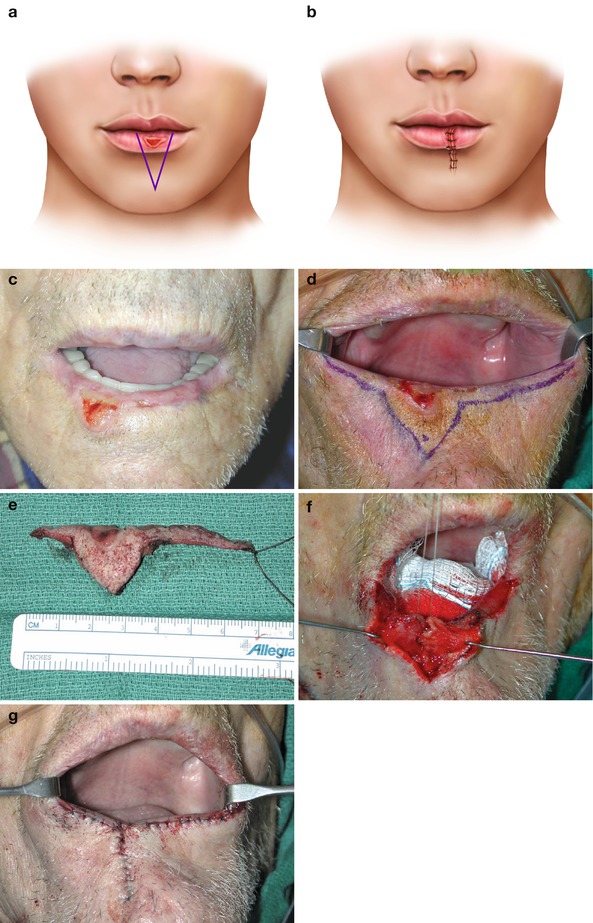

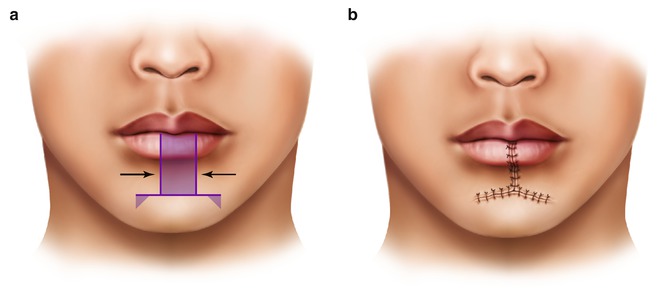

Fig. 8.1

(a) Vermilionectomy. The incision for the vermilionectomy is marked out from the vermilion border anteriorly, to the wet-dry line posteriorly. (b) The vermilion is excised in a submucosal plane. (c) Resected vermilion specimen, which is marked with a silk suture for orientation. (d) The lip mucosa may be undermined in a submucosal plane (between the submucosa and orbicularis oris muscle). The mucusa is advanced anteriorly and sutured to the skin with interrupted 5-0 prolene suture, which are later removed after one week

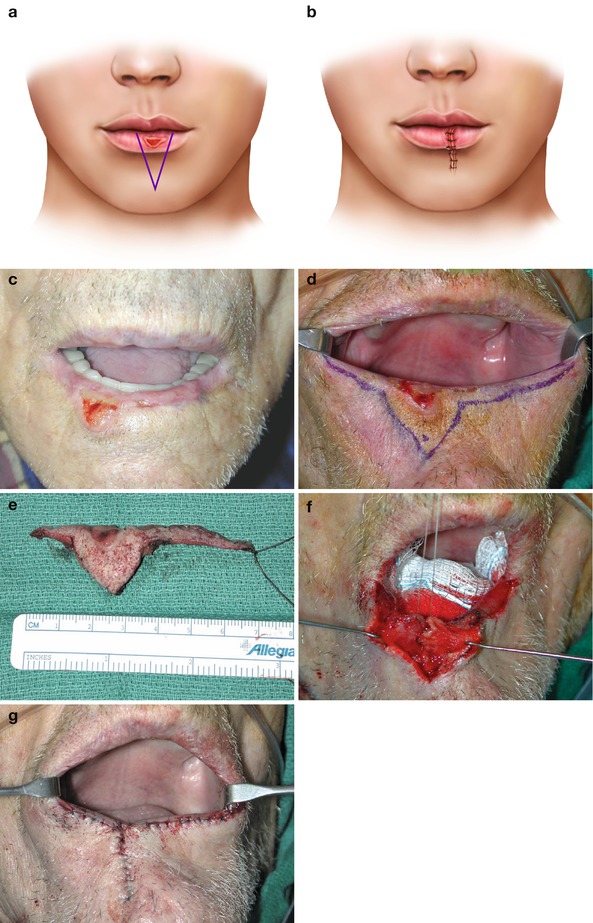

The V-wedge excision is the simplest type of excision and can be used for the upper or lower lip. Classically, it is described that defects of up to one-quarter of the upper lip and one-third of the lower lip can be closed primarily [1, 2, 5]. While this may be the case, reconstructing the upper lip is not as straightforward as it is for the lower lip. Because the upper lip is made up of three esthetic subunits (philtrum and two lateral segments), a wedge excision will cause asymmetry of the lip. The lower lip, on the other hand, is composed primarily of one esthetic subunit and will tolerate a wedge resection without much distortion. A wedge resection that is acceptable for a lower lip lesion may cause significant asymmetry of the upper lip, and in these cases, a lip-switch procedure, such as an Abbe flap (described later), may produce a superior cosmetic result [2].

The V-wedge procedure begins with marking out oncologically safe resection margins on either side of the lesion (Fig. 8.2) [5, 12, 13]. The apex of the excision lies at the labiomental crease of the lower lip or nasolabial fold of the upper lip. The full thickness of the lip is incised to resect the lesion, and the defect is closed primarily in at least three layers, with care taken to re-approximate the orbicularis oris muscle. The vermilion border must be lined up precisely for acceptable cosmesis. Irregularity of the vermilion border by as little as 1 mm may be noticed by an observer at speaking distance.

Fig. 8.2

(a) V-excision. Proposed resection with apex of triangle located at labiomental crease. (b) Final reconstruction which leaves a vertically oriented linear scar. (c) Squamous cell carcinoma of lower lip with actinic changes of remainder of lip vermilion. (d) Excision margins are marked out with a vermilionectomy incorporated into the resection. (e) Excised specimen with suture marking orientation. (f) The orbicularis oris muscle is reapproximated primarily with 3-0 vicryl suture. (g) The reconstruction is completed by reapproximating the skin and lip mucosa, and then advancing the lip mucosa anteriorly to the skin edge

As its name implies, the W-excision is a full-thickness resection in the shape of a “W.” [12, 13] The advantage of the W-excision over the V-excision is that it allows the vertical arms of the excision to be shorter to avoid crossing the labiomental crease, and thus can be used for wider lesions than the V-excision (Fig. 8.3). As such, it is used primarily for lower lip lesions. Closure of the defect is in the same three-layered fashion as the V-excision; however, the wound is re-approximated in such a way as to convert the scar into an upside down “Y.”

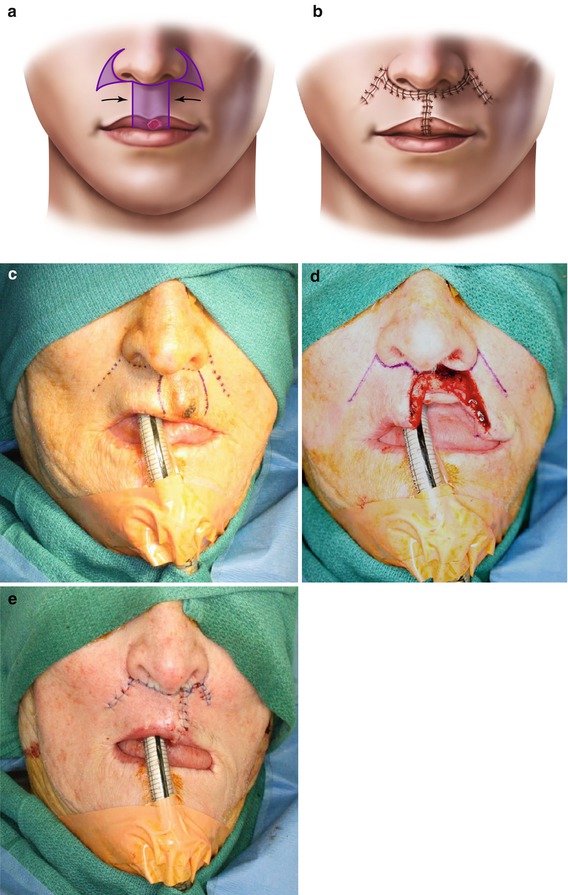

Fig. 8.3

(a) W-excision. Proposed resection with apices of W located at labiomental crease. (b) Final reconstruction which leaves a Y-shaped scar. This type of excision is useful for larger lesions since it allows for a wider resection without extending the incision as far inferiorly as would be required for a V-excision. (c) The incision is marked out. A vermilionectomy is incorporated into the resection. (d) Completed resection, which produced a full-thickness defect. (e) The orbicularis oris muscle is reapproximated first, followed by primary closure of the skin and mucosa. The lip mucosa is then advanced anteriorly to the skin edge. (f) Healed wound. Note the new lower lip “vermilion” is thinned due to scar contracture and the inward rolling of the lower lip skin

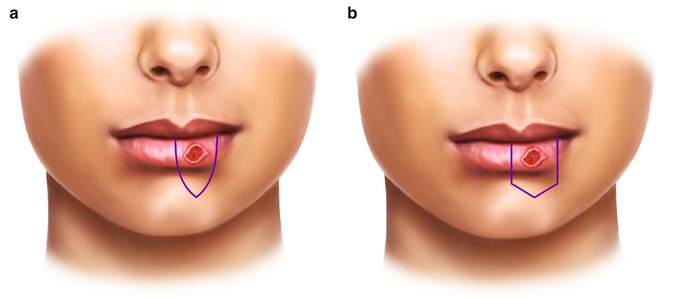

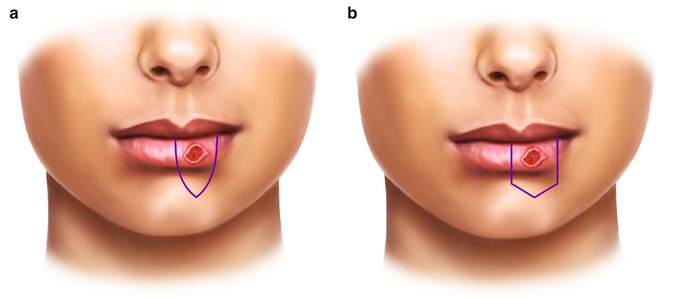

The shield and pentagonal excisions are similar in shape with two vertical arms on either side of the lesion which then turn towards each other in a curvilinear or angular fashion, respectively (Fig. 8.4) [3, 13]. The apex lies at the labiomental crease of the lower lip or nasolabial crease of the upper lip.

Fig. 8.4

(a) Shield excision. (b) Pentagonal excision

8.2.2 Lateral (Rectangular) Advancement Flaps

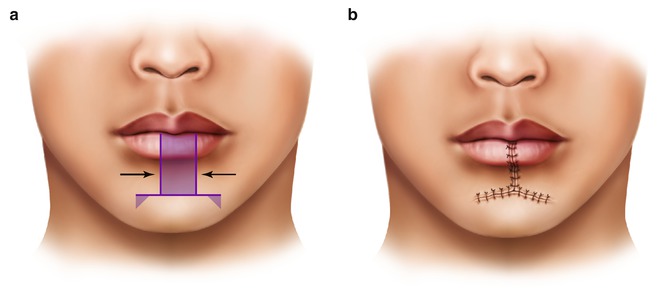

Lateral (rectangular) advancement flaps are full-thickness flaps that are useful for reconstructing lower lip defects [3]. They are not ideal for the upper lip because they will distort the philtral columns and lip symmetry. To perform this technique, the lesion is excised full-thickness in a rectangular fashion (Fig. 8.5). Horizontal full-thickness incisions are then made along the labiomental crease. Because of the elasticity of mucosa, the horizontal incisions do not need to be made as far laterally through the mucosa (full thickness) as they do for the skin and muscle (partial thickness). To aid in closure, partial-thickness Burow’s triangle excisions of skin and subcutaneous tissue are made at the ends of the horizontal incisions. The two flaps are advanced medially and closed primarily in three layers.

Fig. 8.5

(a) Lateral advancement flap. The lesion is excised in a full-thickness fashion and the wound edges are advanced medially. Burow’s triangles (of skin and subcutaneous tissue) may be incorporated into the resection to prevent bunching of the tissue during wound advancement and closure. (b) The wound is closed in three layers and results in a T-shaped scar

The T-excision is a rectangular advancement flap that is useful for the excision of a lesion of the central portion of the upper lip (philtrum) (Fig. 8.6) [2]. The horizontal full-thickness incisions are made below the nasal base, and the lateral lip flaps are advanced medially. Further advancement can be obtained with crescentic perialar excisions of skin and subcutaneous tissue as described by Webster [2, 5]. This allows advancement of lip as well as cheek tissue.

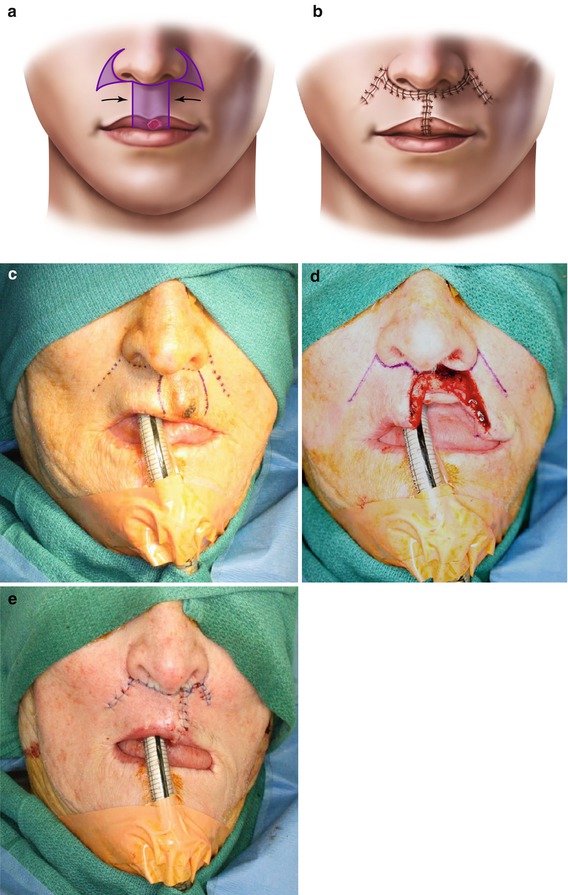

Fig. 8.6

(a) T-excision. The lesion is excised in a full-thickness fashion leaving a defect of the central upper lip. Partial-thickness perialar excisions of skin and subcutaneous tissue can be used to gain further advancement of the wound edges. (b) Resulting repair. Note that the philtrum and Cupid’s bow are lost. (c) Incisions are marked out. (d) The lesion is resected in a full-thickness fashion. To gain adequate mobility for the lateral tissue flaps, horizontal incisions are made under the nasal base and extended into the nasolabial creases. These horizontal incisions only need to be made in a full-thickness fashion such that they allow the mucosa to reapproximate. The incisions may then transition to partial-thickness more laterally, leaving the mucosa intact in these lateral-most areas. (e) Final reconstruction of defect. Perialar excisions were not needed for closure of this wound

8.3 Defects One-Third to Two-Thirds of the Lip

Moderately sized defects, measuring one-third to two-thirds of the lip, can be subdivided into those that involve one-third to one-half of the lip, and those that involve one-half to two-thirds of the lip.

8.3.1 One-Third to Two-Third Defects

8.3.1.1 Lip-Switch Flaps (Cross-Lip Flaps)

Lip-switch flaps use temporarily pedicled tissue from one lip to reconstruct a full-thickness defect of the opposite lip. The Abbe, Estlander, and Stein flaps are the three most commonly used versions of lip-switch flaps [3]. These flaps are based on the labial artery in the vermilion of the donor lip [4]. Venous drainage is provided by small veins that parallel the course of the artery [5]. The Abbe and Stein flaps are two-stage flaps, in which the vascular pedicle must be divided once independent vascularity has been established. While the pedicle is in place, the patient will have difficulty eating and must be careful not to disturb or traumatize this pedicle during the revascularization period. The pedicle is typically divided after 3 weeks from the first stage. This can be done in the office under local anesthesia. To test the viability of the flap before pedicle division, a piece of umbilical tape can be passed around the pedicle and twisted to occlude the blood supply. Immediate and profound blanching implies that adequate blood supply has not yet been developed and more time is needed before division. Once the pedicle is divided, the vermilion is inset on either lip.

Because lip-switch flaps involve the transfer of full-thickness lip tissue, there is restoration of the orbicularis oris muscle sphincter. While initially paralyzed and paresthetic, studies have shown that the muscle and skin regain innervation and therefore have a good functional result [1, 3, 5, 8].

All lip-switch flaps result in a smaller oral opening, but this is rarely a problem because they are rarely used for a defect of more than 30–50 % of the lip. Loss of 50 % of one lip only results in a 25 % decrease in the total oral circumference [3].

The Abbe (Sabbattini) flap, first described by Sabattini in 1836, and later by Abbe in 1898, involves the transfer of a triangular-shaped, full-thickness segment of one lip to the opposite lip (Fig. 8.7) [3–5, 16]. While the original description called for the transfer of lower lip tissue to reconstruct the upper lip, the Abbe flap can be used to reconstruct lower lip defects as well. Even so, they are most useful for reconstructing upper lip defects because tissue can be harvested from the lower lip without noticeably changing the symmetry of the donor lip [3]. Using the upper lip as donor tissue creates asymmetry in the more esthetically noticeable upper lip and may even remove the philtral column and Cupid’s bow.

Fig. 8.7

(a) Abbe flap. The full-thickness triangular excision of the upper lip is marked out, followed by the incision of the lower lip. The lower lip incision is also made in a full-thickness fashion, however it stops at the vermillion border to preserve the vascular pedicle, which is typically based medially. Here, the base of lower lip flap is made almost equal to the width of the defect to help preserve symmetry of the more conspicuous upper lip. The base can also be made smaller to “share” the tissue loss between both lips. This is more important when rotating upper lip flaps into lower lip defects. (b) The lower lip flap is then rotated superiorly and inset into the upper lip defect. The lower lip defect is closed primarily. (c) After three to four weeks of healing, the vermillion tissue pedicle is divided and inset

The Abbe flap may be pedicled medially or laterally, except for when the defect involves the more lateral portion of the lip, in which case the pedicle is based medially [5]. In all other circumstances, the location of the pedicle may be chosen to allow for easier flap transposition and inset. The height of the flap should equal the height of the defect and the axes should parallel the relaxed skin tension lines. The width of the base of the flap is usually made one-half of the width of the defect so that the sizes of the two lips remain proportionally similar after reconstruction. However, for upper lip defects that comprise an entire esthetic subunit, such as the philtrum or lateral segment, the donor flap width may equal the size of the defect to restore the complete esthetic subunit. Additionally, the shape of the flap may vary according to the shape of the defect it is reconstructing. Simple Abbe flaps are typically triangularly shaped but may be designed with a more complex geometry to reconstruct an entire esthetic subunit as described by Burget [6].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree