© Springer International Publishing Switzerland 2017

Jan B. Vermorken, Volker Budach, C. René Leemans, Jean-Pascal Machiels, Piero Nicolai and Brian O’Sullivan (eds.)Critical Issues in Head and Neck Oncology10.1007/978-3-319-42909-0_1212. Salvage Surgery of Head and Neck Cancer

(1)

VU University Medical Center, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

The role of the modern surgeon is evolving, with more emphasis on salvage surgery than before. Besides, surgery must treat complications and sequelae of chemotherapy and radiotherapy, such as edema, strictures, and radionecrosis. Surgery may also be an option for certain selected cases of distant metastases, but this will not be described herein.

Treatment guidelines, including the NCCN Guidelines for recurrent or persistent disease after prior radiation therapy advise surgery as first line treatment in tumor is resectable [1]. Depending on adverse features of histopathology, adjuvant (chemo) re-irradiation may in very selected case be indicated. Salvage surgery for (chemo) radiation failure is thus increasingly employed for cancers of the oropharynx, larynx, and hypopharynx and offers the best chance of survival for the patient.

However, not all recurrent disease is operable. The surgeon must ensure meticulous preoperative assessment and decision-making before embarking on this rescue modality. It is of great importance that the description of the original tumor is taken into account, as well as the extent at the time of recurrence. As a rule of thumb, an originally unresectable case will remain unresectable, even if the recurrence seems resectable. Also the tumor extent on imaging is vital and a careful discussion with the radiologist is mandatory. Limitations of surgery include resection of the common or internal carotid artery and prevertebral fascia. Involvement of these structures indicates a biologically highly aggressive tumor and although technically feasible, resection of these structures may bring more harm than benefit to the patient. It is here that the surgeon’s experienced judgment becomes vital to balance these two extremes. Total glossectomy for salvage is feasible as a life-altering procedure. These patients may still have useful communication and a soft oral intake without aspiration. A laryngectomy in conjunction with a total glossectomy for recurrences at the interphase of these two major structures is also technically possible, but this may be a procedure that is just a bridge too far in view of the expected therapeutic ratio. Esophagectomy in order to achieve clear margins is technically possible, albeit (for head and neck cancer recurrence after chemoradiation) with only moderate help on the expense of severe complications and high morbidity. In general salvage surgery is only feasible in a minority (20–40 %) of patients, making initial multidisciplinary decision-making for the primary treatment even more important; the expression “we will start with non-surgical treatment, and in case of recurrence we can always operate” is not true.

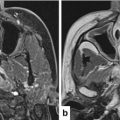

Also, early detection or recurrence and subsequent salvage yields improved control and survival and therefore reliable diagnostics are essential. MRI and CT lack specificity due to edema, delayed volume reduction, and artifacts by dental filling. The negative predictive value of FDG-PET-CT at 3 months is in general very reliable; at earlier points in time, there is a high incidence of equivocal and inaccurate interpretation both at the local and regional level due to the inflammatory effect and inability to visualize small lesions (<0.5 cm). Ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration of residual neck masses after chemoradiation has been investigated. While sensitivity and positive predictive value are reasonably high, specificity and negative predictive value lack accuracy.

Since salvage surgery after chemoradiation is possible only in a limited number of patients and has a high complication rate even when vascularized flaps are used liberally and high rate of further recurrences after salvage, the question is what is the outcome? Goodwin in 2000 described a clear influence of pretreatment stage on outcome [2]. Stage I and II have a 70 % outcome, with good quality of life in 60–85 % of patients and low surgical complication rate. In the more advanced stages, this picture deteriorates considerably. In stage III, patients have only 33 % 2-years survival with markedly less quality of life and 40 % complications. For stage IV, this is still worse, with less than 25 % 2-years survival and even lower quality of life. Swallowing and speech problems were very common after salvage surgery. Deaths related to surgery were extremely low in all stages.

Although salvage surgery also exists for oral cancer patients who recur after chemoradiotherapy, those who need salvage for laryngeal cancer benefit most, followed by hypopharynx and oropharynx cancer patients. Several reports have focused on these specific sites, as well as the neck only [3–11, 11a, 12–19]. Overall survival after total laryngectomy for salvage after chemoradiation is usually in the order of 40–50 % at 5 years [7–10]. It is notable that Forastiere et al. in their report on long-term results of RTOG 91–11, state that “integrating chemotherapy and conservation laryngeal surgery in selected patients with T3 disease warrants investigation. Our exploratory analysis of the outcome after salvage laryngectomy for patients receiving induction or concomitant chemotherapy suggests that early identification of patients who will eventually experience failure with nonsurgical therapy may be important for long-term survival” [11].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree