BACKGROUND

The questions posed in the case history have been addressed in several studies. Not all studies have reached the same conclusions about the same issue. Some have questioned the need for any screening for GDM. Their argument rests on the paucity of data demonstrating that the treatment of GDM causes a positive change in maternal, perinatal, or neonatal outcomes.1 However, two randomized controlled trials have demonstrated a reduction in large for gestational age neonates and in birth trauma with treatment for GDM.2,3

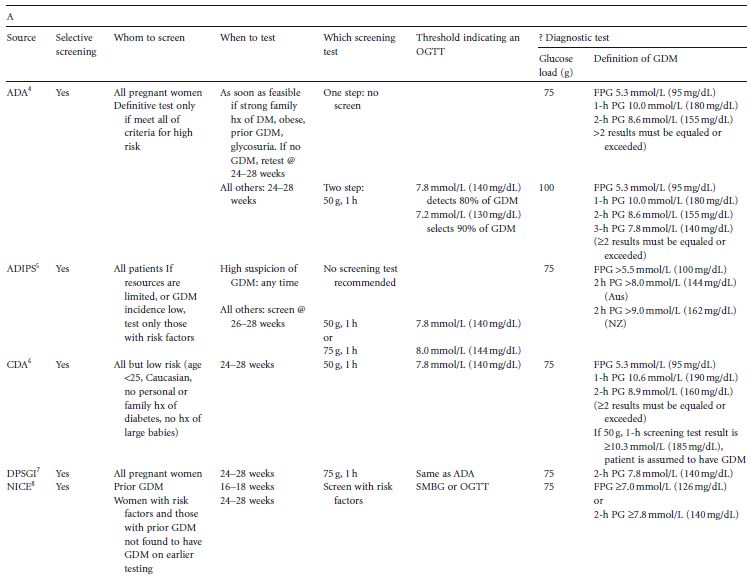

Conventionally, a screening test is employed to determine whether a definitive diagnostic test (OGTT, in the context of GDM) is indicated. Over the years much controversy and confusion has existed over how and when to screen for GDM. A variety of screening tests and testing protocols have been recommended (Table 5.1 A).4–10 This chapter will review the current issues surrounding screening for GDM. It will address concerns regarding the method, timing, and frequency of testing for hyperglycemia in pregnancy, threshold values used to indicate an OGTT, and whether a screening test need be utilized at all in deciding whether or not to perform an OGTT during pregnancy.

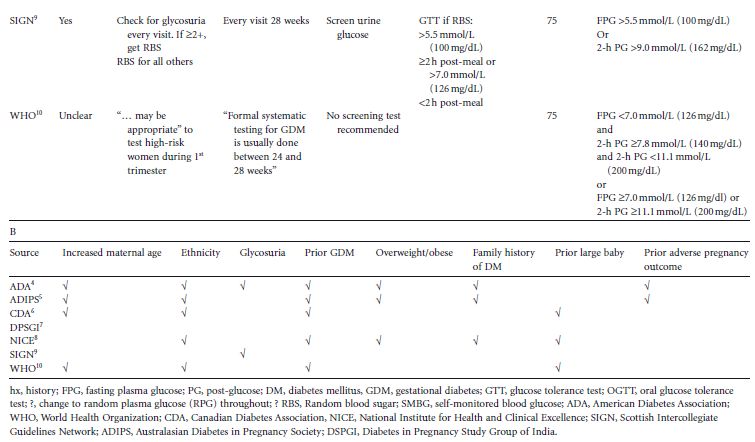

Table 5.1 (A) Details of protocols for screening for gestational diabetes. (B) Factors specified by different groups to define high risk.

DEFINITIONS

The terms “screening” and “diagnosis” are often used interchangeably. In the context of detecting glucose intolerance in pregnancy, a screening test is one that identifies women at greater or lower risk for diabetes, depending upon whether the test results fall above or below a threshold glucose concentration, respectively. It does not, however, identify those who do or do not have the disease. Most testing algorithms require that women exceeding a selected threshold concentration on the screening test proceed to a definitive test (OGTT). Thus, a screening test for diabetes identifies a subgroup of the population which is at greater risk for the disease. Within this subgroup, a relatively small minority will be found to have diabetes. Conversely, within the subgroup defi ned as being at lesser risk, there will be another minority who, if tested, would also be found to have diabetes. In contrast to a screening test, an OGTT (the diagnostic test) will usually provide a definitive answer as to the presence or absence of diabetes.

SCREENING

Universal versus selective s creening

There is no consensus among international bodies as to whether screening for GDM is justified, and if so, whether universal or selective screening is most appropriate (Table 1A).4–10 The argument for selective screening is primarily one of cost savings. However, to be both cost-effective and clinically useful, a screening test must be both sensitive and specific. As will be discussed, few data exist for determining both of these important characteristics for any screening test for GDM. The ideal would be to develop a definitive test which requires little preparation and takes little time to perform, without requiring the prior interposition of a screening test, and which could be applied to the entire obstetric population. This universal approach to testing for GDM has been recommended by some.

Screening by clinical characteristics

In all likelihood, because of the time and expense of screening, criteria based on patients’ demographics and medical histories have been proposed to select those patients who should receive definitive testing for GDM. This screening method is attractive, because it utilizes readily ascertainable information. Included among the risk factors used to select women for definitive testing are increased maternal age, membership of an ethnic group known or suspected to have a greater prevalence of GDM and/or of non-gestational diabetes, random glycosuria, GDM in a prior pregnancy, overweight and obesity, a family history of diabetes, and a prior large baby (Table 5.1 B). Unfortunately, each of these factors is not uniformly, and is sometimes vaguely, defined. Furthermore, to determine the proportion of women with one or more of these risk factors who have GDM (positive predictive value), glucose tolerance testing has to be performed on only those women who have one or more risk factors. To determine the proportion of all women with GDM who have one or more risk factors (sensitivity), and those who have GDM but no risk factors (false negative rate), definitive (glucose tolerance) testing would have to be done on all pregnant women. Few studies with this design have been reported. Perhaps as a consequence of the lack of pertinent data, the selection of risk factors currently recommended to determine candidacy for glucose tolerance testing is not uniform (Table 5.1 B).4–10

Screening tests using glucose loads

Screening for hyperglycemia during pregnancy using a 50-g oral glucose load followed by a blood sample for glucose concentration 1 hour later is likely the most commonly used method to determine whether or not a patient merits an OGTT. While it offers the advantages of simplicity and ease of interpretation, the test has significant drawbacks, which have become evident over the years.

History

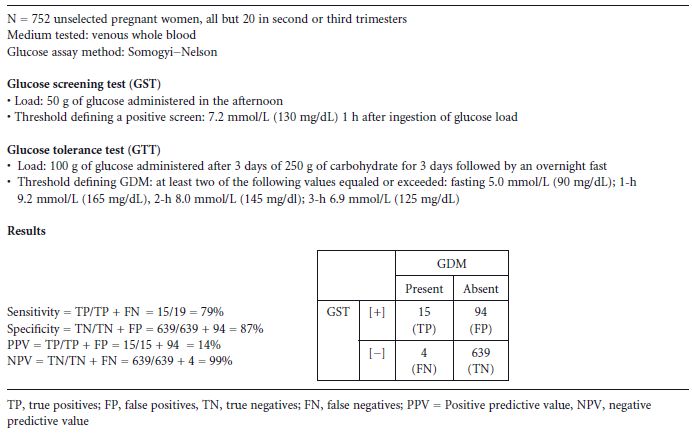

To determine the proportion of the patient sample which will be correctly or incorrectly identified as being at risk for a given disease, both the screening and the definitive test must be administered to all subjects. In 1973, O’Sullivan et al published a study in which both a 50–g, 1-hour GST and a 100-g OGTT were administered to 752 unselected women, most of whom were in the second and third trimester. The authors determined that a threshold value of 7.2 mmol/L (130 mg/dL) detected 79% of women who subsequently had a positive OGTT, while 87% of those without GDM would not have been (unnecessarily) tested with the OGTT11 Table 5.2. Although multiple studies have since appeared employing a variety of screening tests for GDM, few have administered both screening and definitive tests to all subjects. This is an important omission, as it leaves unanswered the question of what proportion of the patient sample that has GDM will be detected or missed by testing only those above the threshold value selected for a particular screening test.

Table 5.2 Methodology and results of a study of the 50-g, 1-hour glucose screening test for gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM).11

Screening test thresholds

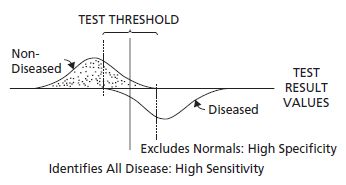

It is unclear from the O’ Sullivan data why a threshold of 7.2mmol/L (130mg/dL) was chosen for the 50-g, 1-hour screening test. Selection of a lower screening threshold results in detection of a greater proportion of women within the population who have GDM (i.e. increased sensitivity of the screening test), but at the cost of selecting for definitive testing more women without GDM (i.e. reduced specificity) (Fig. 5.1). In the O’ Sullivan study, the selection of the 7.2 mmol/L (130 mg/dL) threshold provided a reasonable sensitivity of 79% and a specificity of 87%, but it should be noted that there were only 19 subjects who had GDM among the 752 studied. It is likely that a few more diabetic women on either side of the 7.2 mmol/L (130 mg/dL) threshold would have substantially altered the performance of the screening test Table 5.2.

Fig. 5.1 Hypothetical distribution of results of a diagnostic test (curves) and a screening test for the disease (horizontal line). The lower end of the distribution of values is on the left, and the upper end on the right. The influence of raising or lowering the screening test threshold may be envisioned by moving the vertical line to the right or left. (Reproduced from Carpenter and Coustan,13 with permission from Elsevier.)

One of the difficulties in applying the O’ Sullivan data is that over the years changes have occurred in glucose assay methods and the medium assayed. First, the less specific (Somogyi–Nelson) method, which assays for all reducing substances, has been replaced by enzyme-based assays specific for glucose (e.g. glucose oxidase, hexokinase, glucose dehydrogenase). Second, the glucose assay is now performed on plasma rather than on whole blood. The concentration of glucose in plasma is greater than that in red blood cells. Thus, based on current methodology (enzyme assay of plasma) alone, to maintain equivalence with the results obtained by O’ Sullivan the GST threshold would have to be numerically lowered if only the difference in assay methods is considered, but raised if only the difference in concentration of glucose in plasma compared with that in whole blood is considered. The Carpenter–Coustan diagnostic threshold values defining GDM12 were empirically derived by adding 14% to the O’ Sullivan criteria11 to adjust for the differences between whole blood and plasma, and subtracting 0.28 mmol/L (5 mg/dL) to adjust for the differences in assay methods. A subsequent study developed a conversion equation by comparing results using the same patients’ blood specimens of glucose concentrations in whole blood assayed with the Somogyi–Nelson method with those obtained by assaying their plasma with glucose oxidase. The empirically-derived Carpenter–Coustan criteria were all found to be within the 95% confidence intervals of the glucose thresholds derived with this formula.13

The effect of raising or lowering the 50-g, 1-hour GST threshold on sensitivity and specificity was evaluated in a study of 704 unselected pregnant women between 24 and 28 weeks of gestation. All subjects were given a 50-g GST in the fasting state followed by a 100-g, 3-hour OGTT within 1 week of the screening test. Using receiver–operator characteristic curves, the authors found that the optimal balance of sensitivity and specificity (respectively 91% and 73%) using Carpenter–Coustan diagnostic criteria13 was achieved at a screening test threshold of 7.8mmol/L (141mg/dL).14

The incidence of GDM among women who have had an OGTT following a 1-hour screening test result greater than or equal to 11.1 mmol/L (200 mg/dL) is reported to vary from 10% to 47%.15–19 Thus, it seems prudent to perform an OGTT following an elevated GST result of any magnitude.

Timing of the test

Standard screening procedures make no adjustments for gestational age at testing. Some stipulate the time of day that the test is to be administered or the time of testing relative to the last meal.5 Others state that the test should be given without regard to either.4,6 The potential influence of gestational age was examined in a study using cross-sectional data in which women were tested serially at 20, 28, and 34 weeks. Among those whose previous test result was less than 7.8 mmol/L (140 mg/dL), the mean increment in post-challenge plasma glucose was 0.06mmol/L/week (1.1mg/dL/week).20 A similar increment was noted in a further study in which all women who tested negative for GDM in the first trimester had a repeat screening test in the third trimester. In the latter study, of those patients whose first trimester result was less than or equal to 6.1 mmol/L (110 mg/dL) (56% of the 124 subjects in the study), only 10% equaled or exceeded the 7.5mmol/L (135mg/dL) threshold upon repeat testing in the third trimester, and none of the latter was found to have GDM on testing with the OGTT. The authors concluded that it is probably unnecessary to perform further testing for GDM if the first trimester screening test is less than or equal to 6.1 mmol/L (110mg/dL).21

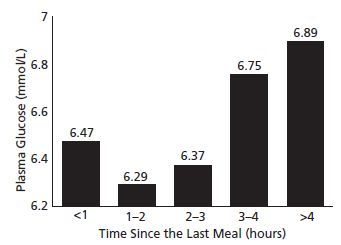

Two studies examined the influence of timing of the last meal prior to the GST, and demonstrated that the longer the fast prior to the glucose load, the higher the maternal glucose concentration 1 hour after loading.22,23 One study noted a J-shaped relationship between duration of the fast prior to the test and the test result (Fig. 5.2). In the other report, screening test results of women with GDM were significantly lower if the women had been fed 1 hour prior to testing compared with those tested directly following an overnight fast. In the latter report no significant differences in post-glucose load test results were found between non-diabetic women who had or had not been fed prior to glucose loading.23 Thus, while time of the last meal prior to administration of the 50-g glucose load does affect the GST result, the finding of improved glucose disposal following successive glucose loads (Staub–Traugott effect24,25) in pregnant women remains unexplained.

The time of day that the glucose load is administered may also affect the test results. Data comparing tests results when the glucose load was given in the morning with those when the GST was administered in the afternoon to demographically similar groups26 and to the same subjects27 demonstrated significantly elevated post-glucose challenge maternal glucose concentrations when tested in the afternoon.

Fig. 5.2 Relationship between 50-g post-load mean maternal plasma glucose and time elapsed in hours since last meal. (Reproduced from Sermer et al,22 with permission from Elsevier.)