Fig. 9.1

Anatomic boundaries and esthetic subunits of the lip

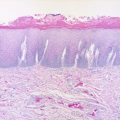

The new vermilion created by mucosal advancement may display a darker red color than that of the opposite vermilion, which can impart a feminine appearance and be a concern for men. Moreover, as the vermilion border is pulled posteriorly by wound contraction, adjacent whisker hairs may begin to turn up slightly and become a source of irritation to the opposing lip. This may require secondary repositioning of the vermilion border of the reconstructed lip. Some notching of the vermilion at the junction between the native vermilion and the advanced mucosa may occur with this technique, which may require a secondary V-Y advancement revision (Fig. 9.2).

Fig. 9.2

(a) Significant leukoplakia of the lower lip vermilion. (b) Vermilionectomy. (c) Mucosal Advancement. Two small V-excisions with primary closure were also performed laterally for skin lesions. (d) Postoperative picture after 6 months

A bipedicled mucosal flap is created as a linear band of mucosa, raised from the region immediately posterior to the wet line of the opposite lip to the defect (Fig. 9.3). The width of the band is determined by the width of the vermilion defect. The mucosal flap is undermined superficial to the orbicularis oris. If a bulk of tissue is needed, some orbicularis oris muscle and the labial artery may be included in the flap. The flap is then transferred to the opposite lip defect and sutured in place. The donor site is primarily closed. Division of the pedicle and flap inset is performed 2–3 weeks later as a second-stage procedure. Patient compliance during the healing phase is essential to the success of the flap.

Fig. 9.3

V-Y mucosal advancement flap used to repair small vermilion deficiency

An anterior tongue flap is usually harvested with the base of the flap on the dorsum of the tongue for lower lip defects and with the base on the ventral tongue for upper lip defects (Fig. 9.4). The flap is undermined superficial to the tongue musculature, and the leading edge of the flap is then sutured to the anterior margin of the vermilion defect. The flap inset and division of the pedicle takes place 2–3 weeks later as a second-stage procedure. The flap donor site can be closed primarily or allowed to heal secondarily, while the pedicle of the flap remains attached to the recipient lip. The anterior tongue flap satisfactorily preserves a natural lip pout and fullness but is uncomfortable and awkward for the patient while attached to the lip.

Fig. 9.4

(a) Lower lip vermilion defect and incision design for bipedicled labial mucosal flap. (b) Flap transferred to lower lip vermilion defect and primary repair of the donor site performed. (c) Pedicles divided and flap inset

9.4 Reconstruction of Full-Thickness Vermilion Defects

A full-thickness defect limited to less than one-third the width of the vermilion and the underlying orbicularis muscle can be closed by creating an advancement flap from the remaining vermilion (Fig. 9.5). A full-thickness incision is made along the vermilion border incorporating the labial artery in the flap. The vermilion portion of the orbicularis oris muscle is also included in the flap. The length of the incision must be kept sufficient to allow for adequate stretch of the flap to cover the entire defect.

Fig. 9.5

(a) Lower lip vermilion defect and incision design for dorsal tongue flap. (b) Inferior margin of tongue donor site sutured to inner margin of lip defect. (c) Superior margin of tongue flap sutured to outer margin of lip defect. (d) Pedicle divided and flap inset

Defects greater than one-third the width of the vermilion can be closed using a single pedicle cross-lip vermilion flap (Fig. 9.6) or a bipedicled vermilion flap from the opposite lip. This flap is based on the axial blood supply from the labial artery and is performed in the similar manner to the bipedicled mucosal flap described above except the orbicularis muscle and labial artery are incorporated into the flap.

Fig. 9.6

(a) Full-thickness vermilion defect less than 1/3 of the lower lip. Full-thickness vermilion advancement flap incised. (b) Vermilion flap advanced and inset

9.5 Reconstruction of Cutaneous Defects (Partial-Thickness Lip Defects)

Partial-thickness cutaneous defects of the lips occur more commonly in the upper lip than in the lower lip due to the higher prevalence of basal cell carcinoma in the upper lip region. The principles of reconstruction for partial-thickness lip defects are similar to those for other facial subunits. Strict attention to the relaxed skin tension lines (RSTLs) and the borders of the lip and perioral subunits are paramount to an esthetic outcome. The RSTLs for the lips course in a radiant fashion around the mouth and reflect the perioral rhytids of older patients. These lines are oriented perpendicular to the underlying orbicularis oris fibers. The borders of the lip subunits include the nasolabial creases, nasal sill, alar bases, philtral columns, vermilion borders, and labiomental crease. Incisions that are placed parallel to or along the RSTLs and borders of the esthetic subunits are less conspicuous than those placed perpendicular to these lines. Moreover, it is preferable to confine tissue transfer within the esthetic region of the lips, unless this causes excessive distortion of surrounding structures such as the nasolabial crease.

The reconstructive ladder gives a useful framework that stratifies options by level of complexity and includes primary closure, healing by secondary intention, skin grafting, local flaps, regional flaps, and microvascular free flap. There are no absolute indications for a particular reconstructive method, and preferences vary by individual surgeon and geographic regions. Microvascular free flaps are usually reserved for a massive composite defect and are rarely used for partial-thickness cutaneous defects and are discussed in detail elsewhere in the textbook and later in this chapter.

Some small cutaneous defects along the nasolabial crease away from the lip vermilion may be left to heal by secondary intention. Wounds near the lip or large defects may exhibit excessive wound contraction and distortion of the vermilion if led to heal by secondary intention. Skin grafts are used for small defects only when local flap reconstruction is not readily available. The lip is a relatively mobile tissue, necessitating proper immobilization of skin grafts for successful take. Preferred skin donor sites include the supraclavicular region and the postauricular region due to their good color match with the facial skin. Full-thickness skin grafts are preferred over split-thickness skin grafts because of their better color match and lower tendency for secondary contracture [26].

Most surgeons prefer to reconstruct cutaneous lip defects by primary closure or with local flaps due to their superior esthetic results. Small cutaneous lesions can be excised in an elliptical fashion and closed primarily. The elliptical excision is oriented with its long axis along the anatomic subunit borders or the RSTLs of that region of the lip. A vertical closure extending beyond the vermilion border may contract and result in pull from the vermilion border. If possible, incisions for primary closure should stop before crossing the vermilion border using a W-plasty. Likewise, elliptical excisions should avoid extension beyond the nasolabial or mental crease lines using a W-plasty. A W-plasty may also reduce tissue redundancies, particularly near the free margin of the lip. Cutaneous defects near the vermilion border can also be closed in an A-T fashion, which entails creation of a triangular defect with its base along the cutaneous-vermilion junction for excision of a lesion. On both sides of the triangular defect, the incision is extended along the cutaneous-vermilion junction to develop two rotational flaps. The final T-shaped closure has favorable scars in RSTLs and along the anatomic subunit borders.

Local flaps offer a functional recovery, high success rate, and excellent esthetic outcomes for large size wounds not amenable to primary closure. Local flaps can be categorized into transpositional flaps, rotational flaps, and advancement flaps. In addition, Burow’s triangles can be incorporated into a flap design as needed to prevent a “dog-ear” deformity. In any local flap design, it is preferred to line up as many closure lines with the RSTLs or the anatomic subunit borders as possible.

9.6 Full Thickness Defects Less Than 30 % of the Lip

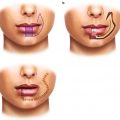

Simple excision of a small lip cancer often results in a full-thickness semicircular defect. As long as the defect is less than 30 % of the lip, it can be primarily closed without tension. However, this type of closure results in puckering or notching of the lip margin. Therefore, additional tissue should be trimmed to make the defect either “V”-shaped or pentagonal (Figs. 9.7 and 9.8). This method is similar to the excision of a circular lesion on a skin with an elliptical incision to facilitate closure without a “dog ear.” The orbicularis oris muscle on both sides of the defect must be sutured together in order to reestablish the continuity of the oral sphincter. After sturdy closure of the orbicularis oris muscle, the vermilion-cutaneous junctions on both sides are carefully reapproximated and sutured. The accuracy of this realignment is crucial to the esthetic outcome of the reconstruction. A “step-off” along the vermilion-cutaneous junction can be easily recognized as a flaw to human eyes. Some surgeons elect to tattoo the vermilion border or the white line before injection of local anesthetics with a tuberculin syringe and methylene blue because of tissue blanching and distortion [5]. The rest of the mucosa, vermilion, and skin of the chin are then closed. After closure of the wound, placement of steri-strips can minimize tension across the closure.

Fig. 9.7

(a) Upper lip vermilion defect and cross-lip vermilion flap. (b) Flap transferred and primary repair of the donor site. (c) Pedicle divided and flap inset

Fig. 9.8

(a) Direct closure of a circular defect of the lip results in puckering and bulging of tissue. (b) Conversion of this defect into a “V” results in a smoother, unpuckered closure. (c) V-excision design marked for a lower lip cancer. (d) Closure

When the defect is in the midline of the lip, the width of the vermilion on each side of the defect should be equal. However, because the vermilion tapers laterally, lateral defects usually have a mismatch in the vermilion width between two sides of the defect. This problem can be solved by making the incision along the lateral limb of the “V” in an oblique fashion, increasing the width of the lateral vermilion to match the wider medial vermilion (Fig. 9.9).

Fig. 9.9

(a) Pentagonal-wedge resection for lower lip defect less than 1/3. (b) Closure. (c) Postoperative picture after 2 months

For larger defects that extends further inferiorly on the lower lip, either a “W”-shaped excision or a shield-shaped excision may result in less tissue loss, permitting primary closure. Moreover, a “W” excision allows primary closure without violating the labiomental crease and chin subunit (Fig. 9.10).

Fig. 9.11

(a) A central excision permits closure of equal-sided edges. (b) Lateral excision results in a mismatch in vermilion width with a “step-off” due to tapering of the vermilion width laterally. (c) Oblique incision on the shorter side permits closure of equal-sided edges

When lip resections result in a rectangular defect, advancement flaps from the adjacent tissue can be performed with a primary closure (Fig. 9.11). Excision can be planned so that the base of the rectangle is placed along the mental crease or nasal sill for better esthetic results. Burow’s triangle excisions are usually necessary at the lateral limits to prevent “dog-ear deformities.” The orbicularis oris is reapproximated with resorbable sutures, recreating the complete ring of oral sphincter. The mucosal margins are reapproximated and sutured with resorbable sutures in an everted fashion to provide a watertight mucosal seal. The skin is closed with nylon or prolene sutures with meticulous realignment of the vermilion border (Fig. 9.12) [3].

Fig. 9.10

(a) W-excision. (b) Closure. (c) Postoperative picture after 3 months

Fig. 9.12

(a) A rectangular excision with a design of bilateral advancement flaps with Burow’s triangles. (b) Closure

9.7 Medium Full-Thickness Defects

Medium defects are defined as approximately 30–80 % of the vermilion width. Most of these defects are satisfactorily reconstructed by redistribution of the remaining lip tissue without any need for regional or distant flaps (Fig. 9.13).

9.7.1 Stair Step

Lower lip defects of 30–50 % can be successfully closed with the stair-step flap [8]. This technique brings adjacent tissue medially from the lateral chin and lip area to fill the lip defect. After the defect is squared off, successively smaller square-shaped defects are created diagonally in a stair fashion extending from the inferior line of the defect. A total of two to four steps are usually used. At the bottom of the “staircase,” a Burow’s triangle can be excised to allow smooth medial movement of the flap. The advanced flap is meticulously closed in a layered fashion. Bilateral flaps can be used for defects greater than 2 cm or for midline defects for symmetry (Fig. 9.14).

Fig. 9.13

(a) Lesion of the upper lip. (b) Excision of the whole lateral subunit. (c) Bilateral advancement flaps designed. (d) Elevation of the flaps. (e) Reapproximation. (f) Closure. (g) Postoperative picture after 6 weeks

This technique restores the complete ring of the orbicularis oris for a functional oral sphincter. The stepwise closure redistributes and spreads the tension on the wound to a broader area and prevents significant scar-contracture problems. Moreover, this flap does not require incisions on the upper lip, avoiding the more cosmetically noticeable upper lip scar [3].

9.7.2 Lip Switch

A lip-switch technique utilizes a temporarily pedicled flap from one lip for reconstruction of a full-thickness defect of the opposite lip. Although it can be used for defects greater than 50 % of one lip, functional and esthetic outcomes are better in 30–50 % defects. Three most commonly used lip-switch techniques are Abbe, Estlander, and Stein, each with different indications.

The Estlander flap was described in 1872 where pericommissural defects were reconstructed by the flaps from the opposite lip (Fig. 9.15). For defects of the lateral lip involving the commissure, tissue from the ipsilateral part of the opposite lip is rotated around the corner of the mouth as a pivot point into the defect. This flap is based on the medial mucosal bridge and the labial artery. According to Estlander’s clinical measurement during the operations and cadaver dissections, the distance of the artery from the mucosa was almost constantly 2 mm, while the distance from the skin varied widely depending on the thickness of the lip. Also, the vertical distance of the artery from the lip margin varied widely, closer to the margin in the middle of the lip than at the commissure. Thus, the surgeon should be guided by the clinical exam while bluntly dissecting when trying to preserve the labial artery for the axial pattern of this flap. It has also been reported that the mucosal bridge up to 1 cm is essential to the survival of the flap, more so than the labial artery [4]. The rotated flap is meticulously closed in a layered fashion with alignment of the orbicularis oris and the vermilion-cutaneous junction [10].

Fig. 9.14

Bilateral stair-step advancement flaps. (a) A lower lip lesion and the stair-step design. (b) Excision of the lesion. (c) Elevation of the flaps. (d) Closure

The concept of the Estlander flap was extended to the reconstruction of the central defect of the lips in the Abbe flap technique. The Abbe flap, when first described in 1898, used tissue from the middle of the lower lip to reconstruct the philtral unit of the upper lip for a patient with a deformity from bilateral cleft lip repair (Fig. 9.16) but is well suited for both upper and lower lip reconstructions. When reconstructing the upper lip, both the central and lateral lower lip can serve as a donor site. However, when the upper lip is used as donor tissue, the philtrum is preserved for the delicate esthetic balance of the central upper lip and, thus, the lateral upper lip is used as donor tissue more commonly.

Fig. 9.15

(a) Estlander flap for a lower lip defect. (b) Closure after the Estlander flap

After removal of a lesion, the defect is trimmed to a shape of a triangle or half ellipse. A same-shaped flap is designed on the opposite lip to be half as wide as the defect for balanced upper and lower lip lengths after flap transposition. The flap is then elevated, much like the Estlander flap, based on the labial artery and mucosal tissue. This flap is rotated around this mucosal bridge and labial artery as a pivot point into the defect and closed in a layered fashion with meticulous alignment of the orbicularis oris and the vermilion-cutaneous junction. Flap division is performed with realignment of the vermilion borders at 2–3 weeks [1].

The Stein flap was developed in 1848 to preserve the philtral subunit of the upper lip while reconstructing a central lower lip defect with two upper lip flaps (Fig. 9.16). The Stein uses two small symmetric flaps from the periphiltral region for reconstruction of a midline lower lip defect. Two same-sized full-thickness flaps are raised symmetrically in the upper lip at an equal distance lateral to the philtrum. This technique preserves symmetry of the upper lip and causes less tissue distortion than the Abbe flap technique. The Stein flap is based on the superior labial artery and mucosal bridge. These flaps are rotated into the lower lip defect and closed meticulously in a layered fashion with alignment of the orbicularis oris and the vermilion-cutaneous junction (Fig. 9.17). Flap division is performed with realignment of the vermilion borders at 2–3 weeks [3].

Fig. 9.16

Abbe flap for a philtral defect

A major advantage of the lip switch techniques is the use of similar local tissue for reconstruction of lost tissue. Compared with borrowing tissue from distant sites, this technique gives better esthetic and functional outcomes. The continuity of the orbicularis oris is restored by sturdy closure of the muscle. Although transplanted flaps are initially paralyzed and anesthetic, most of them become reinnervated with both motor and sensory functions within 1 year, providing excellent long-term functional results [3].

The Abbe flap is a useful option for revising lip reconstructions as a secondary lip-balancing procedure. If there is a relative deficiency in lip length after performance of a circumoral lip reconstruction (e.g., after Gillies fan flap), an Abbe flap can be transposed to the shortened lip from the opposite lip restoring balance [2].

The esthetic outcome depends heavily on patient factors. An elderly patient with a large oral aperture and redundant tissue may not have significant asymmetry after harvesting of a lateral upper lip flap, while a young patient with a relatively small mouth and shallow nasolabial folds can have a marked deformity from harvesting of the same flap. The Stein flap is one lip-switch technique designed to avoid upper lip asymmetry when reconstructing the lower lip defect, but it can potentially leave unattractive scars in the central portion of the upper lip [3]. Lastly, both Abbe flap and Stein flap are two-stage procedures that require division of the pedicle 2–3 weeks after the initial procedure. Although the second surgery can be usually done under local anesthesia in the office setting, it requires strict patient compliance in terms of keeping the pedicle intact. The advantages and disadvantages of each lip-switch flap must be considered individually for each patient and also weighed against other reconstructive alternatives.

9.7.3 Zisser Flap Technique

The Zisser technique was introduced in 1975 for large commissure defects. It is ideal for defects involving an area of full-thickness cheek and commissure as well as both upper and lower lips (Fig. 9.18). The Abbe and Karapandzic flaps are not suitable in these situations due to their inability to repair both lips simultaneously. The basic design of the technique includes two triangles above and below a defect with medial limbs along the nasolabial folds, allowing for advancement and recreation of the folds during reconstruction. The overall design is crescent-shaped. The triangles are resected through skin, subcutaneous tissue, and muscle, down to the mucosa. Lateral to the defect, a full-thickness horizontal incision is made at the same level as the commissure. Two small triangular areas of tissue above and below the horizontal incision are deepithelialized. The lateral cheek tissues are then advanced medially into the defect, and the buccal mucosa above and below the horizontal incision in the deepithelialized area is advanced to the new vermilion border. The wounds are then closed in a layered fashion taking care to realign the orbicularis oris muscle and the vermilion-cutaneous junction [8].

Fig. 9.17

Stein flap for a midline lower lip defect

The Zisser flap does not result in a “rounded” commissure obviating the need for secondary commissuroplasty and may be a good alternative to the Estlander flap in some situations.

9.7.4 Gillies Fan Flap (Rotation-Advancement Nasolabial Flap)

The Gilles fan flap transfers tissue around the commissure, using the opposite lip and cheek tissue based on the labial artery for reconstruction of a lateral lip defect. In comparison with the Estlander lip-switch flap, a larger amount of cheek tissue moves with the fan flap, and the fan-shaped design of the flap permits its closure in one continuous line [3]. The Gillies fan flap can be used bilaterally to reconstruct large full-thickness defects of the central lip (Fig. 9.19).

Fig. 9.18

Zisser flap technique. (a) Oral commissure lesion. (b) Defect after resection. (c) Creation of superior and inferior triangles around defect. (d) Closure of defect with advancement of cheek. Note the Zisser flap incisions performed through the skin, subcutaneous tissue, and muscle to the level of the mucosa in the superior and inferior triangles. The posterolateral aspect of the resection is deepithelialized and advanced anteriorly to become the new commissure

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree