7 Recommendations for Structured Care

Introduction

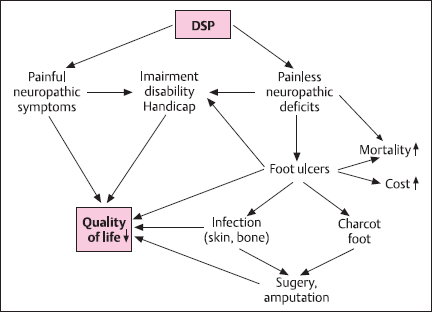

Diabetic neuropathy (DN) is as frequent as microvascular complications of diabetes mellitus. It includes manifestations in the somatic and autonomic parts of the peripheral nervous system [1,25]. Distal symmetric sensory or sensorimotor polyneuropathy (DSP) is the most important clinical manifestation, affecting approximately 30% of the hospital-based diabetic population and 20% of community-based samples of diabetic patients. DSP is related to both lower extremity impairments, such as diminished position sense, and functional limitations, such as walking ability [2]. Neuropathic symptoms are present in 15–20% of diabetic patients. 7.5% of whom experience chronic neuropathic pain [3]. Elevated vibration perception threshold predicts the development of neuropathic foot ulceration, one of the most common causes of hospital admission and lower limb amputation among diabetic patients [4] (Fig. 7.1). Autonomic neuropathy is similar in importance to DSP. There is accumulating evidence to suggest that markers of DN such as nerve conduction velocity, vibration perception threshold, and autonomic function tests predict mortality in diabetic patients [5.6].

Obviously the impact of DN on the quality of life and prognosis of the diabetic patient and its economic burden are important. However, while screening and monitoring of microangiopathies and macroangiopathy has become established as routine in diabetes care. DN is often neglected. Even the Saint Vincent Declaration of 1989 [7], which among other things has goals for prevention of amputations, myocardial infarction, and eye and kidney problems, and for improvement of fetal outcome in diabetic pregnancies, failed to consider DN. These deficiencies should urgently be corrected.

Fig. 7.1 Clinical impact of diabetic distal symmetric polyneuropathy (DSP)

Outpatient Diabetes Care

Competent diabetes management includes correction of the metabolic disorder as well as prevention and treatment of the chronic complications of diabetes.

Well-educated and well-trained, self-motivated subjects with diabetes should take care of themselves on a day-to-day basis. Nevertheless, these persons should also regularly consult their doctor and their diabetes team for metabolism monitoring, physical health check-up, teaching, and, if necessary, psychologic support.

For the majority of diabetic people outpatient care is in the hands of general practitioners. The American Diabetes Association [8] recommends daily contact for the initiation of insulin treatment or a change in regimen, weekly contact for initiation of oral diabetic therapy or a change in regimen, three-monthly routine visits for patients who are not meeting the goals, and six-monthly visits for other patients. For the aims of treatment see page 19–20. An annual physical examination is recommended, but previous abnormalities on physical examination should be checked up on at each regular diabetes-related visit. Patients with high risk foot conditions (see page 295–300) should be seen more often.

The European type 2 diabetes policy group guide of 1993 [9] made precise proposals for what to do at the initial visits and at quarterly and annual follow-up (Table 7.1). Recent updates of the European guidelines on type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus [10,11] allow for more individual schedules for both types of diabetes. There seems to be a consensus on the recommendation of an annual physical examination and on frequent follow-ups of previous abnormalities. Proper diabetes care requires close cooperation between patients, the diabetes care team, diabetologists, and specialists in various fields [12].

Table 7.1 Clinical monitoring protocola [9]

At initial visitb Complete history and examination: Weight, height (BMI; kg/m2) Blood pressure Search for neuropathy Foot inspection Fundoscopy (dilated pupils) or fundus photography and visual acuity Biochemical tests: Blood glucose HbA1, or HbA,1c Serum triglycerides, cholesterol, HDL cholesterol (calculate LDL cholesterol if possible) Plasma creatinine Urine glucose, urine protein, microalbuminuria, urine ketones Start teaching program Nutritional advice Start self-monitoring | At second visit Continue teaching program Weight Blood pressure Postprandial blood glucose Peripheral pulses Every 3 months Continue teaching program Weight Blood Pressure Postprandial blood glucose HbA1 or HbAlc Lipds ( if abnormal ) Urine protein and microalbuminuria (if previously abnormal) Foot inspection in those at risk (peripheral pulses and/or peripheral neuropathy) Annually Physical examination and biochemical tests as in Initial visit Re-evaluate treatment and nutritional program Check self-monitoring technique Refer to specialist if progress is unsatisfactory Continue teaching |

aData can usefully be recorded on the St. International Care Card

b Can be spread over more than one visit

c More frequently for poorly controlled patients

Screening and Early Detection of Diabetic Neuropathy

Screening should detect DN at an asymptomatic stage. Therefore, the patient cannot contribute much more than asking for appointments at the appropriate time.

Screening requires practicable methods that can be applied to a large number of people. Physical examination is necessary but not sufficient. The rational selection of additional tests is difficult, because DN is a very complex disorder. Among the sensorimotor neuropathies, distal polyneuropathy (DSP) is the most frequent, and the most common form of autonomic DN is cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy (CAN), but other clinical manifestations of sensorimotor and autonomic neuropathy may develop first. Measurement of nerve conduction velocity, vibration perception threshold, and pressure perception by monofilament and other methods have been used to screen for asymptomatic DSP, and measurement of heart rate variability (HRV) has been recommended for detection of asymptomatic autonomic neuropathy, but there is still no generally accepted consensus on the battery of tests which takes into consideration the selection of nerves and functions and the conditions for HRV tests. This lack of standards is an impediment to regular screening.

Another reason why screening for DN has so far nor been implemented in clinical routine is the lack of practicability. General practitioners will usually be unable to measure nerve conduction velocity. They could measure HRV, but determining HRV under different conditions “by hand” is time consuming and imperfect. With proper PC-based equipment it can easily be determined by technical assistants or even the doctors’ receptionists. However, the equipment and software are expensive, and for these reasons patients usually have to be referred to a diabetologist or neurologist.

Thus, either general practitioners must be enabled to practice existing screening methods or more practicable tests must be developed (see below).

Outpatient Care of Diabetic Neuropathy

Early detection of symptomatic neuropathy is an urgent aim of quality assurance today. The interval between annual visits may be much too long for early detection. Therefore, the patients must be integrated into early detection strategies. It is very important that they are aware of all the symptoms that may possibly indicate neuropathy (Table 7.2). Any such symptom should prompt a visit to the doctor’s office or a diabetes center.

Table 7.2 Symptoms of diabetic neuropathies

On extremities or trunk: Deafness, numbness, tiredness Tingling, clumsy fingers Cold, numb, burning feet Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|