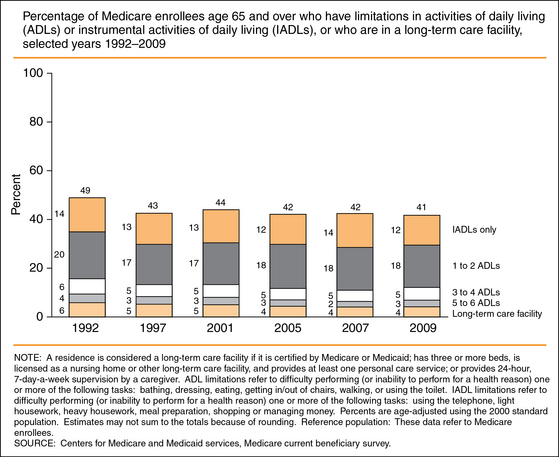

13 Rehabilitation and the Older Individual Prevention of Functional Decline and Anticipatory Planning Prevention of Deconditioning During Acute Illness Gait Rehabilitation, Hip Replacements, and Fractures Rehabilitation in Cancer Patients Aging with a Long-Standing Disability Rehabilitation in Setting of Multiple Comorbidities Rehabilitation and Cognitive Problems Upon completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to: • Understand the burden of functional impairment in the older individual. • Appreciate how level of function may fluctuate over time in an individual. • Appreciate the role of rehabilitation in common diseases of the older individual. • Understand how to support the rehabilitative needs of the patient within the primary care setting. The goal of rehabilitative care of older individuals is the prevention or delay of the onset of disability, and there is accordingly great attraction to the idea of directing rehabilitation efforts to the frail elderly.1 Although there is a modest role of genetic factors in the risk for functional impairment in old age, environmental factors appear to be far more important.2 Rehabilitative care is one strategy for improving the mix of environmental factors to promote best function. Rehabilitation efforts for frail elders may be directed to avoid loss of function, to help promote return of lost function, or both.3 Determining if an older adult is a candidate for rehabilitation is not always clear. Among older individuals, there are many who do not have obvious disability, but in fact have already made subtle alterations in their activity pattern in response to a mild decline in function.4 Many of these individuals may benefit from early preventive rehabilitation efforts, sometimes referred to as “prehabilitation.” Such efforts may be directed to improve present function and potentially could also decrease the risk of progression to more frank disability. In some cases this may involve encouraging compliance with general healthy lifestyle recommendations about physical activity. This kind of early rehabilitation may provide a physiologic reserve that can help the individual better tolerate a future loss of function during a future illness. In one meta-analysis, interventions to improve function, and avert nursing home placement, were moderately effective. The absolute benefit of rehabilitation in this regard appeared to be greatest in the patients at the highest baseline risk for future nursing home placement, with a number needed to treat (NNT) of 39 to see this benefit.5 Many older individuals will cycle over time between being disabled and having no disability,6 rather than simply showing a linear course of relentlessly increasing disability. Seen in that light, it is reasonable to regard the hospitalization for an acute medical illness as an event that increases the risk that the patient may transition from no disability to disability.7,8 Similarly, rehabilitation interventions in the acute medical setting can be considered as an effort to foster rapid transition back from the disabled state to the prior higher level of function. On the other hand, if patients following their acute medical illness later reach a level of disability where they require nursing home admission, the prognosis for a full reversal of their disability is much more guarded. In one study,9 following such a nursing home admission, only 32% of the nursing home admittees made a full recovery of function. In light of these several studies, a strong case can be made for the use of postacute rehabilitation as a strategy to decrease the risk for future nursing home placement and the risk for later progression of disability. An individual’s level of disability is determined not just by physical and mental function. This broader view is embodied in the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health: “Functioning and disability are viewed as a complex interaction between the health condition of the individual and the contextual factors of the environment as well as personal factors. The picture produced by this combination of factors and dimensions is of ‘the person in his or her world.’ The classification treats these dimensions as interactive and dynamic rather than linear or static.”10 Functional impairment is common among older persons, not just the small minority (5% of those aged 65 years and older) who reside in nursing homes. Of all Medicare enrollees aged 65 and older, 14% of the men and 23% of the women are unable to walk two to three blocks. There is evidence that some measures of age-adjusted rates of disability in the United States have declined, although with the growth in the total population older than age 65, the absolute number of chronically disabled older individuals has modestly increased11 (Figure 13-1). Figure 13-1 Percentage of Medicare enrollees aged 65 and older who have limitations in activities of daily living (ADLs) or instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs), or who are in a long-term care facility, selected years 1992-2009. (Courtesy of the Federal Interagency Forum on Aging-Related Statistics. Older Americans 2012: Key indicators of well-being. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; June 2012. Available at www.agingstats.gov/Main_Site/Data/2012_Documents/docs/EntireChartbook.pdf.) In the older patient, there is often more than one condition that can contribute to disability. A 1996 survey found that, of Medicare patients aged 65 years and older, 64% had at least one potentially disabling condition (blindness or low vision, deafness or hard of hearing, difficulties walking, difficulties reaching overhead, difficulties grasping and writing), and 30% had more than one of these conditions.12 The two most common areas of reported difficulty are in hearing and walking, both of which can benefit from medical attention, but for which the rehabilitative strategies are substantially different. Significant hearing deficits are likely to require provision of a hearing aid, and support by the clinician to encourage the patient to obtain it and to use it once prescribed.13 Difficulties with gait may reflect one or a combination of deficits (muscle weakness, postural instability, poor vision, peripheral neuropathy), for which the appropriate choice of management will depend in large part on the clinician’s evaluation of the relevant contributory factors for the patient. Rehabilitative strategies for older patients with weakness can be successfully linked to skills necessary to perform ADLs, rather than simply focused on increasing strength.14 This may make it easier to design regimens that can directly improve functional ability, and which can be readily reinforced during physical activity while performing daily tasks. The evaluation of function should be tailored to the individual patient’s situation, and may incorporate consideration of both objective and subjective information. It can include assessment of motor strength on the neurologic examination, as well as evaluation of the patient’s ability to perform ADLs (e.g., getting out of bed to go to the bathroom) and instrumental ADLs (e.g., grocery shopping). The degree to which patients are disabled by a loss of function depends in part on what they consider normal, as well as by their level of social supports. Even if they can still accomplish a task such as walking to go grocery shopping, they may have noted that it involves more pain from knee osteoarthritis, that they have to do it differently such as buying smaller numbers of bags at each trip, and/or that it takes more time to walk to and from the grocery store.15 These early complaints may foreshadow the risk of being unable to accomplish the task of grocery shopping at all. Ideally, rehabilitation can aid in pain management but also simultaneously support other health goals such as maintaining physical fitness. A Cochrane review16 examined the database in support of the use of aquatic therapy for patients with osteoarthritis of the knee or hip. This review suggests that there may be some short-term benefit in terms of pain control, but it concludes that the evidence base is quite weak regarding the role of aquatic therapy for osteoarthritis. Certainly aquatic therapy is widely recommended in daily practice, often to promote a wider variety of therapeutic aims than just pain management. Other therapeutic objectives may include maintaining coordination and balance, avoiding deconditioning, and promoting social interaction in a group activity. Rehabilitation of older adults can take place in an acute hospital medical or rehabilitation unit,17 the nursing home, an outpatient area, or the patient’s home. The ability to provide in-hospital rehabilitative care to Medicare beneficiaries has been influenced by changes in reimbursement formulas. Between 1994 and 2001, the median length of stay for inpatient rehabilitation fell from 20 days to 12 days.18,19 Skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) may also deliver rehabilitation services to many of their residents, typically at a lower level of intensity than patients would receive in a hospital facility, and such services may enable the resident to regain enough function to leave the nursing facility and return to the community.20 Changes pursuant to the Balanced Budget Amendment of 1997, however, not only have affected the reimbursement structure for rehabilitation hospitals,21 but also have made it less financially attractive for SNFs22 to offer their residents rehabilitation services. The ongoing changes in the Medicare program23 are likely to have a significant impact on the availability of rehabilitation services across a variety of care settings. The pressure of the Prospective Payment System on inpatient rehabilitation facilities for prompt discharge may have contributed to a pattern of discharges from inpatient rehabilitation often being directed not to discharge home, but rather to an SNF.24 The payment schema in turn places strong incentives on the SNFs to control the intensity of the care they provide; Medicare provides reimbursement to the SNF for rehabilitative care to a certain point, but therapy beyond 720 minutes per week offers no marginal reimbursement.25 Yet another Prospective Payment System methodology has been adopted in the home health setting, creating a financial incentive for the home health provider to limit overall home visitors.26,27 In an era when brief hospital stays limit the ability for inpatient rehabilitation, unmet rehabilitative need is a common occurrence. Over the last decade, the federal government through its Medicare statutes and regulations has tried to control the growth of postacute rehabilitation services, but with only limited success. In some cases, the effect of the Medicare reimbursement rules appears to have been less to discourage the provision of postacute rehabilitation than to create incentives to shift the care site where rehabilitation is offered (e.g., for the postacute care to be offered in an SNF rather than in the home setting with home health care).28 Medicare is estimated to have paid $42.1 billion for postacute rehabilitation services in 2005.29 At the same time, there is also Medicare data to suggest that many older individuals do not receive any rehabilitative services at all even though their diagnosis suggests that they might likely have benefited from such services.30 Inpatient rehabilitation facilities in particular are under fiscal pressure from Medicare to assure that 75% of their admissions fall in one of 13 diagnostic categories, including entities such as stroke or hip fracture, in order to maintain their status as an inpatient rehabilitation facility.31 This Medicare funding restriction may make it more difficult to obtain postacute inpatient rehabilitation for older patients who have hospital-associated deconditioning but who do not fall within one of the 13 diagnostic categories. Further changes in the medical economic milieu for rehabilitation are likely to occur as the implementation of the Affordable Care Act proceeds.32 (See Chapter 8.) A report on Canadian stroke care33 has documented the need to better integrate stroke rehabilitation into the process of stroke care in Canada, and from a perspective in the United States it is noteworthy how similar the issues and challenges are in the Canadian setting. For example, a Canadian study of hemodialysis patients scheduled their rehabilitation to fit with their 6-times-per-week hemodialysis schedule. This integration of medical and rehabilitative care aids in addressing goals relevant to both interventions (protein intake, mobility, patient fatigue) as part of the patient’s overall care.34 Coordination of the various aspects of care for the patient can significantly help to minimize the cost of care, such as reducing the need for transportation services. Another economical strategy, particularly for patients with less severe levels of impairment, may be to deliver therapy in a group treatment setting.35 In the case of patients residing in a nursing home, the impairments are likely to be substantial and multiple;36 they may be relatively easier to recognize but the process of rehabilitating them may be relatively more complex. Among nursing home residents, for example, those with new impairment in voluntary movement or in range of motion are at particular risk for a decrease in their ability to perform the ADLs.37 The rehabilitation goals for the long-term nursing home resident are likely to be different and more modest, and a successful outcome may be to maintain level of function rather than to achieve full independence. Rehabilitation regimens will often need tailoring to the abilities of the frail older individual. Even for those individuals in the nursing home setting, there is reason to suspect that many could benefit from an increased level of therapy, both that delivered formally by therapists and that received from the bedside nursing staff. A study of patients in SNFs demonstrated that patients had a more rapid increase in their functional status, and a greater chance of leaving the nursing home to return to the community, if they were in a facility where the average resident received at least 1.5 hours of therapy per day. Likewise, both the rate of increase in functional status and the chance of returning to the community were higher for patients who were in SNFs that provided higher levels of nurse staffing.38 Older medical inpatients may often be discharged from the hospital at a time when they are stable from the point of view of their recent acute medical illness, such as a stroke, but when they have not yet completed their process of rehabilitation from the acute medical event. In this situation, it is important to plan for the postdischarge component of their overall rehabilitation pathway. Otherwise, the risk is that the momentum of their rehabilitation may be lost.39,40 The transition to home-based rehabilitation postdischarge allows the opportunity for the therapy to be more precisely tailored to the specific home environment, and for the patient and caregivers to be more active participants in that tailoring process.41 A particular concern in the discharge planning process is to make sure that the course of rehabilitation is not delayed (or prematurely interrupted) by the transition from the acute hospital setting to the postdischarge setting (such as home or nursing facility). Delayed rehabilitation efforts may not be nearly as effective as efforts begun more promptly. For a stroke patient, even a 1-month delay in beginning poststroke rehabilitation has been associated with a poorer rehabilitation outcome.42 The postdischarge course of rehabilitation may be adversely affected by medical complications following discharge, such as aspiration pneumonia in the stroke patient when he or she eats at home. The course of the stroke patient at home in the postacute period may be further complicated by psychological factors, including anxiety or depression.43 In frail older patients, particularly if they are homebound, their postacute needs for rehabilitative and emotional support may often go unrecognized and so unaddressed. A comprehensive approach to meeting postacute care needs for the patient who returns home may include provision of assistive devices such as wheelchairs, incorporation of family caregivers into the home care plan, and/or modification of the bathroom or other architectural components of the patient’s home.44 In general, one can best think about rehabilitative needs of the patient across the continuum of care, not just in a particular care setting. The less opportunity there is for rehabilitation in one setting, the more likely it is that the patient will require rehabilitation interventions at another point in the care continuum. Rehabilitative needs that are not fully addressed during the patient’s acute inpatient hospitalization are likely to require increased rehabilitation interventions in the patient’s postacute care. Likewise, patients with major medical illnesses such as cancer45 may receive rehabilitative interventions in a rehabilitation setting, but they are often liable to need transfer back to the acute medical inpatient setting if their medical condition worsens.46 Rehabilitation is an approach to care provided by a team of professionals. Although physicians specializing in physical medicine and rehabilitation, physical therapists, and occupational therapists are most closely identified with rehabilitation practice, the rehabilitation approach is applicable to older patients being cared for by geriatricians, primary care physicians, orthopedists, neurologists, nurses, psychologists, social workers, and most other health care professionals. In a given case, all rehabilitation disciplines involved will have a discipline-specific focus to their portion of the comprehensive assessment. Table 13-1 lists and briefly describes the roles of various rehabilitation professionals. TABLE 13-1 Roles of Rehabilitation Team Professionals Adapted from Warshaw GA. Rehabilitation and the aged. In: Gallo JJ, Busby-Whitehead J, Rabins PV, et al, editors. Care of the elderly: Clinical aspects of aging. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1999, p. 275. In planning for the primary care of an older individual, even one without current functional limitations, it is useful to consider with the patient the possibility that he or she may become frail in the future. Individuals may vary over time in their degree of disability47 and in their needs for rehabilitation. Intermittent episodes of disability may be a marker for underlying frailty, and they may contribute to worsening frailty by leading to inactivity and deconditioning. Among the community-dwelling elderly, a commonly reported pattern is to spend occasional brief (one to several days) episodes at bed rest because of illness, injury, or other complaints. Patients with a history of episodic bed rest are at increased risk for functional decline.48 Various clinical interventions have been evaluated to test their impact on preventing disability. A detailed multispecialty evaluation of each older patient’s functional status may be difficult to accomplish in routine primary care practice, and the yield may be relatively small.49 One strategy for increasing the yield of rehabilitative care is to focus on situations of highest risk. Clinical situations that pose a particular risk for the onset of disability are hospitalizations (particularly after a fall) and episodes of restricted physical activity.50 These clinical situations may be particularly fruitful settings for a focus on measures to decrease the risk for incident disability. One of the important preventive measures in primary care is to encourage physical activity, to help patients achieve a higher level of baseline function, so that they will have more functional reserve. Patients who later experience a functional decline may regain some or all of their functional loss, but they are at high risk for losing function again in the near future. They are more likely to recover their independence of function, and to maintain their regained independence of function for a longer period of time, if they have a baseline pattern of habitual physical activity.51 Low-cost rehabilitative strategies may be most feasible for community-dwelling patients in generally stable condition.52 These may be as straightforward as group exercise programs. In many cases, these strategies will be able to establish a higher functional status for the patient, so that if the patient has a subsequent decline in functional status it will not produce as severe a degree of functional deficit. Deconditioning is a common occurrence in the hospital setting during an acute medical illness.53 The temporal association raises the concern that deconditioning may result not only from the medical illness that led to the hospitalization, but also from the hospitalization itself. In order to maintain mobility independence, adequate lower extremity strength and speed are important, as is balance.54 Even a brief hospitalization tends to produce declines in mobility, limb strength, and even of respiratory muscle strength. A study of brain-dead organ donors who were maintained on a ventilator for 18 to 69 hours demonstrated that, even in that brief interval on a ventilator, diaphragmatic muscle atrophy occurred of both slow and fast muscle fibers.55 Unnecessarily restricting the patient to bed rest is certainly a strategy to be avoided, but functional declines can be anticipated to occur even if the hospitalized patient has not been ordered to stay in bed.56 Rehabilitative strategies to prevent or treat deconditioning, therefore, must consider not just the acute medical illness but also the hospital environment, with active consideration of how to integrate rehabilitation into the overall pattern of care. One strategy that has been employed to prevent deconditioning is a multidisciplinary intervention to promote early mobilization, including involvement by a physiotherapist early in the hospitalization and exercises at least twice a day. This kind of approach did not aim merely to get the patient up from bed to chair, but rather was able to get the patient to spend substantial amounts of time standing and walking.57 An important tactic to maintain function in the acute medical patient is to minimize the risk factors for functional decline. One goal of inpatient rehabilitative interventions will often be to prevent further medical complications. In the stroke patient with dysphagia, for example, swallowing rehabilitation potentially can decrease the risk for aspiration pneumonia. Aspiration pneumonia in the stroke patient conversely may be associated with a poorer rehabilitative outcome from his or her poststroke rehabilitation.58 Worsening of acute medical condition is a common cause for interruption of rehabilitation efforts, with the risk that the efforts may never be resumed.59 The multiple demands placed on the patient by inpatient procedural care, delivered on the institution’s schedule, may often conflict with the patient’s typical rhythm for sleep and for meals. Of note, the hospitalized patient’s normal pattern of sleep architecture can also be significantly disrupted, even if the total amount of sleep in a 24-hour cycle is maintained by multiple short fragments of sleep time throughout the night and day.60,61 In combination, the resultant sleep pattern disruption and negative nutritional impact can leave the fragile older patient poorly equipped to maintain his or her functional status. Patient who have had disrupted sleep may also have impaired daytime alertness, which can affect their ability to participate in rehabilitation and other aspects of their care. Patients may attempt to adjust to their gait problems by using strategies such as walking more slowly. Slower walking speed by itself may prove a good compensatory strategy when walking on difficult terrain for older individuals in good health,62 and even for those with exercise limitations from mild chronic stable angina, but is much less likely to compensate for the effects of diabetic peripheral neuropathy on proprioception.63 One component of therapy for patients with gait limitation is likely to be physical activity tailored to patient abilities. Frail older patients who engage in even very modest amounts of informal exercise (walking more than one block per day) are likely to preserve their residual mobility better than patients who are more sedentary.64 Patient selection for rehabilitation should not be restricted by chronologic age, as appropriate patients even in their 90s have been shown to derive benefit from a rehabilitation program.65,66 Primary clinicians are in an excellent position to encourage increased physical activity by their patients. One strategy to do so is to identify particularly those patients who are already in the contemplative phase of considering an exercise program, and then to target them with motivational advice and educational materials on the benefit to them of exercise.67 Printed patient educational materials are far less likely to be useful, however, in meeting the rehabilitation needs of patients who are more acutely ill,68 particularly if they may suffer from delirium or dementia. These mobility aids can also be associated with falls. The very reason that individuals were prescribed a cane or walker may have been that their gait was unsteady and they were diagnosed as a fall risk. Use of an assistive device can interfere with the patient’s ability to use a stairway banister or a wall for stability. The patient can potentially trip over the device itself. Further, use of a cane or walker requires the person to change his or her customary way of walking, a task that may be difficult to master, particularly in the older patient with cognitive impairment.69 Rehabilitation efforts are likely to be even more challenging if the older patient has required an amputation,70 such as for diabetic complications. Rehabilitation therapy can be of benefit to older individuals with a variety of musculoskeletal conditions,71 including those with lower extremity fractures or following joint replacement surgery. A rehabilitation program is often an important part of the postoperative course of the older patient. The patient may often derive great benefit if the rehabilitation is begun in the early postoperative period in the hospital, rather than being delayed until the patient is discharged from the acute care setting. In one small study of patients who had unilateral hip replacement, early postoperative rehabilitation shortened the mean length of stay in hospital by 6 days.72 Unfortunately many older individuals will fail to adhere to recommendations for postoperative exercise in the months after they return home.73 One study of inpatient falls in a rehabilitation center found that almost 19% of the residents fell at least once, some more than once, but that fractures were uncommon. In this series of 1472 total patients, 140 patients fell at least once; there were 171 falls in total, but only two fractures resulted from the 171 falls. The falls generally did not occur during therapy sessions, but rather mostly occurred when patients were alone unobserved in their room (typically when they were attempting to transit to the bathroom).74 The important point is that gait rehabilitation should be regarded as a beneficial rather than risky activity.

Rehabilitation

Rehabilitation and the older individual

Rehabilitation settings

Rehabilitation team

Physiatrist (physical medicine–trained MD)

Evaluates patient, integrates assessment data, determines potential, coordinates rehabilitation plan

Primary Care Physician

Manages acute and chronic medical care

Rehabilitation Nurse

Integrates medical, nursing, rehabilitation plan

Physical Therapist

Addresses mobility, strength, range of motion

Occupational Therapist

Addresses activities of daily living and self-care

Speech Pathologist

Addresses communication, swallowing

Psychologist and Neuropsychologist

Diagnosis/treatment of mood, behavioral, and cognitive conditions

Social Worker

Works with family, patient, financial counseling, discharge planning

Nutritionist

Assesses nutrition status, diet plan

Pharmacist

Reviews medication use

Audiologist

Provides hearing assessment and treatment

Vocational Counselor

Evaluates work potential, provides training

Recreational Therapist

Assists with hobbies, leisure activities, motivation

Orthotist/Prosthetist

Makes and fits orthopedic aids

Prevention of functional decline and anticipatory planning

Prevention of deconditioning during acute illness

Gait rehabilitation, hip replacements, and fractures

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Oncohema Key

Fastest Oncology & Hematology Insight Engine