As patients are living longer and axial imaging is more widespread, increasing numbers of cystic neoplasms of the pancreas are found. Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms and mucinous cystic neoplasms are the most common. The revised Sendai guidelines provide a safe algorithm for expectant management of certain cystic neoplasms; however, studies are ongoing to identify further subgroups that can be treated nonoperatively. For those patients with high-risk clinical features or symptoms, surgical resection can be performed safely at high-volume pancreatic centers. Accurate diagnosis is critical for accurate decision making.

Key points

- •

Cystic neoplasms of the pancreas are an increasingly recognized clinical entity, now in up to 10% of patients older than 70 years.

- •

Management of these lesions, particularly intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm, remains controversial.

- •

Many of these neoplasms can be managed safely with surgical resection at high-volume pancreatic centers, whereas an increasing number of subgroups may be watched safely. Accurate diagnosis is paramount.

- •

The revised Sendai guidelines seem to provide a safe framework for management of mucinous cystic neoplasm and intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm.

- •

Ongoing research will likely better stratify the underlying risk of invasive cancers in these patients.

Introduction

The incidental finding of pancreatic cysts creates significant concern for the clinician given the grave prognosis for patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC). The increasing use of axial imaging has contributed to the surge in the diagnosis of pancreatic cystic lesions. In asymptomatic patients, up to 2.5% are found to have pancreatic cysts, a number that increases to 10% in patients older than 70 years. Fortunately, more sophisticated understanding of these clinical entities has allowed for more nuanced management in recent years, which has obviated many unnecessary and morbid operations. However, despite our improved understanding of pancreatic cysts, there is still ongoing debate regarding management of these lesions. We aim to provide a guide to the diagnosis and management of cystic neoplasms of the pancreas (CNPs).

For cystic lesions of the pancreas, there is a spectrum from benign to malignant. Benign entities include pancreatic pseudocysts, infectious cystic lesions of the pancreas, congenital cysts, pancreatic duplication cysts, retention cysts, and lymphoepithelial cysts. There are several rare nonepithelial neoplasms, including lymphangiomas, epidermoid cysts in an intrapancreatic spleen, cystic pancreatic hamartomas, and mesothelial cysts. Of the epithelial neoplasms, the most common are mucinous cystic neoplasms (MCNs), serous cystic neoplasms (SCNs), cystic pancreatic endocrine neoplasms (CPENs), solid pseudopapillary neoplasms (SPNs), and intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMNs). These 5 clinical entities are discussed in this review. Another notable cystic neoplasm is a PDAC with cystic degeneration, but this comprises less than 1% of resected specimens and is not discussed here. Overall, the number of invasive cancers in this epithelial group of cystic neoplasms has significantly declined over the last 40 years, from 41% in the 1970s and 1980s to 12% in the 2000s, consistent with earlier diagnosis and treatment of incidentally discovered and presumably premalignant lesions. It is predicted that this number will continue to decline as our diagnostic capabilities improve.

Introduction

The incidental finding of pancreatic cysts creates significant concern for the clinician given the grave prognosis for patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC). The increasing use of axial imaging has contributed to the surge in the diagnosis of pancreatic cystic lesions. In asymptomatic patients, up to 2.5% are found to have pancreatic cysts, a number that increases to 10% in patients older than 70 years. Fortunately, more sophisticated understanding of these clinical entities has allowed for more nuanced management in recent years, which has obviated many unnecessary and morbid operations. However, despite our improved understanding of pancreatic cysts, there is still ongoing debate regarding management of these lesions. We aim to provide a guide to the diagnosis and management of cystic neoplasms of the pancreas (CNPs).

For cystic lesions of the pancreas, there is a spectrum from benign to malignant. Benign entities include pancreatic pseudocysts, infectious cystic lesions of the pancreas, congenital cysts, pancreatic duplication cysts, retention cysts, and lymphoepithelial cysts. There are several rare nonepithelial neoplasms, including lymphangiomas, epidermoid cysts in an intrapancreatic spleen, cystic pancreatic hamartomas, and mesothelial cysts. Of the epithelial neoplasms, the most common are mucinous cystic neoplasms (MCNs), serous cystic neoplasms (SCNs), cystic pancreatic endocrine neoplasms (CPENs), solid pseudopapillary neoplasms (SPNs), and intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMNs). These 5 clinical entities are discussed in this review. Another notable cystic neoplasm is a PDAC with cystic degeneration, but this comprises less than 1% of resected specimens and is not discussed here. Overall, the number of invasive cancers in this epithelial group of cystic neoplasms has significantly declined over the last 40 years, from 41% in the 1970s and 1980s to 12% in the 2000s, consistent with earlier diagnosis and treatment of incidentally discovered and presumably premalignant lesions. It is predicted that this number will continue to decline as our diagnostic capabilities improve.

Mucinous cystic neoplasms

Introduction

MCNs make up approximately 23% of the resected cystic tumors of the pancreas. To make the diagnosis of an MCN, the cyst must contain ovarian-type stroma. MCNs occur almost exclusively in women, as solitary lesions in the body or tail of the pancreas. The median age of diagnosis is mid-to-late 40s. Given the risk of invasive disease, current guidelines recommend resection for all patients with MCN who are fit enough to undergo an operation.

Clinical Presentation

Many of the patients with an MCN are symptomatic at the time of presentation, with nonspecific abdominal pain as the most common symptom. Other less-common symptoms include fatigue, weight loss, abdominal mass, and pancreatitis, and jaundice is exceedingly rare. The remaining MCNs are found incidentally on imaging or on final pathology. The mean size at resection in our series of 199 patients was 4.4 cm.

Pathophysiology

The mechanism of MCN development remains under investigation. Recent reports implicate the KRAS pathway and the canonical Wnt pathway. Activation of the canonical Wnt pathway promotes development of the pathognomonic ovarianlike stroma in a mouse model of MCN.

Pathology/Classification

The histologic hallmark of MCN is an inner epithelial layer, consisting of mucin-secreting cuboidal epithelium, and an outer layer of ovarianlike stroma. The cysts often lack a connection to the duct. There is a spectrum of disease from benign (mucinous cystadenoma) to malignant (mucinous cystadenocarcinoma), with invasive carcinoma present in 5% to 16% of MCNs. Factors associated with a higher likelihood of invasive carcinoma include the presence of greater than 1 cm intracystic papillary nodules, increased size (>3 cm), and increased serum CA19-9 level. Additional studies have posited that age itself is a risk factor for malignant versus benign MCN.

Diagnosis

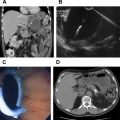

The diagnosis of MCN is made by confirmation of the aforementioned histologic characteristics. Suggestive radiologic features include a solitary cyst with thick walls, septations, calcifications, and mural nodules. The presence of these findings in a middle-age woman is highly suggestive of MCN. MCNs are most often found in the body or tail of the pancreas. endoscopic ultrasound scan (EUS) can be performed and a high carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) level in the cyst fluid aspirate is expected for mucinous lesions.

Management

Given the risk of malignant disease, definitive surgical management is the current standard of care for all suspected MCNs. Some investigators advocate for a watchful waiting approach, whereas others suggest that smaller lesions (<4-cm tumors without nodules) do not require a radical resection. This approach is similar to the approach advocated by the Sendai Consensus guidelines for brand duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (BD-IPMN). Patients whose benign, noninvasive MCN has been resected have an excellent survival rate, whereas once invasive or malignant tumors have developed, the 5-year survival rate decreases dramatically, ranging from 0% to 75% in various studies.

Serous cystic neoplasm

Introduction

Serous cystadenomas or SCNs are benign cystic tumors of the pancreas and represent approximately 16% of resected pancreatic cystic neoplasms. These tumors occur more frequently in women (75%) at a mean age of 50 to 60 years. Rare case reports document serous cystadenocarcinomas. SCNs grow slowly, and most are found incidentally on imaging. Operative intervention is reserved for symptomatic patients.

Clinical Presentation

In most large series, patients present with symptoms. Abdominal pain is the most common presenting symptom, with fullness/palpable mass. Jaundice and diabetes are seen less frequently. Mean size at presentation is variable, ranging from 2.9 to 5.1 cm.

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of SCNs is unknown, although some sporadic SCNs are found to have modifications of the VHL-related genes. Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome is a known risk factor for SCN.

Pathology/Classification

SCNs are benign, slow-growing cystic lesions without predilection for a particular part of the pancreas. They are classically described as having many tiny glycogen-rich cysts, a cuboidal epithelial lining resembling a honeycomb, and a central scar. A recent classification of 4 variants has been proposed: microcystic, macrocystic, mixed, and solid. The cutoff between microcystic and macrocystic is 2 cm for the dominant cyst. A mixed type contains elements of both. Microcystic is the most common variant (45%), followed by macrocystic (32%), mixed (18%), and solid (5%). There are rare cases of malignant SCNs, serous cystadenocarcinoma, with 28 published cases since 1989. Of the 3 patients in a series of 2622, 2 had hepatic metastases and 1 had a positive portal lymph node. These tumors tended to be large (7.1–17 cm) and all were symptomatic. In the same study, of the 1590 patients undergoing resection, 18 tumors were locally aggressive, based on the definition from the Hopkins group. Most common sites of invasion were the peripancreatic vessels (8 of 18) and regional organs (6 of 18).

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of SCN is often made by radiologic appearance. The classic appearance of a microcystic SCN is of a honeycomb that is multilobular with central calcifications or scar in 16% to 26%. The diagnosis is more difficult in oligocystic or solid variants, as these appear similar to MCN or branch duct IPMN. EUS with fluid analysis can be performed but may be difficult in microcystic disease. These nonmucinous cysts typically have low CEA levels in the cyst fluid.

Management

The largest multicenter series found only 3 serous adenocarcinomas of 2622 patients, confirming the benign natural history of this entity. As such, symptoms remain the cardinal indication for operation. The growth rate is 4 to 6 mm/y, with increased rates of growth after 7 years of observation or in tumors 4 cm. Given the variability of the data regarding size and symptoms, it seems that symptoms are paramount in determining the necessity of an intervention. It would logically follow that a younger patient will likely undergo resection at some point, and it may be wise to intervene before the procedure becomes more difficult. Lastly, diagnostic certainty must be in place before a trial of watchful waiting is undertaken, which is more difficult to obtain in cases of the oligocystic variant. In the aforementioned large retrospective series, over the course of 26 years, 61% of all patients eventually underwent resection with less than 1% perioperative or disease-specific mortality.

Cystic pancreatic endocrine neoplasms

Introduction

CPENs are an uncommon variant of solid pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (PNET) and account for 7% of all resected cystic pancreatic neoplasms and 12% to 17% of all resected PNETs. For many years, CPENs were considered similar in behavior to their solid counterparts, but more recent series suggest a difference in presentation and biology. CPENs are divided equally by sex and have a slight predilection for the body or tail of the pancreas. Mean age at presentation is in the 50s. Current recommendations are for surgical resection given the risk of invasive cancer.

Clinical Presentation

Symptoms are present in 32% to 73% of patients. The most common symptoms are abdominal and back pain, whereas less common symptoms are weight loss, anemia, weakness, palpable mass, and pancreatitis. CPENs are more likely to be nonfunctional compared with solid PNETs (80% vs 50%), with 67% of functional CPENs being insulinomas. These tumors tended to be larger than PNETs, with a mean size of 4.9 cm versus 2.4 cm, however, in another series, CPENs were smaller than other cystic pancreatic neoplasms (2.1 cm vs 3.0 cm). Perhaps this difference in size at presentation explains the lower incidence of symptoms at presentation in the latter study (32% vs 73%).

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of CPENs remains unknown, although several series show a significant association with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1, an autosomal dominant genetic disorder associated with parathyroid hyperplasia, endocrine tumors of the pancreas, pituitary adenomas, and carcinoid tumors.

Pathology/Classification

CPENs can be described as either purely cystic (34%) or partially cystic (66%). CPENs classically have prominent septations. The cystic nature of these tumors was thought to be from degeneration of solid PNET, but on pathologic examination, necrosis is uncommon. The diagnosis is made with immunohistochemical staining for synaptophysin (100%), chromogranin A (82%), pancreatic polypeptide (74%), and glucagon (>50%). In terms of biologic activity, nearly all CPENs had low mitotic rates, although the rate of metastasis was similar to that of solid PNETs (7.8% vs 10%). CK19, a marker of aggressive behavior in PNET, was present in only 24% of cases of CPEN.

Diagnosis

The appearance on imaging is variable, with many showing prominent septations and arterial enhancement. The Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) series found that an accurate preoperative diagnosis was only made in 23% of patients but increased to 71% if preoperative cytology was used. Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center reported a 61% accuracy based on preoperative studies, including cytologic evaluation. Cyst aspiration classically finds a low cyst CEA level.

Management

The risk of aggressive biology or metastatic disease is variable, anywhere from 0% to 14%. As such, the current recommendation is for surgical resection. The 5-year outcomes are excellent, with survival rates in excess of 87%, which is not statistically significantly different from those of PNETs of the same size.

Solid pseudopapillary neoplasm

Introduction

SPNs are the most rare of the 5 major types of cystic neoplasms of the pancreas, making up just 3% of resected specimens. SPN is a tumor of young women, with the mean age at presentation in the fourth decade of life. SPNs are most commonly found in the tail of the pancreas. Given the potential for advanced or metastatic disease, surgical resection remains the recommended treatment modality.

Clinical Presentation

Most patients are symptomatic (84%–87%), with abdominal pain being the most common symptom (84%). Other symptoms include nausea/vomiting (19%), pancreatitis (10%), and weight loss (10%). Jaundice is variably reported. The median size at the time of resection is 4.5 to 4.9 cm.

Pathophysiology

The adenomatous polyposis coli/β-catenin pathway has been implicated in the pathophysiology of SPN, whereas K-ras mutations and DPC4 inactivation were uniformly absent. The exact mechanism is unknown.

Pathology/Classification

SPNs are on a spectrum from mostly solid to mostly cystic. SPNs are easily distinguishable from surrounding tissue and can have hemorrhage present. Histologically, there are uniform discohesive polygonal cells that envelop small blood vessels. Approximately 10% to 20% of these patients have locoregional spread, often to the lymph nodes, with some patients having direct invasion of the superior mesenteric artery, portal vein, or duodenum. There are rare cases of liver metastases or otherwise widely metastatic disease. Tumor size is found to correlate with aggressive behavior.

Diagnosis

Computed tomography findings are consistent with the pathologic spectrum from mostly solid to mostly cystic, with peripheral arterial enhancement and central calcification in 16% of lesions. EUS/fine-needle aspiration may be helpful, but the diagnosis was only made in 62% of patients undergoing cytologic analysis. In a series of both transperitoneal and endoscopic biopsy techniques, preoperative diagnosis was only made 56% of the time. Cytology results often show necrotic cells, and CEA level is low on fluid analysis.

Management

Given the high frequency of symptoms and the 10% to 20% risk of aggressive biology, the treatment is principally surgical. There are rare recurrences after operative intervention, which are treated with either an operation or systemic chemotherapy, or both. Despite the risk of malignancy and locoregional spread, most patients do well, and the long-term survival rate is excellent, well in excess of 80% to 90%.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree