Fig. 1

Algorithm for management of transplantable hepatocellular carcinoma at Henri Mondor Hospital, Creteil, France [3]

For patients with a solitary HCC<5 cm, no evidence of extrahepatic tumor burden, compensated liver disease, and the absence of significant portal hypertension, resection can be performed with reduced mortality and morbidity over open resection in selected cirrhotic patients, and is associated with excellent overall survival. It is under these circumstances we argue laparoscopy to have an important role.

3 Indications for Laparoscopic Resection

Indications for laparoscopic hepatectomy do not differ from those of open surgery. After the prerequisite evaluation of liver function and portal hypertension, technical feasibility is the limiting factor [30–35]. In open surgery, only Child-Pugh A patients with a future liver remnant volume over 40 % are typically considered for resection in cirrhotic patients with HCC. Upper endoscopy, platelet count, gross spleen size, collateral circulation on cross-sectional imaging, and venous pressure gradient when available are evaluated as indicators of portal hypertension. Presence of portal hypertension is not an absolute contraindication, but indications have to be cautiously balanced with risks, and a limited resection is typically favored [36, 37]. The same criteria should generally be adopted for laparoscopic liver resection.

In order to select patients technically amenable to the laparoscopic approach, two criteria have been considered by all authors, tumor location and tumor size. Anatomical resection or a wide margin is required for appropriate resection of HCC. The choice of a laparoscopic approach should not compromise this principle. Wedge resection, segmentectomy, or left lateral sectionectomy (Figs. 2 and 3) of HCC located in segments 2–6, are the best indications for the laparoscopic approach [30, 31, 38]. These segments have been coined the laparoscopic segments, because their anterolateral position allows for excellent visualization and mobilization during the surgical procedure (Fig. 4). Segments 7, 8, and 1 are difficult to visualize laparoscopically and may require extensive mobilization of the liver prior to resection. However, Cho and colleagues have reported on a series of 36 patients with lesions located in segments 7, 8, and 4a treated by pure laparoscopy, of which 70 % underwent anatomic segmentectomies, atypical resections and right posterior sectionectomies [34, 39]. Laparoscopic resection of segment 1 lesions, and right or left hepatectomies have also been performed [32, 40]. The role of laparoscopy for lesions in segments 7, 8, and 1 and major resections have not yet been codified, and further studies are necessary to confirm the reproducibility of these procedures. The risk of bleeding and biliary injury is higher and major laparoscopic resections should only be considered in lesions remotely located from the hilum and the main hepatic veins. Except for exophytic lesions which are easy to resect by laparoscopy even if large in size, laparoscopy is usually not recommended for HCC exceeding 5 cm in diameter because of difficult tumor mobilization, and risks of rupture or inadequate margins [30, 34, 41–45].

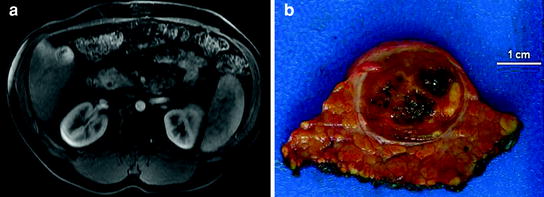

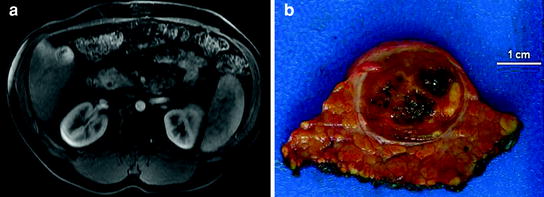

Fig. 2

Superficial 2 × 2.5 cm hepatocellular carcinoma at intersection of Segments 5 and 6 resected laparoscopically. a Preoperative MRI; b Inked pathology specimen showing sufficient margins

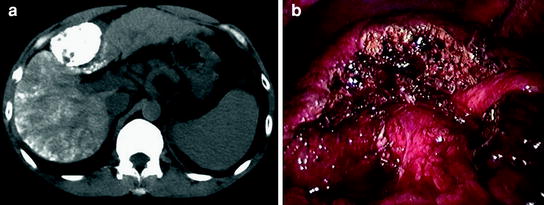

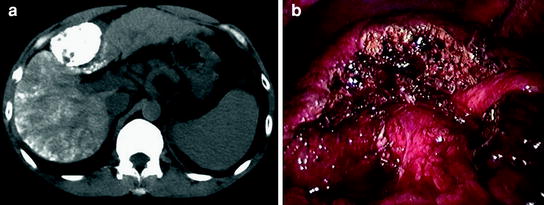

Fig. 3

Segment 4b hepatocellular carcinoma in patient with cirrhosis. a Preoperative CT; b Haemostatic cut-surface after laparoscopic segmentectomy. Note the hilar structures inferiorly at 6 o’clock and the ligamentum teres at 3 o’clock

Fig. 4

Segments 2, 3, 4a, 5, and 6 are most amenable to laparoscopic resection

Importantly, all patients should be discussed at a multidisciplinary conference attended by surgeons, hepatologists, diagnostic radiologists and interventional radiologists, and an individual treatment plan is determined by consensus. High quality magnetic resonance imaging or multi-detector triple-phase computed tomography is mandatory for surgical planning.

4 Laparoscopic Resection: General Benefits

Laparoscopic partial hepatectomy provides many of the benefits that laparoscopy has offered to patients undergoing other abdominal operations. Non-randomized studies have demonstrated shorter operative times, (although this has not been our experience) [32, 33, 43], shorter lengths of hospitalization [32, 33, 40, 46], less operative blood loss [32, 33, 43, 47], less transfusion requirements [32, 33, 43], less analgesic requirements, [46] quicker return to oral consumption [46], less morbidity [32, 33, 43], and less postoperative adhesions [48, 49]. Studies have demonstrated decreased costs when accounting for shorter operative times and hospitalizations [33, 50].

The mortality and morbidity rates in these studies are at least equivalent if not better than those of large case series of open liver resections. In their review of 127 published papers on laparoscopic hepatic resection, Nguyen and colleagues (2010) found a cumulative mortality rate of 0.3 % [51]. This compares favorably to the 0–5.4 % reported in the open resection literature from high volume centers. All deaths were postoperative, and most often caused by liver and multi-organ system failure. Of 2,804 patients, a total of 295 complications were reported (10.5 %), with a range of 0–50 % across the 127 studies. Liver-specific complications were rare and included bile leaks (1.5 %), transient liver failure/ascites (1 %), and abscess (2 %). The remaining 6 % of complications were those common to all operations, including but not limited to hemorrhage, wound infection, hernia, bowel injury, arrhythmia, and urinary or respiratory tract infections.

Barriers to the wide acceptance of laparoscopic surgery such as threat of gas embolism and significant risk of bleeding have not been evidenced in the literature [52]. Gas embolism is rarely reported and is usually without any clinical consequences, except for transient cardiovascular alterations. Hemorrhagic complications can occur during parenchymal transection and are mainly related to hepatic vein injuries [30, 31, 43, 53]. These have been managed either laparoscopically or by conversion to laparotomy, rarely with serious consequences. In general, similar conversion rates, in the range of 5–15 %, have been reported whether for HCC or other lesions [39, 42, 44, 46, 54–58]. The reasons for conversion are essentially three: bleeding, failure to progress (technical), and oncologic.

Studies have consistently demonstrated that operative safety and postoperative morbidity improve with experience [43, 51].When comparing our early and late groups, we found statistically significant reductions in operative time (210–150 min), blood loss (300–200 ml), conversion to laparotomy (16.9–2.4 %), and morbidity (17.2–3.4 %) [54].

5 Laparoscopic Resection in Patients with Cirrhosis

In cirrhotic patients, even minor liver resections can carry a high risk of complications and death. Across the more than 2000 published laparoscopic liver resections, 10 postoperative deaths have been reported (<0.5 %) [30, 31, 33, 34, 40, 41]. Importantly, 60 % occurred in cirrhotic patients [30, 31, 33, 41]. Buell et al. recently reported more than 250 laparoscopic liver resections and observed significantly increased mortality in cirrhotic patients compared with noncirrhotic (9.7 % vs. 0.3 %) [33]. These data reinforce that liver surgery in cirrhotic patients carries a higher risk, even if performed laparoscopically. Short-term results in series including more than 10 laparoscopic liver resections for HCC are detailed in Table 1.

Table 1

Morbidity and mortality following laparoscopic liver resection in patients specifically affected by HCC: series including more than 10 patients

Author | N | Major hepatectomy | Mortality | Morbidity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Belli [81] | 23 | 0 % | 4 % (1) | 22 % (5) |

Buell [33] | 36 | 9.7 % (3/31)a | 9.7 % (3/31)a | 29 % (9/31)a |

Cai [46] | 24 | NR | 0 % | 0 % |

Chen [59] | 116 | 3 % (4) | 0 % | 6 % (7) |

Cherqui [54] | 69 | 7 % (5) | 0 % | 22 % (15) |

Cho [34] | 57 | 18 % (10) | 0 % | 16 % (9) |

Dagher [57] | 32 | 13 % (4) | 3 % (1) | 25 % (8) |

Huang [60] | 27 | NR | 0 % | 19 % (5) |

Inagaki [61] | 36 | 0 % | 0 % | NR |

Kaneko [56] | 30 | 0 % | 0 % | 10 % (3) |

Lai [62] | 25 | 4 % (1) | 0 % | 16 % (4) |

Santambrogio [55] | 19 | 0 % | 0 % | 11 % (2) |

Sasaki [44] | 37 | 0 % | 0 % | 3 % (1) |

Shimada [45] | 17 | 0 % | 0 % | 6 % (1) |

Teramoto [63] | 11 | 0 % | 0 % | 18 % (2) |

Vibert [31] | 16 | NR | 6 % (1) | NR |

Multiple small case–control studies and series demonstrating lower morbidity and improved recovery when compared with open resection have been published [41, 44, 56–58, 64]. Laparoscopy for resection of HCC has been used most often in Child-Pugh A cirrhotics, and in a limited number classified as Child-Pugh B or C. The latter group has typically involved atypical resections of very peripheral or pedunculated tumors. Nearly 40 % of the Henri Mondor overall laparoscopic experience has been in patients with chronic liver disease. And of those performed for malignancy, 63 % have been performed for HCC, all in the setting of chronic liver disease.

In the literature, morbidity rates after laparoscopic liver surgery range from 5 to 20 % [30, 33, 34, 40, 42–44, 65–68]; considering cirrhotic patients they tended to be higher (Table 1) [33, 34, 42, 45, 46, 54, 56, 57, 59, 60, 62, 63]. In the above-mentioned series of Buell et al. morbidity was 29 % in cirrhotics versus 14 % in noncirrhotics (p = 0.02) [33]. In our series of 174 laparoscopic resections, mortality was nil and morbidity occurred in 14.4 % of cases. Considering the 69 patients affected by HCC, the morbidity rate was 21.7 %, but it significantly decreased to 10 % in the second half of our experience [54].

Tranchart and colleagues (2010) recently compared 42 laparoscopic and 42 open resections for HCC from the same time period [64]. There were no significant differences in tumor size, Child-Pugh, presence of cirrhosis, or types of resection performed. The mean duration of surgery was similar in the two groups, and the mean hospital stay was significantly shorter in the laparoscopic group (6.7 vs. 9.6 days; p < 0.0001). Significantly less bleeding was observed in the laparoscopic group (364.3 vs. 723.7 ml; p < 0.0001). Postoperative ascites was less frequent after laparoscopic resections (7.1 vs. 26.1 %; p = 0.03). General morbidity was similar in the two groups (9.5 vs. 11.9 %; p = 1.00).

In the largest series of laparoscopic HCC resections by Chen and colleagues (2008), laparoscopic resection of <1 segment (Group 1; n = 97) were compared with resections of 2 or more segments (Group 2; n = 19) [59]. With the exception of a greater number of Child-Pugh B & C patients in Group 1 (20 % vs. 0 %), there were no significant difference between the two groups. In both groups, patients resumed full diet on postoperative days 2–3 and the average hospitalization was 6 days. The operative time was 152.4 ± 336.3 min and 175.8 ± 57.4 min in Groups 1 and 2, respectively. Blood loss was significantly different in Groups 1 and 2 101.6 ± 324.4 ml and 329.2 ± 338.0 ml, respectively. Similar to the study by Tranchart and colleagues (2010), the laparoscopic group required less blood transfusions, but in both studies this was not a significant finding [64]. Mortality was nil, and morbidity occurred in 6.2 % and 5.2 % of Groups I and II, respectively.

In another large, single-institution series, Yoon and associates (2010) compared outcomes for treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma in segments 2–6 (Group 1; n = 44) versus segments 1, 4a, 7, and 8 (Group 2; n = 25) [69]. There were no statistically important clinical or pathologic differences between the two groups including presence of cirrhosis and Child-Pugh scores. Group 2 had longer operative times (p = 0.001), longer postoperative stays (p = 0.04), and a tendency toward a higher rate of conversion to laparotomy (p = 0.054) and blood loss (p = 0.068). Despite this, there was no significant difference between the two groups regarding morbidity (p = 0.375), and there were no mortalities. In total, 15 patients (21.7 %) experienced 19 postoperative complications. Atypical resections were more often performed in Group 1, whereas Group 2 more often required larger anatomical resections of >2 segments. This complexity likely explains the differences between these groups and further illustrates that the posterolateral segments are not as easily amenable to laparoscopy.

The laparoscopic approach decreases the rate of postoperative ascites. Possible explanations include less intraoperative mobilization, the preservation of venous and lymphatic collateral pathways in the abdominal wall and improved re-absorption of ascites, and reduced need for intraoperative volume loading [35, 41, 47, 52, 70–72].

As a consequence of decreased adhesions formed after an initial laparoscopic versus open resection, reoperations such as repeat hepatectomy and liver transplantation can often be performed more easily, with less blood loss, fewer transfusion requirements, and reduced operative time [43, 49, 50]. This counters the original criticism put forth by Adam et al. in their report of poor outcomes following salvage liver transplantation after previous open hepatectomy because of adhesions related to primary treatment and increased blood loss [28]. In our study comparing patients who had undergone a previous open or laparoscopic liver resection, the absence of adhesions at the time of liver transplantation in the laparoscopic group allowed for hepatectomy in a mean of 150 ± 52 min, versus 247 ± 71 in the open group. Additionally, the median number of units transfused during the hepatectomy in the open group was 2, versus 0 in the laparoscopic group [48]. These are significant benefits given the harmful immune and oncologic impact of blood transfusion. Transfusion rates have been identified as independent prognostic factors for disease-free survival in HCC and blood loss during surgery was recently shown to be associated with recurrence and survival rates after resection for HCC. Reduced adhesions after laparoscopic liver surgery have been confirmed by Belli et al. in their analysis of redo surgery [49].

These studies demonstrate the safety and benefits of laparoscopic resection of HCC in compensated cirrhotics. Although no randomized studies have been performed, there is strong support that laparoscopic resection in selected patients and lesions are less harmful to the patient than open resection in the multidisciplinary management of HCC.

6 Oncologic Outcomes

Controversy about laparoscopy in cancer patients arose from unacceptable peritoneal and port site seeding in early patients with incidental gallbladder cancers or with colon cancer [73, 74]. Proper use of oncological surgical principles has reduced this problem to the point that there are no more differences as compared to open surgery. It is highly important that oncological principles are strictly followed: “no touch”, no direct manipulation of the tumor, immediate conversion in case of locally advanced cancer, and protection for extraction.

With regard to margins, recurrence, and survival, comparable results between open and laparoscopic resections for HCC have been well demonstrated in the literature [3, 51, 52, 75]. With a median over 1 cm in almost all series and few R1 resections being reported, acceptable surgical margins are achieved with laparoscopy [33, 34, 42, 43, 45, 46, 57, 59, 63]. Table 2 provides reported overall survival and disease-free survival from 10 published studies chosen because they either contained more than 25 patients or utilized a case-matched design. Resection margins are also presented. In none of the case-match studies was there a statistically significant difference in overall survival or disease-free survival between the two groups. All studies contained >55 % of patients with histologically confirmed cirrhosis, with the exception of Kaneko et al. (51 %) and Sarpel et al. (45 %) [56, 75]. These outcomes are similar or even better than those reported in open series [24, 76, 77]. No port site recurrences have been reported.

Table 2

Laparoscopic hepatectomy for hepatocellular carcinoma: margins, overall survival, and disease-free survival in case–control studies and series with over 25 patients

Author

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|

|---|