Approximately 15% of soft tissue sarcomas (STS) occur in the retroperitoneum, and thus, there are only approximately 1600 new retroperitoneal sarcomas (RPS) in the United States per year.1 In large series, the average age is between 50 and 60 years old and there are equal numbers of men and women.2–4 RPS are frequently asymptomatic until reaching large sizes, and thus the average size of tumors is often greater than 10 to 15 cm. The optimal local therapy for RPS includes surgical resection with negative microscopic margins, but many if not most tumors cannot be removed in this fashion. Even with complete surgical resection, local recurrence rates can approach 50% or greater. An important aspect of RPS is that even though many of these tumors are large and high grade, the metastasis rate is significantly lower than that of extremity and truncal tumors, with the most common sites of metastasis being the lung and liver.5 Thus, local recurrence is the leading cause of death in RPS patients. The role of preoperative or postoperative radiation therapy in reducing local recurrence of extremity and trunk STS is firmly established by prospective, randomized trials.6–8 In contrast RPS are generally large and abut radiation-sensitive organs such as the kidney, liver, and small bowel, making the delivery of adequate doses of preoperative radiation difficult.9 The role of adjuvant chemotherapy in reducing local recurrence rates in any location is modest at best.10 More recent studies of more aggressive surgery and advanced radiation techniques have suggested that local recurrence can potentially be reduced, but these strategies are debatable. Newer chemotherapies and targeted agents may also play a role in the reduction of local recurrence rates. This chapter summarizes the current management of RPS with emphasis on surgical resection and radiation therapy.

In fact, the histologic grade of STS is determined by morphological features including necrosis, mitoses, and degree of differentiation.11 The World Health Organization (WHO) has defined over 50 subtypes based on the histologic appearance of the tumor tissue.12 About two-thirds of RPS are either liposarcomas or leiomyosarcomas, with the remaining tumors distributed among a large variety of other histologic subtypes.4 It should be noted that each histologic subtype of STS may have a unique tumor biology, radiological appearance, and clinical behavior. For example, well-differentiated liposarcomas, chromosome 12q is often amplified resulting in overexpression of MDM2 and CDK4.13 These tumors have a characteristic appearance on computed tomography (CT) scans as large fatty tumors with internal septations (Fig. 27-1A).14 As these well-differentiated liposarcomas enlarge, they can develop more solid areas in a process known as dedifferentiation (Fig. 27-1B). In a study by the M.D. Anderson Cancer Center, CT scan features accurately identified 60 out of 60 (100%) of well-differentiated liposarcomas but was less accurate in determining areas of hypercellular well-differentiated liposarcoma from areas of dedifferentiation.15

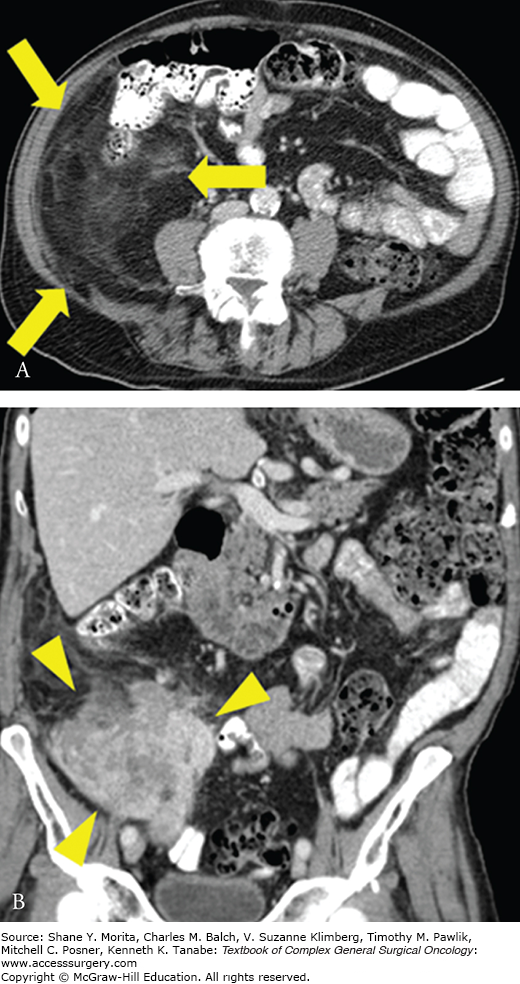

FIGURE 27-1:

Well-differentiated/dedifferentiated liposarcoma. A. Axial image of right retroperitoneal well-differentiated liposarcoma, which appears as an area of abnormal appearing fat (arrows). B. Coronal image showing area of dedifferentiation, which appears as a more solid area within or adjacent to abnormal appearing fat (arrowheads).

Patients often present with an asymptomatic abdominal mass or have an incidental retroperitoneal mass identified on radiological imaging.4 When symptoms do occur, they can be caused by (1) mass effect on bowel leading to abdominal discomfort, early satiety, weight loss, or bowel obstruction, (2) compression of the inferior vena cava or iliac veins causing leg swelling, or (3) impingement of nerves causing lower extremity pain or weakness. In one series of 500 patients, 80% of patients presented with an abdominal mass, 42% with lower extremity neurologic symptoms, and 37% with pain.4

The vast majority of patients present without any obvious risk factor, but a detailed history should be performed to exclude possible etiologies. Prior radiation can result in a radiation-associated sarcoma, with the frequency of radiation-associated sarcomas increasing with dose and with the postradiation observation period.16 Other risk factors include genetic disorders such as neurofibromatosis 1 (NF1), and NF1 patients have about a 15% lifetime risk of developing a malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor (MPNST).17

Most unifocal tumors in the retroperitoneum that do not arise from an adjacent organ will either be a RPS or a benign soft tissue tumor (e.g., Schwannoma). Other malignancies in the differential diagnosis include primary germ cell tumor, metastatic testicular cancer, and lymphoma. Patients with metastatic testicular cancer may have a testicular mass identified on physical examination or scrotal ultrasound. Patients with primary germ cell or testicular tumors will often have an elevated β-human chorionic gonadotropin or α-fetoprotein level. Patients with lymphoma may have B symptoms (fever, night sweats, and weight loss), additional lymphadenopathy, or an elevated LDH. There is no blood test that is generally elevated in patients with RPS.

A CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis should be obtained with oral and intravenous contrast to fully evaluate the tumor and its proximity to adjacent organs, vessels, and nerves.18 MRI may be of benefit in certain circumstances such as determining the proximity of a tumor to major nerves or in patients with a contraindication to CT scan intravenous contrast. A minority (10% to 20%) of patients with RPS present with metastatic disease, and the most common sites of metastases are the lung and liver.5 Thus for high-grade tumors, a chest CT is obtained in addition to the abdomen/pelvis CT. For low-grade tumors, metastasis is uncommon and so a chest x-ray is sufficient. The role of positron emission tomography (PET) or PET/CT scans in the evaluation of sarcoma patients has yet to be defined. Many sarcomas do show increased 2-deoxy-2-[(18)F] fluoro-D-glucose (18)F-FDG uptake and changes in (18)F-FDG uptake often correlate with treatment response.19

However, the role for image-guided biopsy of retroperitoneal tumors is somewhat controversial. The advantages of image-guided biopsy include the high likelihood of establishing a tissue diagnosis and the ability to give preoperative treatment, if this is being considered. Core needle biopsy of RPS will yield a correct diagnosis of sarcoma in over 90% of cases, although there is lower accuracy in determining the correct histologic subtype and tumor grade.20,21 There are theoretical risks of needle track or intraperitoneal seeding of tumor as well as bleeding, but these risks are very low and can be minimized by avoiding a transperitoneal approach. For patients presenting after receiving a biopsy showing sarcoma, the biopsy material should be reviewed by an experienced sarcoma pathologist given that about 6% to 10% of cases originally designated as sarcoma are in fact not sarcoma and 14% to 27% are initially assigned the incorrect histologic subtype.22,23

The 2010 7th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) Cancer Staging Manual has established a staging system for STS, which includes characteristics of the primary tumor (T, size and depth), regional lymph nodes (N, negative or positive), distant metastases (M, absent or present), and grade (G1-G3).24 Some investigators have questioned the applicability of the AJCC staging system for STS given the system does not take into account the varied histological subtypes and anatomic locations of STS. Nathan et al in analysis of 1365 RPS patients in the SEER database found that tumor grade, invasion of adjacent structures, and histologic subtype predicted survival after RPS resection while tumor size had no impact on survival.25 Anaya et al also argued that a histology-based RPS prognostic system has major advantages over the AJCC staging system.26 Kattan et al at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) developed a nomogram to predict survival following STS resection, which includes site and histologic subtype as predictor variables,27 and two nomograms developed specifically for RPS have recently been described.28,29 Prognostic factors in these nomograms include age, grade, histologic subtype, size, primary versus recurrent disease, multifocality, and completeness of resection (R0/R1 vs. R2).

Surgical resection is the primary treatment for RPS.

Table 27-1 summarizes five large surgical series of RPS, including two reports from MKSCC (New York, the United States), one report from the Insituto Nazionale Tumori (Milan, Italy), a multi-institution report from France, and a two-institution report from the Insituto Nazionale Tumori and Institut Gustave Rousssy (Villejuif, France).2–4,30 All these series include only patients who presented with primary tumors. The median size of tumors was up to 18 cm. Complete gross resection rates ranged from 75% to 93%, and contiguous organs resection was required in 58% to 77% of cases. The proportion of tumors resected with a negative microscopic varied between 47% and 59%. Of note, the negative microscopic margin rate may be misleading given the ability to detect a positive microscopic margin depends highly on (1) whether the surgeon orients the specimen for the pathologists and identifies the location or locations of the closest margin and (2) how extensively the pathologist examines these often very large specimens.

Selected Surgical Series

| Institution/Group | MSKCC | MSKCC | INT | Multi-institution | INT and IGR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| New York | New York | Milan | France | Milan and Villejuif | |

| Time period | 1982–1997 | 1982–2010 | 1985–2007 | 1985–2005 | 2000–2008 |

| Year published | 1998 | 2104a | 2009 | 2009 | 2010 |

| Median follow-up (month) | 28 | 52 | 58 | 53 | 37 |

| Number of patients | 231 | 675 | 288 | 382 | 249 |

| Mean or median age | NR | 60 | 55 | 57 | 55 |

| Primary tumors | 100% | 100% | 67% | 100% | 100% |

| Mean or median size | >10 cm | 17 cm | 16 | 18 | 17 |

| Intermediate- or high-grade | 60% | 64% | 71% | 64% | 67% |

| Complete gross resection | 80% | 85% | 89% | 75% | 93% |

| Contiguous organ resection | 77% | 58% | 71% | 67% | NR |

| Negative microscopic margin | 59% | 50% | NR | 47% | NR |

| Mortality | 4% | 3.4% | NR | 3% | 3% |

| Adjuvant radiation | NR | 14% | 31% | 32% | 36% |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | NR | 16% | 32% | 17% | 37% |

| 5-year local recurrence | 41% | 39% | 29%–48% | 49% | 22% |

| 5-year distant recurrence | 21% | 24% | 13%–22% | 34% | 24% |

| 5-year overall survival | 54% | 59% | 51%–60% | 57% | 65% |

As noted earlier, the primary problem with RPS is local recurrence, and patients who ultimately succumb to RPS more commonly die of local recurrence than distant metastasis. The estimated 5-year local recurrence rates in the five largest reported series varied between 29% to 49%, but these can vary significantly depending on length of follow-up and rates may be significantly higher in smaller series. The median time to local recurrence after RPS resection is about 22 months31 but well-differentiated liposarcomas can recur beyond 5 and 10 years after surgical resection. Five-year distant recurrence rates varied between 13% to 24% and 5-year overall survival rates ranged from 51% to 65%.

Some series have examined prognostic factors for both local and distant recurrence. Some surgical series have examined prognostic factors for local recurrence and found histologic subtype, grade, radiation, and type of surgery to be prognostic factors.2–4,32 Only one study2 found margin to be prognostic while another study did not.4 Prognostic factors for distant recurrence and overall survival prognostic factors (found in one or more studies) included histologic subtype, grade, complete gross resection, and radiation therapy.2–4,32–34

For tumors where complete gross resection is possible, leaving a negative microscopic margin around the entire tumor can be challenging. The EORTC-Soft Tissue and Bone Sarcoma Group recently described a standardized surgical approach to RPS.35 The anterior surface of these tumors is often covered by peritoneum and organs, which can be resected with relatively low morbidity (e.g., colon, tail of pancreas, spleen, and kidney) enabling a negative anterior margin. In other instances, the anterior margin may be the head of the pancreas and duodenum, and performance of a pancreaticoduodenectomy may significantly increase morbidity. Laterally, the peritoneum and the transversalis fascia can generally be left on the tumor as margin. Medially, tumors can generally be dissected of the aorta and inferior vena cava, leaving adjacent areolar tissue on the tumor as margin. The posterior margin of these tumors often abuts retroperitoneal fat and the psoas musculature, where obtaining negative margins requires visualization and sharp dissection due to the lack of anatomic dissection planes. Thus, tumors should be dissected circumferentially from anterior to posterior to allow visualization and sharp dissection rather than working on the posterior aspect of the tumor through a limited hole. Resection of major vessels, nerves, and bone is generally not necessary unless there is direct invasion. Major arteries can usually be dissected free leaving adventitia on the tumor, major nerves can be dissected free leaving epineurium on tumor, and bone can be dissected free leaving periosteum on tumor.

The aggressiveness of RPS surgery, particularly in the resection of adjacent organs and tissues, has been a topic of significant debate. Gronchi et al from the Istituto Nazionale del Tumor in Milan retrospectively examined 288 patients with primary RPS surgically resected between 1985 and 2007.3 Prior to 2002, adjacent organs were generally only resected if there was direct involvement by tumor. From 2002 onward, a more aggressive policy was instituted with resection of adjacent organs and tissues. Radiation was delivered in about 30% of patients. Five-year actuarial local recurrence was 48% in the less aggressive surgery group and 29% in the more aggressive surgery group. Thus the authors argued that a policy of liberal en block resection of adjacent organs and tissues may improve local control. A multicenter retrospective review of 382 RPS patients in France divided patients by surgical procedure into compartmental resection of contiguous organs (32%), resection of only involved organs (35%), simple complete resection (17%), and re-excision of tumor bed (6%).2 Incomplete gross resection (e.g., R2 resection) occurred in 65 of patients. Thirty-two percent of patients received radiation therapy and 37% received chemotherapy. The study found that compartmental resection of contiguous organs was associated on multivariate analysis with a 3.29-fold lower rate of local recurrence compared to only complete gross tumor resection. Morbidity occurred in 22% of patients, with about 5% of patients requiring reoperation and 3% dying of complications. In response to these Milan and French studies, an editorial to these studies argued that aggressive resection was predominately limited to the kidney, colon, and psoas that may be associated with less morbidity than resection of major vessels, and the pancreas or diaphragm that may also be involved by tumor.36 The editorial concluded: “Until better safety data and more convincing outcome data are available, we should not use the retrospective data from these studies, given the myriad of interpretative issues and the presence of various forms of bias, to change the surgical approach to patients with retroperitoneal sarcomas.”36

Bonvalot et al subsequently published a pooled series from two high-volume institutions.37 In the pooled data of 249 patients, 5-year overall survival was 65% and local recurrence-free survival was 78%. Further analysis demonstrated that resection of greater than three organs was associated with increasing morbidity, 12% of patients required reoperation postoperatively for complications, and 3% of patients suffered postoperative mortality. The authors again advocated for the use of aggressive surgical resection based on the high rate of complete resection and favorable recurrence and survival data. This article was accompanied by an editorial that again pointed out the possible flawed concept of resecting only selected contiguous organs and vital structures and the difficulty in interpreting retrospective analyses.38 Thus, there remains no consensus on the appropriate resection for RPS and no prospective trials to guide surgical practice. Certainly for surgeries requiring extensive organ resection or multiple surgeons from different specialties, the operation would ideally be treated at a high-volume sarcoma center. Of note, several articles on major vascular resections, liver resections, pancreaticoduodenctomies, and other aggressive strategies for primary RPS have been published.39–41

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree