and Karl Reinhard Aigner3

(1)

Department of Surgery, The University of Sydney, Mosman, NSW, Australia

(2)

The Royal Prince Alfred and Sydney Hospitals, Mosman, NSW, Australia

(3)

Department of Surgical Oncology, Medias Clinic Surgical Oncology, Burghausen, Germany

In this chapter you will learn about:

Skin cancer prevention

BCC (basal cell carcinoma)

SCC (squamous cell carcinoma)

Melanoma

Cancer of the skin is the most common cancer affecting people of European descent. It is especially common in fair-skinned people who live in sunny climates. Australians and New Zealanders have the world’s highest incidence of skin cancer, followed by the white populations of the southern regions of the United States. In fact, more than half of the white-skinned people living in these climates can expect to get one or more of the common skin cancers during their lifetime.

There are three common types of skin cancer – basal cell carcinoma (BCC), squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and melanoma. BCC is by far the most common and fortunately, the least dangerous. SCC is the next most common but is more aggressive than BCC. Melanoma is fortunately the least common of the three but is the most dangerous.

10.1 Skin Cancer Prevention

As for any health problem, the best treatment for skin cancer is prevention. BCCs and SCCs of skin can be largely prevented by avoiding too much ultraviolet irradiation from strong sunlight or artificial light in solariums. It is particularly important for fair-skinned people and especially fair and red-headed people, who live in sunny tropical or subtropical climates, to take preventative measures in their everyday lives. If exposed to strong sunlight, they are advised to wear protective clothing, broad-brimmed hats, long-sleeved shirts and long skirts or trousers, and apply sun-screening lotions on exposed skin if any time is spent in strong sunlight. They are advised to confine outdoor swimming or beach activities to early mornings or late afternoons. They are especially advised to protect the nose, lips and face in general and the backs of their forearms and hands, because of the risk of long periods of exposure. By taking such measures, the risk of developing BCCs and SCCs can be greatly reduced.

Protective measures against risk of melanoma are similar with special emphasis on the need to avoid getting sunburnt. This applies especially to children and young people who may like to remove clothing from chest, backs and limbs, thus exposing relatively white skin when days are sunny and beaches are available. The skin of young people is especially vulnerable to changes that reduce protective cells in the skin (Langerhans cells), leading to an increased risk of melanoma later in life (Fig. 10.1).

Fig. 10.1

The best preventative measure against skin cancers is to protect the skin, especially fair sensitive skin, against sunshine and other forms of ultraviolet irradiation. A large shady hat; protective skin creams, ointments or lotions; and other forms of protective clothing all give protection. The very fair-skinned girl pictured is wearing a large shady hat but would have been even better protected if she had worn a long-sleeved dress

10.2 Basal Cell Carcinoma (BCC)

A BCC is usually first noticed as a small, crusty patch or pearly grey nodule or an ulcer on the skin surface. These cancers occur most commonly in the skin that has been constantly exposed to sunshine over many years. Hence they are not common before the age of 40 and become increasingly common with increasing age. More than 70 % occur on the face because the skin of the face is most constantly exposed to the sun. The next most common sites are on the skin of the neck, the backs of the hands or forearms, lower legs, chest, shoulders and back.

BCCs are painless, usually slowly growing and may have been noticed for months or even a year or more before medical attention is sought. If neglected, they usually develop as slowly enlarging ulcers, sometimes called rodent ulcers because of the appearance that may look as though a rat had gnawed out a piece of skin. Although, fortunately, they almost never metastasise to lymph nodes or other distant tissues, they do tend to erode locally into tissues around them. Thus if neglected for a long time, they may become incurable or even fatal by causing destruction to such tissues as underlying cartilage of the nose or ear, underlying bone of the skull or large blood vessels in the neck. They can sometimes invade the orbit and paranasal sinuses and may even erode into the brain (Figs. 10.2 and 10.3).

Fig. 10.2

A typical BCC on the face

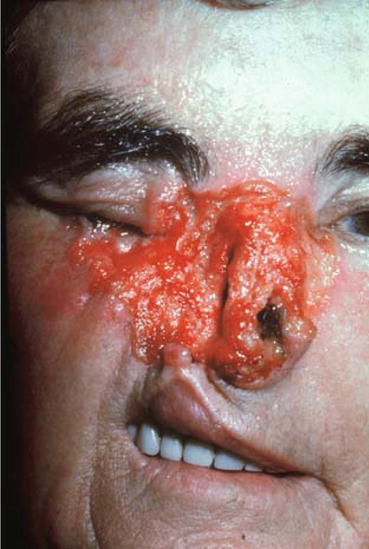

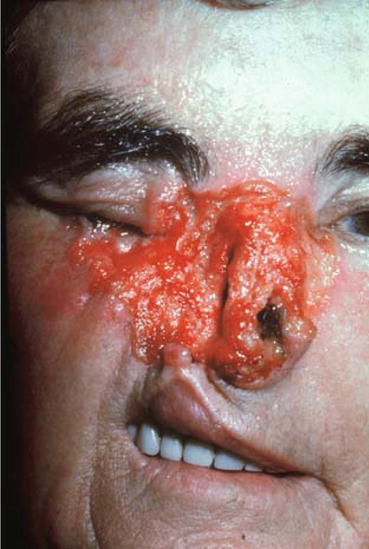

Fig. 10.3

This photograph shows a woman with a tragically neglected advanced BCC on her face. Such neglect before seeking medical attention is extremely rare. When seen, it is usually in someone who has been living in isolation. This case does demonstrate that even slowly growing BCCs can become mutilating if improperly treated or neglected for some years

10.2.1 Treatment

Very small superficial BCCs are often treated by cryotherapy, usually with a liquid nitrogen spray. If larger or extending deeper, they are better treated by simple surgical excision, usually under local anaesthesia. The tissue excised is examined by a pathologist to confirm that it was a BCC and that it was completely excised with an adequate margin of normal tissue. Radiotherapy can also be an effective method of treating BCCs but preferably after a small biopsy has been taken to confirm the diagnosis. Radiotherapy has the advantage of avoiding a surgical operation and of being a painless procedure. Radiotherapy has the disadvantage of requiring expensive specialised equipment and personnel, requiring several treatment attendances (often 20 or more) and leaving some permanent radiation damage to a small patch of skin. It also has the disadvantage that if no tissue is removed, there may be some doubt about the exact diagnosis of the lesion and whether it was completely eradicated. Nevertheless, for many small lesions, especially in elderly patients and in difficult places such as over a lacrimal duct, it may be the most appropriate form of treatment. Sometimes, small BCCs are removed by dermatologists using cauterisation or a small curette. These techniques should be left to experienced specialists because a mistake in diagnosis or incomplete removal can lead to a greater problem.

BCCs that have recurred after previous attempts at treatment or BCCs that occur close to vital structures such as a lacrimal duct or in an eyelid present special problems and require expert attention.

Large BCCs invading bone or other tissues may require extensive surgical procedures including reconstructive surgery. Very occasionally, they may even be incurable and are possibly best treated by palliative radiotherapy. (Palliative treatment will give a patient relief by reducing the tumour or lessening its symptoms without being likely to cure.) Although such advanced lesions are not common, they are disastrous when they do occur and can easily be prevented by correct treatment of BCCs in their early stages. Hence it is important for people with small lesions to seek medical help early, at which time BCCs are easily and completely curable.

10.3 Squamous Cell Carcinoma (SCC)

SCCs are also most common on the skin of the face, especially the lower part of the face and lower lip. However, they also commonly occur on the neck, the backs of the hands or forearms or skin of other frequently exposed areas such as the lower legs, back or chest.

They often develop in skin lesions called hyperkeratoses that are small, crusty or flaky thickened areas of skin, resulting from previous repeated sun damage over a long period.

An SCC is usually first noticed as a small painless, often crusty, lump growing on the surface of the skin or as an ulcer in the skin. Intra-epithelial hyperplasia (Bowen’s disease) is a very early non-penetrating SCC confined to the most superficial skin layer. It is a carcinoma “in situ” and often presents as a small red patch of the skin, possibly superficially ulcerated.

SCCs usually grow more rapidly than BCCs and, unlike BCCs, after a time, they do tend to metastasise to nearby draining lymph nodes. Later, they may spread further to more distant lymph nodes or to other distant tissues or organs such as the lung. They also grow locally and are likely to invade surrounding tissues, causing ulceration, bleeding and pain.

Fortunately, however, most SCCs of the skin have not metastasised when first diagnosed, and treatment of draining lymph nodes is usually not required. However, draining lymph nodes must be kept under close observation, and if they enlarge, they should be treated without delay – usually by surgical excision (Figs. 10.4, 10.5, 10.6 and 10.7).

Fig. 10.4

A typical SCC (squamous cell cancer) on the scalp of a bald-headed elderly man who had worked out of doors all his life as a gardener

Fig. 10.5

A cutaneous horn that is likely to develop SCC in its base

Fig. 10.6

Multiple BCCs and SCCs can develop in fair-skinned people after many years of unprotected sun exposure. This man has almost “wall to wall” cancers

Fig. 10.7

An advanced SCC of the lower lip

10.3.1 Treatment

As for all cancers, the earlier SCCs are diagnosed and treated, the less radical treatment they need and the greater the likelihood of cure.

For any lesion suspected of being an SCC, it is important for a biopsy to be taken. In the case of a small lesion, this may be best achieved by surgical excision of the whole lesion – an excision biopsy. For a large lesion, it is usually more appropriate for a small piece of tissue to be taken from its edge for microscopic examination – this is called an incision biopsy. A frozen section examination of a biopsy specimen (as described in Sect. 7.6.5) is sometimes appropriate to allow immediate complete treatment to be carried out without delay.

Very superficial SCCs (Bowen’s disease) can now be treated effectively by photodynamic therapy. The lesion is painted with a photosensitising cream and subsequently exposed to a strong light beam. Cryotherapy is also effective.

Once the diagnosis of an invasive or potentially invasive SCC in the skin is established, treatment is usually by surgical excision or sometimes by radiotherapy. Surgical excision is usually the most effective and appropriate treatment. The lesion is widely excised and examined microscopically to confirm that a margin of normal tissue surrounding the cancer has also been excised to be sure that total removal of all the primary cancer has been achieved. If draining lymph nodes are enlarged without evidence that this is due to infection, then the lymph nodes too should be removed in one block of tissue and examined histologically. Depending on the site and how much tissue has to be excised, cosmetic surgery such as a skin graft may be needed to repair the tissue and close the defect.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree