This chapter describes how investigators obtain estimates of risk by observing the relationship between exposure to possible risk factors and the subsequent incidence of disease. It describes methods used to determine risk by following groups into the future and also discusses several ways of comparing risks as they affect individuals and populations.

Chapter 6 describes methods of studying risk by looking backward in time.

When Experiments Are Not Possible or Ethical

The effects of most risk factors in humans cannot be studied with experimental studies. Consider some of the risk questions that concern us today: Are inactive people at increased risk for cardiovascular disease, everything else being equal? Do cellular phones cause brain cancer? Does obesity increase the risk of cancer? For such questions, it is usually not possible to conduct an experiment. First, it would be unethical

to impose possible risk factors on a group of healthy people for the purposes of scientific research. Second, most people would balk at having their diets and behaviors constrained by others for long periods of time. Finally, the experiment would have to go on for many years, which is difficult and expensive. As a result, it is usually necessary to study risk in less obtrusive ways.

Clinical studies in which the researcher gathers data by simply observing events as they happen, without playing an active part in what takes place, are called

observational studies. Most studies of risk are observational studies and are either

cohort studies, described in the rest of this chapter, or case-control studies, described in

Chapter 6.

Cohort Studies

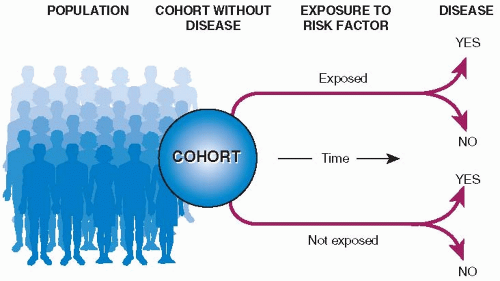

The basic design of a cohort study is illustrated in

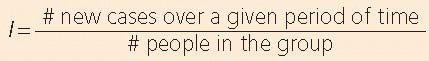

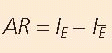

Figure 5.1. A group of people (a cohort) is assembled, none of whom has experienced the outcome of interest, but all of whom could experience it. (For example, in a study of risk factors for endometrial cancer, each member of the cohort should have an intact uterus.) Upon entry into the study, people in the cohort are classified according to those characteristics (possible risk factors) that might be related to outcome. For each possible risk factor, members of the cohort are classified either as

exposed (i.e., possessing the factor in question, such as hypertension) or

unexposed. All the members of the cohort are then observed over time to see which of them experience the outcome, say, cardiovascular disease, and the rates of the outcome events are compared in the exposed and unexposed groups. It is then possible to see whether potential risk factors are related to subsequent outcome events. Other names for cohort studies are

incidence studies, which emphasize that patients are followed over time; prospective studies, which imply the forward direction in which the patients are pursued; and longitudinal studies, which call attention to the basic measure of new disease events over time.

The following is a description of a classic cohort study that has made important contributions to our understanding of cardiovascular disease risk factors and to modern methods of conducting cohort studies.

Prospective and Historical Cohort Studies

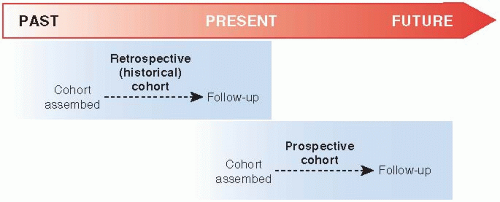

Cohort studies can be conducted in two ways (

Fig. 5.2). The cohort can be assembled in the present and followed into the future (a

prospective cohort study), or it can be identified from past records and followed forward from that time up to the present (a

retrospective cohort study or a

historical cohort study). The Framingham Study an example of a prospective cohort study. Useful retrospective cohort studies are appearing increasingly in the medical literature because of the availability of large computerized medical databases.

Prospective Cohort Studies

Prospective cohort studies can assess purported risk factors not usually captured in medical records, including many health behaviors, educational level, and socioeconomic status, which have been found to have important health effects. When the study is planned before data are collected, researchers can be sure to collect information about possible confounders. Finally, all the information in a prospective cohort study can be collected in a standardized manner that decreases measurement bias.

Historical Cohort Studies Using Medical Databases

Historical cohort studies can take advantage of computerized medical databases and population registries that are used primarily for patient care or to track population health. The major advantages of historical cohort studies over classical prospective cohort studies are that they take less time, are less expensive, and are much easier to do. However, they cannot undertake studies of factors not recorded in computerized databases, so patients’ lifestyle, social standing, education, and other important health determinants usually cannot be included in the studies. Also, information in many databases, especially medical care information, is not collected in a standardized manner, leading to the possibility of bias in results. Large computerized databases are particularly useful for studying possible risk factors and health outcomes that are likely to be recorded in medical databases in somewhat standard ways, such as diagnoses and treatments.

Advantages and Disadvantages of Cohort Studies

Well-conducted cohort studies of risk, regardless of type, are the best available substitutes for a true experiment when experimentation is not possible. They follow the same logic as a clinical trial and allow measurement of exposure to a possible risk factor while avoiding any possibility of bias that might occur if exposure were determined after the outcome was already known. The most important scientific disadvantage of cohort studies (in fact, all observational studies) is that they are subject to a great many more potential biases than are experiments. People who are exposed to a certain risk factor in the natural course of events are likely to differ in a great many ways from a comparison group of people not exposed to the factor. If some of these other differences are also related to the disease in question, they could confound any association observed between the putative risk factor and the disease.

The uses, strengths, and limitations of the different types of cohort studies are summarized in

Table 5.2. Several of the advantages and disadvantages apply regardless of type. However, the potential

for difficulties with the quality of data is different for the three. In prospective studies, data can be collected specifically for the purposes of the study and with full anticipation of what is needed. It is thereby possible to avoid measurement biases and some of the confounders that might undermine the accuracy of the results. However, data for historical cohorts are usually gathered for other purposes—often as part of medical records for patient care. Except for carefully selected questions, such as the relationship between vaccination and autism, the data in historical cohort studies may not be of sufficient quality for rigorous research.

Prospective cohort studies can also collect data on lifestyle and other characteristics that might influence the results, and they can do so in standard ways. Many of these characteristics are not routinely available in retrospective and case-cohort studies, and those that are usually are not collected in standard ways.

The principal disadvantage of prospective cohort studies is that when the outcome is infrequent, which is usually so in studies of risk, a large number of people must be entered in a study and remain under observation for a long time before results are available. Having to measure exposure in many people and then follow them for years is inefficient when few ultimately develop the disease. For example, the Framingham Study of cardiovascular disease (the most common cause of death in America) was the largest study of its kind when it began. Nevertheless, more than 5,000 people had to be followed for several years before the first, preliminary conclusions could be published. Only 5% of the people had experienced a coronary event during the first 8 years. Retrospective and case-cohort studies get around the problem of time but often sacrifice access to important and standardized data.

Another problem with prospective cohort studies results from the people under study usually being “free living” and not under the control of researchers. A great deal of effort and money must be expended to keep track of them. Prospective cohort studies of risk, therefore, are expensive, usually costing many millions, sometimes hundreds of millions, of dollars.

Because of the time and money required for prospective cohort studies, this approach cannot be used for all clinical questions about risk, which was a major reason for efforts to find more efficient, yet dependable, ways of assessing risk, such as retrospective and case-cohort designs. Another method, case-control studies, is discussed in

Chapter 6.

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access