Kacper K. Pierwola, Gopal A. Patel, W. Clark Lambert, Robert A. Schwartz Aging affects all organ systems, including the integument. Cell replacement, sensory perception, thermal regulatory function, and immune defense systems are among the many components that are compromised. The skin appearance changes, depending on environmental and genetic factors. The psychosocial impact, including cosmetic disfigurement and social stigma, in addition to vulnerability to skin disease, must be addressed in older patients. The role of the physician is to diagnose, treat, and guide patients through this visible component of aging while preventing avoidable disease. The U.S. population older than 65 years has been greatly expanding. Skin complaints constitute a significant and growing portion of geriatric ambulatory patient visits. A 2005 U.S. study demonstrated that 21% of all patients seen by family practitioners had a skin problem. It was their primary complaint 72% of the time.1 Also in 2005, the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS) showed that the number of outpatient visits was highest in the 45- to 64-year-old age group, a shift up from the 1995 survey, suggesting increasing medical use by the baby boomer population, which is now entering the 65 years and older bracket.2 A more recent 2012 NAMCS survey has further supported this shift in demographics.3 Among all patient age groups, 1 in 20 visits to an outpatient office are of skin, hair, or nail concern.2 Diseases such as cutaneous melanoma are on the rise, with lifetime risks shifting from 1 in 250 in 1980 to 1 in 65 in 2002 based on a U.S. population study.4 These data emphasize the importance of skin disease recognition in older adults.5 Skin cancer, for example, is often preventable and, with early diagnosis, can be 100% curable. Also, the role of cosmetic services and the impact on psychosocial well-being that can be traced to skin disease is of added concern. A complete medical history is desirable for the skin disease patient, regardless of age. One should pay attention to medicines or chemicals used, including topical, systemic, cosmetic, or complementary and alternative agents. The duration of a complaint, previous therapy, close contacts, and patient opinion on cause may assist or obfuscate diagnosis and treatment. Hygiene, including bathing and laundering habits, should be assessed. Geriatric patients should undergo a thorough skin evaluation under good lighting. Older patients often have trouble with medication compliance. Dermatologic treatments are further challenging because of their frequent topical nature. Patients may need to apply creams on difficult to reach areas (e.g., feet, back) or may be immobilized. Shampooing, showering, or complicated treatment regimens can confuse and challenge geriatric patients. The clinician needs to be aware of all these barriers and accommodate accordingly. The older patient population’s chief complaint is often of a pruritic (itchy) rash or lesion that turns out to be an eczematous disease. The prevalence of eczema is between 2.4% and 4.1% in the U.S. population.6 In older adults, natural aging of the skin predisposes patients to eczematous diseases. In a Turkish study of more than 4000 patients, eczematous disorders constituted nearly 22% of diagnoses in the 65- to 74-year-old age group.7 Xerosis describes rough or dry skin, which is seen in almost all older adults. Conditions of low humidity, such as artificially heated rooms, especially forced hot air heating, exacerbate this condition. Xerosis is actually a misnomer, because water is not absent throughout the entire thickness of the skin. There is only diminished hydration in the superficial corneum.8,9 Xerosis has also been misclassified as a sebaceous gland disorder. Although sebaceous gland activity decreases with age and thus depletes the skin’s moisture, it only plays a partial role in xerosis development.10 Other factors include an irregular epidermal surface caused by maturation abnormalities. Deficits in skin hydration and lipid content impair normal desquamation, leading to the formation of the skin scales that characterize xerosis. Furthermore, old age results in altered lipid profiles and decreased production of filaggrin, which are filament-associated proteins that bind keratinocytes. Both factors contribute to xerosis.9 Xerosis may appear scaly, with accentuated skin lines, often occurring on the anterior legs, back, arms, abdomen, and waist. The scales are a result of epidermal water loss, and focal dryness may be deep enough to cause bleeding fissures. Superimposed pruritus is possible, leading to secondary excoriations, inflammation, and lichen simplex chronicus.9 Allergic and irritant contact dermatitis may also complicate xerosis. Secondary infection may follow a break in the skin barrier.11 Xerosis is also a secondary feature of many of the conditions discussed in this chapter. Untreated xerosis progresses to flaking, fissuring, inflammation, dermatitis, and infection. Topical emollients make dry skin more comfortable and avoid such complications. Alpha-hydroxy acids (e.g., 12% ammonium lactate) are helpful because of their keratolytic nature, although some patients report stinging and irritation.12 Formulations containing ammonium lactate or other alpha-hydroxy acids help restore barrier function and improve xerosis.13 Liberal use of moisturizers throughout the day is recommended. Topical steroids (classes III and VI) are recommended in moderate to severe cases, along with antipruritics for symptomatic itching. Further recommendations include decreasing hot water baths, reducing use of soap or harsh skin cleansers, avoiding rough clothes on the skin, using a humidifier in a dry environment, and adding emollient substances, such as oatmeal, to bathwater. Simple xerosis is a common cause of pruritus in older adults. Asteatotic eczema is a dermatitis superimposed on xerosis that often flares in the winter. It is dry scaly skin, sometimes in extreme cases resembling cracked porcelain, with bleeding from damaged dermal capillaries. The cracked porcelain, or so-called crazy paving, pattern is best termed eczema craquelé.14 Asteatotic eczema is a common condition on the shins of geriatric patients, although it is also seen on other regions of the body. There are several associations of asteatotic eczema—one related to hard soaps, one to corticosteroid therapy, one to neurologic disorders, and an idiopathic form often located on the shins of older patients. Prevention is the key to controlling this problem. Contributing factors include cleansers used, frequency of showers, diet, medications, and temperature exposure. Specifically, patients should reduce the use of hot showers and irritant detergents. Creams, humidifiers, and topical steroids can improve the effects of asteatotic dermatitis.14 Alcohol-based lotions feel good just after application but eventually cause increased dryness and should be avoided. Seborrheic dermatitis is a chronic condition that typically manifests as an erythematous and greasy scaling eruption, usually affecting areas with abundant sebaceous glands, including the scalp, ears, central face, central chest, and intertriginous spaces.15 When present in the scalp, it tends to cause flaking known as dandruff. It may also appear as marked erythema over the nasolabial fold during times of stress or sleep deprivation. Although the prevalence of seborrheic dermatitis is approximately 5% in the general adult population, estimates in those aged 65 years and older report a range from 7% to as high as 67% in institutionalized patients.16–18 Seborrheic dermatitis is also found in greater frequency with neurologic conditions such as Parkinson disease, a concern in the geriatric population.19 Facial nerve injury, spinal cord injury, syringomyelia, and neuroleptic treatment are also associated with seborrheic dermatitis. The pathogenesis of seborrheic dermatitis, although controversial, has been attributed to the yeast Malassezia species (e.g., Malassezia furfur, Malassezia ovalis; formerly known as Pityrosporum).20 This yeast is a normal resident in more than 90% of healthy adults, but when overgrown it can be proportionally related to the severity of seborrheic dermatitis. Treatment options against Malassezia spp. have been effective for seborrheic dermatitis, supporting a causal relationship. Antifungals along with topical steroids are used, such as ketoconazole cream or shampoo and hydrocortisone valerate cream.15 Furthermore, topical ketoconazole has inherent antiinflammatory properties. One classic study comparing these two agents determined that 2% ketoconazole cream was 80.5% effective in resolving seborrheic dermatitis, as opposed to 94.4% efficacy with 1% hydrocortisone cream.21 Although not as effective as hydrocortisone, ketoconazole serves as an effective steroid-sparing agent. The calcineurin inhibitors tacrolimus and pimecrolimus are macrolide immunosuppressants that are alternative agents for use on the face, again to reduce the use of steroids in this sensitive area. A 2008 randomized prospective controlled study comparing 1% pimecrolimus cream and 2% ketoconazole cream showed equal efficacy between the two, but there were greater side effects with pimecrolimus.22 Side effects included burning, itching, and redness. Both tacrolimus and pimecrolimus have a black box label by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) warning of skin cancer or lymphoma formation in some patients using this drug, although an established link remains controversial.23 Shampoos with ketoconazole, selenium sulfide, salicylic acid, zinc pyrithione, or tar are also effective for relieving seborrheic dermatitis in hair-bearing regions.24 Older patients often experience localized or generalized pruritus, which can be severe. The cause of itching in older patients is often difficult to determine. Renal, hematologic, endocrine, cholestatic, allergic, infectious, and malignant causes all potentially contribute to the older patient’s itch. Entities causing pruritus include the following25,26: Some of these are addressed here. Physiologically, specific C-fiber neurons that terminate at the dermoepidermal junction transmit the itch sensation to the brain. These fibers possess receptors sensitive to histamine, neuropeptide substance P, serotonin, bradykinin, proteases, and endothelin. Rubbing or scratching further stimulates these receptors.27 As the itch and scratch cycle progresses, the skin is driven to a point of barrier function compromise, which is worrisome in older patients with limited means of self-care. Pruritus is one of the most distressing concerns of a patient suffering from cholestasis. The exact cause of pruritus in this disease is unknown, although an altered role of opioid receptor function has been suggested.28 Treatment of the underlying disease process often resolves itching. However, some diseases, such as primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC), cannot easily be cured. Ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) treatment for PBC often does not resolve the patient’s pruritus.29 Cholestyramine, rifampin, naloxone, and phenobarbital are other agents used for pruritus, all of which have substantial side effects in older adults.30 Generalized pruritus is recognized as a key marker of underlying malignancy, particularly lymphomas and leukemias.31 Generalized pruritus is noted in up to 30% of patients with Hodgkin disease and may be the only presenting symptom.32,33 Pruritus is also a key feature of multiple myeloma, polycythemia rubra vera, Waldenström macroglobulinemia, and malignant carcinoid.34 Pruritus is best resolved by identifying and treating the underlying systemic cause. Unfortunately, nonspecific therapies must often be used for older patients with an atypical disease presentation. Emollients are valuable interventions, regardless of suspected cause, because some level of pruritus exacerbating xerosis is present in most older patients. Topical use of alcohol, hot water, or harsh soaps and scrubbing must be discouraged. Proper humidity, cool compresses, nail trimming, and behavior therapy may all improve the itch and scratch cycle.27 Topical anesthetics such as benzocaine and dibucaine have been used for relief. A trial of oilated soap and antihistamines may also be helpful before an invasive workup, including hematologic studies, imaging for malignancy, skin biopsy, skin scrapings, skin culture, and HIV testing.34 Antihistamines should be used with caution because they are not universally effective and may cause sedation in the vulnerable and often highly medicated older patient. Stasis dermatitis is a common condition affecting 15 to 20 million patients older than 50 years in the United States.35 It often presents as a circumscribing dermatitis around the calf and ankle in patients with chronic venous insufficiency and venous hypertension. However, any body area constantly under pressure against a hard surface may be affected. Pitting edema may be present, in addition to loss of hair, waxy appearance, and yellow-brown pigmentation.36 If untreated, stasis dermatitis may progress to a chronic nonhealing wound, with erythema and oozing. Stasis dermatitis results from poor function of the deep venous system in the legs, which leads to backflow and hypertension in the superficial venous system.37 Often, both lower legs show stasis dermatitis. An associated self-perpetuating cutaneous inflammatory response follows.37 The workup includes venous Doppler studies to identify flow in the involved venous plexus. Several treatment approaches are useful in resolving stasis dermatitis. Compression of the legs to control superficial venous hypertension is critical. This can be achieved by the use of Unna boots, compression stockings, or elastic wraps. In one study of more than 3000 patients, those with stasis dermatitis had a compliance of 46% for the use of compression stockings.38 Leg elevation 6 inches above the level of the heart during sleep also improves blood flow. Topical treatments include corticosteroids and the calcineurin inhibitors, pimecrolimus and tacrolimus. Corticosteroids have an associated risk of tachyphylaxis and must be used carefully because of the high risk of infection in these patients.39,40 Topical antibiotics such as bacitracin, neomycin, or polymyxin B may be added if there is evidence of skin barrier compromise and infection. For more information on stasis ulcers, see Chapter 37. Patients with a long history of stasis dermatitis with chronic lymphedema due to nonfilarial causes such as infection, surgery, radiation, neoplastic obstruction, obesity, portal hypertension, or chronic congestive heart failure may develop a condition known as elephantiasis nostras verrucosa (ENV).41 Physical examination may show dependent edema with hyperkeratosis and lichenification, papillomatous plaques, crusting, cobblestone-like nodules, and erythema of the affected area (Figure 94-1).42,43 Management of ENV is similar to that of stasis dermatitis because it relies on treating the underlying condition of lymphedema using limb elevation, skin hygiene, lymphatic drainage, compression bandages, support stockings, and lymphatic pumping as well as weight loss and infection control.44 Cherry angiomas, also known as cherry hemangiomas or Campbell de Morgan spots, are the most common vascular proliferations of the skin and are nearly ubiquitous after the age of 30 years. They appear as firm, smooth, red papules ranging in size from 0.5 to 5 mm. They may also appear as a myriad of tiny spots resembling petechiae. Although patients may be concerned with a new cherry angioma, the condition is benign. Cosmetic concern may merit electrocautery or laser coagulation treatment.45 Venous lakes are dark blue to violet-colored papules that occur on sun-exposed areas of older patients. They are compressible lesions common on the face, lips, and ears. The differential diagnosis includes blue nevus and malignant melanoma. Venous lakes are benign lesions and treatment is for cosmetic purposes or bleeding. Electrodesiccation, excision, or lasers may be used to remove venous lakes.46 Herpes zoster (shingles) is a reactivation of the varicella zoster virus, the causative agent of varicella. It is a significant ailment of older adults, ranging from 690 to 1600 cases/100,000 person-years in those 60 years and older.47–49 The varicella zoster virus remains latent in the dorsal root ganglia of the nervous system after its initial infection usually resolves in childhood.50,51 A weakened or impaired immune system is thought to precede reactivation, so underlying conditions such as lymphoma, leukemia, and possible HIV infection should be considered. Local steroid injection has also been associated with a herpes zoster flare.52 Herpes zoster begins as a prodromal sharp pain localized to a dermatomal region, followed by a rash and vesicular eruption (Figure 94-2). Itching, burning, and weakness of muscles associated with the involved nerve may be noted. More than 20 vesicles outside of the primary dermatome suggest disseminated zoster, as may be seen in immunocompromised patients53 or patients with granulocytic lesions. The long-lasting pain of zoster may be mistaken for gallbladder, kidney, or cardiac pain, depending on location. Chronic pain or chronic pruritus localized to the dermatome may follow. This is known as postherpetic neuralgia (PHN) or postherpetic itch, respectively.54 Herpes zoster is diagnosed by a Tzanck smear of a sample scraped from the base of an intact vesicle. The appearance of multinucleated giant cells may indicate a herpetic infection. Treatment of herpes zoster includes early antiviral therapy, within 72 hours of onset. Acyclovir is a safe but variably efficacious agent, although famciclovir is also used. In one double-blind, randomized group study of 55 patients, it was found that famciclovir was well tolerated and had a more favorable adverse event profile than acyclovir.55 Valacyclovir is an L-valine ester form of acyclovir and is converted to acyclovir in vivo. It provides three to five times the oral bioavailability of acyclovir and has been shown in clinical trials to reduce pain severity better.56 In 2006, the FDA approved the use of a live zoster vaccine (Zostavax) for the prevention of shingles in immunocompetent patients older than 60 years. According to the multicenter Shingles Prevention Study, vaccine administration reduces the incidence, burden, and PHN complications in older patients.57 Oral antibiotics covering staphylococci and streptococci are used to control secondary infection.50 PHN is most evident in older adults, and 10% to 18% of zoster patients develop this neuralgia, according to a community-based U.S. study.58 Treatment is more challenging for PHN and requires the concomitant use of pain medication, such as topical capsaicin. The prompt prescription of analgesia, recommended when zoster is still active, often reduces long-term negative outcomes for PHN.59 Scabies is among the oldest recognized infections to occur in humans, with more than 300 million yearly cases detected worldwide.60,61 A U.K.-based study showed an incidence of 788/100,000 person-years of scabies.62 Risk factors include nursing home residence, especially older (>30 years) and poorly staffed (>10 : 1 bed–to–health care provider ratio) institutions. The causative agent for scabies is the mite, Sarcoptes scabiei, whose life span is about 1 month. Transmission requires direct skin contact or indirect contact with bedding or clothing. Once the pregnant female mite is on a new host, she digs into the skin to lay eggs. The eggs, saliva, feces, and the mites themselves lead to a delayed type IV hypersensitivity reaction from 2 to 6 weeks after contact so that at onset, multiple lesions are typically seen. These immune reactions lead to intense pruritus. In previously infected patients, the immune system response may present in 1 to 4 days after contact.63 Scabies manifests as papules, pustules, burrows, nodules, and urticarial plaques. Severe pruritus affects most patients unless they are immunocompromised.64 In the latter case, scabies may resemble psoriasis or a hyperkeratotic dermatosis. The infection is not life-threatening but is often debilitating and depressing. Common areas infected include the finger webs, wrists, waistline, axillary folds, genitalia, buttocks, and nipples.65 Any area of concern should be scraped and microscopically examined for mites. Early confirmation is imperative to avoid secondary infection and rapid spread in the susceptible nursing home environment.66 Treatment includes permethrin cream or rinse, which should be applied to all areas of the body for an 8- to 14-hour period. Mild burning, stinging, and rash may develop. Lindane cream, crotamiton, and sulfur were used previously but with less efficacy. Ivermectin is an alternative agent with the benefit of oral administration, but the FDA has not officially approved its use for scabetic infection.64 It is particularly helpful in cases of scabetic resistance to permethrin, although cases of ivermectin resistance have also been documented.67,68 Pruritus and inflammation may be treated with steroids and antihistamines.69 Parasitic lice are known to infest hair-bearing areas of the human body. Louse infection, or pediculosis, affects up to 12 million Americans each year. The offending human agents include Pediculosis humanus humanus, Pediculosis humanus capitis (larger body louse), and Phthirus pubis (pubic louse).70 Similar to scabies, transmission may be direct or indirect through brushes, clothing, or bedding. Higher levels of crowding increase transmission rates, as seen in some nursing homes. Pathogenesis involves deposition of eggs (nits) on hair shafts and subsequent hatching under conditions of 70% humidity and temperatures of 28° C (82° F) or higher.69 The main symptom of lice infestation is pruritus.25 Bite reactions, excoriations, lymphadenopathy, and conjunctivitis are other possible manifestations. Hair combing may be associated with a “singing” sound because of the interaction of the tines with the nits. Red bumps on the scalp that progress to crusting and oozing are noted in P. humanus capitis. Pediculosis is further complicated by the potential of co-transported infections. Diagnosis is established by visualization of the lice or nits. This often requires a good light source and use of a comb to expose the hair. The difficult to remove nits on the hair shafts appear as white specks on examination.70 Prevention is the best way to address lice infestations, such as avoiding continued contact with an infested individual. Chemical pediculicides, including permethrin, malathion, lindane, and pyrethrin, are the main treatment modalities. These treatments should be repeated every 7 to 10 days and, because of increasing resistance, must often be rotated.71 So-called bug busting with a wet comb and conditioner has limited efficacy. Dimethicone has been shown to treat pediculosis in a randomized controlled study in which 69% of patients were cured, and only 2% had irritant reactions.72 More studies are necessary for widespread recommendation of this treatment. All family members and contact persons should be included in therapy and prevention measures during patient treatment. Fungal infections are among the most prevalent integumentary concerns in older adults, and onychomycosis is a leading entity. Defined as a fungal infection involving the nail and nail plate, over 90% of onychomycosis is attributable to dermatophytes known as tinea unguium, and 10% to nondermatophytic molds, or Candida. The prevalence of onychomycosis has been estimated at almost 6.5% overall in the Canadian population.73 Studies have shown that onychomycosis increases with age, possibly because of poor circulation, diabetes, trauma, weakened immunity, poor hygiene, and inactivity.74 Some studies have shown the prevalence of onychomycosis in patients older than 60 years to be 20%.75 There are several classifications of onychomycosis, including distal-lateral subungual, superficial white, candidal, and proximal subungual. Distal-lateral subungual onychomycosis is the most common clinical type, often caused by Trichophyton rubrum invasion of the hyponychium, the white area at the distal edge of the nail plate. The nails become yellow and thick, with parakeratosis and hyperkeratosis leading to subungual thickening and onycholysis. Superficial white onychomycosis is often associated with HIV infection and appears as a chalklike white plaque on the dorsum of the nail.76 The proximal subungual type is also relatively uncommon and may present in immunocompetent or immunocompromised patients. In this case, the infection penetrates near the cuticle and migrates distally, resulting in hyperkeratosis, leukonychia, and onycholysis. T. rubrum is again the most frequent causative agent. Candidal onychomycosis is seen in patients with chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis.74 A patient history, physical examination, microscopy, and culture are all critical to diagnosis. Onychomycosis is best diagnosed by clipping the toenail very proximally and scraping the newly exposed subungual debris for laboratory evaluation. Toenails are 25 times more likely to be infected than fingernails.74 Typical presentation involves two feet and one hand (the dominant hand of a patient). Treatment options include topical and systemic medications, along with surgical approaches. A surgical trimming and débridement may be effective initially. Systemic therapy includes griseofulvin, fluconazole, itraconazole, and terbinafine.77 Multiple double-blind controlled studies have shown terbinafine to be more effective than fluconazole or itraconazole for dermatophyte infections.78–83 Systemic antifungals may have significant contraindications in patients on other medications. Topical treatments using amorolfine, ciclopirox, efinaconazole, or tavaborole have shown significant efficacy in the treatment of mild to moderate onychomycosis.84,85 Skin cancer is an increasingly important public health issue for the geriatric population. Current rates indicate that one in five people in the United States develops skin cancer at some point in their lifetime, with melanoma incidence increasing faster than any other cancer worldwide.86 The economic burden of skin cancer is substantial in the United States.86 The risk of skin cancer has been related to ultraviolet (UV) exposure, which has varying roles in basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and melanoma pathogenesis. The use of sunblock, avoidance of peak hours of sunlight, and proper clothing are simple preventive measures that can be followed by all patients, young and old. Early detection is critical in older patients because a 100% cure rate is possible.87 Actinic keratosis (AK), or solar keratosis, may be defined as a premalignant precursor of squamous cell carcinoma or an incipient cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma.88 There are about 5.2 million physician visits annually for AK in the United States, 60% by the Medicare population.89 These precancers are most common in light-skinned populations with year-round sun exposure who have not used appropriate sunscreens. Areas most affected include the forehead, scalp, ears, lower lip, forearms, and dorsal aspect of the hands.90 AK development is attributable to UV radiation–induced DNA mutation in select keratinocyte genes. With time, AKs may develop into invasive squamous cell carcinomas. They appear as small, skin-colored to yellowish-brown macules or papules, often with a dry adherent scale. They may feel rough to palpation, reminiscent of sandpaper, although they are asymptomatic in most patients.91 If an AK becomes painful, indurated, eroded, or greatly erythematous, squamous cell carcinoma transformation must be highly suspect. AKs may also proliferate and become exophytic so as to constitute a so-called cutaneous horn. This is particularly evident on the ear.92 Treatment for few and discrete AKs is best performed with cryosurgery (liquid nitrogen), which approaches almost 100% effectiveness and is convenient and economical. Topical treatment includes 5-fluorouracil, imiquimod, diclofenac, and photodynamic therapy with a light-sensitizing compound.90 Sun safety practice is helpful for prevention, such as proper coverage and limited outdoor activity between 10 AM and 4 PM.

Skin Disease and Old Age

Introduction

Epidemiology

Approach to the Patient

Selected Skin Conditions

Eczematous Disorders

Xerosis (Eczema Craquelé, Asteatotic Eczema)

Seborrheic Dermatitis

Pruritus

Vascular-Related Disease

Stasis Dermatitis

Elephantiasis Nostras Verrucosa

Cherry Angiomas

Venous Lakes

Infectious Diseases

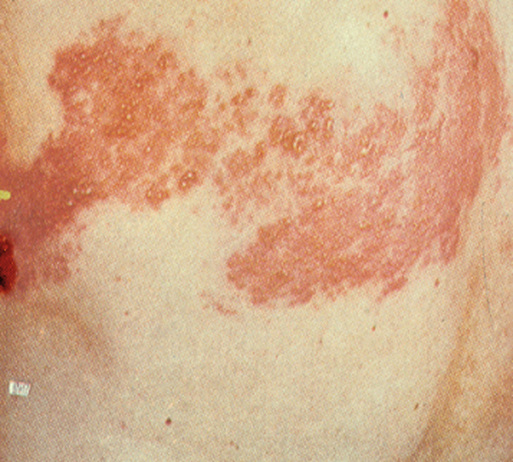

Herpes Zoster (Shingles)

Scabies

Pediculosis

Onychomycosis

Cutaneous Cancer

Actinic Keratosis

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Skin Disease and Old Age

94