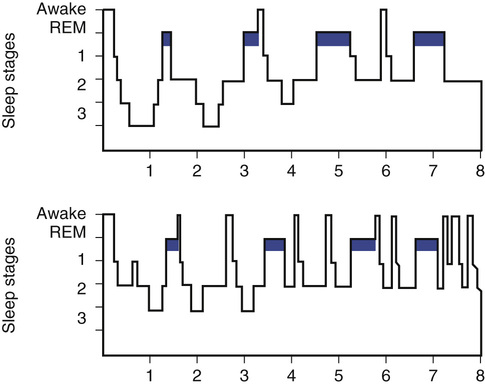

Roxanne Sterniczuk, Benjamin Rusak Getting adequate sleep and maintaining normal daily sleep-wake rhythms are important to sustaining good lifelong physical and mental health and reducing the risk of disease development. Acute sleep loss leads, for example, to disruption of endocrine function and glucose metabolism.1–3 Chronic sleep loss and daily rhythm disruption also lead to numerous negative long-term health consequences,4 including increased risk for obesity,5 cardiovascular disease,6 and type 2 diabetes.7 In addition, disrupted sleep-wake and circadian rhythms (e.g., as a result of chronic shift or night work) have been linked to an increased risk for developing cancer8–10 and for resistance to cancer treatments.11 Some of the negative consequences of sleep loss may be related to its impact on immune system function. Disturbed or short sleep weakens immune system function,12,13 which can lead to impaired healing and recovery,14–16 as well as inadequate immune system responses to vaccinations.17 Increased risk of metabolic diseases, weakened immune responses, and inadequate tissue repair are in turn associated with accelerated health deficit accumulation and increasing frailty in older adults.18,19 Sleep has also been shown to be involved in brain plasticity and consolidation of newly acquired information, so disrupted sleep can interfere with learning and memory.20,21 Sleep has also been proposed to play an important role in facilitating clearance of the metabolic products of neuronal metabolism, including the substance most closely linked to the development of Alzheimer disease, β-amyloid.22,23 These physiologic effects of sleep loss may be the basis for findings of increased risk for cognitive decline and ultimately for the development of Alzheimer disease in those with sleep problems.24,25 Several changes in sleep patterns have been associated with aging, including an advance in the timing of sleep onset and waking to earlier clock times, more disrupted sleep, reduced slow-wave sleep with more light sleep, and increased daytime napping.26–28 As a result, more than 80% of those older than 65 years report some degree of disrupted sleep.29 Older adults also have more difficulty adjusting to changes in daily rhythms resulting from travel or shift work schedules.30 Although the types of sleep shown, degree of sleep continuity (i.e., sleep maintenance or lack of interruption by wake episodes), and distribution of sleep across the 24-hour cycle change with age, total daily sleep time remains relatively stable in healthy aging, with those 60 years of age and older sleeping an average of 6.5 to 7 hours a day.31,32 Sleep changes during aging may be related to the disruption of sleep regulatory mechanisms in the brain.33,34 However, it is important to bear in mind that many medical conditions that disrupt nocturnal sleep, and consequently can provoke daytime sleepiness, also increase in frequency with age. These include sleep-related breathing disorders (e.g., sleep apnea), pain syndromes (e.g., arthritis), prostatism in men, and menopause-related hot flashes in women. In addition, sleep may be disrupted early in the prodromal stages of neurologic diseases (e.g., Parkinson and Alzheimer diseases).25,35 These and other potential contributors to sleep disruption in older adults should be ruled out before considering whether changes intrinsic to sleep regulatory or circadian mechanisms are implicated in these features.36 One impact of the circadian system on sleep is to promote sustained waking during the day and sleep at night; a reduction in the strength of this circadian impact can contribute to increased sleep disruption and redistribution of sleep during the 24-hour day. There is evidence from animal models and human studies that the amplitude of oscillation of the circadian pacemaker in the hypothalamic suprachiasmatic nucleus is reduced during aging.37–39 In addition, the molecular mechanisms responsible for generating these daily rhythms may be disrupted with age.40 Aging also affects various physiologic rhythms that influence sleep, such as body temperature, melatonin secretion, and fluctuations in other neuroendocrine systems (e.g., declining secretion of luteinizing, growth, and thyroid-stimulating hormones; lower serotonin levels). Although older adults spend more time in bed than younger adults, they experience pronounced deterioration in the quality of sleep, as measured by changes to sleep architecture41 (Figure 108-1). Sleep tends to become shallower and lighter with advancing age, and there are fewer sleep spindles and smaller amplitude K complexes observable during non–rapid eye movement (REM) stage 2 sleep (N2), as measured by electroencephalography (EEG). One of the most profound changes observed in older adults is a reduction in the number and amplitude of electroencephalographic delta waves, which corresponds to a significant decrease in the percentage of time spent in slow-wave sleep or non-REM stage 3 sleep (N3, formerly divided into stages 3 and 442), or even the virtual absence of this sleep stage in the oldest cohorts.43,28 A meta-analysis of 65 studies has demonstrated that there is a significant decrease in total sleep time, sleep efficiency (time spent asleep as a proportion of the time spent in bed), percentage of slow-wave sleep, and REM sleep latency, from young adulthood to about age 60 years, after which only sleep efficiency appears to continue to decrease. These changes are accompanied by an increase in the percentage of non-REM stage 1 sleep (N1), the lightest stage of sleep characterized by low-voltage, mixed-frequency waves, as well as N2. An increase in sleep latency and time spent awake after sleep onset also occurs.28 Many reports have suggested as much as a 50% reduction in REM sleep in older as compared to younger adults.28,44 However, when the effects of mental and physical illnesses are taken into consideration,36 the percentage of REM sleep is relatively well preserved from age 60 years onward.28 Insomnia is usually defined as inadequate or unrefreshing sleep and is characterized by self-reports of difficulty falling or staying asleep, typically accompanied by increases in sleepiness and functional impairment during the day. It is the most common sleep complaint in most age groups, including older adults45 (Table 108-1). Complaints of insomnia are often,29,46,47 but not always,48,49 reported to increase with age. Women are more likely to complain of insomnia, especially during and after menopause, and this gender difference appears to increase after the age of 65 years. Insomnia symptoms tend to persist over time,31,32,50 with early-morning awakenings and disrupted sleep continuity during the night being highly associated with older age groups; younger adults tend to exhibit greater difficulty initiating sleep. TABLE 108-1 Common Sleep Disorders in Older Adults Difficulty falling or staying asleep Early-morning awakenings Disrupted sleep continuity at night Involuntary repetitive leg jerks that occur at 20- to 40-sec intervals Occurs during non-REM sleep Irresistible urge to move one’s legs due to a restless crawling sensation or pain Associated with sleep onset Acting out elaborate movements during sleep (e.g., punching, kicking, yelling) Occurs during REM sleep Sleep-related respiratory disorders encompass those conditions that cause abnormal respiratory events during sleep, ranging from mild snoring to a reduction (hypopnea) or complete cessation of airflow (apnea).51 Obstructive sleep apnea is one of the most common sleep disorders. It is caused by relaxation and subsequent collapse of muscles in the back of the throat, causing obstruction of the upper airway. The increased prevalence of sleep apnea in older adults, which has been reported to be as high as 62% in those older than 60 years,52 may be due to the increased occurrence of obesity, age-related decline in muscle tone, or impaired pharyngeal sensory detection thresholds. Sleep apnea often goes unrecognized in older adults because the overt symptoms that are reported—fatigue, daytime sleepiness, morning headache, mood changes, poor concentration, or memory loss—tend to be attributed to other comorbidities or to the aging process. Peaking at age 50 to 60 years, snoring is also a frequent complaint of older adults. Interestingly, the prevalence of snoring has been shown to decrease after the age of 75 years, possibly reflecting a survivorship effect. Snoring may be related to various comorbidities, especially obesity and sleep-disordered breathing, that ultimately contribute to premature death in this age group. Narrowing of the upper airway, which contributes to snoring, is also associated with the many health consequences of sleep-disordered breathing, including hypertension, heart disease, and stroke.53–55 Periodic limb movements are repetitive leg jerks or kicks that occur specifically during sleep. They can range from subtle contractions of the ankle or toe muscles to dramatic flailing of the limbs. These movements often occur during N2, resulting in sleep disruption and excessive daytime sleepiness. Its prevalence increases with age and can be found in as many as 45% of community-dwelling older adults.56 Restless legs syndrome is commonly comorbid, and often confused, with period leg movement disorder. It is characterized by uncomfortable, restless, crawling sensations in the legs, creating an irresistible urge to move or walk, typically when one first goes to bed. These sensations can contribute to sleep-onset insomnia as well as disrupted sleep. The condition is also more prevalent in older adults, occurring in up to 35% of those older than 65 years, with about twice as many women being affected. Restless legs syndrome has been associated with iron deficiency and abnormal dopaminergic signaling; it can be treated with interventions aimed at these features.57 REM sleep behavior disorder involves movement during dreams due to the absence of muscle atonia, which normally occurs during REM sleep.58 Individuals may engage in punching, kicking, yelling, or even more elaborate behaviors during REM sleep; the behaviors are often aggressive in nature and can injure the sleeper or bed partner. This condition is relatively rare in the general population (0.5%) and occurs almost exclusively in men older than 60 years.59,60 The cause of REM sleep behavior disorder is unclear, but has been strongly linked to the subsequent development of neurodegenerative diseases known as synucleinopathies, including Parkinson disease, Lewy body dementia, and multiple system atrophy.61 Despite the characteristic sleep changes that are experienced by older adults, these typically age-associated sleep disturbances may not be an inevitable part of the healthy aging process, but rather a consequence of other changes that accompany aging. Insomnia, in particular, appears to be a major factor contributing to the increase in age-associated sleep complaints.62–64 However, the decreased ability to fall asleep or maintain sleep once initiated is frequently linked to a comorbid health condition. There is an increased risk for various medical and psychiatric conditions (e.g., depression, diabetes, arthritis, chronic pain, loss of bladder elasticity) during aging, which may indirectly disturb sleep.41 In addition, pharmacologic treatments for these conditions (e.g., antidepressants, β-blockers, diuretics, corticosteroids) are often not recognized as factors that may contribute to sleep disturbances. Although one study has reported that an extensive health assessment can identify medical conditions that account for most sleep complaints in older adults,36 an estimated 10% to 16% of community-dwelling adults older than 65 years still report chronic (primary) insomnia in the absence of an obvious precipitant.65,66 Frailty can be conceptualized as an increasing vulnerability to poor health outcomes (i.e., disability, institutionalization, mortality) as a result of accumulating age-associated declines in physiologic systems; because health deficits increase with age, so does frailty.67,68 Little is known about the relationship between frailty and sleep or about the consequences of sleep disturbances in frail populations.69,70 In addition, the sparse literature on this topic has focused primarily on community-dwelling older adults.25,71–74 Daytime drowsiness is associated with a higher level of frailty,74 and older adults who exhibit poor subjective sleep quality, increased nighttime waking, and greater nighttime hypoxemia have been found to be at higher risk for increasing frailty about 3 years later.73 Those with excessive daytime sleepiness, frequent nighttime awakenings, and sleep apnea may also be at greater risk for mortality up to about 3 years later, whereas short sleep duration and prolonged sleep-onset latency are not clearly associated with increased frailty or risk of early death.73 Given that sleep disturbances are associated with poorer health, frail individuals, who are already more vulnerable to the accumulation of stressors, may also be affected by the consequences of sleep impairment to a greater extent than healthy older adults (e.g., responses to sleep medication, impact of insomnia or other sleep disorders). Alterations to the sleep-wake cycle may have prognostic utility in predicting future decline in health and increasing frailty. If so, then treating specific sleep disorders in frail adults may reduce the rate of acquisition of deficits and development of dependency. Patients who are especially susceptible to the adverse effects of accumulating deficits are those in the intensive care unit (ICU). Sleep disturbance and insomnia are common in ICU patients,75,76 in particular in older adults.77 Sleep disruption in the ICU has also been linked to impaired healing and recovery, and even to increased mortality.78,79 In addition, up to 41% and 96% of older patients in the general and surgical wards, respectively, are prescribed sedative-hypnotic drugs. As discussed later, these drugs tend to have greater negative effects in older adults and may interact adversely with other medications that may also be prescribed for them. Several analyses have concluded that the risk of adverse health outcomes from sedative agents does not justify the small benefit achieved.80,81 It remains unclear how age and premorbid frailty levels affect sleep quality in older adults who are treated in the ICU.82 Determining how sleep quality in this environment affects health outcomes, such as cognitive decline and mortality, will help provide guidance about appropriate treatments for vulnerable older patients in this high-risk situation.

Sleep in Relation to Aging, Frailty, and Cognition

Sleep and Health

Sleep and Circadian Rhythm Disturbances in Older Adults

Changes in Sleep Architecture During Aging

Non–Rapid Eye Movement Sleep

Rapid Eye Movement Sleep

Sleep Disorders in Aging

Late-Life Insomnia

Sleep Disorder

Prevalence

Characteristic Features

Late-life insomnia

Up to 50% in those > 65 yr

Obstructive sleep apnea

Up to 62% in those > 65 yr

Five or more episodes/hr of reduction or complete cessation of airflow

Periodic limb movements

Up to 45% in those > 65 yr

Restless legs syndrome

Up to 35% in those > 65 yr

REM sleep behavior disorder

0.5% of those in the general population

Sleep-Disordered Breathing

Periodic Limb Movements in Sleep and Restless Legs Syndrome

Rapid Eye Movement Sleep Behavior Disorder

Sleep Disturbance and Comorbidity

Sleep and Frailty

Sleep in Critically Ill Older Adults

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Sleep in Relation to Aging, Frailty, and Cognition

108