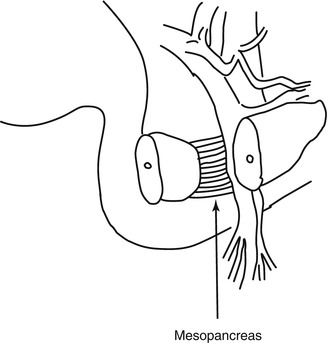

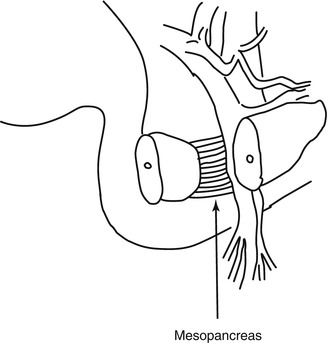

Fig. 16.1

The fusion fascia of the pancreatic head is called the “fusion fascia of Treitz” and that of the pancreatic body and tail is the “fusion fascia of Toldt.” Inf inferior (From reference Kimura [9])

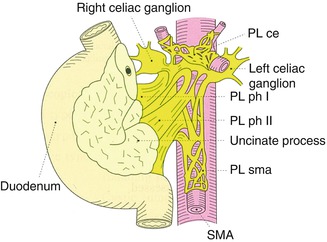

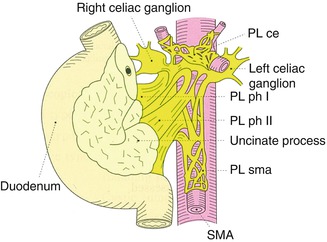

The concept of the nerve plexus around the pancreatic head was first reported by Yoshioka in 1958 [10]. The Japan Pancreas Society incorporated this concept and a corresponding diagram in the third version of the General Rules for the Study of Pancreatic Cancer in 1986 [11]. In this classification, the extrapancreatic nerve plexuses were categorized into seven groups: pancreatic head plexus I (PL ph I), pancreatic head plexus II (PL ph II), superior mesenteric arterial plexus (PL sma), common hepatic artery plexus (PL cha), plexus within the hepatoduodenal ligament (PL hdl), splenic plexus (PL sp), and celiac plexus (PL ce) (Fig. 16.2). After extrapancreatic nerve plexus invasion, particularly PL ph I and PL sma invasion, was found to have a correlation with patient prognosis and lymph node involvement along the superior mesenteric artery (SMA), it was adopted as a staging factor in the fifth edition of the General Rules for the Study of Pancreatic Cancer. However, the plexuses seemed to be exaggerated in this diagram because no dense nerve fibers had been shown in the previous anatomical report (Fig. 16.3) [12].

Fig. 16.2

The extrapancreatic nerve plexuses were categorized into seven groups according to the General Rules for the Study of Pancreatic Cancer. PL ph I pancreatic head plexus I, PL ph II pancreatic head plexus II, PL sma superior mesenteric arterial plexus, PL cha common hepatic artery plexus, PL hdl plexus within the hepatoduodenal ligament, PL sp. splenic plexus, PL ce celiac plexus (From reference Japan Pancreas Society [11])

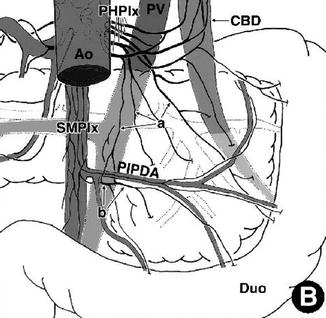

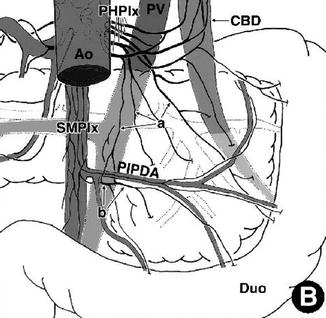

Fig. 16.3

Schema indicating the branches that originate from the posterior hepatic plexus (PHPlx) and superior mesenteric plexus (SMPlx) and spread on the deep surface of the head. (a) Twigs (twiglike nerves) independently running from the PHPlx to the pancreatic head. (b) Twigs originating from the SMPlx innervating the uncinated process. Ao aorta, CBD common bile duct, Duo duodenum, PIPDA posterior inferior pancreaticoduodenal artery, PV portal vein (From reference Yi et al. [12])

In 2007, Gockel et al. introduced the concept of the “mesopancreas” (Fig. 16.4) [13]. The mesopancreas is a retropancreatic structure extending from the back of the pancreatic head to the SMA, including the lymphatic system, vessels, and nerves, which corresponds to PL ph I and PL ph II according to the General Rules for the Study of Pancreatic Cancer [14]. Gockel and colleagues were the first to anatomically or surgically classify this structure. They advocated a complete resection of the mesopancreas to achieve curability of a pancreatic head tumor with direct or indirect invasion of the major vessels or regional lymph node metastasis.

Fig. 16.4

The mesopancreas strains itself dorsally of the mesenteric vessels as a whitish-firm, fatty tissue-like layer (From reference Gockel et al. [13])

16.3 Nerve Plexus Invasion by Pancreatic Cancer

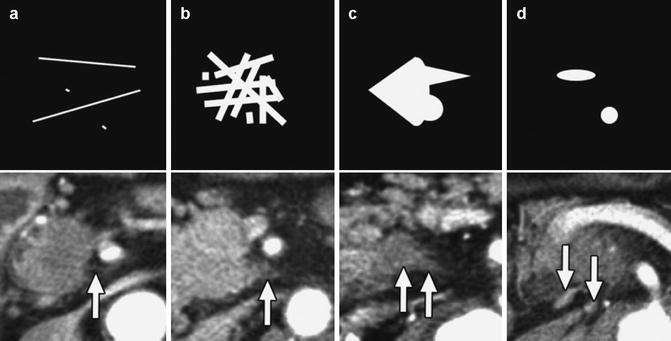

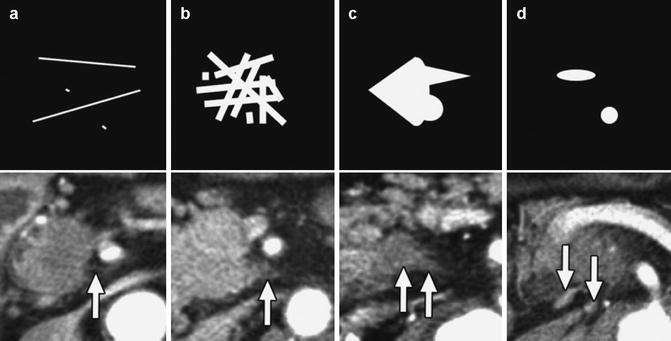

The pancreas is richly innervated by nerve fibers of the autonomic nervous system, and extrapancreatic nerve plexus invasion is known to be one of the most significant prognostic factors in patients with PDAC. Given the poor prognosis of patients with extrapancreatic nerve plexus invasion, preoperative diagnosis including multidetector computed tomography (MDCT) is crucial for staging and for treatment decision such as neoadjuvant therapy. Mochizuki et al. categorized four CT patterns of extrapancreatic nerve plexus invasion as follows (Fig. 16.5): (a) fine reticular and linear pattern (fine lines (less than 2 mm in diameter) and fine reticula (reticulation composed of fine reticular lines with abundant intermingled fat density)), (b) coarse reticular pattern (coarse reticula (reticulation also composed of reticular lines with less intermingled fat density)), (c) mass and strand pattern (over 2-mm diameter mass or strand-shaped soft tissue density connecting to the PDAC), and (d) nodular pattern (over 2-mm diameter isolated nodules) [15]. A point-by-point correlation between the MDCT findings and pathological specimens at the same section revealed that the (b) coarse reticular pattern and (c) mass and strand pattern reflected extrapancreatic nerve plexus invasion.

Fig. 16.5

Summaries of the four CT patterns. Top: schemas. Bottom: contrast-enhanced CT images corresponding to the respective schemas. (a) Fine reticular and linear pattern (arrow). (b) Coarse reticular pattern (arrow). (c) Mass and strand pattern (arrows). (d) Nodular pattern (arrows) (From reference Mochizuki et al. [15])

16.4 Pancreatic Cancer Surgery

Several randomized controlled trials and meta-analyses have concluded that prophylactic extended radical lymph node dissection does not contribute to improved survival after surgery [16–22]. Recently, Jang et al. compared standard pancreatoduodenectomy including dissection of proximal lymph nodes with extended pancreatoduodenectomy with extensive dissection of lymph nodes and the right half of the nerve plexus around the superior mesenteric artery (SMA). Their study revealed no significant differences in overall survival [22].

On the other hand, outcomes related to the resection margin have been controversial. Several authors have reported that a positive resection margin is a poor prognostic indicator, whereas other studies have failed to demonstrate a difference [23–29]. In 2012, Konstantinidis et al. proposed a “true” R0 resection (no evidence of malignancy in any of the resection margin) and showed that patients with R0 resections had a favorable survival compared with those with R1 resections (23 vs. 14 months; P < 0.001). However, survival after resections of 1-mm margin or less (R0-close) was similar to that of R1 resections; both groups had a significantly shorter median survival than patients with a margin of greater than 1 mm (R0-wide) (16 vs. 14 vs. 35 months in the R0-close, R1, and R0-wide groups, respectively; P < 0.001) [30]. They concluded that R0 resections have an improved survival compared with R1 resections but that this survival benefit is lost when the tumor is within 1 mm of the resection margin. It remains unclear whether small differences in the procedures contribute to patient survival after surgery because PDAC is extremely malignant; however, the procedure should be completed if the invasiveness of the procedure is acceptable to the patient.

To date, whether the complete resection of the mesopancreas is involved in disease recurrence and patient survival after surgery for pancreatic head cancer remains unclear. However, the mesopancreas was reported to be the most frequent site of R1 resections [31]; therefore, total excision of the mesopancreas and complete circumferential lymphadenectomy have recently been considered to be key points in curative surgery, as described by several authors [31–34].

Nerve plexus invasion frequently spreads toward the dorsal side of the PL sma (Fig. 16.6) [35]. PDAC abutting the SMA not exceeding 180 degrees of the circumference of the vessel wall is defined as “borderline resectable” disease; however, up-front surgery for this condition is highly controversial. We compared between patients who underwent up-front surgery and patients who underwent neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy (NACRT) followed by surgery [36]. The rate of curative resection was statistically similar. The results of the propensity score weighted logistic regressions indicated that the incidences of pathological lymph node metastasis and a pathological positive resection margin were significantly lower in the NACRT group (odds ratio, 0.006; P < 0.001 and odds ratio, 0.007; P < 0.001, respectively). Among the propensity score-matched patients, the estimated 1- and 2-year survival rates in the NACRT group were significantly longer than those in the up-front surgery group. Therefore, we concluded that NACRT, rather than up-front surgery, provided short-term clinical benefits and better survival in patients with PDAC in contact with the major arteries (Fig. 16.7) [36].

Fig. 16.6

(a) Photograph of the resected specimen with PL ph II invasion. (a) CT scan image corresponding to A. The carcinoma spread from the left side of lower uncinate process along the inferior pancreaticoduodenal artery, continued behind the SMA, and finally extended to the left side of the SMA. Red, yellow, green, and blue enclosures on the photograph indicate the area of the primary tumor, extrapancreatic nerve plexus invasion, lymph node metastasis, and retropancreatic tissue invasion, respectively. Red arrowheads on the CT scan image indicate the primary tumor. CBD indicates the common bile duct, WD Wirsung duct, IPDA inferior pancreaticoduodenal artery (From reference Makino et al. [35])

Fig. 16.7

(a) Kaplan–Meier curves for disease-specific survival after the initiation of treatment for unmatched patients who underwent up-front surgery (N = 71) or neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy (NACRT) (N = 21; P = 0.001). The median survival times in the up-front surgery and NACRT groups were 13.1 and 29.1 months, respectively. (b) Kaplan–Meier survival curves for the propensity score-matched upfront surgery (N = 17) and NACRT (N = 17) groups (P = 0.007). In the upfront surgery group, the median survival time was 13.9 months, and the estimated 1- and 2-year survival rates were 66.7% and 16.0%, respectively. In the NACRT group, the median survival time could not be calculated because the survival curve did not reach the 50% line before the end of the study, and the estimated 1- and 2-year survival rates were 80.0% and 65.2%, respectively (From reference Fujii et al. [36])

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree