I. ACUTE REACTIONS

A. Extravasation

Extravasation is defined as the leakage or infiltration of drug into the subcutaneous tissues. Vesicant drugs that extravasate are capable of causing tissue necrosis or sloughing. Irritant drugs cause inflammation or pain at the site of extravasation. Common vesicant and irritant agents and potential antidotes are listed in Table 26.1.

1. Risk factors for peripheral extravasation include small, fragile veins; venipuncture technique; site of venipuncture; drug administration technique; presence of superior vena cava syndrome; peripheral neuropathy; limited vein selection due to lymph node dissection; and concurrent use of medications that may cause somnolence, altered mental status, excessive movements, vomiting, and coughing.

2. The incidence of extravasation for vesicant chemotherapy is recorded as 0.01% to 6.5% in the literature. Extravasation may also occur with central venous catheters. Potential causes for central venous catheter extravasation include backflow secondary to fibrin sheath or thrombosis in the central venous catheter; needle dislodgement from a venous access port; central venous catheter damage, breakage, or separation; and displacement or migration of the catheter from the vein.

3. Common signs and symptoms of extravasation are pain or burning at the intravenous (IV) site, redness, swelling, inability to obtain a blood return, and change in the quality of the infusion. Any of these complaints or observations should be considered a symptom of extravasation until proven otherwise.

4. Procedures to manage peripheral extravasation are imperative to have in place, including guidelines or orders for extravasation management of vesicant and irritant agents before administration. If an extravasation is suspected, the following actions should be taken:

1. Stop administration of the chemotherapy agent.

2. Leave the needle/catheter in place and immobilize the extremity.

3. Attempt to aspirate any residual drug in the tubing, needle, or suspected extravasation site.

4. Notify the physician.

5. Administer the appropriate antidote, as shown in Table 26.1. This may include instillation of a drug antidote or application of heat or cold to the site. Consideration for antidote order sets and verification of antidote accessibility is recommended prior to administration.

6. Provide the patient and/or caregiver with instructions, including the need to elevate the site for 48 hours and the continuation of antidote measures as appropriate.

7. Discuss the need for further intervention with the physician and photograph if indicated.

TABLE 26.1 Common Vesicant and Irritant Drugs and Potential Antidotes

Chemotherapy Agent

Pharmacologic Antidote

Nonpharmacologic Antidote

Method of Administration

Mechlorethamine HCI

Sodium thiosulfate

Apply ice for 6-12 hours following sodium thiosulfate antidote injection

Prepare one-sixth M solution: If 10% sodium thiosulfate solution, mix 4 mL with 6 mL sterile water for injection. Through existing IV line, inject 2 mL for every 1 mL extravasated. Inject SC if needle is removed.

Mitomycin Dactinomycin

No known drug antidote

Topical cooling

Apply ice pack for 15-20 minutes at least four times a day for the first 24 hours.

Doxorubicin Daunorubicin Epirubicin Idarubicin

Dexrazoxane (Totect)

Topical cooling

Dexrazoxane should be used as soon as possible and within 6 hours of the anthracycline extravasation. Administration of dexrazoxane is IV for 3 consecutive days (Day 1: 1000 mg/m2; Day 2:1000 mg/m2; Day 3:500 mg/m2) into a large vein in an area other than the extravasation area (i.e., preferably the opposite arm) over 1-2 hours. Apply cold pad with circulating ice water, ice pack, or Cryo-Gel (Cryopak, Edison, NJ) packfor 15-20 minutes at least four times a day for first 24-48 hours. Topical cooling should be removed 15 minutes before, and during, dexrazoxane administration.

Vinblastine Vincristine Vindesine Vinorelbine

Hyaluronidase (Amphadase; 150 units/1 mL; Hydase 150 units/1 mL; Vitrase: 150 units/mL)

Warm compresses

Apply heat for 15-20 minutes at least four times a day for first 24-48 hours.

Hyaluronidase is instilled as five 0.2 mL injections SC into extravasated area, using a small-gauge needle (25 g). Change needle with each injection. Hyaluronidase is stored in refrigerator.

Oxaliplatin

Case reports that use of high-dose dexamethasone (8 mg twice daily for up to 14 days) has reduced inflammation.

Warm compresses

A warm compress applied to extravasation site is preferable.

Docetaxel Paclitaxel

None

Topical cooling

Apply ice pack for 15-20 minutes at least four times a day for first 24 hours.

IV, intravenous; SC, subcutaneously.

8. Document extravasation occurrence according to institutional guidelines.

9. Continued monitoring of extravasation site at 24 hours, 1 week, 2 weeks, and additionally as guideline recommends. Secondary complications such as infection and pain may occur. Follow-up photographs at these time periods, if possible, are helpful in monitoring extent of injury and progress in healing.

5. Procedures for central extravasation are also critically important to follow, as extravasation of chemotherapy agents in the upper torso or neck area is difficult to manage and may result in extensive defects, requiring reconstructive surgery. Extreme caution should be taken by nurses administering chemotherapy by this route. Procedures followed in central extravasation are similar to peripheral extravasation. Assessment of lack of blood return, patient reports in changes of sensation, pain, burning, or swelling at the central venous catheter site or chest warrant immediate discontinuation of chemotherapy. Prompt administration of the appropriate antidote is recommended, but if the extravasation has been extensive, these actions may not prevent damage. Collaboration with the physician regarding the need for further studies to identify the cause of the extravasation will be necessary as well as decisions for future plans for venous access.

B. Infusion reactions: hypersensitivity, anaphylaxis, and cytokine-release syndrome

Specific drugs with the potential for hypersensitivity with or without an anaphylactic response should be administered under constant supervision of a competent and experienced nurse and with a physician readily available, preferably during the daytime hours. Important preassessment data to be documented include the patient’s allergy history, though this information may not predict an allergic reaction to chemotherapy. Other risk factors include previous exposure to the agent and failure to administer effective prophylactic medications. Drugs with the highest risk of immediate hypersensitivity reactions are asparaginase, murine monoclonal antibodies (e.g., ibritumomab tiuxetan), the taxanes (e.g., paclitaxel and docetaxel), and platinum compounds (e.g., cisplatin, carboplatin, and oxaliplatin). Drugs with a low to moderate risk include the anthracyclines, bleomycin, IV melphalan, etoposide, and humanized (e.g., trastuzumab) or chimeric (e.g., rituximab) monoclonal antibodies. Test doses or skin tests may be performed if there is an increased suspicion for hypersensitivity. This is most commonly done for carboplatin, bleomycin, and asparaginase. A skin testing protocol for carboplatin skin testing is shown in Table 26.2.

1. Type I hypersensitivity reactions (which may or may not be immunemediated) are the most common chemotherapy-induced type of reactions. These reactions characteristically occur within 1 hour of receiving the drug; however, with paclitaxel, the hypersensitivity reactions often occur within the first 10 minutes of the start of the infusion. Common manifestations of a grade 1 or 2 type I reaction include flushing, urticaria, fever, chills, rigors, dyspnea, and mild hypotension. Grade 3 and 4 reactions may involve bronchospasm, hypotension requiring treatment, and angioedema. Less common signs and symptoms of infusion reactions include back or abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea, incontinence, and anxiety. With appropriate premedication, the incidence of the hypersensitivity reactions has markedly decreased. Commonly used premedications include dexamethasone, diphenhydramine, and an H2-histamine antagonist such as cimetidine, ranitidine, or famotidine. Emergency equipment should be immediately accessible, including oxygen, an Ambu respiratory assist bag (Ambu, Inc., Glen Burnie, MD), and suction equipment. The following parenteral drugs should also be stocked in the treatment area: epinephrine 1:1000 or 1:10,000 solution, diphenhydramine 25 to 50 mg, methylprednisolone 125 mg, and dexamethasone 20 mg. The development of a clinical guideline for hypersensitivity reactions, with or without true anaphylaxis, may be helpful in preparing for a potential reaction, reducing delays in response time to a reaction, and standardizing the management of a reaction with standing orders. Table 26.3 provides a sample preprinted standing order for the management of hypersensitivity and anaphylactic reactions.

TABLE 26.2 Sample Carboplatin Skin Testing Protocol

All patients receiving their sixth and subsequent doses of carboplatin will have skin test dosing.

The planned carboplatin dose is diluted in 50 mL of 0.9% sodium chloride. A 0.02 mL aliquot is withdrawn and administered intradermally.

Following the intradermal injection, the injection site is examined at 5, 15, and 30 minutes.

A positive skin test is a wheal of ≥5 mm in diameter, with surrounding redness. A strongly positive skin test was one with ≥1 cm in diameter. If a patient develops a positive skin test, the physician is notified.

If the skin test is negative, the patient is then pretreated for the carboplatin with antiemetics, dexamethasone, diphenhydramine, and famotidine. Thirty minutes after the premedications are given, the carboplatin is given.

2. Cytokine-release syndrome, which is commonly referred to as infusion reaction, is a symptom complex that occurs most frequently when monoclonal antibodies are administered. This reaction is believed to be primarily related to the release of cytokines from targeted cells and other immune cells. Most

monoclonal antibodies have the potential to cause this syndrome, and the appearance may be similar to the type I hypersensitivity reaction. In contrast, however, the cytokine-release reactions may be managed by short-term cessation of the infusion, administration of histamine blockers, and restarting the infusion at a slower rate. Table 26.4 compares the differences between chemotherapy and biotherapy infusion reactions.

TABLE 26.3 Sample Standing Orders for Hypersensitivity Reactions to Chemotherapy Agents

Have the following medications available:

Diphenhydramine 50 IV

Methylprednisolone 125 mg IV or equivalent hydrocortisone

Epinephrine (1:10,000) 10-mL single-dose vial (or 1 mL of 1:1000, 1-mg vial).

If signs/symptoms of hypersensitivity occur (such as urticaria [hives], respiratory distress, bronchospasm, hypotension, angioedema, flushing, chest/back pain, anxiety), stop infusion of chemotherapy/biotherapy agent.

Maintain IV access with IV normal saline at 200 mL/hr until blood pressure stabilizes.

Administer oxygen at 2-4 L/min and measure pulse oximetry.

Administer methylprednisolone 125 mg IV push.

Administer diphenhydramine (Benadryl) 50 mg IV push.

Continuously monitor blood pressure, pulse, and oxygen saturation.

Notify physician immediately for further orders.

If symptoms do not resolve or worsen, administer epinephrine as directed by physician.

Initiate a code if airway patency is not maintained or cardiopulmonary arrest occurs.

IV, intravenous.

3. Retreatment and rechallenge of patients who have experienced paclitaxel-associated and platinum hypersensitivity reactions are supported in the literature. If a rechallenge is considered, the drug should be administered in the appropriate setting where immediate emergency situations may be handled. The decision to reinstitute the agent should be based on the clinical importance of using the drug in the particular disease setting. Patients have been successfully retreated within hours to days of the initial paclitaxel reactions at full doses; however, rechallenge with platinum compounds are generally less successful.

a. Reinstitution of paclitaxel. Patient management after experiencing a hypersensitivity reaction includes immediate discontinuation of the paclitaxel infusion at the onset of symptoms and rapid administration of additional diphenhydramine and methylprednisolone. Following stabilization of the patient and waiting approximately 30 minutes, the paclitaxel infusion is reinitiated, with initial infusion rates at 10% to 25% of the total infusion rate. If tolerated, the rate can be gradually increased over the next several hours. Nursing care

would also include vital signs every 5 minutes or continuous observation for the first 15 minutes, then every 15 minutes through the first hour, then hourly until completed. An alternative is to pretreat the patient for 24 hours with dexamethasone 10 mg X 3 orally and to restart the infusion at the rate indicated above on the second day.

TABLE 26.4 Infusion Reactions: The Comparison of Chemotherapy and Biotherapy Agents

Characteristic

Chemotherapy

Biotherapy

Reaction type

Type I hypersensitivity

Cytokine release

Timing of reaction

Platinum: after multiple cycles

Most MoAbs: first infusion

Taxanes: first or second infusion

Rituximab: any infusion

Prevention

Premedication

Premedication

Management/Rechallenge

Grade 1 or 2: premedication—reinitiate infusion at slower rate

Dependent on grade Interruption

Premedication

Grade 3 or 4: not likely to rechallenge

Reinitiate at slower rate

Grading

1: Transient flushing/rash/fever >38°C

2: Rash; flushing; urticaria, dyspnea, fever >38°C

3: Symptomatic bronchospasm, with/without urticaria; parenteral medications indicated; allergy-related angioedema; hypotension

4: Anaphylaxis

5: Death

1: Mild reaction: No infusion interruption

2: Infusion interruption; responds promptly to symptomatic treatment (drugs, fluids); prophylatic medications indicated for ≤24 hours

3: Prolonged/recurrences of symptoms after initial improvement; hospitalization indicated

4: Life-threatening; pressors or ventilator needed

5: Death

MoAb, monoclonal antibody.

b. Desensitization approaches. Rechallenge after a severe hypersensitivity reaction of the second episode of hypersensitivity reaction to paclitaxel and platinum agents (cisplatin, carboplatin, oxaliplatin) are documented in the literature; however, planning for the desensitization is necessary. Regimens including dexamethasone 20 mg orally at 36 and 12 hours before chemotherapy and the morning of chemotherapy have been studied. A full 30 minutes before the chemotherapy, other IV premedications such as dexamethasone 20 mg, diphenhydramine 50 mg, and a H2-histamine antagonist are given. For paclitaxel, the desensitization procedure continues with administration of a test dose of 2 mg in 100 mL of normal saline over 30 minutes. If there is no reaction, 10 mg in 100 mL of normal saline is given over 30 minutes, followed by the remaining full dose

in 500 mL of normal saline over 3 hours if there is still no reaction. If a reaction is experienced, the usual diphenhydramine and methylprednisolone medications are given.

II. NAUSEA AND VOMITING

Patients who are about to begin chemotherapy are often concerned and apprehensive about nausea and vomiting. Nausea and vomiting can be distressing enough to the patient to cause extreme physiologic and psychological discomfort, culminating in withdrawal from therapy. With the advent of more effective antiemetic regimens in the last 20 years, many improvements in the prevention and control of nausea and vomiting have led to a better quality of life for patients receiving chemotherapy. The goal of therapy is to prevent the three phases of nausea and vomiting: that which occurs before the treatment is administered (anticipatory), that which follows within the first 24 hours after the treatment (acute), and that which occurs more than 24 hours after the treatment (delayed). It is also important to assess nausea and vomiting separately because they are different events and may have different causes. Factors related to the chemotherapy that can affect the likelihood and severity of symptoms include the specific agents used, the doses of the drugs, and the schedule and route of administration. Other patient characteristics that may affect emesis include history of poor emetic control, history of alcoholism, age, gender, anxiety level, and history of motion sickness.

A. Emetic potential of the drug

To plan an effective approach to control nausea and vomiting, the chemotherapeutic agents are grouped according to their emetic potential (Table 26.5). This type of categorization is helpful in making decisions regarding possible antiemetics to be used and how aggressive the antiemetic regimen should be for patients receiving chemotherapy for the first time or in subsequent treatments. It is important to select appropriate antiemetics from the various antiemetic classes and to not undertreat the patient for nausea and vomiting in the initial chemotherapy cycle. Failure to control nausea and/or vomiting may result in a conditioned response and subsequent anticipatory nausea and vomiting.

B. Antiemetic drugs

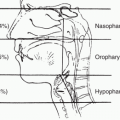

Agents that have been effective in preventing and treating nausea and vomiting (Table 26.6) come from various pharmacologic classes. They work by different mechanisms that may relate to the pathophysiologic processes causing nausea and vomiting. Within the last 20 years, it was discovered that agents that block predominately the serotonin 5-hydroxytryptamine subtype 3 (5-HT3) receptors, rather than the dopamine receptors, have greater efficacy in the prevention of nausea and vomiting. More recent research indicates that the tachykinins, including a peptide called substance P, play an important role in emesis. Substance P binds to the neurokinin

type 1 (NK-1) receptor. Thus, the NK-1-receptor antagonists are now validated in their role in inhibiting nausea and vomiting with moderately and highly emetogenic chemotherapy. NK-1-receptor antagonists are thought to improve acute nausea and vomiting associated with chemotherapy when combined with standard regimens (i.e., dexamethasone and 5-HT3

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Side Effects of Chemotherapy and Molecular Targeted Therapy

Side Effects of Chemotherapy and Molecular Targeted Therapy

Janelle M. Tipton

The supportive care of patients receiving cancer chemotherapy and molecular targeted therapy has improved considerably over the last two decades. Contributions to the substantial improvements include better understanding of the pathophysiology of specific side effects, increased knowledge and attention to risk factors, and availability of newer agents for prevention and management of side effects. The side effects of systemic cancer treatment may be acute, self-limited, and mild, or can be chronic, permanent, and potentially life threatening in nature. Although much progress has been made, the management of side effects continues to be of utmost importance for the tolerability of therapy and effect on overall quality of life. In addition, inadequately controlled side effects may lead to increased use of healthcare resources and costs, and may occasionally impact adherence to therapy. The implementation of evidence-based interventions has received recent emphasis and is critical in making appropriate clinical decisions for patient safety and the management of side effects.