Specimen Processing, Evaluation, and Reporting

A variety of breast specimen types are encountered by the surgical pathologist in daily practice. Appropriate processing and evaluation of these specimens is necessary in order to obtain the maximum clinically relevant information.

CORE-NEEDLE BIOPSIES

Core-needle biopsy (CNB) using image-directed guidance methods, such as stereotactic mammography, ultrasound, and magnetic resonance imaging, has become the method of choice for the initial evaluation of non-palpable lesions at many institutions.1, 2 and 3 CNB, sometimes with ultrasound guidance, may also be used to sample palpable lesions. Some CNB devices are spring-loaded and fire a cutting needle into the breast tissue. Others employ vacuum assistance following needle insertion to draw tissue into the cutting chamber and to facilitate sample collection. For any given needle size, the use of vacuum-assisted devices results in substantially larger specimens than spring-loaded devices. Another advantage of vacuum-assisted devices is that they permit the collection of numerous, contiguous samples with a single needle insertion in contrast to the multiple insertions required to obtain samples using spring-loaded devices. At many institutions, vacuum-assisted devices are used to sample microcalcifications, whereas spring-loaded devices are used to sample mass lesions.

A newer, percutaneous approach utilizes a 15- or 20-mm vacuum- and radiofrequency-assisted device that removes a mammographically targeted lesion in a single, intact specimen. In contrast to the fragmented specimens obtained by CNB, this method permits evaluation of the entire lesion intact and enables assessment of excision margins.4 However, the role of this technique in clinical practice remains to be determined.

If the indication for CNB is mammographic microcalcifications, a specimen radiograph should be obtained by the radiologist and the coreneedle samples with the calcifications submitted separately from those without calcifications in order to identify for the pathologist the cores of greatest concern. The pathology requisition that accompanies the specimen should indicate at a minimum the laterality and location in the breast from where the CNB specimens were obtained, the indication for biopsy (i.e., mass, microcalcifications, architectural distortion), the image guidance method, and the size of the needle used.

CNB specimens should be submitted in their entirety for microscopic evaluation. While there is no universal agreement about the number of levels that should be cut from blocks of CNB specimens, a sufficient number of levels should be cut to permit as complete a pathologic-radiographic correlation as possible in every case. We routinely cut three levels from each block for initial evaluation. If the findings on the initial histologic sections do not account for the findings on the imaging studies, every attempt should be made to resolve the discrepancy. Examples of common discrepancies and their possible resolutions are listed in Table 20.1. However, not all discrepancies can be resolved by further pathologic evaluation of the CNB specimen and if this occurs, it should be noted in the final pathology report. For example, if the indication for CNB is a mass lesion and the CNB samples reveal only unremarkable breast tissue after multiple levels are examined, the final report should indicate that histologic findings of a mass-forming lesion are not identified and that clinical and radiographic correlation are advised. Regularly scheduled radiology-pathology correlation conferences are of great value to discuss cases with radiologic-pathologic discordance and to formulate a plan to resolve such discrepancies.

TABLE 20.1 Common Pathologic-Radiologic Discrepancies in Core-Needle Biopsies and Their Possible Resolutions | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Immunohistochemical evaluation for hormone receptors, HER2, and other biomarkers can be performed on CNB specimens, and the results generally correlate well with those on subsequent excision specimens.5, 6, 7 and 8 In fact, the results of one study suggested that estrogen receptor (ER) and progesterone receptor (PR) assays are more reliable on CNB specimens than on excision specimens.7 Assessing these biomarkers on CNB samples is particularly important for clinical decision making in patients with breast cancer who will be treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy. We routinely perform ER, PR, and HER2 assays on CNB specimens containing invasive breast cancers and ER on those that show ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS).9

INCISIONAL BIOPSIES

Incisional biopsies of breast masses are rarely performed in current clinical practice, but if received, these should be submitted completely for histopathologic examination. As for CNB specimens, these specimens are suitable for the evaluation of hormone receptor status, HER2, and other biomarkers.

EXCISIONAL BIOPSY (LUMPECTOMY, PARTIAL MASTECTOMY) PERFORMED FOR A PALPABLE MASS

Careful macroscopic examination of excisional biopsy specimens is an essential component of their evaluation. Every breast excision should be measured in three dimensions. The palpable lesion should also be measured in three dimensions and its relationship to the overlying skin or underlying fascia or skeletal muscle, if present, should be noted. The distance between any macroscopically evident tumor and the margins of excision should also be recorded.

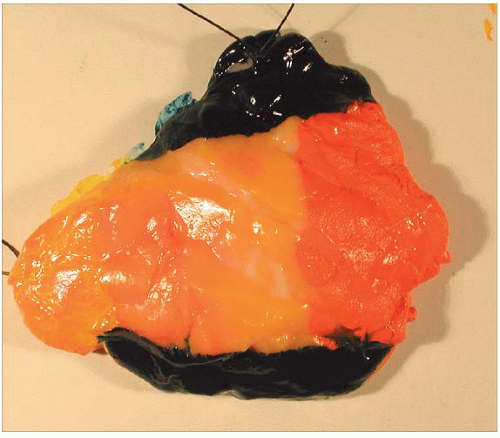

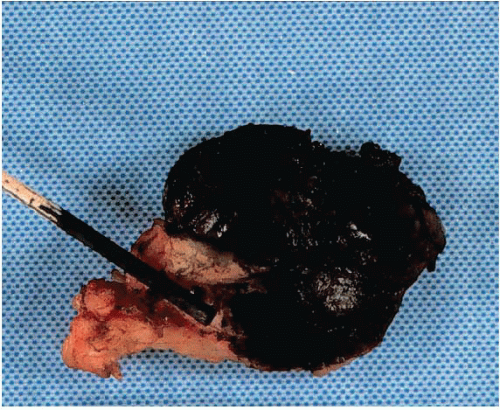

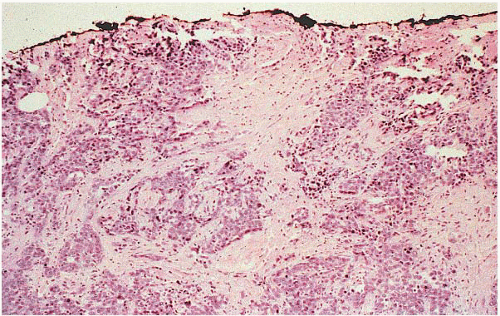

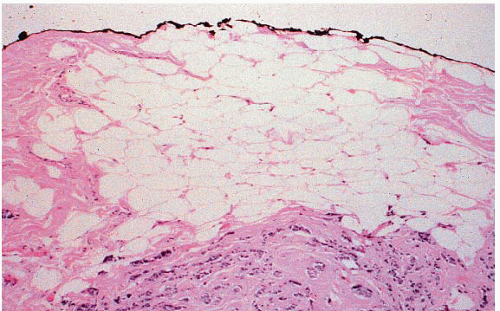

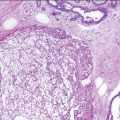

If the specimen has been oriented by the surgeon, the margins should be inked in six colors prior to sectioning to retain orientation and to permit the identification of specific margins (superficial/anterior, deep/posterior, medial, lateral, superior, and inferior) on histopathologic examination (Fig. 20.1). Unoriented specimens should be inked in a single color (Fig. 20.2). Following inking, the specimen should be sectioned through the equatorial plane (“breadloafed”). Unfortunately, even with careful attention to technical details, ink commonly seeps into the specimen and this in turn may create difficulties in the histologic evaluation of the margins (Fig. 20.3). The seepage of ink can be minimized by blotting the specimen surface before and after application of ink and then immersing the specimen briefly in Bouin solution, which serves to mordant the ink. When this method of margin evaluation is used for cases with DCIS or invasive cancer, a margin is considered positive when the lesion of concern is present at the inked tissue edge (Fig. 20.4, e-Fig. 20.1). There is no universal agreement among pathologists or clinicians as to what distance between the inked tissue edge and the tumor cells constitutes an adequate negative margin.10, 11 and 12 Further, the optimal margin width varies with the clinical situation. For example, a wider margin is more desirable for a patient with DCIS who will be treated by excision alone than for a patient with invasive breast cancer who will be treated by excision, radiation therapy, and systemic therapy. Therefore, subjective, judgmental terms such as “close” and “negative” should be avoided in pathology reports. In our practice, if the lesion is not at the inked tissue edge, we report the closest distance of the lesion to the nearest inked margin(s) in millimeters or fractions thereof (Fig. 20.5).

FIGURE 20.3 Ink commonly tracks into the substance of the specimen. In some cases, this makes it difficult to identify the true margin of excision on histologic evaluation. |

An alternative method of margin evaluation consists of shaving off some or all of the surface of the specimen and submitting these tangentially obtained (en face) sections for histological examination. Although this method affords sampling of a greater surface area of the specimen, the shaved margin method may result in patients categorized as having positive margins when, in fact, there is no cancer at the inked surface of the specimen (false positives), and this in turn may result in unnecessary further surgery or even mastectomy in a patient who may be a suitable candidate for breast-conserving treatment.13 In some instances, the surgeon may remove arcs of additional tissue from the walls of the biopsy cavity immediately after the lumpectomy specimen has been excised and submit these specimens to the pathologist individually as separate margins.14 The surgeon should ideally mark with a suture the side of the specimen that represents the final margin so that surface can be inked and assessed microscopically.

Arguably the most accurate way to evaluate margins of breast excision specimens is with whole mount or large format sections with or without three-dimensional reconstruction.15 However, the prolonged processing time and special equipment, supplies, and slide storage requirements for whole mount sections make this approach impractical at most centers.

Some authors have advocated the use of frozen sections or touch imprints for the intraoperative evaluation of breast excision margins.16,17 The theoretical advantage of this approach is that it could reduce the need

for a second surgical procedure in patients with positive margins in the initial excision specimen. However, cutting and interpretation of frozen sections of breast specimen margins are often problematic. In addition, when intraoperative margin evaluation is used, the decision to perform additional breast surgery is unifactorial and depends solely on the status of the margins determined intraoperatively. In clinical practice, at most institutions, the need for further surgery is based on consideration of multiple factors in addition to the status of the margins, including the specific margin involved, the extent of margin involvement, the presence of an extensive intraductal component, the status of the axillary lymph nodes, the use of systemic therapy, the competing risk of distant recurrence, tumor size relative to breast size, and the patient’s desire for breast conservation. Further, even with the use of intraoperative margin evaluation, positive final margins are seen in 20% to 25% of cases.16 Therefore, the rationale for routinely performing intraoperative margin assessment can be questioned.18

for a second surgical procedure in patients with positive margins in the initial excision specimen. However, cutting and interpretation of frozen sections of breast specimen margins are often problematic. In addition, when intraoperative margin evaluation is used, the decision to perform additional breast surgery is unifactorial and depends solely on the status of the margins determined intraoperatively. In clinical practice, at most institutions, the need for further surgery is based on consideration of multiple factors in addition to the status of the margins, including the specific margin involved, the extent of margin involvement, the presence of an extensive intraductal component, the status of the axillary lymph nodes, the use of systemic therapy, the competing risk of distant recurrence, tumor size relative to breast size, and the patient’s desire for breast conservation. Further, even with the use of intraoperative margin evaluation, positive final margins are seen in 20% to 25% of cases.16 Therefore, the rationale for routinely performing intraoperative margin assessment can be questioned.18

NEEDLE (WIRE) LOCALIZATION EXCISIONS FOR NON-PALPABLE LESIONS

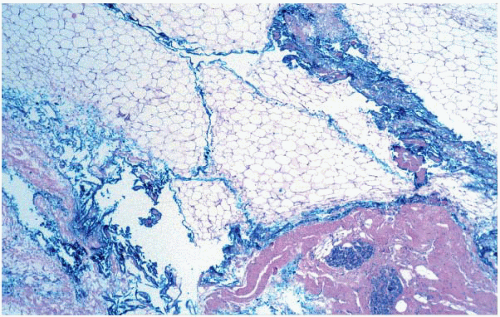

The needle or wire localization technique is used to guide the surgeon to the area of mammographic abnormality or to the site of a prior CNB for non-palpable lesions. The most frequent mammographic abnormalities prompting biopsy are microcalcifications, a soft tissue density, or a combination of the two. Specimen radiography is crucial in the evaluation of these specimens in order to document the presence of the lesion detected by mammography and/or the radiopaque clip or marker placed at the site of a prior CNB and to localize the targeted area for histologic examination (Fig. 20.6

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree