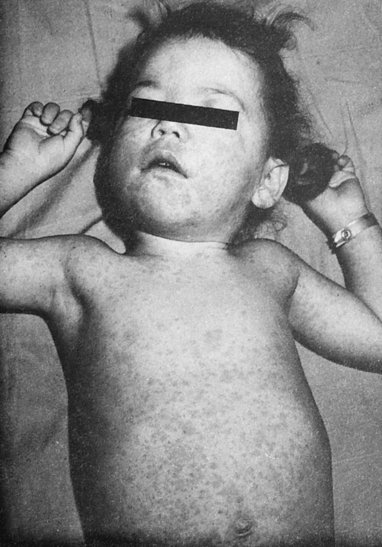

At the conclusion of this chapter, the reader should be able to: • Describe the etiology and epidemiology of rubella (German measles) infection. • Explain the signs and symptoms of acquired and congenital rubella infection. • Compare the immunologic manifestations of acquired and congenital rubella infection. • Explain the laboratory diagnostic evaluation of rubella infection. • Summarize the epidemiology and laboratory diagnosis of rubeola (measles). • Analyze a representative case study. • Correctly answer case study related multiple choice questions. • Be prepared to participate in a discussion of critical thinking questions. • Describe the principle, results, limitations, and clinical applications of the passive latex agglutination test for Rubella. The clinical presentation of acquired rubella is usually mild. The clinical manifestations of infection usually begin with a prodromal period of catarrhal symptoms, followed by involvement of the retroauricular, posterior cervical, and postoccipital lymph nodes, and finally by the emergence of a maculopapular rash on the face and then on the neck and trunk (Figs. 24-1 and 24-2). A temperature less than 34.4° C (94° F) is usually present. In older children and adults, self-limiting arthralgia and arthritis are common. Rubella infection is usually a mild, self-limiting disease with only rare complications in children and adults. In pregnant women, however, especially those infected in the first trimester, rubella can have devastating effects on the fetus (Fig. 24-3). In utero infection can result in fetal death or manifest as rubella syndrome, a spectrum of congenital defects. About 10% to 20% of infants infected in utero fail to survive beyond 18 months. The point in the gestation cycle at which maternal rubella infection occurs greatly influences the severity of congenital rubella syndrome (Table 24-1); the extent of congenital anomalies varies from one infant to another. Some infants manifest almost all the defects associated with rubella, whereas others exhibit few, if any, consequences of infection. Clinical evidence of congenital rubella infection may not be recognized for months or even years after birth. Table 24-1 Manifestation of Anomalies in Maternal Rubella

Rubella and Rubeola Infections

Rubella

Etiology of Rubella

Signs and Symptoms of Rubella Infection

Acquired Rubella Infection

Congenital Rubella Infection

Period of Gestation

Risk of Anomaly

Prospective Studies

First trimester

≈25%

Second trimester

First month

Less than (>)1%

Second month

≥25%

Third month

≥10%

Serologically Confirmed Cases of Maternal Infection ![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access