Rehabilitation of Swallowing and Speech in Patients Treated for Cancer of the Head and Neck

Jan S. Lewin

INTRODUCTION

Unlike past decades in which functional rehabilitation of speech and swallowing was often considered an afterthought once definitive treatment of the head and neck cancer was completed, functional preservation, that is, the ability to eat, drink, and speak normally, shares a primary goal with cure and survival in the contemporary management of patients with cancer of the head and neck. Patients who were once satisfied if not grateful to be cured of their cancer, whether or not they could eat or speak, currently expect that verbal communication and the ability to swallow without aspirating will remain intact after treatment, with a spontaneous ability to return to a normal daily routine once they have recovered from treatment. Unfortunately, as organ-sparing treatment alternatives for head and neck cancer have intensified, and their ability to cure the disease has improved, the short and long-term effects on speech and swallowing have become even more severe. Treatment regimens have become stronger, frequently combining surgical and nonsurgical alternatives, given in regimens and doses that often result in significant anatomical defects, severe fibrosis, and long-term neuropathies that can cause irreversible damage to the upper aerodigestive tract (UADT), that in some instances, relegate the patient to a tracheostomy and gastrostomy tube dependence.

The diagnosis of cancer of the head and neck, the tumor itself, and the consequences of its treatment can impart a tremendous impact on the individual’s physical, physiologic, psychological, and social functioning. The diagnosis itself will almost certainly be associated with concerns regarding body image, self-concept, self-esteem, and the ability to return to work and social interactions. However, in all cases, cancers of the head and neck will, to some degree, affect speech and swallowing function that will require accurate evaluation and targeted rehabilitation from clinicians with critical expertise and experience managing patients with cancer of the head and neck. Pretreatment evaluation and counseling and posttreatment intervention must be timely and precise to optimize patient outcomes and successful recovery. Hence, treatment based on limited knowledge and inaccurate interpretation of evaluations remains ineffective and useless.

Over the past two decades, there has been a paradigm shift away from ablative surgery to organ preservation with an associated emphasis on quality of life, function, and the cost of treatment. For patients with early cancer of the larynx, the treatment dichotomy generally remains a decision to use laser excision of the cancer or to treat with radiation therapy. For patients with advanced cancer of the larynx, the contemporary focus is also to preserve the larynx. Unfortunately, elevated rates of speech and swallowing dysfunction prevail. Hence, in some cases, questions have arisen as to the true benefit of organ preservation versus total organ resection using contemporary surgical-prosthetic methods of voice restoration and early swallowing exercise regimens to maintain acceptable oral communication and prevent long-term dysphagia.

Likewise, for patients with cancer of the oropharynx, the question regarding the optimal treatment alternative also continues to be investigated and debated. Today’s patient with cancer of the oropharynx is generally younger than his or her older counterpart, often in the fourth or fifth decade of life, with a better prognosis for survival, and is adamant about the ability to return to a normal routine of work and social activities after treatment. Thus, posttreatment morbidity and function have become primary considerations in decisions regarding the contemporary treatment of cancer of the oropharynx. Despite ongoing investigation, the clear advantage of new endoscopic surgeries (eHNSs) of the head and neck using laser and robotic resections versus nonsurgical alternatives that use intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) with photon or proton beams, or adaptive radiation protocols, to preserve function, is still being investigated.

What we have learned over the past several decades is that patients’ goals have not changed significantly; their posttreatment expectations continue to be able to eat and swallow by mouth, to speak using their natural laryngeal voice, and to keep their appearance unchanged. Patients’ self-perception of their ability to eat and drink is often inaccurate and incongruous with the findings seen on instrumental tests; that is, what is seen on objective examination does not always corroborate the patients report. Experience and investigation have demonstrated that in patients who have been treated with radiation therapy, severe dysfunction, primarily dysphagia, often occurs late, years after the cancer treatment has ended, and is most often refractory to current standard methods of behavioral dysphagia therapy. Likewise, high rates of aspiration that are often silent (without patient awareness) and result in aspiration pneumonia and chronic gastrostomy tube dependence remain common occurrences and are also associated with elevated rates of dysphonia and vocal fold paralysis particularly after surgical treatment for cancers of the head and neck. Finally, data demonstrate that anatomical preservation

does not ensure functional preservation nor is the potential for recovery a guarantee for successful functional results. Likewise, outcomes will vary in terms of both the response to the cancer treatment as well as the long-term speech and swallowing results. Thus, the exact predictors of functional outcomes still remain unknown.

does not ensure functional preservation nor is the potential for recovery a guarantee for successful functional results. Likewise, outcomes will vary in terms of both the response to the cancer treatment as well as the long-term speech and swallowing results. Thus, the exact predictors of functional outcomes still remain unknown.

Normal Speech and Swallowing Function

Speech and swallowing are highly complex processes that depend on a series of neuromuscular events that rely on rapid, highly coordinated, and precisely executed movement. The sequence of the motor events involved in both speech and swallowing is fairly predictable, although in the case of swallowing, investigators have shown that the relative timing of these events varies, depending on the size and consistency of the bolus of food or liquid being swallowed.1,2,3 In general, speech production is affected primarily by cancers that involve the oral tongue or other structures of the oral cavity, whereas swallowing can be affected by any cancer within the aerodigestive tract. However, in most instances, the greatest impact on swallowing occurs from tumors that affect the base of the tongue or pharynx.4

Speech production and intelligibility depend on precise sequences of movement and contact by the articulators of the oral cavity, mainly the lips, tongue, and soft palate, that rapidly change the configuration of the vocal tract. Although articulation is the main contributor to speech intelligibility, speech understandability is also influenced by voice quality and resonance. Hence, any cancer that affects structures other than the tongue, such as those that impact the larynx, specifically vocal fold function, or fill the recesses of the naso-, oro-, or laryngopharynx, will result in changes in the quality of the voice (loudness, pitch, resonance) and also indirectly influence speech intelligibility. The place of articulatory contact may be bilabial (m, p, and b) or it may be velar (k and g). Whether the sound is nasal or voiced depends on the valving action from the velum, which requires a lowering of the soft palate for nasal sounds (m, n, and ng) or valving from the larynx that involves the opening or closing of the vocal folds to produce the voiced distinction between various sounds (p and b, t and d, k and g). In the case of vowels, the shape and height of the tongue are the key determinants of sound distinction. Thus, a cancer that involves the oral cavity, pharynx, or larynx will have some effect on speech and voice production and ultimately on conversational intelligibility.

The act of swallowing can be divided into four unique stages, the oral preparatory, oral, pharyngeal, and esophageal phases that involve more than 30 pairs of muscles and six cranial nerves. Each of these stages depends on intact neurologic function and anatomy with the triggering of each successive stage dependent on the timely occurrence of the previous one. Variations in normal anatomy that affect size, shape, or symmetry have little significant impact on swallowing in healthy individuals but may result in impaired swallowing or further decompensation including aspiration in an otherwise debilitated patient.5 In general, the oropharyngeal swallow begins at the lips and ends as the bolus enters the cervical esophagus at the level of the cricopharyngeal inlet and involves both voluntary and involuntary control mechanisms, and the entire oropharyngeal swallow should take no longer than 1 to 2 seconds in normal individuals.6 Only the oral preparatory, oral, and pharyngeal stages can be addressed by behavioral therapies, as the esophagus is a relatively less complex muscular tube, for which the main therapeutic maneuver is dilation. Although the gastrointestinal radiologist and the speech pathologist work together to diagnose abnormalities associated with swallowing function, diagnosis of abnormalities associated with the esophageal stage of swallowing remains the responsibility of the diagnostic radiologist.

Risk and Predictors of Dysfunction

Tumor site and extent and treatment intensity are the key clinical predictors of functional outcomes after organ preservation.7 Data demonstrate that among cancer sites treated with radiation or chemoradiation regimens, cancers of the hypopharynx portend the worst functional outcomes. Both cancer of the hypopharynx and combined regimens of chemotherapy and radiation are associated with the highest rates of swallowing-related dysfunction including dysphagia, stricture, and pneumonia when compared to other cancer sites such as the tongue, larynx, and oropharynx or single-modality treatments or a combination of surgery and radiation therapy.8 Although data suggest that the staging of the primary cancer of the head and neck carries a prognostic significance per TNM criteria, T stage appears to be the most consistent staging variable that impacts long-term function, often predicting the severity of dysphagia, gastrostomy dependence, and aspiration after treatment of cancer of the head and neck. Oropharyngeal primary cancers have the second highest risk of dysphagia after treatment. A 39% to 64% prevalence of long-term dysphagia has been documented in patients with cancer of the head and neck treated with combined regimens of chemotherapy and radiation.8,9

Changes in voice remain the primary complaint in more than 75% of patients treated for early laryngeal disease (T1-T2) regardless of the treatment modality, and although subjective reports of long-term vocal outcomes are generally comparable, better acoustic and perceptual measurements have been reported in patients treated with radiation therapy.10 Swallowing is generally not a complaint of patients treated for early cancer with a similar reported quality of life for both groups. However, the increased financial impact for patients treated with radiation therapy and the patient burden of missed work hours, travel time and distance, and the number of hours associated with treatment delivery are often concerns of patients selected to receive radiation therapy, in favor of surgical alternatives such as endoscopic laser procedures.

For patients with early cancer of the larynx who have been treated with radiation therapy, a continued history of smoking after completion of treatment has been shown to be associated with lower fundamental frequency changes in the voice and poorer vocal quality when compared with results in nonsmokers.11 Cancers that affect the anterior commissure generally result in patient complaints related to weak, breathy vocal quality and problems with pitch variation similar to the complaints of patients who have received larger volumes and doses of radiation (>60 Gy).12 In contrast, superficial cancers of the true vocal folds have been shown to result in better vocal outcomes after laser resection than do cancers that are deeply invasive into the muscle of the true vocal fold. Large bulky cancers that invade the vocal fold or involve the anterior commissure put the patient at risk for poor vocal quality

that is often weak in intensity and breathy in quality because of the large postoperative glottic defect that results in glottic incompetency for voice production. Unfortunately, there are few options for vocal improvement, behavioral or surgical, in these instances, and practice has shown that patients often experience better vocal outcomes after radiation therapy in lieu of a large defect that limits the ability to compensate or restore the voice after resection. Our anecdotal experience suggests that most patients still remain more willing to accept a poor voice in favor of the decreased patient burden associated with laser resection.

that is often weak in intensity and breathy in quality because of the large postoperative glottic defect that results in glottic incompetency for voice production. Unfortunately, there are few options for vocal improvement, behavioral or surgical, in these instances, and practice has shown that patients often experience better vocal outcomes after radiation therapy in lieu of a large defect that limits the ability to compensate or restore the voice after resection. Our anecdotal experience suggests that most patients still remain more willing to accept a poor voice in favor of the decreased patient burden associated with laser resection.

Alternatively, patients with advanced (T3-T4) cancer will experience greater and more severe functional debilitation particularly after organ preservation. More than 90% of patients will complain of dysphonia, of which ˜25% will report severe vocal disabilities. Up to 10% mortality rates associated with aspiration pneumonia have been reported in treated patients with advanced cancers of the head and neck.13 Late-occurring dysphagia and aspiration remain common with reported rates of silent aspiration as high as 70% in patients who aspirate14,15 and rates of percutaneous gastrostomy (PEG) tube placement between 70% and 80% with long-term dependence >12 months between 5% and 15%.7 Unfortunately, early recovery of swallowing may be misleading because of the delayed fibrosis and neuropathy that can eventually result in laryngopharyngeal dysfunction inhibiting the ability to swallow by mouth.

The cancer-related risk factors for long-term swallowing dysfunction generally have included advanced T stage, primary cancers that involve more than 50% of the base of tongue,9,16,17 cancers that involve the tonsil and extend to the pharyngeal wall, and cancers with advanced cervical lymph node metastases. Patients who are nutritionally compromised and who demonstrate pretreatment changes in diet, G-tube placement, weight loss, or malnutrition are at significant risk for long-term dysphagia. In addition, patients with persistent or recurrent cancer who require salvage procedures such as surgery or who present with comorbid diseases such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), diabetes, neuromuscular degenerative disease, substance abuse, or continued smoking, among others, also remain at high risk for poorer swallowing outcomes.

We are just beginning to understand the risk factors associated with long-term dysphagia after radiation or chemoradiation treatment. Studies have demonstrated that patients who have difficulty swallowing before treatment are also at higher risk for chronic dysphagia and permanent feeding tube dependency.18 Likewise, prolonged intervals of nothing per oral (NPO) longer than 2 weeks during radiation or chemoradiation treatment are associated with poorer swallowing outcomes.19 Therefore, it is important that patients are encouraged to eat and swallow as much as possible throughout the course of treatment, and even brief periods of NPO should be avoided.20

Finally, the viewpoint and preferences of the patient and the support of family and friends are essential components of treatment acceptance and compliance and ultimately long-term functional success. The psychological/psychosocial characteristics such as patient attitude, the attitude of the physician, particularly the surgeon, and the speech pathologist, and the attitude/support of the spouse or significant other have been found to be strongly related to successful functional outcomes. When the views of important others are nonsupportive, patients are less likely to achieve successful outcomes because of the detrimental effect on patient motivation, treatment adherence, and encouragement.21,22,23

The Interdisciplinary Team

Patients with cancer of the head and neck face multiple, often severe functional and psychological challenges associated with the diagnosis and treatment of their disease. Successful treatment for cancer of the head and neck and posttreatment rehabilitation depend on a strong, collegial interdisciplinary team for management. This is a point that cannot be overemphasized. Pretreatment evaluation and planning for functional rehabilitation should begin immediately after diagnosis and involve the entire oncologic care and rehabilitative team. After assessment and diagnosis by the surgeon, the patient should, at minimum, meet with the radiation oncologist, medical oncologist, dentist or maxillofacial prosthodontist, speech pathologist, nurse, dietitian, and social worker. Specialists from other disciplines such as physical therapists and psychologists, among others, may also be needed and should be called to help when indicated. In particular, the need for speech and swallowing therapy is often an unexpected recommendation that both the patient and family frequently find difficult to accept because the ability to speak and swallow after treatment is commonly anticipated to be regained automatically without need for intervention. Experience has shown that recovery and rehabilitation are optimized when there is ongoing dialogue between all members of the interdisciplinary team and information is similarly provided to the patient by all members of the group.

Evaluation

Standardized functional assessments remain a critical component of comprehensive patient care and outcomes research. Pretreatment examination should establish a baseline for treatment planning and later posttreatment comparison. Baseline evaluation is critical because it documents pretreatment function and often is helpful in predicting long-term outcomes. A complete functional examination includes clinical assessment that depends on clinician appraisal during physical examination, such as the bedside swallowing examination, cranial nerve examination, and oral motor assessment among others. Clinician-driven examinations also include instrumental and imaging studies, as well as clinician-rated scales. In addition, a comprehensive functional examination must also recognize patient perception and therefore include patientreported outcomes (PROs) such as quality-of-life questionnaires and symptom performance inventories.

Rehabilitation, and even more important, rehabilitative planning, should begin at the time of cancer diagnosis with patient counseling and a thorough baseline evaluation provided by a speech pathologist who is an expert in the evaluation and treatment of functional disorders associated with head and neck malignancies and their treatment. Baseline swallowing evaluation that includes instrumental examination, such as the modified barium swallow (MBS) study or flexible endoscopic evaluation of swallowing (FEES), documents important functional elements such as the presence of aspiration and airway protection that have been found to be strongly predictive of long-term swallowing dysfunction. Aspiration, vocal

fold paresis, feeding tube dependence, and tracheostomy prior to treatment have been reported as adverse prognostic indicators of posttreatment functional recovery.7 Moreover, aspiration of thin liquids sufficient enough to necessitate dietary modifications before cancer treatment or an NPO status prior to beginning treatment significantly predicts swallowing dysfunction requiring NPO status in long-term laryngeal cancer survivors.18 Additionally, it is important to determine the pretreatment effect of the cancer on swallowing as a decline in swallowing after radiation or chemoradiation treatment may not be related to fibrosis or posttreatment deconditioning but in fact may represent the loss of compensation for a cancerrelated dysfunction once the cancer has been cured.

fold paresis, feeding tube dependence, and tracheostomy prior to treatment have been reported as adverse prognostic indicators of posttreatment functional recovery.7 Moreover, aspiration of thin liquids sufficient enough to necessitate dietary modifications before cancer treatment or an NPO status prior to beginning treatment significantly predicts swallowing dysfunction requiring NPO status in long-term laryngeal cancer survivors.18 Additionally, it is important to determine the pretreatment effect of the cancer on swallowing as a decline in swallowing after radiation or chemoradiation treatment may not be related to fibrosis or posttreatment deconditioning but in fact may represent the loss of compensation for a cancerrelated dysfunction once the cancer has been cured.

Most important is that pretreatment baseline assessment provides critical information in select patients for whom survival is comparable regardless of surgical or nonsurgical alternatives but whose function, swallowing and voice, may be improved with one of either modalities. Baseline evaluation also helps to identify those patients with pretreatment dysphagia or who are at significant risk for posttreatment swallowing dysfunction to ensure therapeutic placement of gastrostomy tubes as opposed to the common practice of prophylactically placing feeding tubes in all patients. Recent data indicate that patients with pretreatment dysphagia, whether self-reported or documented by instrumental evaluation, treated with radiation ± chemotherapy for cancer of the oropharynx, experience more frequent placement and longer gastrostomy tube duration beyond 6 months than do patients with adequate oral intake prior to treatment (p < 0.001).24

Finally, the results from baseline evaluation provided during patient counseling offer realistic posttreatment functional expectations that frequently facilitate patient understanding, acceptance, and compliance with both cancer and rehabilitative treatment recommendations. Baseline evaluation allows clinicians to assess outcomes and draw conclusions that cannot be determined without appropriate pretreatment functional examination. It is for these reasons, among others, that pretreatment referral to speech pathologists for baseline functional evaluation has been recognized as best practice for all patients particularly for patients treated with nonsurgical organ preservation.25,26

METHODS OF EVALUATION

Clinical/Bedside

The clinical evaluation is useful because it is based on observation in a more natural, relaxed environment that is often representative of actual patient routine. However, it is important to remember that clinical observation lacks the sensitivity of instrumental examination. The most common clinical assessment of swallowing is often referred to as the bedside examination. The bedside swallowing examination always precedes the instrumental (MBS, FEES) study. It provides a basic screening to identify patients who have a “functional” swallow and who do not require instrumental examination. The clinical examination also allows the clinician to help determine the timing or readiness to begin oral intake. Not all patients require instrumental examination as these tests are often expensive and impractical and are associated with a resource burden that can be avoided when clinical examinations are performed accurately and in a timely fashion.

The clinician should obtain a thorough case history and perform a comprehensive evaluation of motor speech functioning that allows the development of a hypothesis of swallowing competency and dysfunction related to neurologic functioning and patterns of movement. Again, clinical examinations provide important information that is critical to the patient’s functional status. However, it is important to remember that bedside observation of swallowing function cannot reliably determine or rule out silent aspiration. Nor can observation reliably diagnose pharyngeal swallowing disorders because the problems that occur during the pharyngeal stage of swallowing must be inferred by the clinician. Despite this limitation, the examiner can detect signs and symptoms suggestive of pharyngeal swallowing impairments during clinical observation and evaluation. The goal of the clinical examination is to synthesize the overt as well as the subtle observations and use this knowledge to make recommendations including the need for further, more objective swallowing assessment.

Patient-Reported Outcomes

A variety of assessments are available to assess both speech and swallowing that include both quality-of-life and symptom performance scales. Measures of patient report rely on patient perception of functional status. Data, however, have shown that patients’ report of their functional status is frequently unreliable and more often does not accurately reflect physiologic performance and actual abilities.27 Patients frequently report normal swallowing despite abnormal findings of silent aspiration shown on MBS examination.28,29 Conversely, patients also report abnormal swallowing function associated with radiation-induced xerostomia despite functional MBS findings. Several noninstrumental tools have been shown to be good indicators of functional status particularly in patients with cancer of the head and neck. The Performance Status Scale for Head and Neck (PSS-HN) assesses three areas, normalcy of diet, understandability of speech, and eating in public, and is a simple clinician-rated tool that can provide valuable indicators of both speech and swallowing function.30 The MD Anderson Dysphagia Inventory (MDADI) is a 20-item patient-reported instrument, scored on a scale from 1 to 5, consisting of global, emotional, functional, and physical subscales that evaluate the effects of dysphagia on quality of life (QOL) from the patient’s perspective.31 Alternatively, the Functional Oral Intake Scale (FOIS)32 is another simple, validated tool that helps quantify the functional status of the patient with regard to feeding tube dependence and level of oral intake.

In addition, a variety of assessments are available to evaluate vocal functioning. Among them are the Voice-Related Quality of Life (V-RQOL),33 the Voice Symptom Scale (VoiSS),34 and the Voice Handicap Index (VHI-30)35 and its shortened version VHI-10.36 The Consensus Auditory-Perceptual Evaluation of Voice (CAPE-V)37 is a frequently used measure of voice perception that provides clinician-rated assessment of such vocal parameters as roughness, asthenia, breathiness, and strain.

Although there are multiple tools for assessing voice and swallowing function, there are relatively few assessments specifically designed for evaluation of speech intelligibility. The Speech Handicap Index has been validated for use in the head and neck population.38,39 Although the Assessment of Intelligibility of Dysarthric Speech40 has not been standardized for use in patients with cancer of the head and neck, it

provides valuable information regarding articulation for therapeutic planning that is often beneficial for patients with cancer of the head and neck. In addition, the understandability of speech component of the PSS-HN provides a simple and quick clinician-rated assessment of the intelligibility of speech production that is graded by a single score (0 never understandable to 100 always understandable).

provides valuable information regarding articulation for therapeutic planning that is often beneficial for patients with cancer of the head and neck. In addition, the understandability of speech component of the PSS-HN provides a simple and quick clinician-rated assessment of the intelligibility of speech production that is graded by a single score (0 never understandable to 100 always understandable).

The importance of patient experience and opinion as critical components of functional recovery and performance should not be disregarded. However, only instrumental examination, such as the MBS study or FEES, in the case of swallowing function, and direct observation of vocal fold function using endoscopy or stroboscopy, can provide physiologic information that ultimately identifies the etiology of dysfunction. Both anecdotal experience and research findings support the recognized discrepancy between patients’ perception of their handicap versus instrumental evaluations that examine physiologic aspects of function. Therefore, comprehensive examination should include both the findings from PRO measures along with those from instrumental evaluations of speech and swallowing abilities to ensure accurate interpretation of functional status.

Modified Barium Swallow Study

The most widely used and likely still the gold standard of instrumental swallowing evaluations remains the MBS examination, also referred to as the videofluoroscopic assessment of swallowing. This is because the MBS study evaluates the entire oropharyngeal swallow, from the point at which the food passes the lips to the time it enters the cervical esophagus. The MBS study is performed jointly by a speech pathologist and a radiologist. The examination should be performed in standard fashion including the use of radiopaque liquids, pastes, and solid consistencies as swallowing physiology will vary depending on the consistency and the amount of food presented. The MBS study is the examination of choice for swallowing assessment versus the traditional barium swallow study or esophagram, the purpose of which is to evaluate the structural integrity of the pharyngoesophagus and identify aspiration during continuous swallowing of a large liquid bolus. Furthermore, the barium esophagram does not provide the information necessary to identify dysfunction of oropharyngeal swallowing nor do the results allow a differential diagnosis of the etiology of aspiration.

The primary purpose of the MBS examination is to understand oropharyngeal swallowing physiology as it relates to swallowing dysfunction. A number of important observations can be made from the MBS study that include the presence of penetration of swallowed material into the laryngeal vestibule and the degree of aspiration into the trachea using the validated Penetration-Aspiration Scale.41 The efficiency of the swallow can also be measured and quantified with the oropharyngeal swallowing efficiency (OPSE) score.42 In addition, the Dynamic Imaging Grade of Swallowing Toxicity (DIGEST) scale offers a novel grading schema that summarizes the interaction between swallow safety measured by penetration aspiration events and swallowing efficiency estimated by pharyngeal residue, in a psychometrically validated scale. One of the advantages of the MBS study is that the examiner can immediately assess the effectiveness of selected swallowing techniques and strategies to relieve the dysphagia during study administration.43 Most important, videofluoroscopic findings during MBS examination document swallowing physiology, laryngeal sensation, and aspiration and have been reliably associated with health risk prediction rates particularly for pneumonia.29

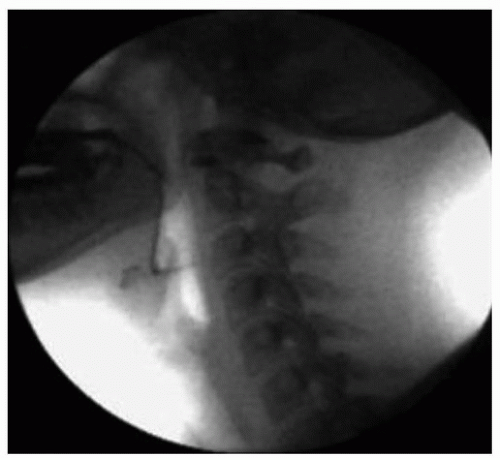

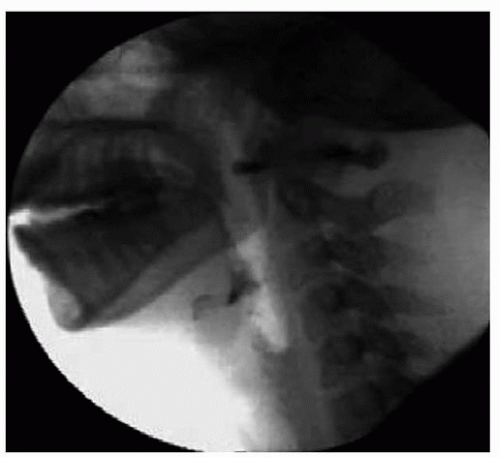

Figure 33.2. Normal swallowing results during MBS examination. Note the lack of tracheal aspiration or oropharyngeal residue after the swallow is completed. |

Figure 33.1 shows a lateral radiographic view of normal oropharyngeal anatomy prior to swallow initiation during the MBS study. No evidence of aspiration or residue is seen following swallowing completion as shown in Figure 33.2. Figure 33.3 demonstrates aspiration associated with disordered swallowing function.

Flexible Endoscopic Evaluation of Swallowing

In some cases, FEES provides an excellent alternative to the MBS study because it can be easily performed as a clinical procedure or at bedside for patients who cannot tolerate or are not candidates

for videofluoroscopic examination of swallowing. FEES uses a flexible endoscope placed transnasally to examine the pharyngeal swallow while providing direct visualization of laryngeal anatomy. FEES has been shown equally effective to the MBS study in detecting aspiration and does not expose the patient to radiation.44 It is often preferred for patients who have cancer of the larynx because it provides the best view of glottic competency, including airway protection and vocal fold mobility. An additional advantage of FEES is that it can be paired with simple sensory testing to help determine laryngeal sensitivity unlike the MBS study in which this is difficult to do.45 Furthermore, it provides the patient with immediate biofeedback and visualization that are often useful during therapy sessions.

for videofluoroscopic examination of swallowing. FEES uses a flexible endoscope placed transnasally to examine the pharyngeal swallow while providing direct visualization of laryngeal anatomy. FEES has been shown equally effective to the MBS study in detecting aspiration and does not expose the patient to radiation.44 It is often preferred for patients who have cancer of the larynx because it provides the best view of glottic competency, including airway protection and vocal fold mobility. An additional advantage of FEES is that it can be paired with simple sensory testing to help determine laryngeal sensitivity unlike the MBS study in which this is difficult to do.45 Furthermore, it provides the patient with immediate biofeedback and visualization that are often useful during therapy sessions.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree