Sentinel lymph node (SLN) biopsy is now a standard component of the treatment of many melanomas, and its use is accepted as routine.1,2 So routine, in fact, that the revolutionary nature of its beginning is little remembered. This is appropriate as the technique and the clinical data supporting its use are now both broad and deep. However, even with our familiarity with the procedure, it is important to remember that the technique requires skill and coordination of multiple disciplines and that appropriate selection of candidates for SLN biopsy is necessary. The impact of SLN biopsy has now spread from melanoma to breast cancer, and may become more common in other solid tumors. The benefits it has produced for melanoma patients around the world including more accurate staging and less morbid treatment of regional lymph nodes are remarkable and will ensure that SLN biopsy will continue to be a vital component of melanoma treatment into the future.

The history of SLN biopsy is, in some respects, quite old. Indeed, since the apparent orderly progression of cancer from primary tumor to lymph nodes and then subsequently to distant sites has been observed for centuries, the concept of determining a reliable means of mapping that progression is not new. For example, Rudolph Virchow, father of modern pathology, noted drainage of carbon pigment from a skin tattoo to specific lymph nodes.3 Leonard Brathwaite, a British surgeon, examined lymphatic drainage from the omentum using blue dye and described a “gland sentinel” at the root of the small bowel mesentery that received the drainage.4

Gould et al5 described a “sentinel” node located close to the junction of the facial and jugular veins that was the drainage point for tumors of the parotid gland. Cabanas6 described a “sentinel” node located adjacent to the superficial epigastric vein at the level of the junction of the femoral head and ascending pubic ramus that received drainage from tumors of the penis. He postulated that this node would provide information representative of the tumor status of the entire nodal basin.

However, all of these concepts were founded on the assumption that there was a consistent, anatomically determined lymph node that would act as sentinel. None proved to be a reliable indicator of nodal staging that could be applied more generally. What was required was a procedure that took into account functional information in determining the drainage pattern of a primary tumor. This accomplishment was not achieved until the 1980s, and was arrived via another route of investigation.

In melanoma, the subject of treatment of clinically negative regional lymph nodes has been controversial at least since “anticipatory gland excision” was proposed by Herbert Snow7 at the end of the 19th century. Over most of the 20th century, there were proponents and opponents of elective regional nodal dissection, eventually leading to a series of randomized clinical trials.8–10 However, for patients with primary tumors located in regions with ambiguous lymphatic drainage, the appropriate basin for elective dissection was frequently unclear. In 1977, Holmes et al11 recommended a rational approach to determine what basin(s) was(were) at risk. This approach used lymphoscintigraphy, initially with radioactive colloidal gold, to determine which nodal basin received drainage from the primary tumor site and selectively dissect that basin. In their examination of this approach, no nodal disease was encountered in basins that also did not show drainage by the exam.

As radiotracers and imaging equipment improved, it became increasingly apparent that drainage was not to an entire basin, but rather to a specific lymph node or small number of nodes. Holmes et al11 hypothesized that identification of that particular node would enable determination of the pathologic status of the nodal basin, without the need for a complete dissection. He proposed mapping of the lymphatic drainage using vital blue dye injected at the primary tumor site. Studies in a feline model confirmed that this process was technically feasible.12 Initially in patients, the entire path of the lymphatic channels was opened and followed, and all patients also underwent complete node dissection to determine if the mapping had been accurate.13

This initial patient experience was reported at the Society of Surgical Oncology Symposium in 1990 and demonstrated that, indeed, the status of the basin was accurately represented by the SLN.14 Among 237 lymphadenectomies, only 2 (0.8%) had metastases in basins in which the identified SLN was negative. It was therefore possible to determine in which patients a regional nodal dissection was indicated without having to subject everyone to the morbidity of that procedure. This report was initially met with considerable skepticism. Publication of the result was not achieved for nearly 2 years.13 History has now confirmed the reliability of SLN biopsy as the gold standard for regional disease staging in melanoma, and that initial publication is now the most highly cited surgical oncology paper of all time.15

As discussed below, the value of SLN biopsy for patients with intermediate-thickness melanomas in determining prognosis, attaining regional control, and possibly improving long-term survival is sufficient to merit offering the procedure to operative candidates. This recommendation is now standard in the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines as well as guidelines endorsed by the American Society of Clinical Oncology and Society of Surgical Oncology.1,2 Certainly all patients in this group should be informed about the procedure and allowed to consider it as a standard option.

For thick melanomas, the risk of systemic metastases is relatively high, which may diminish the importance of regional nodal staging. This group was not considered for elective lymphadenectomy for this reason, and indeed, in the World Health Organization study of elective node dissection, patients with thicker primary melanomas did not have any indication of benefit from the procedure.16 However, since SLN biopsy can be performed with relatively little morbidity, the procedure has been evaluated in these patients to determine its prognostic value.

Several series have been published showing a strong relationship of the status of the SLN and survival for patients with melanomas >3.5 or 4 mm in thickness. Gershenwald et al17 examined 131 patients with thick melanoma and found the SLN status to be a strong independent prognostic indicator with 3-year overall survivals of 89.8% and 66.4% for SLN negative and positive, respectively. Together with ulceration status, SLN biopsy was able to segregate patients in to higher or lower risk categories. This information may affect a patient’s evaluation of potential adjuvant therapies, clinical trials, and follow-up schedules. The Italian Intergroup and the Sunbelt Melanoma Trial Groups have also published large experiences of these patients, both showing significant prognostic value of SLN status.18,19

Most thin melanomas have very low risk of nodal metastases, but there is a subgroup that has nodal disease even with thin lesions. Given the large number of thin melanomas, a relatively small percentage with nodal metastases results in a substantial absolute number of positive lymph node patients. The challenge, then, is to identify appropriate patients within the thin population for SLN biopsy since the vast majority of these patients have risks too low to justify the procedure.

Two approaches have been taken to study this question. The first is to examine patients with thin melanoma who have undergone SLN biopsy and determine which factors were associated with nodal involvement.18,20–22 This approach is intuitive but has inherent limitations. First, patients undergoing SLN biopsy have already undergone selection and may not be representative of the overall thin melanoma population. Second, false-negative biopsies would weaken the analysis. In the series that have been reported, there is little agreement on appropriate selection criteria for biopsy. Commonly, measures of thickness or invasion have been used with tumors thicker than 0.75 mm or Clark level IV felt to be at higher risk. Other features such as ulceration or a high mitotic rate are rare in thin melanoma and may not be of much practical help. Two other features that may play a role are the age of the patient, which appears to be inversely related to the risk of nodal involvement, and regression. Regression was classically considered to be an adverse prognostic indicator. It was hypothesized that regressed tumors were the remnant thicker, higher risk melanomas and were attended by a worse prognosis than nonregressed tumors of similar final thickness. However, more recent series suggest that thin melanomas with regression are less aggressive and less likely to be associated with nodal disease, and this now forms the bulk of the available data. The source of this change in the prognostic meaning of regression is not clear, but it is possible that the nature of pathologic evaluation would have changed over the years, but no objective data provide a clear explanation.

An alternate study design utilizes the population of patients with thin melanoma who did not undergo SLN mapping and determines nodal involvement by a clinical nodal recurrence.23,24 While this approach requires extensive follow-up, it avoids the issue of operative selection and false-negative tests. Several such studies have been performed and also suggest a relationship of nodal involvement to thickness (by Breslow or Clark) to nodal recurrence, even in this thin population. Several studies also suggest gender as a factor with males having greater risk.

The inconsistency of these studies has led to a lack of clarity from the available data regarding precise selection features. The NCCN guidelines leave room for interpretation by the patient and surgeon.1 They suggest that for melanoma <0.75 mm without adverse features, SLN biopsy should rarely be considered except in cases with uncertain primary tumor staging. In tumors >0.75 mm in thickness with no adverse features, SLN biopsy should be discussed and considered. For tumors >0.75 mm in thickness with adverse features, SLN biopsy should be discussed and offered.

As noted above, the SLN technique initially used only blue dye intraoperatively, with a preoperative lymphoscintigram used only to determine which nodal basin was at risk.13 In addition, the entire course of the lymph channel was dissected in continuity. The advent of improved imaging and of hand-held, intraoperative gamma probes enabled more accurate and less involved procedures. The current standard approach uses a combination of vital blue dye and radiotracer. The dyes in routine use now include lymphazurin and methylene blue. The two dyes appear to have similar utility. Some favor methylene blue due to the risk of allergic reaction with lymphazurin. However, the rate of such a reaction in melanoma patients appears quite low (relative to studies in breast cancer). In two large prospective clinical trials, the rate of allergic reaction to blue dye was <0.1% and 0.17%.25,26 Methylene blue has also been associated with skin necrosis, and would be relatively contraindicated if the injection site is not to be excised (e.g., if a wide excision has previously been performed).27 Surgeon preference also plays a role in selecting dyes.

The current available radiotracers vary based on which part of the world the procedure is being performed in. In the United States, the most commonly used tracer has been technetium sulfur colloid (either filtered or unfiltered). Other options are technetium-labeled albumen, which is also a standard agent in Europe. In Australia, technetium-labeled antimony sulfide colloid is the tracer of choice. A new agent, tilmanocept, has recently completed phase III clinical trials and has received regulatory approval. This small molecule is also tagged to technetium but is localized to the sentinel node by a specific targeting mechanism due to the presence of a carbohydrate antigen. The molecule binds to mannose receptors on antigen presenting cells in lymph nodes and are then taken up and retained by those cells. This has been evaluated in two single-arm phase III trials and found to be a reliable mapping agent.

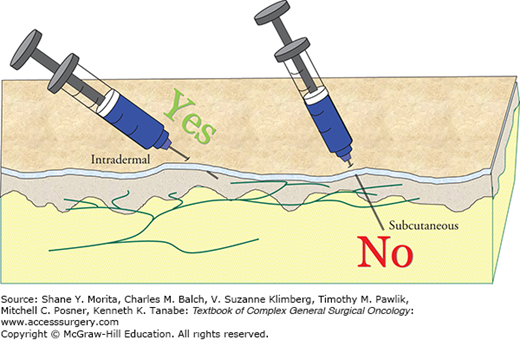

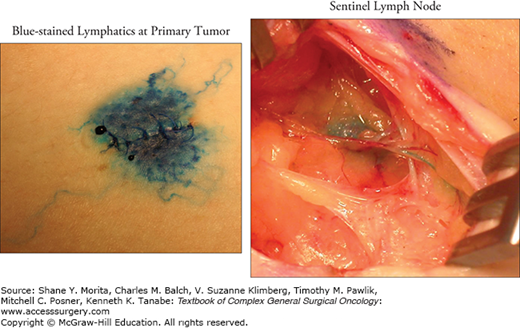

Usually lymphoscintigrams are performed on the day of the biopsy, although it is also possible to have them done the afternoon prior to the procedure. The blue dye is injected at the time of the procedure, generally just before the area is prepped. Care should be taken during the injection to infiltrate the dermis rather than injecting into the subcutaneous tissue (Fig. 14-1). This is due to the rich infiltration of lymphatic channels into the dermis, and their relative absence from the subcutis (Fig. 14-2). Gentle massage can be used to increase the lymph flow, but is generally unnecessary if the injection is done correctly.

Often the nuclear medicine physician will mark the skin overlying the sentinel node site to facilitate its identification at surgery. However, it is quite important for the surgeon to verify this location at the time of surgery. This is because changes in patient position and possibly additional drainage time may alter the findings at the time of lymphoscintigram. For example, lymphatic lakes, which can appear similar to lymph nodes on a scan, will clear of radioactivity with more time.

During the biopsy procedure, a great deal of progress to the node location can be accomplished with blunt dissection, limiting transection of lymphatic channels that are not connected to the SLN and potentially avoiding trauma to local nerves. When the SLN is found, it is very important to treat it with care. Lymph nodes are often delicate structures and grabbing or pulling on the capsule of the node will often lead to tearing, which will be associated not only with minor bleeding in the operative field but also with potential adverse implications to the accuracy and reliability of the pathologic evaluation of the node, since small metastases are frequently located in the subcapsular area (Fig. 14-3). A better technical approach uses pushing or lifting motions from beside or beneath the node for manipulation. This will decrease trauma to the nodal tissue and facilitate pathologic evaluation.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree