Melissa K. Andrew

Social Vulnerability in Old Age

People’s lives are embedded in rich social contexts; many social factors affect each of our lives every day. This is perhaps more noticeable for older adults because declines in health and functional status may increase reliance on social supports and diminish opportunities for social engagement, even in the face of social circles dwindling due to declining health and function among peers.

This chapter will provide an overview of how social factors affect health in old age, through a discussion of the concept of social vulnerability. Association with health outcomes relevant to geriatric medicine, including function, mobility, cognition, mental health, self-assessed health, frailty, institutionalization, and death, will be the focus, with particular emphasis on the relationship between social vulnerability and frailty. Detailed discussion of social gerontology and of standardized instruments and measurement scales used in the social assessment of older people is beyond the scope of this chapter; interested readers are referred to Chapters 29 and 36 on these topics.1,2

Background and Definitions

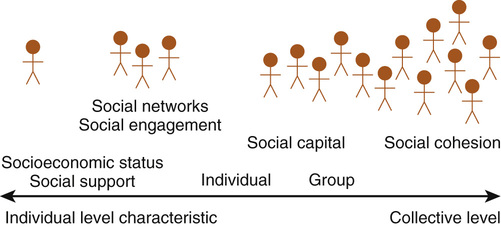

Many social factors influence health, including socioeconomic status, social support, social networks, social engagement, social capital, and social cohesion.3–10 As such, the social context is key to a broad understanding of health and illness. Perhaps due in part to the numerous disciplines in which this line of inquiry has been investigated, including epidemiology, sociology, geography, political science, and international development, terminology and methods of approach have differed. In some cases, the same terminology has been used to refer to different ideas, whereas in others, divergent terminology obscures underlying commonalities. There has also been debate surrounding the level, from individual to communal, at which some elements of the social context are relevant and, as such, how they can be measured.3,11,12 In the following section, various terms and concepts will be defined and discussed, and each will be placed in context on the continuum from individual to group influence (Fig. 30-1).

Socioeconomic Status

Socioeconomic status (SES) is a broad concept that includes factors such as educational attainment, occupation, income, wealth, and deprivation. There are three broad theories of how socioeconomic status might relate to health.13 The materialist theory states that gradients in income and wealth are associated with varying levels of deprivation, which in turn affects health status because those with fewer means have inferior access to health care and the necessities of life. Another view is that education influences health through lifestyle and health-related behaviors such as diet, substance use, and smoking. A third theory sees social status (often measured by occupation) and personal autonomy as key influences on health, particularly through the stresses that accompany low social status and low autonomy.13 Measurement of each of these elements of SES may present difficulties in the older adult population. Older adults are likely to be retired, and some older women may never have worked outside the home, making occupational assessments problematic. Income is associated with employment status, and many income supplements and benefits are available to those with disability and poor health, raising problems of reverse causation.13 Educational opportunities available to older cohorts may have been limited, creating a “floor effect,” in which it is difficult to differentiate among the majority whose educational attainment is low.13 Additionally, information may be missing when a proxy respondent has been used, depending on how well the proxy knows the subject. Socioeconomic status is a property of individuals; however, aggregates of such measures can be used to describe the social context in which people live. For example, average income, employment rates, or educational attainment may be useful descriptors when applied to groups of people living in relevant geographic areas such as housing complexes or neighborhoods and may allow for a study of contextual effects on health.14–20

Social Support

Social support refers to the various sources of help and resources obtained through social relationships with family, friends, and other caregivers. Types of social support include emotional (including the presence of a close confidante), instrumental (help with activities of daily living, provided through labor or financial support), appraisal (help with decision making), and informational (provision of information or advice).21 Various measures of social support have been studied, with some tending to be more objective (based on reports of actual use of services and tangible help received in the various domains) and others being more subjective, based on the individual’s perception of the adequacy and richness of the supports to which he or she has access. Social support can also, importantly, be seen as a two-way transaction, with older adults receiving supports in some areas while providing support in others. For example, within spousal relationships, each spouse may have complementary strengths and weaknesses; between generations, older adults may provide care for grandchildren and financial support for adult children while receiving instrumental support.22

Social Networks and Social Engagement

Social networks are the ties that link individuals and groups in social relationships. Various characteristics can be measured, including size, density, relationship quality, and composition.3 Social networks and social support are generally seen as individual-level resources and are measured at an individual level.5,21,23 Through social networks, individuals can access social support, material resources, and various other forms of capital (e.g., cultural, economic, social).24

Social engagement represents an individual’s participation in social, occupational, or group activities, which may include formal organized activities such as religious meetings, service groups, and clubs. More informal activities such as card groups, trips to the bingo hall, and cultural outings to see concerts or visit art galleries can also be considered as social engagement. Volunteerism is often considered separately,3 but can also be seen as an important measure of social engagement.

Social Capital

Social capital is a broad term that has been used inconsistently in the literature, and there is ongoing debate about its nature and measurement. For example, Bourdieu has defined social capital as “the aggregate of the actual or potential resources which are linked to possession of a durable network of more or less institutionalized relationships.”24 This definition is consistent with the idea that social capital is a resource that can be accessed and measured at an individual level, stating that “the volume of social capital possessed by a given agent thus depends on the size of the network of connections he [or she] can effectively mobilize and the volume of the capital … possessed by each of those to whom he [or she] is connected.”24 However, this definition is also consistent with the view that social capital is a property of the relationships within the network; if there are no connections between individuals, there would be no social capital. Coleman has made a similar argument, stating that “Unlike other forms of capital, social capital inheres in the structure of relations between actors and among actors. It is not lodged either in the actors themselves or in the physical implements of production.”25 Coleman also sees social capital as a resource accessible by individuals: “social capital constitutes a particular kind of resource available to an actor.”25

Putnam has defined social capital as “the features in our community life that make us more productive—a high level of engagement, trust, and reciprocity”26—and sees it as “simultaneously a ‘private good’ and a ‘public good’” with both individual and collective aspects.27 To access the private good benefits of social capital, an individual would need to be integrated into a network and have direct connections with other members. However, the public good effects of social capital would accrue to everyone in the community, regardless of their personal connections to others. The public good conception of social capital is shared by others, including Kawachi and colleagues, who see social capital as an ecologic level characteristic that can only properly be measured at a collective level; they noted that “social capital inheres in the structure of social relationships; in other words, it is an ecological characteristic,” which “should be properly considered a feature of the collective (neighborhood, community, society) to which an individual belongs.”5,16,23,28

Measures of social capital are as varied as its definitions and include structural elements (e.g., social networks, relationships, group participation) and cognitive ones (e.g., trust in others, voting behavior, newspaper subscription, feelings of obligation, reciprocity, and cooperation, and perceptions of neighborhood security).3,12,25

Social Cohesion

The concept of social cohesion implies collectivity of definition and measurement. Again, definitions vary, but generally relate to ideas of cooperation and ties that unite communities and societies. For example, Stansfeld has defined social cohesion as “the existence of mutual trust and respect between different sections of society.”29 For Kawachi and Berkman, social cohesion relies on two key features of a society, the absence of social conflict and presence of social bonds.5

Social Isolation

Social isolation is another term encountered in the literature relating social circumstances and health. It is related to ideas of loneliness, reduced social and religious engagement, and reduced access to social supports. It may also incorporate properties of the older adult’s environment, such as difficulty with transportation. As with many other social factors, social isolation can be subjective, as perceived by older adults themselves, such as loneliness, or objective, based on outside measures or assessments by others.

Social Vulnerability

The concept of social vulnerability addresses the understanding that the reason we are interested in the social environment is not merely as a descriptor, but as an attempt to quantify an individual’s relative vulnerability (or resilience or invulnerability) to perturbations in his or her environment, social circumstances, health, or functional status. Older adults’ social circumstances are complex, with multiple factors that may interact in potentially unforeseen ways. A global measure of social vulnerability would thus account for this complexity while providing descriptive and predictive value. A measure of social vulnerability should be broad enough to capture a rich description of the social deficits (or problems) that an individual has, readily and practically measurable in population and clinical settings, responsive to meaningful changes, and predictive of important health outcomes. Ideally, a measure of social vulnerability would incorporate factors that come into play across the continuum, from an individual to a group level. A social ecology framework (Fig. 30-2) is a useful tool for considering social vulnerability as a broad construct, seeing individuals nested within expanding spheres of social influence. This approach considers how social factors at each of these levels—from the individual to family and friends, peer groups, institutions, neighborhoods, and communities, and society at large—contribute to overall social vulnerability.30

How Can We Study Social Influences on Health?

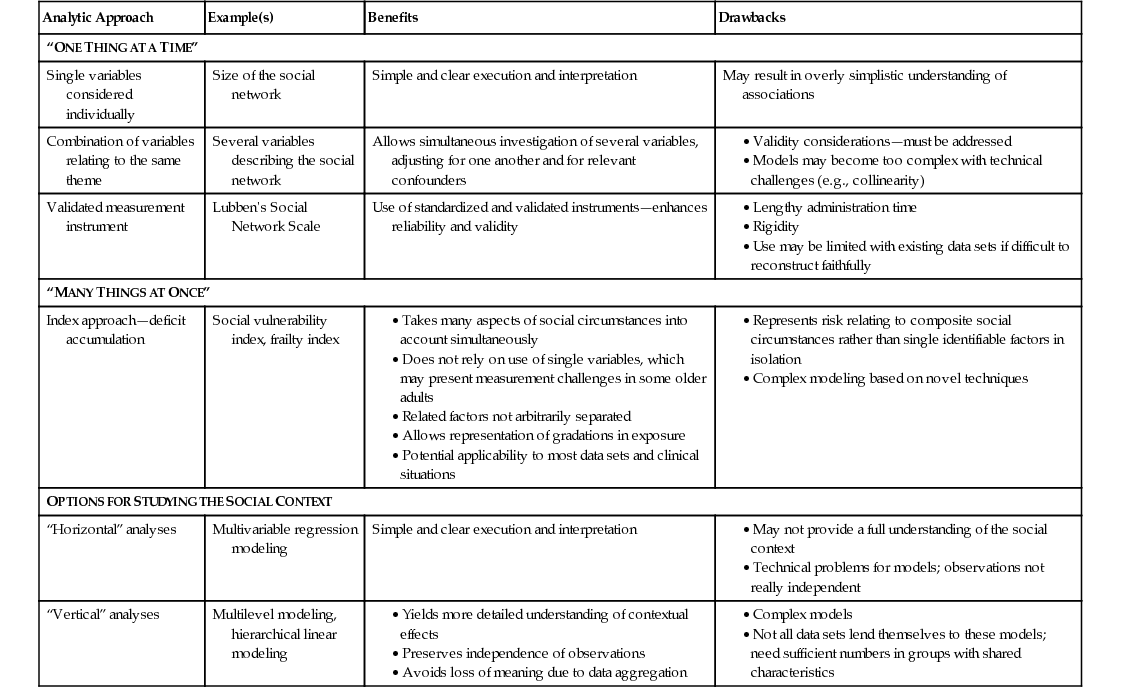

A study of how social factors influence health requires careful consideration of analytic design in relation to the specific questions being asked (Table 30-1). Possible approaches include traditional “one thing at a time” analyses, in which a single social factor (e.g., the social network) is related to the outcome of interest, ideally adjusting for possible confounders in a multivariable model. This approach has certain benefits, chief among them simplicity and clarity in execution and interpretation. For example, it allows for clear statements of important findings such as “An extensive social network seems to protect against dementia.”31 This approach can be carried out using single variables considered individually, a combination of variables relating to different aspects of the same theme (e.g., several variables that relate to the size and quality of the social network), or set instruments that have been previously validated to measure the social factor of interest (e.g., the Berkman and Syme Social Network Index and Lubben Social Network Scale).32 The standardized psychometric properties of such scales add to the reliability and validity of studies that use them, but their use does have drawbacks, including relative rigidity and longer administration time. Their use may also be limited or impossible with existing data sets due to challenges encountered in their faithful reconstruction. Also, considering single variables one at a time may lead to oversimplification of older adults’ complex social circumstances. For example, two older women who live alone may be classified as vulnerable in a study on “living alone.” If one woman is well integrated into the community, with strong social networks and family ties, and the other woman is truly isolated, with no one to count on for help, we understand that they have very different profiles of social vulnerability. Considering single variables one at a time, even with attempts to adjust for other variables in statistical models, risks misclassification of true vulnerability.30,33

TABLE 30-1

Analytic Approaches for Studying Social Influences on Health

| Analytic Approach | Example(s) | Benefits | Drawbacks |

| “ONE THING AT A TIME” | |||

| Single variables considered individually | Size of the social network | Simple and clear execution and interpretation | May result in overly simplistic understanding of associations |

| Combination of variables relating to the same theme | Several variables describing the social network | Allows simultaneous investigation of several variables, adjusting for one another and for relevant confounders | |

| Validated measurement instrument | Lubben’s Social Network Scale | Use of standardized and validated instruments—enhances reliability and validity | |

| “MANY THINGS AT ONCE” | |||

| Index approach—deficit accumulation | Social vulnerability index, frailty index | ||

| OPTIONS FOR STUDYING THE SOCIAL CONTEXT | |||

| “Horizontal” analyses | Multivariable regression modeling | Simple and clear execution and interpretation | |

| “Vertical” analyses | Multilevel modeling, hierarchical linear modeling | ||

Deficit accumulation offers another potential approach to the study of social influences on health. Akin to the frailty index, which readers will find described elsewhere in this volume (see Chapter 15),34 a social vulnerability index, operationalized as a count of deficits relating to many social factors, offers a means of considering an individual’s broad social circumstance and the potential vulnerability of her or his health and functional status. The index has a number of benefits, including the following: (1) the potential to include many different categories of social factors (e.g., SES, social support, social engagement, social capital); (2) the commonly encountered difficulty of embodying social and socioeconomic characteristics using single variables in studies of older adults is alleviated by including consideration of different factors; (3) related factors are not arbitrarily separated into distinct categories for separate analysis; and (4) representation of gradations in social vulnerability is improved compared with consideration of one or a few binary or ordinal social variables. This last point is particularly important, given that studies using the social vulnerability index in two cohorts of older adults have found that no one was completely free of social vulnerability (i.e., no individual had a zero score on the index).33 Use of a deficit accumulation approach to social vulnerability also presents a fifth great benefit, that of scaling. As readers will note elsewhere in this text (Chapters 5, 14, 15, and 16), deficit accumulation can be seen in cells, tissues, animals, and people. Considering the bigger picture of social circumstances, here we can scale this measure of vulnerability up to the societal level.35

In addition to these analytic considerations of how the social factor(s) of interest is (are) measured, incorporating the social context into the analyses can be done in different ways. More traditional horizontal approaches might add a summary variable that describes the individual’s social context (e.g., mean neighborhood income or educational attainment) as a variable or confounder attached to the individual in the multivariable model.18,19 This approach can yield useful findings and has the advantage of simplicity, but some might argue that it does not provide a full understanding of the importance of the contextual variable(s) and that it presents statistical problems in terms of independence of observations—individuals are no longer truly independent if they share these important characteristics of the groups to which they belong. Multilevel (vertical) modeling (e.g., hierarchical linear modeling) is another option; here, the individual is nested within layers of group influence, with collective characteristics treated as attributes of the group rather than of the individual.36 This approach offers the advantage of allowing for a more detailed understanding of the contextual effects, preserving the independence of observations, and not losing information, as occurs when data are aggregated.36

The consideration of contextual or group-level variables such as neighborhood and community characteristics is particularly relevant to the study of how social factors affect health because many social factors are properties of the groups or communities in which individuals live and may be best measured on a group level. As we have seen, there is active debate about whether social capital is a property of individuals or of groups.3,11 Most theories of social capital are consistent with the idea that it is a property of relationships between individuals and within societies, rather than residing within individuals per se. The heart of the issue, which continues to divide theorists, is whether social capital is a resource that an individual can be said to draw on and thus, in practical research terms, whether it can legitimately be measured at an individual level.

This debate has clear implications for the design and interpretation of research studies that aim to investigate how social factors influence health; valid and useful findings can rest only on sound theoretical foundations. In this regard, a second distinction may be helpful; the answer may depend on whether the question applies to where social capital exists (is it a property of individuals or of relationships?) or to how it is measured and accessed.11 Practically speaking, measurement issues and data availability may strongly influence analytic design. The issue of how social factors should be studied in relation to older adults’ health is therefore ideally guided by a balance of theoretical considerations and analytic pragmatism.

Successful Aging

This concept has been the subject of numerous enquiries in the academic literature and popular press.37–39 Definitions of successful aging vary and generally fall into psychosocial and biomedical camps, with contributory factors that include physical functioning, social engagement, well-being, and access to resources.38 Psychosocial conceptualizations emphasize compensation and contentedness, in which biomedical definitions are based on the absence of disease and disability.40 The concept of successful aging recognizes that the aging process is variable, and that how older adults adapt to later life changes associated with aging influences how successfully they will age. Ideally, research into this area would identify potentially modifiable factors are at play that help some age better and more successfully than others.

There is a potential downside to the idea of successful aging: if successful aging is applied as a value judgment, it may be at the cost of blaming and further marginalizing the so-called unsuccessful agers, those who are not so fortunate as to have the good health and functional status that might allow them to be doing aerobics at the age of 102 years or volunteering with “the old people” at 99 years of age.37 Such stereotypes, based on rare aging successes and on the undercurrent of ageism that is common in our society, also influence the portrayal of older adults in the popular media. Positive and negative stereotypes run the risk of perpetuating the marginalization of the most vulnerable older adults, regardless of whether their unsuccessful aging is implied or emphasized.37

Another way to think about successful aging is to consider individuals who overcome their expected trajectory in the natural history of decline for a given level of frailty. Work with the frailty index has shown that trajectories of decline are established early, and that such declines are well predicted using mathematical models.41,42 However, there are some older adults who improve or transition to lower levels of frailty—who are able to “jump the curve” from their own predicted course and outcomes to attain the outcomes that would be expected for people with a lower baseline level of frailty. This might be a useful subgroup in which to study predictors and correlates of this successful aging.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree