Studies, as well as theoretical and philosophical literature, demonstrate the impact of religious and spiritual beliefs on people’s moral decision-making, way of life, ability to transcend suffering, dealing with life’s challenges, interactions with others, and life choices. Spiritual and religious beliefs have been shown to have an impact on how people cope with serious illness, aging, and life stresses. Spiritual practices can foster coping resources (28,29), promote health-related behavior (30), enhance a sense of well-being and improve quality of life (31), provide social support (32), and generate feelings of love and forgiveness (33). Spiritual beliefs can also impact healthcare decision-making (34). Spiritual/religious beliefs, however, can also be harmful (35). Thus, spirituality may be a critical dynamic of how patients understand their illness and cope with it either positively or negatively.

Research also indicates that patients would like their spiritual beliefs addressed by physicians and other healthcare professionals in a variety of healthcare circumstances (36).

One study shows that patients feel increased trust in their clinicians if a spiritual history is obtained. They also note that they experience an increased sense of being listened to (36). Interestingly, a study by Balboni et al. showed that 75% of dying cancer patients did not have their spiritual needs met even when 95% of them said spirituality was important to them (37). These data indicate the importance of developing guidelines and resources for patients and clinicians.

One study shows that patients feel increased trust in their clinicians if a spiritual history is obtained. They also note that they experience an increased sense of being listened to (36). Interestingly, a study by Balboni et al. showed that 75% of dying cancer patients did not have their spiritual needs met even when 95% of them said spirituality was important to them (37). These data indicate the importance of developing guidelines and resources for patients and clinicians.

RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN SPIRITUALITY AND COPING

The beneficial effects of spirituality in helping people cope with serious illness and dying are well documented (38). Furthermore, researchers have noted that most patients with cancer in a palliative care setting experience spiritual pain, which is expressed as an internal conflict, a loss or interpersonal conflict, or in relation to God/Divine. Fitchett et al. have shown that spiritual struggles are associated with poor physical outcome and higher rates of morbidity (39). Spiritual pain is also related to psychological distress so that patients presenting with depression or anxiety may actually be suffering from spiritual conflict (40).

Quality of life instruments used in end-of-life care try to measure an existential domain, which addresses purpose, meaning in life, and capacity for self-transcendence. In studies of one such instrument, three items have been found to correlate with good quality of life for patients with advanced disease: if the patient’s personal existence is meaningful; if the patient finds fulfillment in achieving life goals; and if life to this point has been meaningful (41). This supports the importance of addressing meaning and purpose in a dying person’s life. Spirituality and nonorganized religion have also been associated positively with the will to live in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (HIV) (42).

The observations noted in patient stories (15) and in the writings of Foglio and Brody (17)—that illness can cause people to question their lives, their identities, and what gives their life meaning—are supported by research. For example, in a study of 108 women undergoing treatment for gynecologic cancer, 49% noted becoming more spiritual after their diagnosis (29). In a study of parents with a child who had died of cancer, 40% of those parents reported a strengthening of their own spiritual commitment over the course of the year before their child’s death (43). Illness, facing one’s mortality, is an opportunity for new experience, self-awareness, and meaning in life.

Religion and religious beliefs can play an important role in how patients understand their illness. In a study asking older adults about God’s role in health and illness, many respondents saw health and illness as being partly attributable to God and, to some extent, God’s interventions (44). Pargament et al. have studied both positive and negative coping and have found that religious experiences and practices, such as seeking God’s help or having a vision of God, extend the individual’s coping resources and are associated with improvement in healthcare outcomes (45). Patients showed less psychological distress if they sought control through a partnership with God or a higher power in a problem-solving way, if they asked God’s forgiveness or were able to forgive others, if they reported finding strength and comfort from their spiritual beliefs, and if they found support in a spiritual community. Patients had more depression, poorer quality of life, and callousness toward others if they saw the crisis as a punishment from God, if they had excessive guilt, or if they had an absolute belief in prayer and cure and an inability to resolve their anger if cure did not occur. Pargament et al. have also noted that sometimes patients refuse medical treatment based on religious beliefs (35).

There are a number of studies on meditation as well as other spiritual and religious practices that demonstrate a positive physical response, especially in relation to levels of stress hormones and modulation of the stress response (46). Although more solid evidence is needed, there appears to be an association between meditation and some spiritual or religious practices and certain physiologic processes, including cardiovascular, neuroendocrine, and immune function.

SPIRITUAL COPING

How does spirituality work to help people cope with their dying (Table 54.2)? One mechanism might be through hope. Hope is a powerful inner strength that helps one transcend the present situation and helps foster a positive belief or outlook. Spirituality and religion offer people hope and help people find hope in the midst of the despair that often occurs in the course of serious illness and dying. Hope can change during a course of an illness. Early on, the person may hope for a cure; later, when a cure becomes unlikely, the person may hope for time to finish important projects or goals, travel, make peace with loved ones or with God, and have a peaceful death. This can result in a healing, which can be manifested as a restoration of one’s relationships or sense of self. Often our society thinks in terms of cures. Whereas cures may not always be possible, healing—the restoration of wholeness—may be possible to the very end of life. Hope has also been shown to be an effective coping mechanism. Patients who are more hopeful tend to be less depressed.

Religious beliefs offer a sense of hope. For example, in Catholicism, hope in Jesus’ promise of victory over death through resurrection and salvation gives Catholics hope in a

life beyond death. In the funeral rites, it is stated, “I believe in the resurrection of the dead and the life of the world to come” (47). In the Protestant view, the concept of salvation in death gives hope. Jesus’ dying and rising from the dead means that those who participate in His death no longer participate in the sinful human nature (48). In Eastern traditions such as Buddhism and Hinduism, the hope of rebirth and a belief in karma offer people hope in the face of mortality (49). In Judaism, there are many diverse ways of viewing death. For some, hope is found in living on through one’s children. In the orthodox and conservative views, there is a belief in a resurrection in which the body arises to be united with the soul (50). For patients with and without specific religious beliefs, there is a need to transcend death, which may also be manifested through living on through one’s relationships or one’s accomplishments and deeds (51). Irion suggests that humans may create abstractions by portraying a life after death (52). For the religious, this may take the form of concepts found in their religious traditions. For others, life after death might be in terms of one’s descendants. For some, it might be being immortalized in the memory of others or in the contributions one makes in life. Cultural beliefs and traditions can also contribute to how people find meaning and hope in the midst of despair (53).

life beyond death. In the funeral rites, it is stated, “I believe in the resurrection of the dead and the life of the world to come” (47). In the Protestant view, the concept of salvation in death gives hope. Jesus’ dying and rising from the dead means that those who participate in His death no longer participate in the sinful human nature (48). In Eastern traditions such as Buddhism and Hinduism, the hope of rebirth and a belief in karma offer people hope in the face of mortality (49). In Judaism, there are many diverse ways of viewing death. For some, hope is found in living on through one’s children. In the orthodox and conservative views, there is a belief in a resurrection in which the body arises to be united with the soul (50). For patients with and without specific religious beliefs, there is a need to transcend death, which may also be manifested through living on through one’s relationships or one’s accomplishments and deeds (51). Irion suggests that humans may create abstractions by portraying a life after death (52). For the religious, this may take the form of concepts found in their religious traditions. For others, life after death might be in terms of one’s descendants. For some, it might be being immortalized in the memory of others or in the contributions one makes in life. Cultural beliefs and traditions can also contribute to how people find meaning and hope in the midst of despair (53).

TABLE 54.2 Spiritual coping | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Finding meaning in the midst of suffering and uncertainty is critical to effective coping. Spiritual beliefs in general and religious, in particular, can help people find this meaning and purpose. Religion provides a system of beliefs, ritual, and community that can help people find meaning in the context of their illness and dying (54). One very powerful intervention that addresses meaning with patients with advanced cancer has had positive outcomes in these patients. It involved a brief meaning-centered group psychotherapy intervention that is centered on helping patients find meaning in the midst of their suffering (55).

Spirituality can offer people a sense of control. Illness can disrupt life completely. Some people find a sense of control by turning worries or a situation over to a higher power or to God (56). Similarly, people can use their beliefs to help them accept their illness and find strength to deal with their situation (57). Reconciliation may be an important aspect of a dying person’s spiritual journey. Often people seek to forgive others or themselves as they review their lives and their relationships.

SPIRITUAL ISSUES: DIAGNOSIS AND RESOURCES OF STRENGTH

The diagnosis of chronic or life-threatening illness or other adverse life events can lead to spiritual struggles for patients. The turmoil may be short for some patients and protracted for others as individuals attempt to integrate the reality of their diagnosis with their spiritual beliefs. The journey may result in growth and transformation for some people and to distress and despair for others (58).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree