Soft tissue sarcomas are a heterogeneous group. Because of their rarity, they frequently pose diagnostic problems for surgical pathologists. Accurate diagnosis of these tumors is enhanced by knowledge of the clinical features of the given lesions and, at times, by application of immunohistochemical and molecular techniques. In this chapter, the lesions are described essentially in accordance with the World Health Organization (WHO) classification.1 It is beyond the scope of this chapter to cover all described soft tissue entities; both expanded2 and concise3 textbooks are also available.

Grading soft tissue tumors applies only to sarcomas. Histologic grade is an important (if not the most important) prognostic parameter in soft tissue neoplasia.4 Therefore, general grading schemes have been devised and studied over the past several decades in that correlate with prognosis, recurrence, metastasis free, and overall survival4,5 but the French Federation of Cancer Centers system, that uses differentiation, mitosis, and necrosis in their grading system provides the best prognostic information6,7 (Table 25-1) and is the preferred one for the AJCC staging systems as of 2010.8

French Federation of Cancer Centers (FNCLCC, Fédération Nationale des Centres de Lutte Contre le Cancer) Grading Systema

| Histologic Parameters | ||||

Scores are added to assign grade Grade 1: Score 2–3 2: Score 4–5 3: Score 6–8 | ||||

| Scoring Parameters | ||||

| Score | Differentiation | Mitosis | Necrosis | |

| 0 | Not used | Not used | No necrosis | |

| 1 | Resembling normal tissue | 0–9/field | <50% necrosis | |

| 2 | Sarcomas for which histologic typing certain | 10–19/field | >50% necrosis | |

| 3 | Embryonal and undifferentiated sarcomas | >20/field | ||

Staging of any cancer is a portrait of its extent of disease at the time of initial diagnosis. Unique to sarcomas, grade itself is incorporated into the staging schemes. A key feature of the AJCC staging system is that 5 cm appears to be a prognostic “cutoff” size. It should also be noted, that in contrast to carcinomas, lymphoid metastasis is not a typical feature of sarcomas with the following exceptions: synovial sarcoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, epithelioid sarcoma, and clear cell sarcoma.

Soft tissue tumors are classified according to the adult tissue types that the lesional cells resemble. The classification does not necessarily imply that the tumor arose from such cells. A list of most sarcoma types appears in Table 25-2 but a detailed discussion of all of them is beyond the scope of this text. Classification can frequently be confirmed exploiting molecular techniques. Table 25-3 presents many known genetic alterations in soft tissue tumors. Table 25-4 shows some immunohistochemical stains and their frequent uses. A discussion of selected subtypes follows.

Types of Sarcomas and “Borderline” Soft Tissue Tumors

| Differentiation Type | Sarcomas |

|---|---|

| Adipocytic |

|

| Fibroblastic |

|

| Fibrohistiocytic |

|

| Skeletal muscle |

|

| Vascular |

|

| Gastrointestinal stromal tumor | |

| Nerve sheath tumors |

|

| Tumors of uncertain differentiation |

|

| Undifferentiated sarcomas |

|

Translocations, Molecular Alterations in Soft Tissue Tumorsa

| Specific Chromosomal Translocations and Other Alterations Established Cytogenetically and the Corresponding Gene Changes in Some Mesenchymal Tumors | ||

|---|---|---|

| Tumor | Translocation or Other Alteration | Gene Changes |

| Alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma | t(2;13)(q35;q14) | PAX3-FOXO1 |

| t(1;13)(p36;q14) | PAX7-FOXO1 | |

| Alveolar soft part sarcoma | t(X;17)(p11.2;q25) | ASPL-TFE3 |

| Angiomatoid fibrous histiocytoma | t(12;22)(q13;q12) | EWSR1-ATF1 |

| t(12;16)(q13;p12) | FUS-ATF1 | |

| t(2;22)(q33;q12) | EWSR1-CREB1 | |

| Atypical lipomatous tumor/well-differentiated liposarcoma | Supernumerary or ring marker chromosomes | Amplification of MDM2, CDK4, HMGA2 genes |

| Clear cell sarcoma (malignant melanoma of soft parts; soft tissue) | t(12;22)(q13;q12) | ATF1-EWS |

| Clear cell sarcoma of gastrointestinal tract | t(2;22)(q33;q12) | EWSR1-CREB1 |

| Congenital fibrosarcoma and mesoblastic nephroma | t(12;15)(p13;q25) | ETV6-NTRK3 |

| Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (giant cell fibroblastoma) | t(17;22)(q22;q13) | COL1A1-PDGFB |

| Desmoplastic small round cell tumor | t(11;22)(p13;q12) | EWSR1-WT1 |

| Epithelioid hemangioendothelioma | t(1;3)(p36;3q25) | WWTR1-CAMTA1 |

| Epithelioid sarcoma | Alterations 22q11.2 | Inactivation of hSNF5/INI1 |

| Endometrial stromal sarcoma | t(7;17)(p15;q21) | JAZF1-JJAZ1 |

| Ewing sarcoma and peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumors | t(11;22)(q24;q12) | EWSR1-FLI1 |

| t(21;22)(q22;q12) | EWSR1-ERG | |

| t(7;22)(p22;q12) | EWSR1-ETV1 | |

| t(17;22)(q12;q12) | EWSR1-E1AF | |

| t(2;22)(q33;q12) | EWSR1-FEV | |

| Extrarenal malignant rhabdoid tumor | Alterations 22q11.2 | Inactivation of hSNF5/INI1 |

| Fibromatosis | Trisomy 8 or 20; loss of 5q | Somatic CTNNB1 or APC mutations (only in deep tumors) |

| Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor | 2p3 rearrangements | ALK-various partners |

| Low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma | t(7;16)(q33;p11) | TLS(FUS)-CREB3L2 |

| Myoepithelioma | Translocations involving 22q12 | EWSR1-POU5F1 and others |

| Myxoid chondrosarcoma, extraskeletal | t(9;22)(q22;q12) | EWSR1-NR4A3 |

| t(9;17)(q22;q11) | TAF1168-NR4A3 | |

| t(9;15)(q22;q21) | TCF12-NR4A3 | |

| Myxoid/round cell liposarcoma | t(12;16)(q13;p11) | TLS(FUS)-CHOP (DDIT3) |

| t(12;22)(q13;q12) | EWSR1-CHOP (DDIT3) | |

| Myxoinflammatory fibroblastic sarcoma | t(1;10)(p22;q24); Controversial | TGFBR3-MGEA5 |

| Ossifying fibromyxoid tumor | See right | PHF1 rearrangements |

| Synovial sarcoma | t(X;18)(p11;q11) | SSX18-SSX1, SSX18-SSX2, SSX18-SSX4 fusions |

Some Immunohistochemical Stains Used to Evaluate Soft Tissue Tumors

| Antibody/Immunohistochemical Preparation | Useful for Recognizing |

|---|---|

| Keratins | Synovial sarcoma, epithelioid sarcoma, malignant rhabdoid tumor, myoepithelioma, sarcomatoid carcinomas, epithelioid sarcoma-like hemangioendothelioma/pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma |

| S100 protein | Melanoma, nerve sheath tumors, myoepithelioma, clear cell sarcoma, chondrosarcomas |

| MUC4 | Low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma, sclerosing epithelioid fibrosarcoma |

| Beta catenin | Fibromatosis |

| ALK | Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor |

| Smooth muscle actin | Smooth muscle tumors, any lesion with myofibroblastic differentiation, myoepithelioma |

| Desmin | Smooth and skeletal muscle tumors, myoepithelioma |

| Calponin | Smooth muscle tumors, any lesion with myofibroblastic differentiation, myoepithelioma |

| Caldesmon | Smooth muscle tumors, myoepithelioma |

| MDM2, CDK4 | Well-differentiated and dedifferentiated liposarcoma |

| TFE3 | Alveolar soft part sarcoma |

| Myogenin, MyoD1 | Skeletal muscle tumors |

| INI1 | Malignant rhabdoid tumor, epithelioid sarcoma (loss of nuclear staining) |

| CD99 | Ewing’s sarcoma, synovial sarcoma, solitary fibrous tumor |

| BCL2 | Synovial sarcoma, solitary fibrous tumor, various lymphomas, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans |

| CD34 | Solitary fibrous tumor, vascular tumors, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, many benign lesions, various hematopoietic lesions |

| TLE1 | Synovial sarcoma (suffers from poor specificity) |

| CD117 | Gastrointestinal stromal tumor, many other tumors, including melanoma |

| DOG1 | Gastrointestinal stroma tumor, can label gastric carcinomas as well |

| EMA | Synovial sarcoma, many epithelial lesions |

| HMB45, MART1 | Melanoma, clear cell sarcoma |

| CD31 | Vascular lesions, various hematopoietic lesions, histiocytes |

| ERG | Vascular lesions, prostate carcinoma |

Once regarded as the most common type of sarcoma,9 adult fibrosarcoma is now rarely diagnosed. It is essentially a diagnosis of exclusion because many lesions classified as fibrosarcomas in the past are readily recognized as malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors, synovial sarcomas, or pseudosarcomas using current criteria and modern ancillary studies. However, adult fibrosarcoma is defined, as it was at the time of its initial description, as a malignant tumor composed of fibroblasts.10 It must be distinguished from congenital-infantile fibrosarcoma and from other specific subtypes of fibroblastic sarcomas. It probably accounts for 1% to 5% of adult sarcomas.11 Classical fibrosarcoma is most common in middle-aged and older adults with no gender predilection. Fibrosarcoma usually involves deep soft tissues of the extremities, trunk, head, and neck. Hypoglycemia has been reported and has been related to elaboration of insulin-like growth factor by the tumor cells, a phenomenon also observed in association with solitary fibrous tumors of the pleura.12,13 Fibrosarcoma can arise in dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans and fibrosarcoma-like lesions can complicate solitary fibrous tumors.

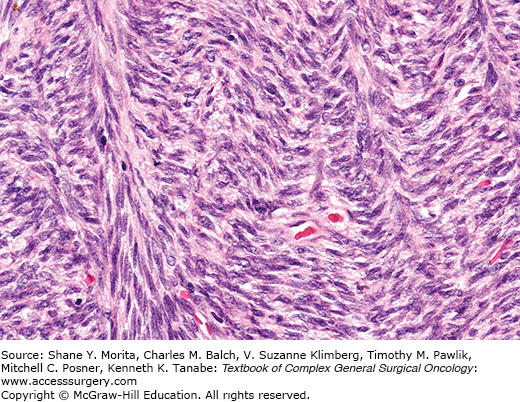

This neoplasm is composed of spindle-shaped cells, characteristically arranged in sweeping fascicles that are angled in a chevron-like or herringbone pattern (Fig. 25-1). Storiform areas can be seen. The cells have tapered darkly staining nuclei with variably prominent nucleoli and scant cytoplasm. Mitotic activity is almost always present but variable. Higher-grade tumors have more densely staining nuclei, and can display focal round cell change and multinucleated cells, but sarcomas with significant pleomorphism are currently classified as malignant fibrous histiocytomas. The stroma has variable collagen, from a delicate intercellular network to paucicellular areas with diffuse or “keloid-like” sclerosis or hyalinization. Myxoid change and osteochondroid metaplasia can occur. Fibrosarcomas are positive for vimentin and very focally for smooth muscle actin representing myofibroblastic differentiation. Some cases arising in dermatofibrosarcoma are CD34 positive.

There are no recent series of fibrosarcomas classified using modern techniques. In the older literature, behavior relates to grade and to general factors of tumor size and depth from the skin. The probability of local recurrence relates to completeness of excision.14–16 Fibrosarcomas metastasize to lungs and bone, especially the axial skeleton, and rarely to lymph nodes in about 10% to 65% of patients. Five-year survival is on the order of 50%.

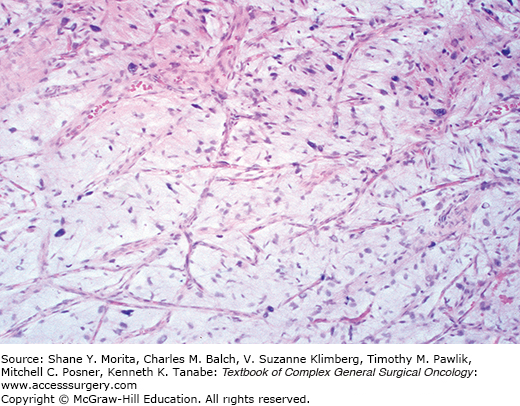

Low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma is a tumor composed of bland, fibroblast-like cells with a swirling, whorled, vaguely storiform pattern in a fibrous and focally myxoid stroma, occasionally with plexiform vasculature. These first reports highlighted their deceptive resemblance to fibromatoses17 (Fig. 25-2). These tumors have little mitotic activity and minimal nuclear pleomorphism (since it is a translocation-associated sarcoma it has uniform cells18,19). This lesion recurs, but many cases also metastasize.

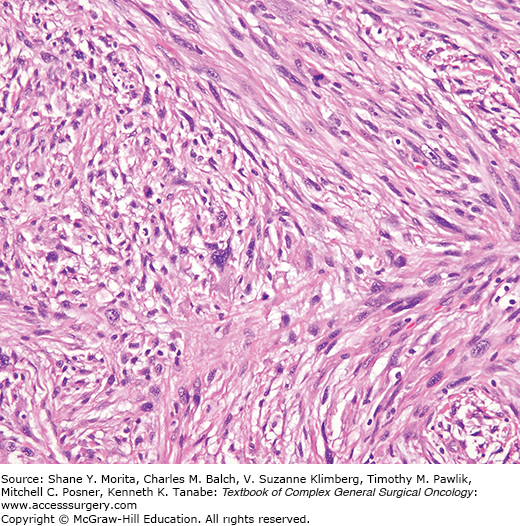

Hyalinizing spindle cell tumor with giant rosettes20 is an entity within a spectrum with low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma.21 These tumors have infiltrative borders microscopically and are composed of bland spindled cells situated in a hyalinized to myxoid stroma, often with “cracking” artefact in the collagen. Characteristic features consist of scattered large rosette-like structures that often merge with serpiginous areas of dense hyalinization (Fig. 25-3). The rosettes consist of a central collagen core surrounded by a rim of rounded cells morphologically and immunophenotypically different from the cells of the spindled stroma.

An identical characteristic translocation is found in both low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma and hyalinizing spindle cell tumor with rosettes; t(7;16)(q33;p11)22 fuses the FUS gene (also called TLS) to CREB3L2 (also called BBF2H7).23 As mentioned above, MUC4 labeling has been reported as a characteristic feature of low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma.24

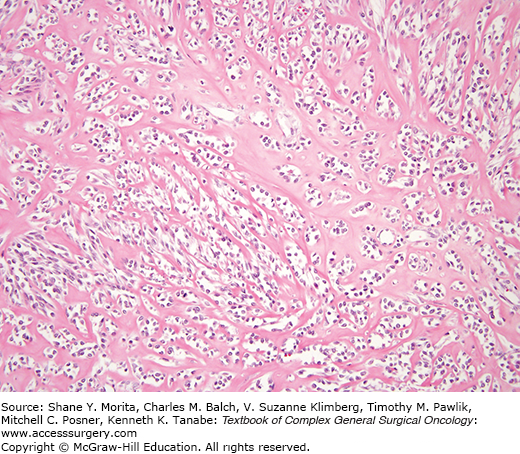

Sclerosing epithelioid fibrosarcoma25 can mimic metastatic carcinoma, particularly lobular carcinoma of the breast. These lesions affect primarily the deep musculature of adults without gender predilection, usually involving the lower limbs and limb girdles. Most are large. These lesions display a white gray cut surface characterized microscopically by a uniform population of small slightly angulated rounded cells with scant cytoplasm arranged in nests, cords, and sometimes in an “Indian file” array (Fig. 25-4). There is a background of dense sclerosis, minimal inflammation, and sometimes zones of cartilage and mineralization. Mitotic activity is scant. These tumors can behave quite aggressively. In the earlier series, 53% of patients had persistent disease or local recurrence and 43% had metastases. Eighty-six percent of patients in the more recent series had metastases and over half of the reported patients had died of disease during the follow-up period.

Although the story is incompletely developed, sclerosing epithelioid fibrosarcoma can be tentatively considered as a high-grade form of low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma as the two tumors share genetic alterations and sclerosing-epithelioid-like zones can be encountered in low-grade fibromyxoid sarcomas.26–30 The features are not specific on cytology.

“Acral myxoinflammatory fibroblastic sarcoma”31 and “inflammatory myxohyaline tumor (IMHT)”32 are terms used to described the same entity.

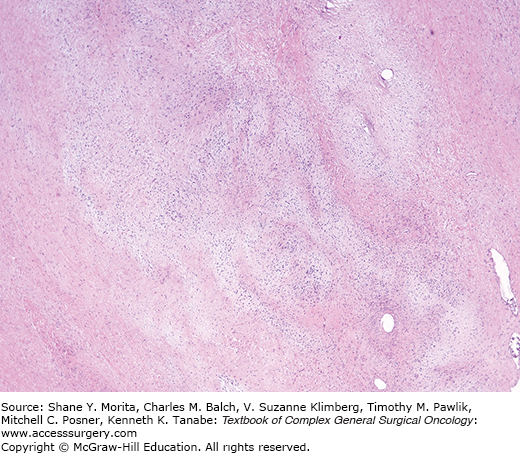

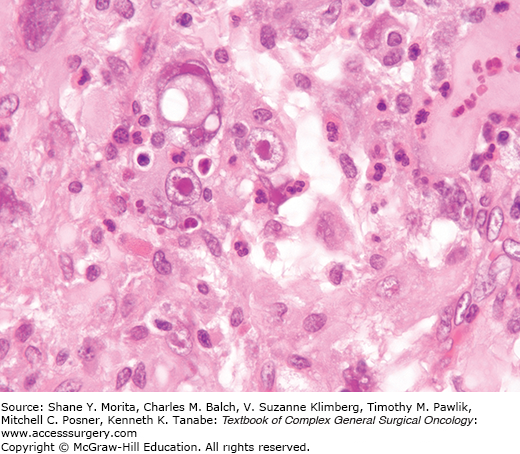

These tumors, presenting as painless masses arise over a wide age range and typically affect the hands and feet, although more axial sites can be affected such that the WHO dropped the term “acral” from the 2002 classification.33 These tumors are infiltrative and multinodular (Fig. 25-5), characterized histologically by dense inflammation merging with stroma varying from myxoid to hyalinized and containing sheets of epithelioid spindled cells. Some lesions contain foamy histiocytes, giant cells, and hemosiderin. Amid the inflammatory backdrop, scattered bizarre cells having large vesicular nuclei and macronucleoli reminiscent of Reed–Sternberg cells or virocytes are present. Neither CMV nor EBV are detected. Despite the cytologic atypia, mitotic activity is minimal.

On molecular testing, these lesions show t(1;10) with rearrangements of TGFBR3 and MGEA5, a feature they share with hemosiderotic fibrohistiocytic lipomatous lesion.34 These tumors may also be in the same family as pleomorphic hyalinizing angiectatic tumor (PHAT),35 an evolving story at this writing.

Recurrences are common but metastases are rare.

Myxoid MFH as described by Weiss and Enzinger36 comprised 20% of all MFH, and was defined as having over 50% of myxoid change, with characteristic nodularity, vascular pattern, atypical spindle cells, and a tendency to superficial location (Fig. 25-6). The myxoid nodules merged into areas of pleomorphic MFH. The likelihood of metastasis related to depth from the skin and was inversely proportional to the amount of myxoid change.

Myxofibrosarcoma was described at the same time37 as a subcutaneous or deep multinodular tumor of older adults composed of thin tapered spindle cells in a myxoid pattern, with a prominent vascular pattern. The tumor cells are sometimes vacuolated, resembling lipoblasts, but are irregularly shaped, and contain alcianophilic secretion.

These tumors tend to affect the proximal extremities of older adults and are most commonly superficial. They tend to be mistaken for myxoid liposarcoma but they are easy to separate from myxoid liposarcoma; the latter is a translocation-associated sarcoma so thus has uniform rather than pleomorphic nuclei18 and, furthermore it tends to be deep and in younger individuals.

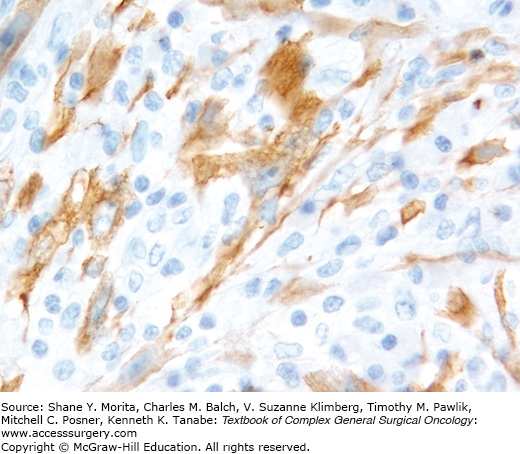

Although these lesions were originally described as separate entities, they are now recognized as ends of a spectrum of tumors unified by a common molecular profile. They are grouped together by the WHO.33 Gene fusions involving anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) at chromosome 2p23 have been described in these lesions.38 By immunohistochemistry, ALK protein has been detected in about 60% of cases (Figs. 25-7 and 25-8), a finding that can sometimes be exploited for diagnosis39,40 as well as targeted therapy. The cytologic findings of these tumors have not been well described.

FIGURE 25-8:

Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor. This is an ALK stain from the tumor shown in Fig. 25-7.

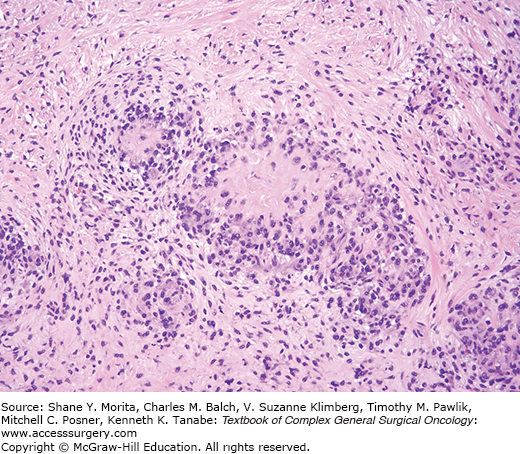

The same lesions, described using the term “inflammatory fibrosarcoma,” were reported first and were most common in childhood with a mean age of 8 years (range 2 months to 74 years). As described in the AFIP series,41 this tumor arises within the abdomen, involving mesentery, omentum, and retroperitoneum (over 80% of cases), with occasional cases in the mediastinum, abdominal wall, and liver. Sometimes there are associated systemic symptoms. The tumor can be solitary or multinodular (30%) and up to 20 cm in diameter. The tumors are composed of myofibroblasts and fibroblasts in fascicles or whorls, and also histiocytoid cells. The tumors invade adjacent viscera; 37% recurred and three cases (11%) metastasized. A quarter of the patients died of disease.

Lesions described as “inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors (IMT),” also known as inflammatory pseudotumor, were first well described in the lungs and later became recognized in extrapulmonary locations.42

Cytogenetic and molecular evidence in both inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor and inflammatory fibrosarcoma supports a clonal origin. It is found in soft tissue, in omentum and retroperitoneum, and involving viscera. IMT has been reported in patients between 3 months and 46 years, but mostly in childhood (mean age 9 years) with a slight male predominance, and some cases are associated with systemic symptoms. A small number recur, especially when multinodular. They form firm white infiltrative masses, and histologically there are three patterns: (1) fasciitis-like, with vascular, myxoid, and inflamed stroma, including plasma cells43; (2) fascicular MFH or leiomyosarcoma like spindle cell areas with inflammation; and (3) sclerosed desmoid-like areas with calcification.

Regardless of terminology, these tumors express actin, often express cytokeratins, and often express ALK protein or display ALK rearrangements. An epithelioid form has been observed44 and many cases show a backdrop of IgG4-reactive plasma cells,45 a finding that is probably nonspecific.

Malignant fibrous histiocytoma was initially classified into storiform-pleomorphic, myxoid, giant cell, xanthomatous, and angiomatoid types. The angiomatoid type is now regarded as a “borderline” lesion, renamed “angiomatoid fibrous histiocytoma” (covered in the chapter on skin). The myxoid subtype is, for practical purposes, subsumed under “myxofibrosarcoma” and discussed above. This category assumes many tumors that were historically classified as fibrosarcoma, pleomorphic rhabdomyosarcoma, or undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma. It was the most common sarcoma diagnosis rendered in the 1980s and early 1990s, but application of newer techniques has reduced the number of cases so diagnosed in more recent years, also eliminating many misdiagnosed cases of pleomorphic sarcomatoid carcinomas, melanomas, and lymphomas. It has been suggested that MFH is not an entity but a collection of poorly differentiated neoplasms better classified with comprehensive examination.46 Certainly, there may be neoplasms “lumped” in this classification that could be better characterized, but the term MFH remains a reasonable descriptive one and this is a phenotype that can be recognized reproducibly although the terminology “undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma” has somewhat supplanted the “malignant fibrous histiocytoma” terminology. Masqueraders are now readily unmasked with modern techniques.

This is a tumor of older adults and usually affects the limbs and limb girdles followed by the retroperitoneum, trunk, or head and neck. Pediatric cases are uncommon but behave similarly. Occasional examples have been associated with hyperlipidemia47 and even as a component of hereditary nonpolyposis colon cancer syndrome with mismatch repair defects.48 These neoplasms typically attain a large size with zones of hemorrhage and necrosis. Deep tumors are usually circumscribed whereas superficial ones can sometimes track along connective tissue septa and often require a wider excision than palpation would suggest.49 There are many published studies of these tumors and behavior is similar in all of them; overall survival is usually on the order of 50% to 60% and the key prognosticators are tumor grade and tumor size.

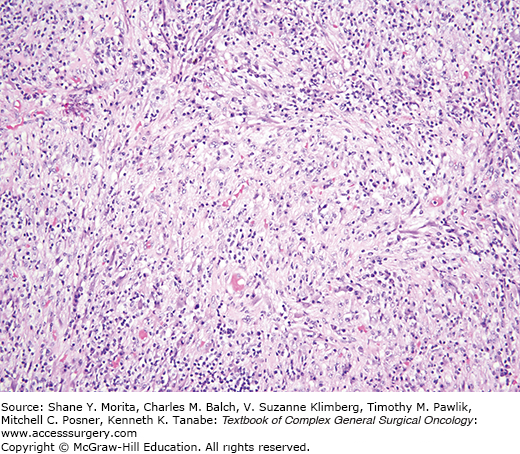

Histologically there is at least focally a storiform pattern (Fig. 25-9) and the tumor consists of a variable proportion of atypical pleomorphic spindle cells and polygonal cells. There are frequently abundant pleomorphic multinucleated cells with ample eosinophilic cytoplasm. The stroma has variable amounts of collagen. Tumor cells have ultrastructural features of fibroblasts, myofibroblasts, and cells lacking differentiation.11,50 There is no specific immunohistochemical profile for these tumors. The tumor should lack specific differentiation but various intermediate filaments may be expressed. Most tumors react with vimentin but desmin or keratin may be expressed. Tumors having desmin or keratin might be interpreted as carcinomas, pleomorphic rhabdomyosarcomas, or pleomorphic leiomyosarcomas, but such tumors can lack ultrastructural features of specific differentiation.51,52 Expression of smooth muscle type markers (actins, desmin, calponin) may be best attributable to myofibroblastic differentiation in these tumors (“pleomorphic myofibrosarcoma”).50,53 Cytogenetic/molecular studies yield complex karyotypes and there is no specific genetic alteration.

These neoplasms are discussed above under “myxofibrosarcoma.”

Lesions described as “giant cell MFH” account for about 10% of all MFH and feature numerous osteoclast-like giant cells in addition to the atypical spindle and polygonal cells. It is typically multinodular and may be surrounded by peripheral bone formation.54 This latter component may be metaplastic or neoplastic. Distinguishing such cases from extraskeletal osteosarcoma is difficult and such tumors would probably be currently reported as “pleomorphic undifferentiated sarcomas.”

This variety has been said to account for fewer than 5% of MFH, to be located in the retroperitoneum, and to be aggressive.55,56 It is composed of sheets of large histiocyte-like cells, many of which have a bland appearance also but with scattered pleomorphic tumor cells. There is often an intense background neutrophilic infiltrate and minimal collagen. Since they are rare, they are not well studied but most are probably, instead, dedifferentiated liposarcomas57; see below.

In fact, the WHO opted in 2013 to use the term “atypical lipomatous tumor” and drop the term “well-differentiated liposarcoma” since such tumors never metastasize unless they dedifferentiate.1 However, both terms are acceptable. Atypical lipomatous tumor/well-differentiated liposarcoma is the commonest subtype of adipose tissue lesion with malignant potential. These tumors nearly always occur in adults with no gender predilection.58–60 They most commonly arise in the deep soft tissues of the proximal extremities and the retroperitoneum. Occasionally retroperitoneal examples may present as groin masses by virtue of local extension into the peritoneal-lined scrotal sac.61 Historically, when these tumors arose within tissues readily accessible to the surgeon, they have been classified as “atypical lipomas” or “atypical lipomatous tumors.”59,60,62,63 Although these tumors are histologically and cytogenetically identical to their deeply located counterparts, the natural history of the superficial tumors is sufficiently different that they may be considered as a separate group. However, they are not immune to undergoing dedifferentiation to a high-grade sarcoma.64 Most patients with these neoplasms present with painless slow growing soft tissue masses. Intra-abdominal tumors typically are larger than the extremity tumors and patients with abdominal tumors may present with altered abdominal girth or altered gastrointestinal tract function. Primary groin tumors commonly simulate inguinal or femoral herniae.65

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree