The ability to recirculate from blood to tissues and back through the lymphoid system is unique to lymphocytes and, coupled with their long lifespan and specificity for individual antigens, equips them for their central role in adaptive immune responses.

The thorough mixing of lymphocytes, particularly in the spleen and lymph nodes, ensures the maximum contact of antigen-presenting cells that have newly encountered antigen, with T and B lymphocytes potentially able to respond, which would otherwise be a very rare event. The body-wide dissemination of expanded T and B populations in readiness for a second encounter with the same antigen ensures that ‘memory’ is available at all sites.

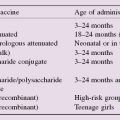

Different types of lymphocyte ‘home’ to different regions in the lymphoid organs (T and B areas in the figure; B areas are shaded). This ‘lymphocyte traffic’ is regulated by a combination of chemotactic factors released from particular sites (mostly members of the chemokine family; see Fig. 7) and direct contact via adhesion receptors (sometimes known as ‘addressins’ because they direct lymphocytes to particular sites in the body) between lymphocytes and the extracellular matrix or other cells such as the inner surface of the vascular endothelium or the dendritic antigen-presenting cells (not shown here, but see Fig. 8). The introduction of a new form of fluorescent microscopy, known as two-photon microscopy, has allowed the visualization of lymphocyte movement within living lymphoid tissue.

In general, lymph nodes respond to antigens introduced into the tissues they drain, and the spleen responds to antigens in the blood. The gut, lungs, breast and external mucous surfaces also have their own less specialized lymphoid areas that to some extent behave as a separate circuit for recirculation purposes and are often known as the mucosa-associated lymphoid tissues (MALT). These can be further subdivided into gut-associated (GALT), bronchial-associated (BALT) and skin-associated (SALT) lymphoid tissue. In each case, the objective seems to be to provide a local lymphoid system specialized for the antigens most likely to be encountered there.

Lymph Node

Lymph nodes (or ‘glands’) constitute the main bulk of the organized lymphoid tissue. They are strategically placed so that lymph from most parts of the body drains through a series of nodes before reaching the thoracic duct (TD), which empties into the left subclavian vein to allow the lymphocytes to recirculate again via the blood.

AL, EL

Afferent and efferent lymphatics, through which lymph passes from the tissues to first peripheral and then central lymph nodes. The cells found in afferent and efferent lymph are quite different. Naïve T cells enter lymph nodes from blood, but then leave via the efferent lymphatics, before eventually rejoining the blood. Memory or effector T cells enter tissues at sites of infection, and then travel back to lymph nodes via the afferent lymphatics. Afferent lymph also carries antigen and dendritic cells (known as veiled cells while in lymph) as they migrate from tissues such as the skin to the T-cell areas of the lymph node.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree