Chapter 13

Skin trauma

Introduction

The ageing process causes changes in the structure and function of the skin, which make older adults more vulnerable to skin tears, lacerations and pressure injuries following falls or other trauma. Burns are more likely to be deeper and of a wider surface area, with markedly higher morbidity and mortality.

Any break in skin integrity, however minor, may lead to significant complications. The care of the older person’s skin, both in health and following injury, should be seen as a priority.

Background

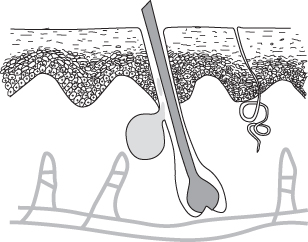

Figure 13.1 highlights the skin changes that occur with ageing.

| Epidermal thinning results in reduced epidermal turnover and altered microcirculation, which delay healing. Lacerations are more likely following mild mechanical forces Thinner subcutaneous tissue reduces protection against pressure injuries, fractures and hypothermia | Flattening of dermo–epidermal junction Shearing forces are likely to cause skin tears  Figure 13.1 Age-related skin changes. | Reduction in number of sweat glands leading to dry, itchy and fragile skin Fragile vascular capillaries leading to ecchymosis and haematoma development following minor trauma |

| Dermal thinning results in a reduction in blood vessels, nerve endings and collagen, leading to reduced elasticity and strength of skin. There is also altered temperature control, reduced sensation and moisture retention. Burns are more likely to cause full dermal thickness injuries. | ||

In addition to the skin changes mentioned above, comorbid conditions and medications can lead to poor wound healing. The presence of localised oedema, poor circulation or neuropathy may result in the development of chronic wounds or ulceration.

History and examination

History taking should establish the mechanism and timing of the injury, along with a full assessment as per the guidance in Chapter 8. Document the presence of diabetes, anaemia, malignancy and cardiovascular disease as all these conditions may complicate wound healing. Medications implicated in delayed wound healing include corticosteroids, other immunosuppressive agents, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and anticoagulants. Note any history of chronic wounds or ulceration after previous injuries.

Assess pain and consider non-pharmacological methods of analgesia, such as dressings, elevation, and splinting, as well as analgesic medication (Chapter 3).

Box 13.1 highlights the important aspects to document when examining a skin wound in the older adult.

Tetanus status

Tetanus remains a rare condition, but the older patient is most at risk. The combination of waning immunity with ageing and delayed presentation or poor initial wound management contributes. Older women and those over 80 are at higher risk: men are more likely to have received vaccination as part of military service. Studies have demonstrated inadequate antibody titres in over 50% of older patients (1, 2). Immunisation history may be unreliable and extra precautions should be taken. Tetanus-prone injuries include a wound or burn sustained over 6 hours prior to treatment; puncture wounds; wounds with significant devitalised tissue including pressure ulcers; wounds in contact with soil or manure and evidence of sepsis.

Patients with tetanus-prone wounds who do not have a clear history of at least three tetanus vaccinations should be given tetanus immunoglobulin in addition to a tetanus vaccine (3). Consult local protocols in other circumstances.

Specific injuries

Skin tears

Skin tears occur as a result of friction or sheering forces causing separation of skin layers. Partial thickness tears result from separation of the epidermis from the dermis and full thickness tears from the separation of the dermis from underlying subcutaneous tissue (4). Skin tears commonly occur on extremities, particularly on the dorsal aspect of the hand or forearm, the shin, as well as the back and buttocks. Skin tears can be classified according to the presence of skin loss or a skin flap. A suggested classification is detailed in Table 13.1.

Table 13.1 STAR skin tear classification system (5)

| 1a | A skin tear where the edges can be realigned to the normal anatomical position (without undue stretching) and the skin or skin flap colour is not pale, dusky or darkened |

| 1b | The edges can be realigned to the normal anatomical position (without undue stretching) and the skin or skin flap colour is pale, dusky or darkened |

| 2a | The edges cannot be realigned to the normal anatomical position and the skin or skin flap appears well perfused |

| 2b | The edges cannot be realigned to the normal anatomical position and the skin or skin flap colour is pale, dusky or darkened |

| 3 | The skin flap is absent, and there is loss of skin |

Box 13.2 summarises the management of skin tears. Most skin tears will heal well with conservative treatment. When choosing a non-adherent dressing, it is important to maintain a moist wound environment while controlling the exudate. Some centres routinely use antibiotic ointment for wounds and burns, although the evidence base is limited (6). Routine oral antibiotics are not indicated unless there is significant contamination or the wound resulted from a human or animal bite.

Scalp and face lacerations

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree