Neuroendocrine cancer commonly metastasizes to the liver and often presents as unresectable disease. Liver resection or debulking most of the tumor provides a survival advantage for patients. Whether used alone or in combination with resection, radiofrequency ablation provides a unique tool to destroy metastases to the liver and spare hepatic parenchyma. Although randomized trials are lacking, retrospective series provide promising data to consider radiofrequency ablation in the management of hepatic neuroendocrine metastases.

Metastasis of neuroendocrine tumors varies according to the primary diagnosis and is reported to occur as frequently in 75% of glucagonomas to as rare as 5% to 10% of carcinoid tumors. Tumors generally advance in an indolent predictable pattern that allows multiple therapeutic options. Although the reported incidence of neuroendocrine tumors in the United States is only 1 to 2 per 100,000 people, more than half the patients with clinically apparent tumor have or will develop liver metastases. Surgery remains the primary therapy through either cytoreductive debulking or curative resection. The introduction of radiofrequency ablation (RFA) has allowed physicians to surgically address a larger population of patients with a curative intent ablation alone, or in combination with resection. Reports to date regarding RFA management are largely single-institution retrospective series. This article provides a brief summary of the types of neuroendocrine tumors and therapies, with focus on RFA of neuroendocrine hepatic metastases.

Gastrointestinal neuroendocrine neoplasms

The gastrointestinal tract is the most common site for carcinoid tumors to occur, with the most common specific sites being the appendix, small intestine, and rectum. Appendiceal tumors are typically small with most less than 1 cm and are primarily managed by routine appendectomy. Rectal carcinoids are also typically less aggressive and often managed by local excision alone.

The most common and clinically threatening site of origin for carcinoid is the small intestine. These tumors are the most frequent to involve the liver at presentation, and liver metastasis eventually develop in up to 85% of cases.

In advanced cases, carcinoid syndrome may occur characterized by flushing, diarrhea, asthma, bronchospasm, or in very advanced cases, carcinoid heart disease. This unique symptomatic expression typically occurs in 35% to 50% of patients with hepatic disease. Most patients have increased serotonin production and the levels of urinary 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid are directly related to the severity of symptoms. Typically these cancers are very slow growing and duration of disease from diagnosis to eventual death is more than 9 years. The tumor has accurately been described as “cancer in slow motion.” In those with unresectable disease, 5-year median survival is reported to approach 30%.

Islet cell neoplasms

Pancreatic islet cell tumors are functional in about 50% of cases and typically produce more than 1 hormone. Neoplasms are named for the dominant hormone produced, such as insulinoma, gastrinoma, glucagonoma, VIPoma, and somatostatinoma. Considerable morbidity and mortality may occur as a result of the production of the dominant hormone. The severity of the syndrome is proportional to the overall tumor burden.

These tumors also frequently metastasize to the liver with incidence varying by type. Metastases most commonly occur in gastrinomas and least frequently in insulinomas. Despite the potential for severe symptoms, the clinical course of patients even in the presence of distant metastases, can be quite indolent with 5-year survival approaching 30%.

Treatment of neuroendocrine hepatic metastases

Surgical intervention is considered the first choice for management, however many patients present with a disease burden or hepatic parenchymal location that prevents curative surgery or cytoreductive surgery. Somatostatin analogues, hepatic artery embolization, and systemic chemotherapy are also used depending on the location of the primary, systemic symptoms, and feasibility of surgery.

Surgical resection

When technically possible, resection of the primary and the liver metastases affords the greatest survival advantage. Hepatic tumors are often well circumscribed rather than infiltrative and thus liver resection may be a feasible option with acceptable margins.

Patients with metastatic disease are assessed for resection with high-quality magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computed tomography (CT). Resection of the primary and 90% of the metastatic disease is the proposed goal for surgical intervention. This strategy of aggressive resection has produced 5-year survival rates of approximately 60%. One retrospective study even reported a median survival of 7 years, and because of slow growth of the tumor, 35% were alive at 10 years.

Most patients present with advanced bilobar disease and approximately 10% are considered for surgical resection alone. In addition to advanced bilobar disease, approximately 45% of patients possess concurrent extrahepatic disease. Surgical intervention is complex often involving concurrent primary tumor resection. Mortality ranges up to 6%, with complications occurring in 5% to 30% of cases.

Survival of those treated with cytoreductive intent is similar to those resected with curative intent. Survival is also comparable in metastatic carcinoid and islet cell tumors and hormonally active metastatic disease does not portend a worse outcome.

Surgical resection has been shown to provide superior 5-year survival in selected patients when compared with medical or hepatic artery embolization therapy. Blumgart and colleagues reported 76% 5-year survival in a surgical group compared with 53% in an embolization group, but no survivors with medical management alone. Symptom control may be gained with the surgical resection and is reported to improve in 96% to 100% of cases with a median time to symptom recurrence of 45 months. Long-term recurrence after resection is very high and some have predicted disease will recur in all patients by 7.5 years.

Liver transplantation is only considered in highly selected patients with a previously controlled primary tumor and no extrahepatic disease. However, even in carefully selected patients, recurrence is high. In a review of 103 patients, overall 5-year survival was 47% and recurrence-free survival was only 24%.

Hepatic artery embolization

In patients who are deemed unresectable, hepatic artery embolization may offer an effective palliative approach. Because these hypervascular tumors are primarily fed by the hepatic artery rather than the portal vein, the hepatic artery provides unique access to the tumor. This regional approach does not prevent subsequent surgery or concurrent systemic therapy and response rates of 50% to 96% have been reported. Duration of the response has been the greatest challenge to this treatment option with reports ranging from 4 to 18 months.

Medical therapy

Somatostatin analogues are the first-line systemic agent used in the management of functioning neuroendocrine tumors. These analogues bind to the somatostatin receptors that are present on most neuroendocrine tumor cells. These agents have been shown to effectively control symptoms and improve quality of life for most patients. Recent evidence from the randomized PROVID study shows that analogues have affected progression-free survival, but overall survival was not significantly changed. Cytotoxic agents are less effective primarily because neuroendocrine tumors are well-differentiated and have a low proliferative index.

Radiofrequency ablation

RFA is the primary modality used currently for ablation for neuroendocrine metastases to the liver. The introduction of RFA has allowed for intraoperative destruction of lesions and/or recurrences. Technologic advances such as the internally cooled ablation tips have made delivery more efficient and effective. Laparoscopic and percutaneous approaches have also minimized morbidity associated with treatment. Ultrasound guidance is the standard of care to identify lesions of interest and confirm proper ablation probe placement. Based on the surgical experience of debulking resulting in improved survival and symptoms, ablations that destroy more than 90% of the tumor burden are now considered. The greatest success in ablation is noted in smaller lesions and thus appropriate selection of cases for RFA is vital. Although other forms of ablation exist such as ethanol injection or more recently, microwave ablation, our discussion in this article is focused on RFA.

There are no prospective trials showing survival advantage for RFA management of neuroendocrine cancer, however several retrospective analyses have indicated a seemingly clear benefit of RFA for symptom relief and survival for various types of cancer.

Berber and colleagues have published large series of hepatic neuroendocrine tumors undergoing RFA. They have reported 234 ablations in 34 patients and achieved symptom relief in 95% of cases with a median duration of 10 months. Decreased levels of at least 1 hormone marker were noted in 65% of patients. New liver metastases developed in 28% at a mean follow-up of 1.6 years. Local recurrence at the ablation site was noted to occur in only 3% of treated metastasis sites.

The symptom response to RFA has been documented in other series as well and may allow patients to discontinue the use of octreotide therapy to control carcinoid symptoms. RFA has also been reported in patients unresponsive to hepatic artery embolization allowing octreotide to be decreased or discontinued.

Hellman and colleagues reported 21 patients undergoing 43 ablations with an intraoperative or percutaneous approach. Mean size of tumor was 2 cm and 15 patients were treated with curative intent. At 2-year follow-up, 95% were without evidence of disease. Although there is little chance of cure, the treatment of liver metastasis remains important both for control of symptoms and slow progression.

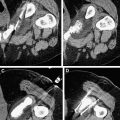

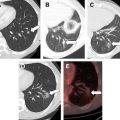

Hepatic resection remains the standard of care for patients, however RFA is an important therapeutic option ( Box 1 ). Superficial tumors are not ideal for RFA, as they can be enucleated easily with minimal loss of hepatic function. The number of lesions or their location are the primary reasons few patients are resection candidates. Complementary ablation extends the group of patients for operative management as it can be used alone, or combined with liver resection. RFA allows for more aggressive management of small foci of disease deep within the liver in turn voiding major resection. This approach minimizes the surrounding parenchymal loss protecting the necessary hepatic reserve ( Fig. 1 ).