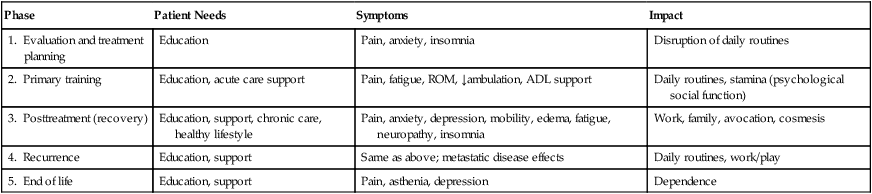

• As cancer treatment improves, more patients are living longer with functional limitations, and quality of life issues become as important as survival. • Rehabilitation must be patient centered and goal oriented. It requires an interdisciplinary team and the active participation of the patient. • Impairments, activity limitations, and participation restrictions from cancer dramatically impact quality of life but are amenable to rehabilitation efforts. • The focus of rehabilitation varies with the phase of the disease process. • Important impairments include pain, fatigue, cognitive dysfunction, mood disorders, paresis, feeding difficulties, bone and soft tissue involvement, and bladder, bowel, and sexual dysfunction. • Activity limitations can be ameliorated with training in activities of daily living, exercise, and adaptive equipment. • Participation in home, vocational, and recreational activities plays a critical role in quality of life. Economic burdens, environmental barriers, and transportation problems often need to be addressed. The National Cancer Institute Dictionary of Cancer Terms defines rehabilitation as “a process to restore mental and/or physical abilities lost to injury or disease, in order to function in a normal or near-normal way.”1 Rehabilitation is critical to improving quality of life (QOL) for cancer survivors and maintaining dignity for persons with terminal illness. Rehabilitation requires several components to be successful. The World Health Organization has recently published an International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health, which is meant to supplement the International Classification of Disease (ICD-10).2 It presents a series of definitions that are crucial to understanding the role of rehabilitation in improving quality of life. These definitions are listed in Box 55-1. In this chapter, we will focus on impairments, activity limitations, and participation restrictions in patients with cancer and discuss how rehabilitation can ameliorate these disabilities. The number of cancer survivors continues to grow because more people are living longer with cancer as a result of new advances in surgery, medical, and radiation oncology.3 The result is that increasing numbers of patients face more years with cancer-related disability. Cancer survivors who are older than 55 years have significantly more pain and deficits in self-care and mobility than do control subjects.4 Focus needs to be directed away from mere survival toward the preservation and improvement of QOL for these survivors. In Japan, for example, the number of breast cancer survivors with lymphedema and pain in the chest wall, axilla, and arm is expected to double by 2020.5 Patients with cancer can benefit from rehabilitation at every phase of the disease (Table 55-1). Clinicians should ask the patient the simple question: “Has your ability to function changed?” Because cancer is a complex, chronic illness, management requires vigilance and a comprehensive and preventive approach to illness and disability. The major concerns of persons with cancer include their overall health, fitness, fatigue, emotional and social function, and pain, which may vary during different phases of the disease. For example, in the initial phase, anxiety and disruption of routines may present the greatest challenges. During the treatment phase, fatigue, nausea, and sleep disruption may be the most significant problems. If the patient is having difficulty with mobility, self-care, fatigue, or pain, referral to a cancer rehabilitation program may be appropriate. Guidelines for referral for breast cancer rehabilitation have been published.6 Table 55-1 Phases of Cancer Rehabilitation Virtually every patient with cancer experiences pain during the course of the illness, and the pain often can become debilitating.7 Pain severity correlates closely with function, as demonstrated in one study of 216 Chinese patients with cancer who had metastatic disease.8 In that study, patients with increasing severity of pain had poorer function, whereas patients with mild, well-controlled pain functioned similarly to persons without pain. Cancer-related fatigue has been described as “overwhelming and sustained exhaustion and decreased capacity for physical and mental work…not relieved by rest.”9 In addition, fatigue has been shown to have a negative impact on one’s economic status, social, and emotional status.10 It has been demonstrated that improving the quality of sleep is helpful, but increasing the amount of “rest” is not effective in reducing the symptoms of cancer-related fatigue.11 Exercise has been shown to mitigate fatigue.12 A further discussion of fatigue is provided in Chapter 45. In studies of patients with advanced cancer, the incidence of delirium ranges from 20% to 86%.13 Delirium may be reversible in 50% of cases with proper identification and management.14 The etiology of delirium in persons with cancer is usually multifactorial. Accurate assessment is critical for effective treatment. Risk factors for the development of delirium in patients undergoing bone marrow transplant before transplantation included lower cognitive function, lower physical function, and higher blood urea nitrogen, alkaline phosphatase, and magnesium levels.15 Medications play a large role in the development of delirium. In a study of 216 hospitalized patients with cancer, use of corticosteroids, opioids, and benzodiazepines was most frequently associated with delirium.16 The clinician must also consider metabolic factors. Fever and sepsis often produce acute delirium, and dehydration and uremia frequently contribute to the condition. Hypoxia and hypoglycemia are additional factors that can be easily assessed. Patients with cancer often report cognitive difficulties after chemotherapy and other treatment regimens. However, a new study indicates no significant differences in the long-term cognitive function of cancer survivors versus control subjects.17 Many of these reports of cognitive difficulty may relate to fatigue. Although most patients cope well, a significant number experience serious mood disorders. Estimates of the prevalence of depression among patients with cancer range from 15% to 25%.18 Anxiety is quite common and may be related to poorly controlled pain, abnormal metabolic states, or medication-related adverse effects. Patients may also experience posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in response to cancer diagnosis and treatment. PTSD is an anxiety disorder that develops after an extremely stressful event, such as the development of a life-threatening illness. Within 5 years of diagnosis, between 10% and 15% of cancer survivors may meet the criteria for PTSD.19 Brain tumors vary widely in aggressiveness and prognosis. The extent to which tumor type or location has an impact on rehabilitation outcomes is not clear. However, one study found a tendency for greater gains in patients with meningiomas and left hemispheric lesions. Patients receiving inpatient acute rehabilitation show similar gains regardless of whether they have a primary brain tumor or a brain tumor resulting from metastatic disease.20 Some studies have shown that patients with a brain tumor have shorter lengths of stay on acute rehabilitation units compared with patients who have other noncancerous brain disorders.21 Most patients with brain tumors have multiple impairments depending on tumor location and size and the volume of tissue excised at surgery. In a study of patients undergoing acute rehabilitation, the most common neurologic deficits included impaired cognition (80%), weakness (78%), and visual-perceptual dysfunction (53%).20 Rehabilitation efforts should focus on the patient’s neurologic and functional status, co-existing medical problems, and tolerance of physical activity. As for patients who have had a stroke or traumatic brain injury, goal setting should be appropriate to the individual’s physical, cognitive, and behavioral status and include early planning for postacute rehabilitation care. The incidence of cancer-related spinal cord injury (SCI) may exceed that from trauma and represents the most frequent type of nontraumatic SCI.21 Spinal cord metastases produce a clinical syndrome characterized initially by pain in 90% of cases, followed by weakness, sensory loss, and sphincter dysfunction. Weakness is present in 74% to 76% of patients, autonomic dysfunction is present in 52% to 57% of patients, and sensory loss is present in 51% to 53% of patients.22,23 Pain alone may persist for a month or more (average 6 weeks) before significant neurologic changes develop. Acute onset of back or neck pain in a patient with cancer should be considered to be spinal metastasis until proven otherwise. Positive results have been demonstrated after rehabilitation for persons with disability from spinal cord tumors.22

Rehabilitation of Individuals with Cancer

Introduction

Epidemiology of Cancer Disability

Which Patients Should be Referred for Cancer Rehabilitation and When?

Phase

Patient Needs

Symptoms

Impact

1. Evaluation and treatment planning

Education

Pain, anxiety, insomnia

Disruption of daily routines

2. Primary training

Education, acute care support

Pain, fatigue, ROM, ↓ambulation, ADL support

Daily routines, stamina (psychological social function)

3. Posttreatment (recovery)

Education, support, chronic care, healthy lifestyle

Pain, anxiety, depression, mobility, edema, fatigue, neuropathy, insomnia

Work, family, avocation, cosmesis

4. Recurrence

Education, support

Same as above; metastatic disease effects

Daily routines, work/play

5. End of life

Education, support

Pain, asthenia, depression

Dependence

Impairments

Pain

Fatigue

Delirium and Cognitive Dysfunction

Mood Disorders

Neurologic Impairments

Hemiplegia

Paraplegia and Tetraplegia

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Rehabilitation of Individuals with Cancer