Fig. 12.1

The major components of the Common Technical Document (CTD)

Recent History in the FDA Review Divisions

More recent history of the FDA reviews involved in cardiometabolic therapeutic regulation is relevant to early-phase investigation. This starts with understanding some evolutionary differences between what are now called the Division of Metabolism and Endocrinology Products (DMEP) and Division of Cardiovascular and Renal Products (DCaRP). DMEP maintains much of its heritage of approving drug products on the basis of reversing classic endocrine deficiency states or reducing abnormal metabolites such as blood glucose and cholesterol levels. DCaRP has always had more of a focus on clinical outcomes, but this was accentuated by its experience with the Cardiac Arrhythmic Suppression Trial (CAST) [10]. In short, a class of drugs for treating ventricular arrhythmias was approved based on reduction of premature ventricular contraction rates, a surrogate endpoint expected to predict clinical benefit. CAST was a post-approval outcome trial that demonstrated a substantial disadvantage of these drugs on survival. Almost all DCaRP approvals have since been based on outcome studies. The exception is approval of antihypertension agents, which continue to be based on reduction of blood pressure. DCaRP approved the first indication for treatment of diabetic nephropathy, the angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEI) captopril, on the basis of doubling of serum creatinine [11]. Compared to a simple treatment effect on creatinine clearance, creatinine doubling has been viewed by the expert community as a quasi-clinical outcome, proximate to end-stage renal failure [12]. Other ACEI and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) have since been approved for this indication, and the indication has been extended to include patients with type 2 diabetes. The only other diabetic complication indication approvals have been for diabetic macular edema [13] despite over two decades of major effort to develop aldose reductase inhibitors for diabetic peripheral neuropathy and other diabetic complications [14].

DMEP continues to approve therapies for diabetes on the basis of glycemic control as reflected by haemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol-lowering agents on the basis of LDL cholesterol reduction [15, 16]. However, because of the controversy surrounding the increase of cardiovascular risks related to the thiazolidinedione agent rosiglitazone (Avandia™) [17], DMEP has required data from cardiovascular outcome trials to rule out a defined level of risk for increasing major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) before approval of drugs for type 2 diabetes [18]. In addition to accepting LDL-C reduction as the regulatory efficacy endpoint for cholesterol-lowering drugs, DMEP continues to accept reduction of very high levels (>500 mg/dL; >5.56 mmol/L) of triglyceride as a regulatory endpoint for reduction of high triglyceride levels (and specifically not for reduction of cardiovascular risk) [19]. However, all other non-LDL lipid-lowering indications aimed at cardiovascular risk reduction, including triglyceride-lowering agents, require outcome trials [20]. Even some doubt has been raised about LDL cholesterol as continuing to be a suitable regulatory endpoint [21].

Though these more recent issues pertain to late-stage and post-approval therapies, this understanding is relevant to early-stage investigation for several reasons. DMEP is busy, stressed, and perhaps more risk averse, which can have an impact on early IND review. Regulatory endpoints for assessment of efficacy in the metabolic space, such as HbA1c and LDL cholesterol, are also increasingly debated. Even at the earliest phases of clinical investigation, sponsors are being pressured to show evidence of both safety and efficacy that is superior to currently marketed products [22]. Early-phase investigators benefit from understanding these dynamics since difficult benefit/risk judgments that must be made at the approval stage have an impact even on DMEP’s review of initial in-human studies.

How Therapeutic Products Are Regulated at FDA

FDA is a vast organization with regulatory responsibility for more than $1 trillion worth of consumer goods, roughly a quarter of consumer expenditures in the USA. This includes $466 billion in food sales, $275 billion in drugs, $60 billion in cosmetics, and $18 billion in dietary supplements [23]. Unlike any other therapeutic regulatory authority in the world, FDA has an enormous staff of experts and specialists. Most of its work is done without the help of outside experts. FDA’s budget in 2012 totaled $4.36 billion [24] and is expected to be about $4.7 billion in 2014 [25]. FDA is comprised of designated Centers with responsibility for regulating each of the major health product areas—drugs, biologics, and devices—as well as dietary supplements and food/nutrition.

Therapeutic Product Jurisdiction

The Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) is most likely to regulate the early clinical research of most readers, but the Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER), the Center for Food Safety and Nutrition (CFSAN), and the Center for Devices and Radiologic Health (CDRH) could also be involved. A product application will be assigned to the appropriate Center for review, but may be reviewed in some circumstances by more than one Center. For example, a dermal patch that delivers insulin would be reviewed by both CDER and CDRH. Some products may be more difficult to assign. For example, a gel that swells in the stomach to result in weight loss could be considered a medical device instead of a drug, but a nonabsorbed resin that binds cholesterol and bile acids would be considered a drug. Dietary supplements, regulated by CFSAN, are by definition used by consumers without physician supervision and can make no disease treatment claims. Supplements are required to have evidence of only safety and good manufacturing quality. Supporting data are not reviewed prior to marketing and may not ever be reviewed. A widely used dietary supplement becomes a drug under CDER review when it is being investigated for a disease treatment or prevention. However, parallel development of a product as a dietary supplement and drug product rarely occurs. Once a supplement is commercially available, there is less likelihood that any further investment will be made in studies for disease treatment or prevention. Typically, a strategic decision is made early in the developmental pathway to follow a supplement route or a drug route, since these routes are very different in both cost and time to market. The exception to this is omega-3 products derived from fish oil. Omega-3 products are available as dietary supplements [labeled as supporting heart, eye and bone health] and approved drug products [for treatment of severe hypertriglyceridemia]. Insulin and other smaller peptide hormones are considered drugs and approved by New Drug Applications (NDA). Monoclonal antibody products are now regulated by CDER, but are approved by Biologics Licensing Applications (BLAs). Some other products—cell and gene therapies and some therapeutic vaccines—are licensed by BLAs, but reviewed by CBER. Combinations of products, including drug-device, drug-drug, and drug-supplement, may be regulated by two or, conceivably, three FDA Centers. For example, a diabetic wound-healing drug that is applied in a synthetic matrix would be jointly reviewed by CDER and CDRH. The same drug in a cellular matrix would be regulated by CDER and CBER.

It is relevant here to mention perhaps the quirkiest regulatory pathway in all of FDA—that of the medical food, which is regulated by CFSAN. This route is often raised as an attractive commercialization approach since it does not involve an IND and premarket review and approval. Medical food products must have a food-like quality that addresses a nutritional deficiency or gastrointestinal condition. Specifically, FDA’s definition is “a food which is formulated to be consumed or administered enterally under the supervision of a physician and which is intended for the specific dietary management of a disease or condition for which distinctive nutritional requirements, based on recognized scientific principles, are established by medical evaluation” [26]. These products can be studied without IND review [27], and they can have medical claims for treatment of disease. Ironically, the original law establishing the definition of medical food is the Orphan Drug Act, in part because some of the first medical foods were used for treatment of rare disease and inborn errors of metabolism. Recent modification to the FDA guidance for medical foods has made clear that a medical food is not a drug, nor need it be for an orphan indication. Furthermore, contrary to what has commonly been the case, a medical food label cannot bear an Rx symbol or “by prescription only” statement. Still, the product must be used under supervision of a physician [28]. This regulatory pathway is becoming more scrutinized by FDA as more dietary supplements and nonqualifying food products are sold as prescription products and/or for unaccepted indications.

The IND Review Process

The FD&C Act establishes that if an unapproved drug is used in the USA, it is considered misbranded and the marketer is therefore subject to prosecution. An exception to this requirement must be made for an experimental drug to be studied. FDA calls this an investigative new drug (IND) exemption. In common parlance, IND is used to refer to this exemption. FDA does not approve INDs or IND exemptions—it allows or issues them.

Pre-IND and Other Meetings with FDA

FDA’s role in the development of a new drug begins when the drug’s sponsor (an academic investigator, a manufacturer, or potential marketer) is preparing to conduct clinical studies in humans. CDER and CBER provide an option for a pre-IND meeting to provide advice in response to questions and preliminary data that the sponsor has compiled. CDRH provides a comparable pre-IDE (Investigation Device Exemption) meeting. Generally, for this meeting, the sponsor will present data to FDA that characterize efficacy and safety in animal models and that are sufficient to justify the anticipated initial exposure in humans. In some cases, the sponsor may have clinical data that have been produced in another country.

A request for a pre-IND meeting follows a standard outline and includes an initial draft of the questions that the sponsor wishes to have answered by FDA. In advance of the meeting, a briefing package of relevant data is submitted for review. If the meeting is granted, the divisions are generally required to provide preliminary written responses to the sponsor prior to the meeting or within about 30 days of submission of the briefing package. If the meeting is not granted, FDA will provided written comments. DMEP is among the busiest CDER review divisions and grants face-to-face pre-IND meetings less often, but does provide detailed written responses to submitted questions. The pre-IND meeting as the first interaction between the FDA and the sponsor sets the tone for an ongoing working relationship. Therefore, careful and thoughtful preparation of questions, background material, and proposed product development plan is essential. After receiving final written responses or FDA meeting minutes, the sponsor may engage in some limited written exchanges.

The less well-known “End of Phase 2A (EOP2A)” meeting is now also provided by CDER, but infrequently held [29]. This meeting can be of value for early clinical programs to gain feedback from FDA on clinical pharmacology issues. As described in the FDA guidance,

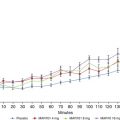

The overall purpose of an EOP2A meeting is to discuss options for trial designs, modeling strategies, and clinical trial simulation scenarios to improve the quantification of the exposure-response information from early drug development. The goal of these meetings is to optimize dose selection for subsequent trials to improve the efficiency of drug development. The exposure-response data discussed might be pertinent to evaluation of efficacy outcomes or adverse outcomes. In addition, the meetings would provide opportunities for discussions of complex issues pertaining to drug interactions, trials in special populations defined by genetic characteristics or other biomarkers, and other PK or PK/PD relationships.

In addition to the pre-IND meeting, FDA regulations provide two other formal meetings: the end of phase 2 (EOP2) meeting and the pre-NDA meeting. These are extremely important and valued landmark meetings for drug products in later-stage development, but are only mentioned here. The FDA guidance on formal meetings provides useful information [30].

The specific objectives of the EOP2A meeting are “to help select the dosing regimens for the next phase (typically phases 2 and 3) of drug development and to design informative dose-response trials that will inform later phase clinical trials by best incorporating prior quantitative knowledge.”

In cases in which two or more treatment indications are sought by the sponsor, and these come under the purview of different divisions, the sponsor can request separate pre-IND meetings with more than one division. In other cases, representatives from another division can be requested to address a specific issue involving the consulting division’s expertise. For example, a meeting involving a diabetes or obesity drug with potential for causing depression could benefit from participation from the Division of Psychiatry Products to discuss early evaluation of mood alteration as a safety issue.

Varieties of INDs

FDA provides two major categories of INDs and several less well-known specialized forms.

1.

The investigator IND is submitted by a physician or a qualified nonphysician investigator with the participation of a responsible physician to conduct a clinical trial in humans. The physician conceives, designs, and conducts the investigation and is responsible for directing how the investigational drug is administered or dispensed. The physician sponsor is also ultimately responsible for meeting all IND requirements, including supervision of study personnel, handling and analysis of data, reporting of adverse events, and annual IND reports. These responsibilities may be delegated to others. Investigator-sponsored INDs are typically used to explore the potential of a new molecule or metabolite or to evaluate a hypothesis involving an approved drug for a different indication or new patient population. FDA has traditionally been more flexible in its review and requirements for investigator INDs, but there is no formal difference in requirements for investigator- and commercial-sponsored INDs.

2.

A commercial IND is typically sponsored and owned by a company or research organization, though an individual (including, rarely, a physician investigator) could be the sponsor. The intent of the commercial IND is to develop a new molecule for approval or to develop an approved drug for a new indication, formulation, route of administration, patient population, and/or combination with another drug. All of the responsibilities described above and some others pertain to a commercial IND.

3.

An emergency use IND involves the authorization of an experimental drug to be used in an emergency situation (life-threatening or severely debilitating disease) that does not allow time for submission of a conventional IND. This provision is generally reserved for exceptional circumstances in which a very serious condition is involved and approved options have been exhausted.

4.

The treatment IND is rarely used, particularly in the metabolic area. FDA provides this option for an experimental drug that shows significant efficacy in late-stage clinical trials. It enables a treatment of serious or immediately life-threatening condition to be used more widely prior to final FDA review and approval. The sponsor may also be allowed to charge for the product under the treatment IND prior to FDA clearance for marketing. This regulatory provision is an option only after pivotal phase 3 clinical trials have been started.

5.

The exploratory IND [31] is a relatively recent provision aimed at streamlining the identification of lead molecules for further development. FDA describes in its guidance some additional flexibility and discretion in what is required to conduct a clinical study under an exploratory IND. Such a study is always conducted in phase 1, involves very limited human exposure, and has no therapeutic or diagnostic intent. The exploratory IND may be used to screen a number of related compounds or investigate the pharmacokinetics resulting from a “microdose” exposure. Because very small exposures are involved, FDA may waive or modify some of the nonclinical or product manufacturing requirements.

When an IND Is Not Needed

FDA has issued a guidance about when an IND is not required [32]. An IND is not required under two major circumstances—investigation of a marketed drug and bioequivalence studies of a marketed drug product and a generic version. A clinical study of a marketed drug is exempt from IND requirements if all of the following criteria are met:

The drug product is lawfully marketed in the USA.

The investigation is not intended to be reported to FDA as a well-controlled study in support of a new indication, and there is no intent to use it to support any other significant change in the labeling of the drug.

The investigation is not intended to support a significant change in the advertising for the drug.

The investigation does not involve a new route of administration, dose, patient population, or other factor that significantly increases the risk (or decreases the acceptability of the risk) associated with the use of the drug product.

When all of these criteria apply, not only is the IND requirement waived, but review divisions are also directed to decline such IND submissions even if the sponsor would like to have an IND.

Dietary supplements intended only to affect the structure or function of the body and not intended for a therapeutic purpose are not considered drugs by FDA. Products that are not drugs, such as foods or dietary supplements, do not require an IND. Exceptions include when a health claim is being sought for a food or a therapeutic or diagnostic use is being sought for a dietary supplement. For example, a study designed to evaluate whether vitamin D may reduce the risk of diabetes may require an IND since no health claim for this substance-disease relationship has been issued.

Content of the IND Submission

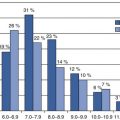

The required content of INDs is detailed in its rather old (but largely still current) guidance [33]. Additional details and updates are found in specialized guidances that have been more recently issued. One of the most significant recent changes to the IND has been in the format required for submission. As mentioned under the ICH section, the CTD (Common Technical Document) format is now being implemented as the required format for all IND submissions. In summary, the IND must contain information from the following three categories:

1.

Nonclinical data, including animal pharmacology, toxicology, and in vitro studies. These are required to support the safety of human subjects in the initial proposed clinical study. In summary, two toxicology studies—one in a rodent and one in a non-rodent species—of equal or greater duration to the proposed clinical study are required along with specialized animal safety studies. Animal studies that support the mechanism and targeted efficacy are desirable. In vitro studies include hERG, drug metabolism, and mutagenicity testing.

2.

Manufacturing and analytical information, including descriptions of the manufacturing process, identity, strength, quality, and purity of the drug substance and drug product, analytical procedures and specification, stability, consistency among batches, and container systems. These requirements are detailed in a number of guidances, but enumerated in the description of Current Good Manufacturing Practice for Finished Pharmaceuticals under 21 CFR Part 211:

(a)

General Provisions

(b)

Organization and Personnel

(c)

Buildings and Facilities

(d)

Equipment

(e)

Control of Components and Drug Product Containers and Closures

(f)

Production and Process Controls

(g)

Packaging and Labeling Controls

(h)

Holding and Distribution

(i)

Laboratory Controls

(j)

Records and Reports

(k)

Returned and Salvaged Drug Products

3.

Clinical protocols and investigator information, including one or more complete protocols, investigator brochure, any clinical data that may be available, qualifications of clinical investigators, and commitment to obtain informed consent from the research subjects, commitment to obtain review of the study by an institutional review board (IRB), and adherence to the investigational new drug regulations. The studies designed to be conducted in the following 12 months of the development plan should also be described so that FDA can offer suggestions or concerns that can be used to modify these plans.

IND Review Process

Once the IND is submitted, the sponsor must wait 30 calendar days before initiating the proposed clinical study. During this time, the primary chemistry, nonclinical, and clinical FDA reviewers will determine whether any substantial safety issues are involved. The reviewers usually provide concerns and recommendations, and they may also ask for further information from the sponsor. The primary goal of IND review is to assure that research subjects will not be exposed to unreasonable risk. This determination is based on having sufficient data and information from the three major review areas—nonclinical, CMC (chemistry, manufacturing, and controls), and clinical—aimed first at assessment of safety and second at achievement of other objectives.

If there are significant deficiencies and/or concerns about study participant safety, FDA can place a proposed or ongoing phase 1 clinical trial on full or partial clinical hold or, in extreme cases, even terminate the IND. A partial clinical hold means that a study may go forward or continue, but with some restrictions on the study design and execution. In some cases of IND review, one study may be allowed, while another is placed on clinical hold. A clinical hold is never issued lightly by FDA, and for phase 1 studies is only done for reasons of safety. FDA may place a phase 2 or 3 study on clinical hold for a substantial design or other non-safety issue, in addition to safety concerns. FDA is required to work with the sponsor to resolve the clinical hold on a timely basis. The sponsor can request a meeting if necessary to resolve the concern.

Once the IND review has been completed and the IND [exemption] allowed, the sponsor may submit subsequent protocols. FDA does not have a 30-day wait requirement for subsequent protocols submitted to the IND file, though it is prudent to wait for any FDA feedback on the protocol before beginning a study. Additional clinical studies may require supplementary nonclinical data and completion and analysis of data from a preceding clinical study. Communication from FDA may be very limited during the execution of the early-stage development plan until the EOP2 meeting.

The regulations allow for a stepwise process of accruing and refining CMC information. The amount of information and data needed will increase from phase 1 through phase 3 of the program, depending on the proposed duration of the investigation, the dosage form, and the amount of information otherwise available. For example, although stability data are required in all phases of the IND to demonstrate that the new drug substance and drug product are within acceptable chemical and physical limits for the planned duration of the proposed clinical investigation, if very short-term tests are proposed, the supporting stability data can be correspondingly limited for supporting short-term use and extended in parallel to support longer clinical studies.

Ethical Review

FDA has devolved primary responsibility for ethical review of clinical studies to institutional review boards (IRB). These boards are often chartered within an academic institution or hospital to provide local ethical review, but boards may also be independent and review studies remotely. The responsibilities of IRBs and investigators/sponsors have grown to include financial interest disclosure, verification of adequate research facilities, and others. Details for these responsibilities are found on the FDA website [34].

FDA clinical reviewers take into account ethical considerations as part of the evaluation of submitted studies. It is not required that informed consent documents be submitted to the IND file, but reviewers have the option of requesting the consent document. An ethical concern with a protocol can be a basis for a clinical hold.

Special Regulatory Programs

Early-phase investigators should be aware of special regulatory provisions and their potential relevance to studies that are done in phases 1 and 2.

Orphan Drug Program

The Orphan Drug Program at FDA has catalyzed the development and commercialization of high market value metabolic products including growth hormone and β-glucocerebrosidase (Cerezyme®), which is among the most expensive drug products now on the market [35]. The Orphan Drug Program was designed to encourage development of therapies aimed at small patient populations, which were originally neglected by the pharmaceutical community, but many orphan drugs have developed high market values after achieving FDA approval with relatively fewer clinical studies [36]. Market values for smaller Abundant information about the Orphan Drug Program is available on the FDA website [37–39]. When an orphan indication is targeted, the provisions of the Orphan Drug Act can provide a number of benefits, including grants for clinical investigation. Of relevance to the early investigator is the fact that today’s reviewers at FDA’s Office of Orphan Products are increasingly looking for more clinical evidence of a drug’s promise for treating the orphan condition than has been the case in the past. Before, emphasis was primarily put on insuring that the prevalence of the condition was below 200,000 people in the USA. Results from an early PK/PD study could be decisive in winning an orphan designation [40]. As mentioned above, orphan therapies have been approved in the broader metabolic area. It should be borne in mind that even for common conditions like diabetes, an orphan indication could be developed for a rare form of diabetes that has a well-understood genetic basis, is identifiable, affects fewer than 200,000 people in the USA, and is responsive to the therapy.

Such an example is FDA’s February 2014 approval of metreleptin (MyaleptTM, Bristol-Myers Squibb) as replacement therapy to treat the complications of leptin deficiency in patients with congenital generalized or acquired generalized lipodystrophy [41]. Metreleptin, a synthetic analog of the hormone leptin, had originally been envisioned as a therapy for obesity and type 2 diabetes. The drug’s value in improving the metabolic control in patients with the orphan condition of congenital generalized or acquired generalized lipodystrophy was demonstrated in a 3-year study organized by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases at the National Institutes of Health. Metreleptin treatment resulted in substantial improvements in both glycemic control and triglyceride levels [42]. Given the orphan indication, FDA’s approval was based on a relatively very small clinical development program.

Europe has a comparable orphan disease program, and FDA and EMA have created a common format for applying for orphan status with both agencies [43].

Fast Track and Breakthrough Therapy Programs

FDA has created several programs for speeding the development of drug and biologics therapies. These are explained in more detail on the FDA website [44]. Fast Track status and Breakthrough Therapy Designation are both available to products that show promise for meeting serious unmet clinical need. Generally, some clinical efficacy data are required for consideration. The FDA review divisions vary significantly in their willingness to consider and grant Fast Track status. DMEP has been among the most parsimonious divisions in granting Fast Track status.

Key Regulatory-Related Considerations in the Design and Conduct of Early Metabolic Studies

Therapeutic Indications

When filing for an IND (investigator or commercial sponsored), it is necessary to specify a therapeutic indication. Specifying the indication is even more important for a commercial IND. The stated indication is used for assigning the IND to the appropriate division. For a conventional diabetes or lipid-lowering treatment indication, the review division selection is straightforward. All such indications go to the Division of Metabolism and Endocrinology Products (DMEP). Diabetic complication indications go instead to the division that focuses on the affected organ system. See Table 12.1 for these assignments. The table also provides descriptions of the wording of approved therapeutic indications, the primary efficacy endpoint currently accepted by FDA, and some examples of approved products. As will be discussed below, the primary efficacy endpoint for regulatory approval is of importance to the earliest studies even if it cannot be measured until later studies. To a large extent, the approved therapies define minimal efficacy targets for newer therapies. Pressure is increasingly added to early studies to provide some efficacy data that will allow an estimate of the relative treatment effect on the regulatory endpoint.

Table 12.1

Approved therapeutic indications and regulatory endpoints for metabolic diseases

Indication | Phrasing | Primary efficacy endpoint | Approved therapies | FDA review division |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Type 2 diabetes treatment | Improve glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes | HbA1c | Many oral and injected products | DMEP |

Insulin products for type 1 and type 2 diabetes | Treatment of patients with diabetes mellitus for the control of hyperglycaemia | HbA1c | Many injected products | DMEP |

Inhaled insulin | ||||

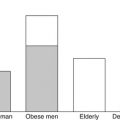

Weight loss | Chronic weight management in adults with an initial BMI of 30 kg/m2 without and 27 kg/m2 with the presence of at least one weight-related comorbidity | Body weight—continuous and categorical variables | Qsymia® (phentermine/topiramate) | DMEP

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|