Chapter 3

Special skills in geriatric emergency medicine

Geriatric Emergency Medicine presents multiple clinical and ethical challenges. These challenges require the clinician to have distinct areas of skills and knowledge including assessment and treatment of pain, assessment of decision-making capacity, palliative and end-of-life care in the emergency department and discussion of resuscitation, escalation and intensive care treatment.

Owing to the differences in healthcare systems globally, local and national guidance should be sought when confronted with ethical and legal issues in acute geriatric care.

Pain in the older patient

Older patients commonly present with acute or chronic pain to the ED. Despite this, pain in older patients is often under-recognised and undertreated. Older adults are 20% less likely to receive treatment for pain than younger patients (1). There is often a delay to administration of analgesia (2). Regardless of the underlying cause, effective treatment of acute pain is important for relieving suffering, enabling early mobilisation and preventing delirium and chronic pain. Pain should be considered a fundamental part of the initial assessment.

Optimal pain management is made more complex by reduced drug metabolism and clearance with ageing, potential drug–drug interactions, adverse drug events and comorbidities. Many painkillers, such as NSAIDS, are considered high risk in the older patient, reducing the number of potential analgesics.

Pain assessment

Identifying pain may be challenging in the older patient due to the points in Box 3.1. Alternative expressions such as ‘is it sore?’, ‘does it hurt?’ and ‘are you uncomfortable?’ may be useful. In the patient with dementia or communication difficulties, agitation or a change in behaviour (Table 3.1) may indicate poorly controlled pain, and carers or family members may detect this better than clinicians unfamiliar with the patient.

Table 3.1 Atypical observations in older patients with pain (3)

| Type | Description |

| Autonomic features | Pallor, sweating, tachypnoea, tachycardia, altered breathing, hypertension |

| Facial expressions | Grimacing, wincing, frowning, brow raising, brow lowering, nose wrinkling, lip puckering |

| Body movements | Hand wringing, repetitive movements, rocking, increased tone, guarding, bracing |

| Vocalisation | Sighing, grunting, groaning, moaning, screaming, calling out, aggressive/offensive speech |

| Interpersonal interactions | Aggression, withdrawal, resisting, refusal of care |

| Mental status changes | Confusion, crying, distress, irritability, agitation |

The location and cause of the pain may be obvious or further history, examination and investigation may be required. A pain map or diagram which the patient can annotate may be useful. A patient may have more than one type of pain simultaneously. Pain has physical, psychological, spiritual and social contributions, as well as a variable impact on functional ability, and to provide adequate treatment, all these factors should be assessed.

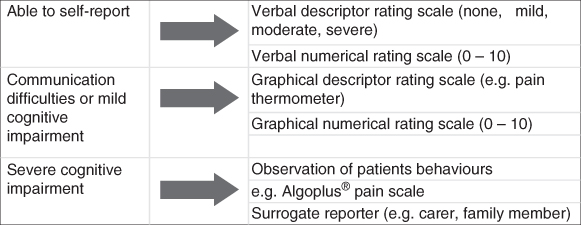

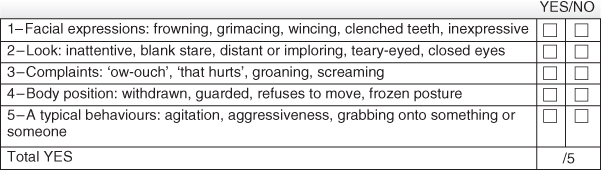

Patients who are fully alert and orientated will be able to report pain severity according to a verbal rating scale (Figure 3.1). Observational pain tools, of which there are a number available, may be required for patients with cognitive impairment. A simple validated tool for the older patient, which takes less than 1 minute to perform and incorporates some of the features in Table 3.1, is the Algoplus® pain scale (Figure 3.2).

Figure 3.1 Methods of assessing pain intensity in the older population (3).

Figure 3.2 Algoplus® pain scale: acute pain-behaviour scale for older persons with inability to communicate verbally.

Source: From Rat P, Jouve E, Pickering G, et al. Validation of an acute pain-behavior scale for older persons with inability to communicate verbally. Eur J Pain 2011;15(2):198.e191–10; with permission from Wiley & Sons.

Management of acute pain

Treat the underlying cause

Acute onset of pain may represent a life-threatening emergency, such as ST elevation MI, or bowel perforation, and resuscitation and other management should take place simultaneously. Sometimes providing definitive treatment, e.g. reducing a fracture, may reduce the need for further analgesia.

Non-pharmacological pain management strategies

Reassurance and an explanation of symptoms should be provided. In traumatic injuries, positioning, elevation, splinting, a cold compress or wound dressings may be effective.

Regional anaesthesia such as fascia iliaca block or femoral nerve block in hip fractures can be very effective and is opioid-sparing (Chapter 12).

Pharmacological pain management

Analgesia should be given promptly after identifying pain. Older patients may have concerns about the over-use of analgesia for fear of developing tolerance, dependence or addiction (4), and this should be addressed if necessary.

Mild to moderate pain

Paracetamol (acetaminophen) is the safest non-opioid analgesic in the older patient.

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatories (NSAIDs) should generally be avoided as they may precipitate renal failure, cardiac failure or gastrointestinal bleeding. With extreme caution in an otherwise well older adult, a short course of a moderate strength NSAID such as ibuprofen may be useful. Beware of potential drug interactions, e.g. with aspirin, warfarin or ACE (angiotensin converting enzyme) inhibitors, and consider prescribing a proton pump inhibitor to prevent gastric complications.

Moderate acute pain

Moderate to acute pain is likely to require the addition of opioid analgesia. Starting doses should be 25–50% lower than with younger adults, especially in the presence of renal failure. Side effects such as constipation, nausea and vomiting, delirium, drowsiness and increased falls risk are more common in the older patient. There is no ideal opioid; all have slightly different side effect frequencies and clinician preference varies. Many hospitals have formularies which may limit the choice of drugs available.

Consider a mild opioid such as codeine or hydrocodone, or prescribe regular small doses of oxycodone or morphine. Morphine and codeine have metabolites that accumulate in impaired renal function. Oxycodone has a shorter half-life and little to no toxic metabolites. Regular opioids should be co-prescribed with a stool softener and/or stimulant laxative (5).

Severe acute pain

This will usually require parenteral opioids. ‘Start low and go slow’ is a useful maxim (4). A small initial bolus should be given, e.g. 1–2 mg of morphine. Peak effects may be delayed: allow time to assess effectiveness before repeat dosing. It may take several doses over the course of 1 hour to achieve pain control. Careful monitoring for hypotension or respiratory depression is required in the older patient.

Reassessment of pain severity should occur after any intervention; this is as important as assessing pain initially.

Chronic pain management

The management of chronic pain is discussed below under ‘Palliative Care’.

Palliative care in the acute setting

Advanced terminal illness is a relatively common presentation to the ED, and all physicians should be aware of the key management interventions necessary to provide comfort care at the end of life. This section discusses patients presenting with a terminal illness who are not necessarily at the end of life, and those who are actively dying.

Introduction

The focus of medicine is traditionally on preserving life and preventing death. Palliative care may be somewhat counterintuitive in the emergency environment; however, for the patient with advanced disease, such as malignancy or dementia, interventions to prolong life may not be appropriate or wanted by the patient.

Presentation to hospital may represent a palliative care emergency, rapid or unexpected deterioration, unrelated medical or surgical problem, poorly controlled symptoms or inconsistent community palliative care services. Patients may present with a requirement for end-of-life care, with family being unable to cope in their usual place of residence.

Definition

Palliative care aims to improve the quality of life of patients and their families facing life-threatening illness, through the prevention and integrated treatment of pain, and other symptoms, whether physical, psychosocial or spiritual (6). It also incorporates care given during the last few hours or days of a patient’s illness, termed ‘end-of-life care’.

Background

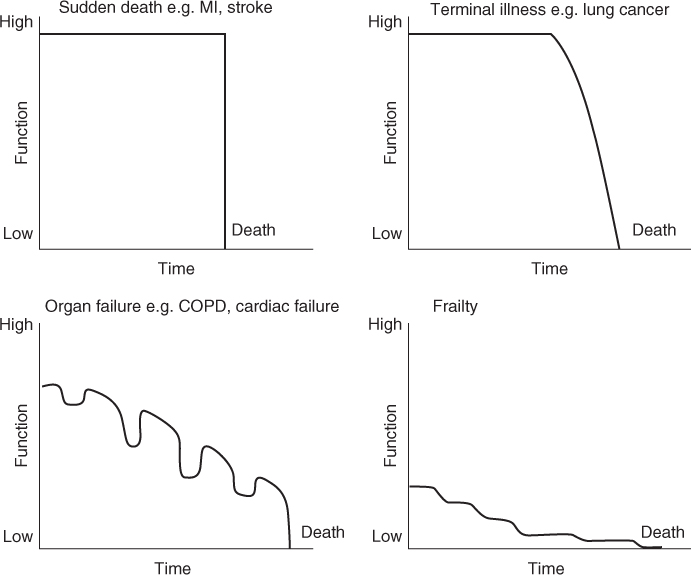

Diagnosis of terminal illness is often easier in cases of advanced malignancy, where decline frequently occurs in a linear manner, affording some degree of predictability. However, other life-limiting diagnoses, such as dementia, cardiac or respiratory failure also have substantial palliative care needs (7). In these cases, deterioration may occur more slowly and gradually, interspersed with exacerbations of illness followed by recovery (Figure 3.3).

Figure 3.3 Trajectories of dying.

Source: Reproduced from Lunney JR, Lynn J, Hogan C. Profiles of Older Medicare Decedents. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002 Jun;50(6):1108–12 with permission from Wiley & Sons.

Identifying patients requiring palliative care

Palliative care services can assist in identifying patients who, whilst not imminently dying, require improved control of difficult symptoms such as pain, dyspnoea or nausea; help avoid burdensome or futile treatments; and facilitate further support in the community or hospice care. 70–75% of people older than 65 years known to have a life-limiting condition visit an ED within the last few months of their life (8, 9). Box 3.2 highlights factors that may assist in identifying patients in the ED who would benefit from palliative care services.

General approach to the patient with palliative care needs

As mentioned above, patients with advanced illness may present with a range of problems related to or unrelated to their principle diagnosis. Box 3.3 outlines the approach to initial assessment.

| Causes | Symptoms and signs | Management | |

| Bowel obstruction | Compression or intraluminal obstruction by tumour | Abdominal pain, vomiting, constipation | Conservative, e.g. NG decompression, anti-spasmodic medication, antisecretory agents (e.g. octreotide) or surgical management (Chapter 15) |

| Hypercalcaemia | Bone invasion or secretion of PTHrP* | Thirst, nausea, delirium, constipation, renal stones | IV fluid resuscitation, bisphosphonates (Chapter 17) |

| Spinal cord compression or cauda equina syndrome | Vertebral metastasis or oedema following radiation | Worsening back pain, loss of pain and temperature sensation, leg weakness and reduced mobility, bowel or bladder sphincter disturbance | Steroids, urgent neurosurgical or radiotherapy referral (Chapter 12) |

| Dyspnoea or respiratory failure | Pleural effusion, fluid overload, pulmonary embolus, pneumonia, anaemia | Reduced exercise tolerance, wheeze, cough, orthopnoea | Small doses of opioids or benzodiazepines. Drainage of pleural effusions may be useful. Consider diuretics if appropriate. Oxygen may help (Chapter 6) |

| Superior vena cava obstruction | Tumour invasion or compression Intraluminal thrombosis | Periorbital oedema, facial swelling, dyspnoea, cough, engorged neck veins, headache | Steroids ± diuretics Intravascular stenting, thrombolysis or radiotherapy |

| Delirium | Medications such as opioids and steroids, sepsis, raised ICP or brain metastases | Fluctuating mental state. Altered concentration, attention and disordered thinking | Exclude easily treated causes such as hypoglycaemia and hypercalcaemia. Small doses of antipsychotics may be required (Chapter 18) |

| Severe haemorrhage | Tumour invasion of a major blood vessel | Haemoptysis, haematemesis, rectal or vaginal bleeding | May require urgent intervention or palliation with subcutaneous midazolam if thought to be an end-of-life event |

NG, nasogastric; ICP, intracranial pressure.

* PTHrP, parathyroid hormone related peptide.

Palliative care emergencies

A palliative care emergency is an unexpected change in a patient’s condition in the context of an underlying life-limiting illness. When embarking on investigation and treatment, consider the likely outcome and reversibility, current functional status, life expectancy, risks and benefits of treatment and the wishes of the patient and their family.

Emergencies in palliative care usually result from advancing malignancy and include the conditions featured in Table 3.2.

Addressing symptom management

Pain is the commonest symptom in palliative care, experienced in 70% of patients with both malignant and non-malignant terminal illnesses. As mentioned above, pain management includes consideration of physical, psychological, spiritual and social factors. The choice of regime for analgesia depends on multiple factors including setting, available routes and the presence of any renal impairment. Regular reassessment of pain is required.

Regular analgesia should be prescribed along with ‘breakthrough’ doses if needed. Ensure laxatives are also administered if opioid analgesia is used. Once stable pain control is achieved, an equivalent dose of modified-release opioid may be given. Certain types of pain may require adjuvant analgesics such as antidepressants, anticonvulsants and corticosteroids. Bone pain may respond to bisphosphonates or radiotherapy. Local topical treatment with gels or patches may be valuable. Neuropathic pain may improve with pregabalin, gabapentin or (with appropriate supervision), non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

Nausea and vomiting are common in terminal illness, often significantly impacting on quality of life. Causes may be the underlying disease process or secondary to opioid analgesia, chemotherapy agents, brain metastases, constipation or bowel obstruction. Consider both pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatments: good mouth care may make a significant difference. Choice of antiemetic will depend on the underlying cause; consult local palliative care guidelines.

Other symptoms such as constipation, low mood, anxiety and sleep problems should be assessed and treated by the palliative care team.

Communication with patient, carers and family

Patients have concerns and unanswered questions on presentation to the ED. Identifying and addressing these is a crucial. Although the busy and crowded environment of the ED often makes discussion difficult, a few simple questions as suggested in Box 3.4 may help clarify the patient’s wishes and help form the management plan.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree