© Springer Science+Business Media New York 2016

Ellen F. Manzullo, Carmen Esther Gonzalez, Carmen P. Escalante and Sai-Ching J. Yeung (eds.)Oncologic EmergenciesMD Anderson Cancer Care Series10.1007/978-1-4939-3188-0_77. Rheumatologic/Orthopedic Emergencies

(1)

Department of General Internal Medicine, Unit 1465, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, 1515 Holcombe Boulevard, Houston, TX 77030, USA

Keywords

Paraneoplastic syndromeSeptic arthritisCrystal-induced arthritisPyomyositisMusculoskeletal tumorsOsteoporosisOsteoporotic fracturesVasculitis and vasculopathiesRaynaud phenomenonDigital ischemiaChapter Overview

Patients with cancer frequently present with signs and symptoms of musculoskeletal and rheumatic diseases. Acute joint pain with swelling is the most common indication of an emergency rheumatologic evaluation. Individuals with monoarthritis should be evaluated immediately to rule out septic arthritis, as patients with cancer are at high risk for infection because of the immunosuppressive effects of their cancer and its treatment. Furthermore, use of empiric broad-spectrum antibiotics should be initiated to prevent loss of joint function. Acute crystal-induced arthritis—either gout or calcium pyrophosphate crystal deposition (CPPD) disease—is one of the most common causes of painful, swollen joints in patients with cancer and is often triggered by dehydration. Paraneoplastic syndrome s can present as oligoarthritis or polyarthritis and are often diagnoses of exclusion. Other rheumatologic paraneoplastic syndromes, such as myositis, vasculitis, and tendinitis/fasciitis, can lead to significant morbidity. Skeletal complications may be caused by local or metastatic tumor invasion, pathologic and osteoporotic fractures and osteonecrosis; and are usually associated with severe pain. In addition, cancer patients with pre-existing rheumatologic diseases can experience flare-ups of those diseases that require urgent intervention. All of these scenarios require physicians to be able to recognize the indications for emergency evaluation and treatment to prevent complications and ensure that patients continue to benefit from optimal cancer treatment.

Introduction

Musculoskeletal symptoms are common indications for office visits. Such symptoms in cancer patients can be the first signs of an emergency condition that requires immediate evaluation and intervention to prevent compromise of their cancer treatment or potentially life-threatening outcomes. Primary care physicians, emergency room staff, and oncologists are on the front line of evaluation of such patients. Being able to identify such conditions and provide the initial work-up for proper differential diagnosis and treatment in a timely manner is vital to preserving function and prolonging survival. This chapter is focused on the common bone, joint, and muscle symptoms in cancer patients.

Arthritis

Joint pain with swelling is the most common indication for rheumatologic evaluation in the emergency setting. Pain in a joint must be distinguished from pain in the adjacent soft tissue. Arthritis is associated with joint swelling, pain, and decreased range of motion, whereas soft tissue pain and swelling around the joint can be palpated, extending beyond the joint and often leaving the range of motion of the joint unaffected. Arthritis can occur in a single joint (monoarthritis), a few joints (oligoarthritis), or multiple joints (polyarthritis).

Monoarthritis

Causes of acute monoarthritis can overlap with those of oligoarthritis and polyarthritis. However, a cancer patient presenting with a single hot, swollen, tender joint with restricted range of motion has a true rheumatologic emergency, as cancer patients often undergo immunosuppressive treatment, which predisposes them to septic arthritis. If left untreated, the infection can lead to rapid destruction of the joint and irreversible loss of function. Therefore, the initial work-up for monoarthritis should focus on evaluation for a possible infection with imaging and joint fluid aspiration. Main differential diagnoses include crystal-induced arthritis, osteonecrosis, flare-up of osteoarthritis, and direct involvement of bone malignancies near joints.

Septic Arthritis

The true incidence of septic arthritis in patients with cancer is unknown. Individuals with cancer and those undergoing active treatment of cancer are at increased risk for septic arthritis because they may have indwelling catheters, open wounds from invasive procedures, or decreased immune function induced by their cancer or its treatment. Glucocorticoids , which are frequently given to patients with hematologic malignancies, can depress immunity, lower neutrophil synovial counts, and reduce function. Non-cancer-related causes of septic arthritis include pre-existing joint disease that predisposes the joint to bacterial colonization, history of rheumatoid arthritis, and diabetes mellitus.

The most commonly infected joint is the knee, although other joints can be involved, including the shoulder, wrist, and ankle and finger joints. The affected joint is usually swollen, warm, and tender. Staphylococcus aureus is the most common infecting pathogen; streptococci and gram-negative bacilli are also common.

Bacterial infection of joints can be the initial presentation of acute leukemia , especially in children, or a complication of leukemia treatment. Authors also have reported septic arthritis in patients with multiple myeloma. In a case study of 17 patients in whom acute infection was the first manifestation of multiple myeloma, 35 % of the patients had septic arthritis, mostly involving the knee. Streptococcus pneumoniae was isolated from two thirds of the patients, and bacteremia was common. The risk of infection in patients with multiple myeloma is highest during the first months after initial diagnosis and in those with renal dysfunction. Of interest, patients with colon cancer can have septic arthritis caused by Clostridium septicum , which can be the initial manifestation of their malignancy. Radiation therapy is implicated to play a causative role in the development of septic arthritis in adjacent joints, such as septic arthritis of the hip joint after radiation therapy for cervical carcinoma or of the shoulder or sternoclavicular joint after radiation therapy for breast carcinoma.

Patients with hematologic malignancies are also at risk for invasive fungal infections in joints, which are most common in those with acute myeloid leukemia. Candida species are clinically significant pathogens in these patients. Cancer patients who experience neutropenia and candidemia have much higher rates of visceral dissemination and mortality than do patients who do not have these complications. Chronic disseminated candidiasis is most often observed in neutropenic patients with hematologic malignancies. Other risk factors for fungal infection are similar to those for bacterial infection.

The overall incidence of fungal arthritis has decreased significantly owing to the prophylactic use of fluconazole in neutropenic patients. However, fungal infections with non-albicans Candida spp. such as Candida krusei, which is resistant to treatment with fluconazole, have become more common over the past decade. Clinically, molds can be the infecting pathogens for fungal arthritis but at a lower frequency than with fungi. These molds include Aspergillus fumigatus, non-fumigatus Aspergillus species, unspecified Aspergillus spp., Fusarium species, zygomycetes, Scedosporium apiospermum, and Exserohilum species.

Atypical mycobacterial infection is a concern for immunocompromised patients. Mycobacterium haemophilum is emerging as an infecting pathogen in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome or hematologic malignancies and recipients of organ or bone marrow transplants. Of 23 patients infected with M. haemophilum reported in a single institution over 10 years, all but 1 had known underlying immunosuppression. Four patients had septic arthritis or osteomyelitis. Initial atypical mycobacterial staining is often unrevealing, and specimens should be cultured for up to 8 weeks because of the slow growth of these pathogens. Once confirmed, treatment should be started accordingly .

Crystal-Induced Arthritis

A significant differential diagnosis for a single red, swollen, tender joint is crystal-induced arthritis. The most common crystal precipitation in a joint involves monosodium urate. Although the first metatarsophalangeal joint in the big toe is commonly involved, acute gouty arthritis can occur in a single joint in a finger, in the knee, or in the elbow. Involvement of multiple joints also can occur, especially in patients with a history of gout.

Clinically, patients complain of acute onset (over 6–12 h) of intense joint pain, redness, warmth, and swelling. Concurrent serum uric acid levels can be within normal limits in these patients and do not eliminate gout as a diagnosis. Acute onset of gouty arthritis can be caused by increased systemic production of uric acid after a change in diet or accelerated purine breakdown after cancer treatment or by decreased secretion of uric acid caused by impaired renal function. Other risk factors include dehydration, immobilization, previous joint injury, and history of osteoarthritis.

In elderly patients with rapid onset of pain and swelling in a joint and no prior history of gout or hyperuricemia, the diagnosis may be CPPD disease caused by calcium pyrophosphate dehydrate deposition in the joint. The most commonly affected joints are the knees, wrists, and shoulders. CPPD crystals can be observed in the synovial fluid. Detection of chondrocalcinosis on X-rays supports this diagnosis. Although chondrocalcinosis is often asymptomatic, dehydration or prolonged immobilization can cause progression to arthritis from CPPD disease.

Arthritis Associated with Malignancy

Authors have reported direct involvement of arthritis in one or a few joints in both patients with primary non-Hodgkin lymphoma and patients with leukemia, particularly children with leukemia. Researchers have made similar observations in adult patients at our institution. Clinically, the involved joints are red, warm, swollen, and tender, mimicking the symptoms of septic arthritis. Magnetic resonance imaging can demonstrate typical lesions involving the bone and joint. Primary non-Hodgkin lymphoma also can involve the lumbar vertebral bodies, leading to radicular compression or cauda equina syndrome. Metastasis of solid tumors to joints is very rare, although direct metastasis of lung and thyroid cancer to a single shoulder joint has occurred; this is often associated with poor prognosis. Furthermore, authors have reported transarticular spread of Ewing sarcoma mimicking septic arthritis. In cases of direct metastasis to joints, imaging studies alone may be insufficient, and image-guided biopsy may be required for a definitive diagnosis.

Diagnosis and Treatment

When a patient presents with monoarthritis, a baseline X-ray of the affected joint should be obtained. Joint aspiration should be performed on an emergency basis, and synovial fluid analysis is the best diagnostic test to perform during the initial steps of evaluation. Blood culture should be performed if septic arthritis is suspected. Aspirated synovial fluid should be evaluated for the degree of inflammation using cell counts and differential analysis; gram, fungal, and acid-fast bacilli stains should be used to detect relevant pathogenic micro-organisms; and microscopic analysis should be performed to detect crystals. Synovial fluid also should be sent immediately for cultures for bacterial, fungal, and mycobacterial species. Synovial cell counts in neutropenic patients can be misleadingly low, especially in those with fungal or atypical mycobacterial infections. If a patient is neutropenic and has a low synovial cell count, a repeat arthrocentesis and cell count as well as micro-organism staining and adequate culturing are of paramount importance to confirming the clinical suspicion.

Because many patients with cancer have low platelet counts secondary to their underlying malignancy or its treatment, ultrasonography, if available, should be used to guide arthrocentesis and avoid excessive needle manipulation and potential bleeding. Furthermore, ultrasonography may reveal the presence of synovial fluid before the joint aspiration or help identify the characteristics of a specific type of crystal-induced arthropathy, such as CPPD crystals in CPPD disease cases and tophi in gout cases. A suspected infection of a prosthetic joint always should be referred to an orthopedic surgeon. In a patient with a very low platelet count, needle aspiration can be performed immediately after platelet transfusion.

Ideally, treatment of suspected septic arthritis with antibiotics should be started soon after arthrocentesis. However, among patients with cancer, treatment with empiric antibiotics is often initiated before joint aspiration in those with life-threatening neutropenic fever. Information from blood cultures, urinalysis, and/or bronchial lavage can be used to adjust antibiotic treatment. Conventional antibiotics should be administered intravenously for 2 weeks or until symptoms improve and then orally for 4 weeks. A septic joint should be aspirated to dryness as often as required. Empiric antifungal treatment with voriconazole and intravenous amphotericin for coverage of non-albicans Candida infections should be considered for patients who have been receiving prophylactic antibiotic and antifungal treatment with fluconazole.

The conventional treatment of septic arthritis is antimicrobial therapy alone. However, a small trial in pediatric patients with septic arthritis demonstrated that short-term use (4 days) of dexamethasone at the beginning of antibiotic treatment led to markedly improved symptoms and markers of inflammation, shortened hospital stays, and no increase in adverse events. The efficacy and safety of glucocorticoids in managing septic arthritis in cancer patients must be established in formal studies.

In general, treatment of an acute gout attack should start as soon as possible after the attack begins, preferably within hours of symptom onset. Rapid, complete resolution of symptoms is associated with early treatment. Administration of an anti-inflammatory agent at a full recommended dose should be started, and the patient should continue receiving treatment for the duration of the attack, usually at a reduced dose once a significant response is observed. Several classes of anti-inflammatory agents have proven to be effective for the treatment of acute gout, including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, colchicine, glucocorticoids, and monoclonal antibodies against inflammatory cytokines. When oral colchicine is used, hourly accelerated dosing should be avoided, as most patients experience severe diarrhea with no added benefit. Low-dose oral colchicine, with an initial dose of 1.2 mg followed 1 h later by a dose of 0.6 mg, in the first day of treatment has exhibited similar efficacy to high-dose colchicine.

The challenging issues in cancer patients with acute gout attacks include low platelet counts, renal and hepatic impairment, and polypharmacy. Use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs should be avoided in patients with low platelet counts and impaired renal function. The colchicine dose should be lowered in patients with impaired renal or hepatic function and those concurrently taking a drug that decreases the availability of CYP3A4 to prevent toxicity. When nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and colchicine are contraindicated, treatment with systemic and intra-articular glucocorticoids is effective. When a co-existing joint infection or skin infection overlaying the joint cannot be ruled out, intra-articular use of glucocorticoids should be avoided. Although long-term prophylaxis with oral allopurinol is usually not initiated during an acute gout attack, it may be necessary for patients anticipated to have increased purine metabolism and frequent gout attacks during chemotherapy. This can be done safely after patients receive anti-inflammatory agents and experience marked improvement of their acute symptoms. They should also continue receiving a low-dose anti-inflammatory agent to prevent further acute gout flare-ups induced by the initiation of treatment with allopurinol. Anti-inflammatory cytokines such as anti-interleukin-1 have yet to be studied extensively in cancer patients, although they are promising because of their rapid reduction of inflammation.

Oligoarthritis and Polyarthritis

A small percentage of cancer patients with septic arthritis present with polyarticular symptoms, reflecting bacteremia and diminished resistance to infection. Painful polyarthritis can be the initial sign of an undiagnosed malignancy. Oligoarthritis has occurred in patients with lung cancer as well as patients given intravesical bacillus Calmette-Guérin for bladder cancer. Although these symptoms can be self-limiting, they often necessitate additional treatment with anti-inflammatory agents, such as glucocorticoids. Polyarthritis can also be an active flare-up of a co-existing rheumatologic disease , such as rheumatoid arthritis and psoriatic arthritis, in patients with cancer. In this setting, chemotherapy for the underlying malignancy often offers good control of the arthritic symptoms of autoimmune diseases, although additional treatment with immunosuppressive drugs may be needed.

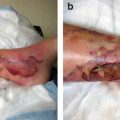

Paraneoplastic Syndrome Associated with Polyarthritis

Carcinomatous polyarthritis is a rare paraneoplastic disorder that has been associated with a variety of solid tumors, including bronchogenic, lung, and colon cancer, and with hematologic malignancies. It is often characterized by sudden onset of asymmetric migratory arthritis involving a few joints. Large joints are involved more often than small ones. Synovitis is not associated with joint erosions, nodules, or deformities. The pathogenesis of carcinomatous polyarthritis is not well understood but is thought to involve autoimmune processes. In general, oligoarthritis and polyarthritis resolve after successful treatment of the malignancy with chemotherapy or tumor resection. For patients with significant joint pain, symptom treatment with steroid injections if just a few joints are involved or low to intermediate doses of oral glucocorticoids can offer good symptom control. Remitting seronegative symmetrical synovitis with pitting edema (RS3PE ) is a syndrome with the typical feature of subcutaneous pitting edema that affects both hands and feet. Symmetric polyarthritis of the peripheral joints mimics rheumatoid arthritis. However, the tenosynovitis associated with RS3PE is not associated with other typical features of rheumatoid arthritis, such as rheumatoid factor, joint erosions, and subcutaneous nodules. Pathogenically, researchers have found serum concentrations of vascular endothelial growth factor that were markedly increased in patients with active RS3PE. Vascular endothelial growth factor promotes synovial inflammation and vascular permeability in patients with RS3PE, suggesting that RS3PE can be classified as a vascular endothelial growth factor-associated disorder. RS3PE also has been associated with malignancy. In a review of the published literature, authors reported a total of 59 patients with 32 different malignancies diagnosed with RS3PE. Eighteen of these malignancies were solid tumors, including prostate cancer, gastrointestinal cancer, lung cancer, breast cancer, ovarian cancer, bladder carcinoma, endometrial cancer, cryptogenic hepatocellular carcinoma, and fibrohistocytoma, whereas 11 were hematologic malignancies, including non-Hodgkin lymphoma, leukemia, and myelodysplastic syndrome. Some patients had malignancies of unknown origin. Overall, researchers have suggested that malignancies may occur in 20–54 % of patients with RS3PE. Patients with both RS3PE and cancer often have more dramatic systemic symptoms than do patients with RS3PE alone. Also, RS3PE in the former patients is often refractory to therapy with glucocorticoids, whereas that in the latter patients is not. Signs and symptoms of RS3PE may improve after tumor removal.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree