I. Vascular complications

SMV or portal vein thrombosis

Bowel ischemia

Hepatic ischemia

Omental infarction

II. Nonvascular complications

Anastomosis site leakage (except Pancreaticoenteric anastomosis)

Anastomosis site ulcer

Perioperative catheter related—PEG or feeding tube

A-loop syndrome

Ascites and chyle ascites

Bilio-enteric anastomosis strictures

Cholangitis and hepatic abscesses

Cholelithiasis

33.2 Portal Venous System Thrombosis

Portal venous system thrombosis (PVST) is a rare but potentially lethal complication after pancreatic resections. Since the symptoms range from asymptomatic patients to rapid progression with bowel necrosis, prompt diagnosis and appropriate treatment are essential. However, because of low incidence, there is no opportunity to experience; period of treatment can be missed and led to death.

Depending on operative procedure, rates were highest in total pancreatectomy with splenectomy, followed by pancreaticoduodenectomy and distal pancreatectomy. Vascular injury or portal vein reconstruction during surgery increases the risk of postoperative thrombosis formation.

The pathogenesis of PVST after pancreatic surgery is probably multifactorial. (1) Surgery increases the risk of thrombosis by causing endothelial damage or by decreasing blood flow in the portal vein and its branches. For example, splenectomy has been shown to lead to a high incidence of portal system thrombosis [1, 2]. However, this was not observed in the present study. (2) Malignancy induces a hypercoagulable state, and tumor recurrence after pancreatic surgery is not uncommon. (3) Inflammatory conditions before surgery (e.g., chronic pancreatitis) and after surgery (e.g., abscesses/pancreatitis) may promote thrombus formation.

Symptoms can range from abdominal pain, fever, fatigue, nausea and vomiting, and abdominal distention to shortness of breath. If PVST occurs, ascites, liver abscess, and sepsis and pulmonary embolism can be observed as complications.

Computed tomography and ultrasonography (US) are important in the detection of PVST. Contrast enhanced computed tomograpy (CECT) was used for diagnosing PVST in most patients and has a sensitivity of 90% and high diagnostic specificity (99%) [3]. Color Doppler imaging can be also used, and it has higher sensitivity (93%) and equal specificity (99%) [3]. The surgeon, therefore, can utilize a multimodality approach as it relates to the workup of this potentially lethal complication.

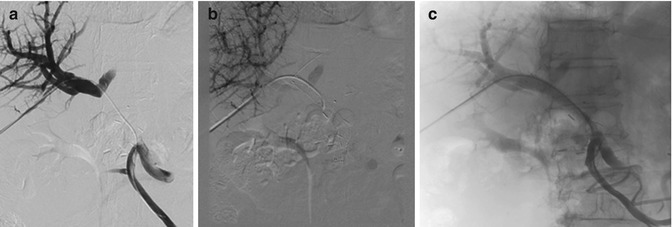

One of questions behind one study was if—and then how—thrombosis after surgery in the portal vein system should be treated [4]. Generally, when PVST was diagnosed, therapy was usually initiated with therapeutic doses of LMWH (dalteparin sodium 200 U/kg body weight/day) if the patients had no severe obstructive signs of the portal vein system, such as bowel wall edema. For severe occlusion, thrombectomy might be performed immediately as a second surgery. The importance of expeditious treatment with systemic anticoagulation is widely recognized for venous thrombosis in general, and recanalization of acute portal venous system thrombosis may occur in most patients following treatment (Fig. 33.1). However, the treatment was not universally effective in all patients.

Fig. 33.1

Recanalization of acute portal venous system thrombosis may occur by portal vein stenting. (a) Development of portal vein thrombosis after operation. (b) Portal vein stenting. (c) Recanalization of portal vein flow after stenting

33.3 Marginal Ulcer

Marginal ulcer (MU) is a well-known and morbid complication of pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD), pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy (PPPD), and total pancreatectomy (TP). In the past, since the incidence of marginal ulcer was insignificant among patients who underwent pancreaticoduodenectomy with vagotomy, while the incidence was nearly 50% among patients without vagotomy, vagotomy was strongly recommended [5].

In the noughties, it was reported that in patients after pancreaticoduodenectomy or total pancreatectomy without vagotomy, marginal ulcer occurred in 11.7% [6]. Recently with the development of antisecretory medication, there have been many changes in ulcer treatment. Thus during PD or PPPD, vagotomy is usually not performed. However, there is no accurate report about recent incidence of marginal ulcer nor prescription of antisecretory medication.

The recent report of Zyromski et al. showed a mean incidence of ulceration after PD or PPPD of 2.5% (confidence interval (CI) 1.8–3.2%) with a median time to diagnosis of 15.5 months [7]. Pylorus preservation was associated with an MU rate of 2.0% (CI 1.0–2.9%), while classic PD procedures report an overall rate of 2.6% (CI 1.6–3.6%). Documented use of postoperative antisecretory medication was associated with a reduced rate of 1.4% (CI 0.1–1.7). Etiologic factors affecting the occurrence of MU are related to altered gastrointestinal anatomy: duodenal resection removes the thick, alkaline-rich mucus buffer provided by Brunner’s glands, and unbuffered gastric content can be ulcerogenic to the bowel wall.

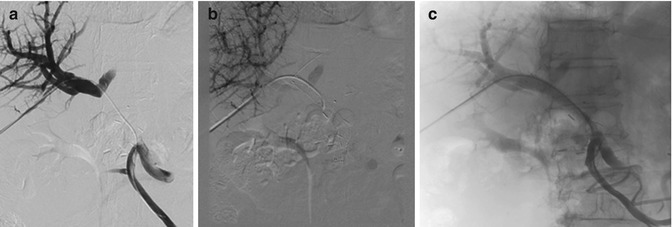

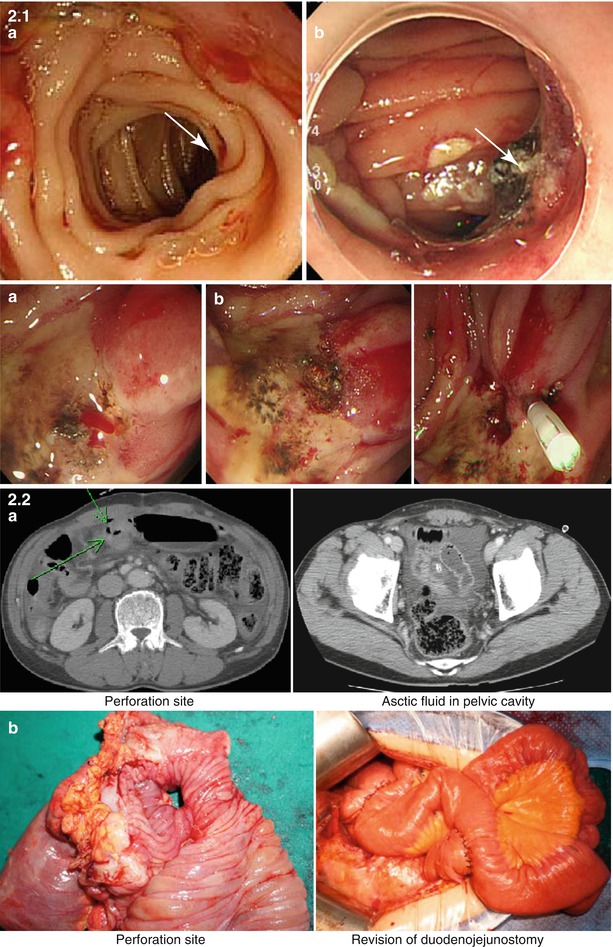

Most of practiced pancreatic surgeons have the experience of severe epigastric pain, panperitonitis due to perforation, or bleeding (dizziness, melena, hematemesis) due to marginal ulcer after PD or PPPD (Fig. 33.2). In these cases, ulcer medication, vigorous endoscopic treatment, or surgical treatment will be conducted. In cases where severe bleeding or panperitonitis due to free perforation occurs, mortality rate over 20% is reported; if there is high risk of marginal ulcer before surgery, if the patient has peptic ulcer disease history, or if the patient has favorable prognosis and potential for long-term survival, bilateral truncal vagotomy can be considered.

Fig. 33.2

Recurrent bleeding or free perforation from marginal ulcer developed after PD or PPPD. 2-1 Recurrent bleeding from marginal ulceration and it was controlled by coagulation or clipping. (a) Bleeding from marginal ulceration. (b) Bleeding control by endoscopic therapy (ulceration). 2-2 Free perforation from marginal ulceration and its treatment. 2-2 (a) Preoperative CT finding of marginal ulcer perforation. 2-2 (b) Operation finding

33.4 Chyle Ascites

Chyle leak complicating pancreatic resection is reported to occur in 1.3–10.8% of cases [8–10]. Postoperative intra-abdominal chyle leak is most likely secondary to surgical disruption of the cisterna chyli or one of its major lymphatic tributaries [11]. Predisposing factors of chyle leak include more radical lymphadenectomy [8], concomitant vascular resection [8], and early institution of enteral nutrition [9]. Chyle leak imposes the additional morbidity of large fluid volume losses together with protein, electrolyte, immunoglobulin, and lymphocyte depletion on already debilitated patients [8]. Recently many experienced surgeons insist that enteral nutrition should be used whenever possible even in patients undergoing pancreatic surgery [12]. I experienced draining fluid milky color change sometimes after starting enteral tube feeding. So early EN correlated with an increase in chylous drainage [9].

The diagnosis of CL was made clinically after observation of a milky appearance of drain fluid at volumes greater than 200 ml/day (Fig.33.3). In cases which CL was suspected but clinical features were equivocal, CL was diagnosed in the presence of drain fluid triglyceride concentration twice that of serum or >110 mg/dL [13]. In addition, the definition of chyle leak shows some differences depending on the researcher. The incidence differs depending on surgical extent, but there are also differences depending on how chyle leak is defined, so that efforts should be make on finding a consensus between researchers. No patient required lymphangiography or any other radiological test for confirmation of diagnosis.

Fig. 33.3

The diagnosis of chyle leak was made clinically after observation of a milky appearance of drain

Treatment can include dietary modification, enteral nutrition (EN) with fat content modification, bowel rest with parenteral nutrition (PN), octreotide administration, and surgery.

According to the severity of CL, we can choose one of above treatments. Most of chyle leaks after pancreas surgery are successfully controlled by bowel rest with parenteral nutrition or conservative measures, including conversion to an MCT enteral feeding regimen and careful fluid balance monitoring with supplemental intravenous rehydration up to 80%. Miyazaki group [13] recommended treatment of algorithm of postoperative chylous ascites, and it seems to be reasonable (Fig. 33.4). Once oral intake was established, patients with CL were maintained on an oral MCT diet until drain output ceased.