been described [9]. Other less common syndromes first seen as primary hypogonadotropic hypogonadism include Prader-Willi syndrome and Laurence-Moon-Biedel syndrome.

frequency of this disorder is variable, depending on ethnic origin. Presentation may be at birth with ambiguous genitalia, or it may be delayed until later in life, particularly in the non—salt-wasting variety. In childhood, accelerated growth and bone maturation and signs of hyperandrogenism (hirsutism, acne, increased musculature, alopecia) appear. If untreated, amenorrhea and short final adult stature are found (because of early closure of the epiphyses secondary to androgenic stimulation). The diagnosis is made with the finding of elevated 17-OH progesterone, either in the basal state or with adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) stimulation. Genetic testing will confirm the presence of a variety of mutations of the CYP21 gene on chromosome 6 [12]. Treatment consists of glucocorticoid replacement to suppress excess ACTH and hence adrenal androgen production, with care to avoid excess glucocorticoid, which can cause growth retardation, osteopenia, and iatrogenic Cushing disease [13, 14].

defects (e.g., bicuspid aortic valve and coarctation of the aorta), and 30% have renal anomalies. The risk of death from aortic aneurysm is high (relative risk [RR] of 63.23, with a 95% confidence interval [CI] of 20.48-147.31), and an initial evaluation with periodic echocardiography and follow-up by a cardiologist are needed [18]. Thyroid disease, usually Hashimoto disease, may occur in up to 30% of affected patients; therefore, TSH levels should be measured every 1 to 2 years or if symptoms suggestive of thyroid disease develop. Short stature can be improved significantly with the early use of growth hormone, and consideration for use should be given if and when the height is less than the 5th percentile or as indicated based on specific clinical features [13, 19]. Estrogen use will cause fusion of the epiphyses and may therefore limit final adult height (AH), depending on the total length of growth hormone therapy before starting estrogen [20]. However, starting growth hormone early may allow the use of estrogen at age 12 or 13 without compromising height gain [21]. Early use of estrogen may have some benefit on motor and nonverbal function in girls with TS [22], although this must be reconciled with the goal of increasing height. Bone-density studies should be done in adults and periodically thereafter [17]. Patients with TS, particularly primarily those with mosaicism, may rarely conceive spontaneously, though the outcomes of pregnancy often include chromosomal abnormalities, congenital anomalies, and fetal loss [23, 24]. The potential for pregnancy does not improve with medical interventions [25]. Ovum donation has allowed successful pregnancy outcomes in many women with Turner syndrome, but it is critical to detect somatic abnormalities, particularly cardiac disease, before embarking on a course of assisted fertility. Cyclic hormone replacement therapy (HRT) is justified by recent studies that suggest a beneficial effect of estrogen therapy on bone density and fracture risk in such patients [26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31].

male pattern distribution (hirsutism), acne, or hair loss (alopecia). However, the finding of hyperandrogenism does not define excess androgen production but can be a significant indicator of the presence of an androgen excess disorder, leading to the measurement of testosterone and other androgens, evaluating if there is an overproduction by the ovaries or adrenal glands. Hirsutism may occur without actual elevation in androgen levels if increased target organ sensitivity to androgen action exists. It should be noted that ethnic differences in the number of hair follicles present and individual skin sensitivity of the pilosebaceous unit to androgens are major determinants of the presence of hirsutism, as well as acne and androgenic alopecia [38].

Table 5.1. Amenorrhea Summary | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

(31%—35%) and type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM) (7.5%—10%) [47]. With 50% to 70% of all women with PCOS having some degree of insulin resistance [48], a hypothesis to explain these aspects of PCOS therefore follows that this metabolic disorder of compensatory hyperinsulinemia exerts adverse effects on the hypothalamus, pituitary, ovaries, and, possibly, adrenal glands, explaining the oligomenorrhea and hyperandrogenemia.

Glucose intolerance/diabetes

Elevated blood pressure level (≥130/85)

Increased waist circumference (≥35 inches or waist-to-hip)

Reduced high-density lipoprotein cholesterol level (≤50 mg/dl)

Elevated triglyceride levels (≥150 mg/dl)

Manage hyperandrogenism through reduced androgen production and blockage of androgen action

Improve reproductive function

Control of menstrual disorders

Ovulation induction

Ameliorate complications putatively due to insulin resistance

Glucose intolerance

Dyslipidemia

Hypertension

Atherogenesis

Weight management

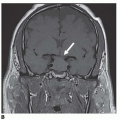

of GnRH secretion. Discontinuation after exposure to exogenous sex steroids may also result in activation of the central axis, resulting in acquired CPP. MRI of the brain and hypothalamopituitary region should be done, as well as a bone-age test.

and sex hormone levels in the pubertal range with limited predicted adult height (PAH) (<5th percentile) or significant psychosocial problems from menses or early development [80]. Generally, therapy is initiated in very young children to prevent sexual development and in older children when bone-maturation acceleration outpaces linear growth velocity, resulting in premature closure of the epiphyses and diminished final AH. No studies document the benefits of gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH) therapy on ultimate psychosocial well-being in children with this disorder. Quality-of-life issues should enter into therapy considerations but must be individualized and have not been well studied. Long-term safety issues pertaining to the use of GnRH agonists are largely unknown. A review of earlier trials of GnRHa use suggests that therapy should be started before age 8 years to have a significant impact [79]. Therapy with GnRHa generally produces a height increase of 3 to 8 cm over that in untreated patients but typically 1 to 7 cm below the normal PAH. Newer studies suggest that a final AH appropriate for midparental height prediction is achieved by 85% to 90% of patients. Although some studies suggest that weight gain may be associated with therapy with GnRH analogues [81, 82], two recent large trials of GnRH therapy in 121 girls over 1 year revealed that GnRH therapy did not reverse the accretion of bone mass nor did obesity occur. Body composition and later menstrual function were normal and progression to PCOS was not observed [83, 84].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree