Despite a profusion of studies over the past several years documenting racial differences in cancer outcomes, there is a paucity of data as to the root causes underlying these observations. This article reviews work to date focusing on black-white differences in cancer outcomes, explores potential mechanisms underlying these differences, and identifies patient, physician, and health care system factors that may account for persistent racial disparities in cancer care. Research strategies to elucidate the relative influence of these various factors and policy recommendations to reduce persistent disparities are also discussed.

- •

Racial differences in outcomes have been reported for almost all cancer types.

- •

The preponderance of the medical literature to date suggests that black-white differences in cancer outcomes are largely explained by failure to provide suitable cancer care rather than by racial differences in stage at presentation, tumor biology, or response to treatments.

- •

Studies using novel research methodologies and accounting for sociodemographic, physician, and hospital factors are needed to identify potentially modifiable patient, physician, and health care system factors that may underlie persistent racial disparities in receipt and quality of surgical and adjuvant therapy.

- •

Ongoing efforts to improve access to care, enhance diversity in the surgical workforce, navigate minority cancer patients through the health care system, and enhance adherence to cancer-specific best practices are warranted.

Racial differences in cancer outcomes: scope of the problem

Although racial differences in outcomes have been reported for almost all cancer types, this article focuses primarily on the 3 leading causes of cancer death in the United States for which the standard of care is well defined and surgical resection is the cornerstone of therapy: invasive breast cancer, non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), and colorectal cancer ( Table 1 ). Recent statistics indicate that age-adjusted breast cancer mortality rates are higher among black women than white women ( Table 2 ). Population-based studies suggest that although survival rates for women with breast cancer have improved over the past 2 decades, survival rates in black women have lagged behind, and the observed disparity is increasing. Black men have a significantly higher incidence rate and are almost 1.5 times as likely to die from lung cancer and bronchus cancer than are white men. Similarly, black men and black women have significantly higher cancer incidence rates and are approximately 1.5 more likely to die of colorectal cancer compared with their white counterparts.

| Men | Women | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Cases | % of Cases | Rank | No. of Cases | % of Cases | Rank | |

| Estimated New Cases | ||||||

| Breast | — | — | — | 230,480 | 30 | 1 |

| Lung and bronchus | 115,060 | 14 | 2 | 106,070 | 14 | 2 |

| Colon and rectum | 71,850 | 9 | 3 | 69,360 | 9 | 3 |

| Estimated Deaths | ||||||

| Breast | — | — | — | 71,340 | 26 | 2 |

| Lung and bronchus | 85,600 | 11 | 1 | 39,520 | 15 | 1 |

| Colon and rectum | 25,250 | 8 | 3 | 24,130 | 9 | 3 |

| Men | Women | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | Black | White | Black | |

| Incidence rates | ||||

| Breast | — | — | 121.9 | 114.6 |

| Lung and bronchus | 84.3 | 103.5 | 57.0 | 51.8 |

| Colon and rectum | 56.1 | 67.2 | 41.4 | 50.7 |

| Mortality rates | ||||

| Breast | — | — | 23.4 | 32.4 |

| Lung and bronchus | 68.3 | 87.5 | 41.6 | 39.6 |

| Colon and rectum | 20.6 | 30.5 | 14.4 | 21.0 |

Mechanisms underlying racial differences in cancer outcomes

Racial differences in cancer outcomes may be attributed to racial differences in stage at presentation, tumor biology, treatment efficacy, and/or failure to provide optimal cancer treatment.

Cancer Stage

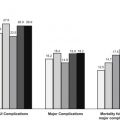

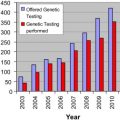

Data from the National Cancer Institute (NCI) Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) program have persistently shown than blacks with breast cancer, lung cancer, and colorectal cancer are more likely to present with advanced disease compared with whites ( Fig. 1 ). Failure to uncover black-white differences in biologic and tumor characteristics suggests that discrepancies in routine cancer screening between races may be involved. Studies further suggest that the effect of race on stage at presentation may be confounded by socioeconomic factors, including education, income, and insurance status. Irrespective of the mechanisms involved, black-white differences in cancer survival persist even when controlling for stage at presentation, suggesting that other factors likely account for observed racial differences in cancer outcomes ( Fig. 2 ).

Tumor Biology

Although racial differences in tumor biology (and natural history) may contribute to differences in cancer outcomes, their influence and true impact on outcomes remains controversial. In a study combining breast cancer incidence data from various SEER registries and mortality data from the National Center for Health Statistics, breast cancer mortality rates were similar for blacks and whites until the late 1970s, after which time the mortality rates among black women increased. This observation was associated with an increase in the calendar period mortality curves for blacks but not the birth cohort curves (which reflect differences in risk factors), suggesting that the greater mortality rate in blacks may have been attributable to differences in access to care or response to new treatments during this period. Studies also suggest that there are no apparent racial differences in the biologic aggressiveness, tumor characteristics, or efficacy of treatments for colorectal cancer. In the NCI Black/White Cancer Survival Study, the distribution of colon cancers by anatomic location, histology, and grade did not differ by race.

Treatment Toxicity and Efficacy

Treatment-related mortality

Several investigators have suggested that race is an independent predictor of poor outcomes after surgery. In a study using Medicare data, black race was associated with an increased risk of death after 7 of 8 major cardiovascular or cancer procedures (even when adjusting for comorbidity using administrative data codes). This effect, however, was attenuated or nonexistent when controlling for the proportion of black patients treated at the operating hospitals.

In a more recent study using data from the National Surgery Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP) Patient Safety in Surgery Study, blacks were more likely to present with greater comorbidity and more likely to undergo emergency surgery than whites. After controlling for all other patient/procedure-related factors, however, black race was associated with a higher risk of cardiac and renal postoperative occurrences but was not an independent predictor of overall morbidity or mortality.

With the exception of the NSQIP report, these studies have relied largely on administrative data sets, which are limited in the amount of clinical information available for accurate risk adjustment and can only be used to generate approximate measures of comorbidity, such as the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI). The apparent adverse effects of black race on postoperative outcomes in these studies may be due to failure to fully control for underlying comorbidity and/or structures and processes of care at the hospitals at which patients were treated rather than race per se (discussed later).

Efficacy of adjuvant therapy

Many studies suggest that there are no apparent racial differences in the efficacy or effectiveness of local and/or systemic therapy for breast cancer, lung cancer, or colorectal cancer. White women and black women with early-stage breast cancer treated with breast conservation therapy (BCT) have similar rates of local control. An analysis of several National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP) trials between 1982 and 1994 revealed no differences in disease-free survival between racial groups. Survival in whites and blacks with early-stage NSCLC is similar after resection. In patients with more advanced disease, race-related survival is also comparable after radiation and systemic therapy. Reanalyses of randomized, NSABP colorectal cancer adjuvant therapy trials revealed similar rates of nodal involvement and no black-white differences in disease-free survival.

Failure to Provide Optimal Cancer Treatment

There is a growing body of literature suggesting that black-white differences in cancer outcomes may be explained by failure to provide suitable cancer care in blacks, due to either underuse of therapy and/or receipt of suboptimal therapy.

Underuse of surgical resection

Surgical resection is the cornerstone of therapy in patients with nonmetastatic breast cancer, NSCLC, and colorectal cancer. Failure to perform resection in these patients represents a serious breach in the standard of care and poses a serious threat to patients’ quality of life and long-term survival.

Although the majority of studies to date in breast cancer patients have focused primarily on black-white differences in the use of BCT, a 2002 report that linked data from the Metropolitan Detroit SEER registry to Michigan Medicaid enrollment files reported underuse of surgical resection among blacks with breast cancer. In a multivariate analysis controlling for age, marital status, Medicaid enrollment, poverty status, and stage, black race was associated with an adjusted odds ratio (OR) of resection of 0.62 (95% CI, 0.42–0.90). In a recent study using a large, population-based sample of women with nonmetastatic breast cancer, black race was associated with underuse of curative resection (94.9% vs 96.4%, P <.001). Although black race had no apparent adverse effect on resection among rural patients, the adjusted OR for resection for urban black patients was 0.58 (95% CI, 0.41–0.82). These studies suggest that underuse of resection among urban black women with breast cancer is real and seems to extend across geographically diverse communities, independent of comorbidity or socioeconomic status (SES). Although the black-white differences in surgical resection rates in these studies are admittedly small, long-term, breast cancer survival is impossible without surgical resection. Therefore, even minor differences in surgical treatment can be considered clinically significant, particularly when surgery carries minimal risks to the patient.

Approximately one-third of patients with the most common type of lung cancer, NSCLC, present with early (stage I or II), potentially curable disease. If treated with resection, the 5-year survival rate of these patients approaches 40%. In contrast, the median survival of patients who are not resected or patients with locally advanced/metastatic disease is less than 1 year. Several studies have reported lower rates of lung resection among blacks with NSCLC, even when controlling for stage at presentation. Greenwald and colleagues reported that patients with stage I NSCLC in Detroit, San Francisco, and Seattle were less likely (by 12.7%) to undergo resection if they were black or of lower SES. In a seminal study using SEER-Medicare data from 1985 to 1993, the rate of surgery in black patients with stage I-II NSCLC was only 64.0% compared with 76.7% among whites ( P <.001). Black race was associated with a relative risk of resection of 0.54, even when controlling for the effects of age, gender, comorbidity, median income, and tumor stage. Overall, 5-year survival rates were lower for blacks compared with whites (26.4% vs 34.1%, P <.001). In contrast, the 5-year survival rates of black patients and white patients who underwent surgery were approximately similar (39.1 vs 42.9%, P = .10) as were survival rates among patients who did not undergo surgery (4% vs 5%, P = .25). The investigators concluded that the racial disparity in resection rates largely accounted for the lower survival rate among blacks in their study. In a more recent study of all cases of nonmetastatic NSCLC reported to the South Carolina Central Cancer Registry between 1996 and 2002, overall use of surgical resection (across races) was lower than previously reported, and blacks were significantly less likely to undergo surgery compared with whites (44.7% vs 63.4%, P <.001). After controlling for sociodemographics, comorbidity, and tumor factors, the adjusted OR for resection for blacks was 0.43 (95% CI, 0.34–0.55).

Several recent studies using state cancer registry data, SEER data, and the National Cancer Data Base (NCDB) have also reported lower rates of definitive resection among blacks with resectable colon and rectal cancers. A study of more than 80,000 Medicare beneficiaries with colorectal cancer reported that only 68% of blacks underwent surgical resection compared with 78% of whites. A study using SEER data reported rates of surgery of 94% among black patients with stage II-III rectal cancer compared with 96% among white patients. In a more recent study, underuse of surgery was greater among blacks with rectal cancer (82.0% vs 89.3% in whites, P <.001) compared with blacks with colon cancer (92.9% vs 94.5% in whites, P <.001). In a nationwide, hospital-based sample of 35,695 patients with rectal cancer treated between 2003 and 2005 culled from the NCDB, only 85.1% percent of blacks underwent definitive resection compared with 90.7% of whites. Black race was independently associated with underuse of surgery on multivariate analysis (OR 0.62; 95% CI, 0.54–0.71) even when controlling for comorbidity and SES/insurance status.

Underuse of adjuvant therapy

In addition to underuse of surgical resection, underuse of adjuvant radiation and/or systemic therapy in blacks with nonmetastatic breast cancer, NSCLC, and colorectal cancer may partly explain observed differences in survival. Despite similar rates of comorbidity, insurance coverage, and oncologic consultation, women with early-stage breast cancer from minority groups were half as likely to receive adjuvant therapy than were whites. Several population-based studies using SEER data have also reported lower rates of adjuvant radiation therapy after BCT.

A study that used SEER data reported that black race was associated with underuse of adjuvant radiotherapy, contradicting a previous analysis that used SEER-Medicare data. In a more recent study from the NCDB, however, there was no association between race and receipt or type of adjuvant therapy. A study of 3 population-based databases in California similarly found no association between race/ethnicity and use of adjuvant therapy when controlling for comorbidity, education, and poverty status. Taken as a whole, these studies suggest that whatever race-related barriers to surgical care may exist among black patients with rectal cancer, they do not seem to affect the quality of their nonsurgical cancer care.

Factors underlying underuse of cancer treatment

Patient factors

Misconceptions about cancer and its treatment

Patients’ misconceptions about cancer and its treatment may adversely impact their willingness to undergo surgery. In a national telephone survey, the misconception, “Treating cancer with surgery can cause it to spread throughout the body,” was endorsed by 41% of respondents. A significant proportion of respondents endorsed other misconceptions, including “The medical industry is withholding a cure for cancer from the public to increase profits” (27%); “All you need to beat cancer is a positive attitude, not treatment” (11%); and “Cancer is something that cannot be effectively treated” (13%). Respondents who were older, nonwhite, Southern, or indicated being less informed about cancer endorsed the most misconceptions.

In a related study of patients being treated at pulmonary and lung cancer clinics in Philadelphia, Los Angeles, and Charleston, 38% of patients stated that they believed that air exposure at surgery caused tumor spread and that black race was the most significant predictor of this belief; 19% of black patients stated that this belief was a reason for avoiding surgery, and 14% stated that they would not accept their physicians’ reassurance that the belief was false. In a recent prospective cohort study of patients with early-stage lung cancer from North Carolina and South Carolina, 45% of patients agreed with this belief and endorsement of this belief was significantly associated with subsequent failure to undergo surgery.

Patient preferences

Patients’ beliefs and preferences may affect their decision to undergo cancer treatment. Patients facing a tradeoff between quantity and quality of life may (paradoxically) opt to forgo potentially curative surgery. In one study, 20% of subjects facing T3 laryngeal cancer opted for radiation therapy (and a lower probability of survival, 30%–40%) over laryngectomy (and a higher probability of survival, 60%) to preserve their speech.

In a prospective study of black veterans and white veterans with carotid stenosis faced with the prospect of carotid angiography and carotid endarterectomy, blacks expressed higher aversion to surgery than whites. During follow-up, 20% of whites and 14% of blacks underwent endarterectomy, and highest aversion quartile was associated with a lower likelihood of undergoing surgery, even when accounting for clinical appropriateness. In a secondary analysis, increased age, black race, no previous surgery, lower level of chance locus of control, less trust of physicians, and less social support were associated with greater likelihood of surgery risk aversion.

In a 2004 study, blacks with colorectal cancer were more likely to refuse surgery when reasons for nonreceipt of surgery were analyzed using the SEER database. Concerns or fears about receiving a permanent stoma may affect patients’ willingness to pursue surgical consultation and/or follow-up with recommended surgery (which may explain why blacks with nonmetastatic rectal cancer were more likely to forgo radical resection and opt for local excision in a recent study from the NCDB). In a prospective cohort study of patients with early-stage lung cancer, the feeling that quality of life would be worse 1 year after lung cancer surgery was significantly higher among blacks than whites (42% vs 34%) and was associated with subsequent failure to undergo surgical resection.

Health care system factors

Access to care

Black-white differences in cancer care and outcomes may be partly explained by differences in access to care. In the Community Tracking Study Physician Survey, black Medicare beneficiaries were more likely to be cared for by physicians who were less well trained clinically and had more limited access to important clinical resources (eg, specialists, high-quality imaging, high-quality ancillary services, and nonemergency hospital admissions) than physicians who treated white patients. Lack of a regular source of health care was recently shown to be associated with underuse of surgical resection in patients with early-stage lung cancer, particularly among blacks.

Although underuse of surgery could also be related to lower referral rates for surgical consultation among blacks, the widely varying black-white differences in resection rates in patients with breast cancer, lung cancer, and colorectal cancer argue against systematic under-referral of blacks. In addition, a recent study showed that black race was a powerful, negative predictor of surgical resection even when the analysis was limited to patients who had received surgical consultation and been previously staged with mediastinoscopy.

To what extent does equal access to appropriate cancer care reduce black-white differences in treatment and outcomes? Dominitz and colleagues analyzed the effect of black race on surgery and adjuvant therapy in a cohort of 3176 colorectal cancer patients treated within the Veterans Administration (VA) equal access health care system. Irrespective of SES, blacks and whites had similar rates of surgery, radiation therapy, and chemotherapy (likely because referral patterns and payments were not barriers to care) and survival was similar across races. Equal health care coverage (ie, insurance), however, may not be sufficient to ensure equal access to care. Rogers and colleagues analyzed the effect of race on colorectal cancer outcomes in a population of elderly Tennesseans who were dually enrolled in both Medicaid and Medicare. Although there was no racial difference in overall mortality in a multivariate analysis controlling for comorbidity, stage, and treatment, only 86% of blacks received surgical therapy compared with 91% of whites ( P = .02).

Physician-patient communication

In a recent report from the cancer registry at the Henry Ford Health System in Detroit, black race had no apparent effect on the odds of being offered surgery for early-stage NSCLC (after controlling for comorbidity, pulmonary function, and tumor stage) but did have a negative effect on the rate at which surgery was declined by patients (OR 4.1; 95% CI, 0.34–0.55). In another study, black patients evaluated by a surgeon were more likely to have a negative recommendation for surgery (71.4% vs 67.0%, P <.05) and more likely to refuse surgery compared with whites (3.4% vs 2.0%, P = .013), suggesting that that miscommunication or bias during the patient-physician encounter was likely involved.

Several factors can influence patients’ decisions to undergo treatment. In a study of patients with advanced lung cancer, their caregivers, and medical oncologists, all 3 groups ranked the oncologist’s recommendation as the most important factor in decision making. Patients and caregivers ranked faith in God second (above the ability of treatment to cure their cancer), whereas physicians ranked faith last. Patients who ranked faith first were less educated and may not have fully understood the technical aspects or risks/benefits of their cancer treatments. Failure by physicians to acknowledge their patients’ strongly held beliefs might lead to unsatisfactory physician-patient interactions and suboptimal decision making. In a recent study of patients with early-stage lung cancer, patients who agreed with the statements, “faith alone cures disease” and “prayer will cure cancer,” were less likely to receive subsequent surgical resection. In addition, negative perceptions of physician-patient communication were associated with underuse of surgery across races.

In a recent analysis of audiotaped office visits between orthopedic surgeons and white versus black elderly patients, there were no significant differences in the content of various informed decision-making elements by race. When the encounters were evaluated for 4 relationship-building components of communication, however, coder ratings were significantly lower for responsiveness, respectfulness, and listening in visits with black patients. Not surprisingly, black patients were significantly less satisfied with the encounters and their surgeons, even after controlling for potential confounders.

Physician beliefs and biases

Persistent erroneous beliefs (reinforced by published reports) about the adverse effect of black race on surgical mortality and/or treatment efficacy may deter physicians from referring black patients with potentially curable cancers for surgical resection and/or adjuvant therapy. Race and SES can also affect physicians’ perceptions of patients and subsequent treatment recommendations. In a study of physicians from 8 New York hospitals, black patients of low SES were perceived more negatively by physicians during a postangiogram encounter. More specifically, blacks were more likely to be rated as less intelligent and educated, less likely to have poor social support, and more likely to be at risk for noncompliance.

Perceived racism by patients can also undermine the physician-patient relationship and ultimately result in mistrust and refusal to proceed with recommended treatments. In a survey of Medicare beneficiaries with localized breast cancer, blacks reported perceiving more ageism and racism in the health care system compared with whites, and ageism was associated with higher rates of mastectomy (compared with BCT) and omission of radiation after BCT. In a study of patients from North Carolina and South Carolina, 62% of patients with early-stage lung cancer (73% of blacks and 50% of whites) agreed or mildly disagreed that patients receive worse care due to their race, and endorsement of this belief was associated with failure to undergo surgical resection for lung cancer. Furthermore, increasing distrust in the health care system was associated with an almost 2-fold increase in failure to undergo surgery.

Factors underlying receipt of suboptimal cancer treatment

Physician knowledge and expertise

Black patients with nonmetastatic cancer may be more likely to be referred to less experienced surgeons with worse perioperative outcomes. In a study from South Carolina, approximately 50% and 60% of lobectomies and pneumonectomies, respectively, for lung cancer were performed by general surgeons, and the perioperative mortality after lobectomy was significantly higher among patients treated by general surgeons (5.3% vs 3.0%, P <.05). In a study analyzing the effect of surgeon volume versus hospital volume on outcomes after rectal cancer resection, surgeon volume was not associated with either 30-day mortality of rate of sphincter preservation. Surgeon volume was strongly associated with 2-year mortality, however, and was a stronger predictor of long-term survival than hospital volume.

It is possible that black patients are more likely to be referred to less experienced surgeons, who in turn, may be more likely to recommend more radical (and perhaps less palatable) surgery. Some studies have reported lower rates of BCT and sphincter preservation in blacks with breast cancer and rectal cancer, respectively. More recent work, however, has reported underuse of surgery but similar rates of sphincter preservation and adjuvant therapy among resected patients (suggesting that whatever barriers to care existed preoperatively, they did not seem to affect patients’ intraoperative or postoperative care).

Hospital factors

In a recent report from California, blacks were significantly more likely to undergo surgery at low-volume centers for 6 of 10 operations (including lung cancer resection and pancreatectomy), even when controlling for comorbidity, insurance status, rural residence, and proximity to low-volume, medium-volume, and high-volume hospitals. In addition, Medicaid patients (and uninsured patients) were also more likely to receive care at low-volume hospitals compared with Medicare patients. A recent analysis from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample also revealed that blacks who underwent lung resection were less likely to undergo surgery at high-volume hospitals and more likely to die postoperatively. These and other studies risk-adjusted outcomes using administrative data and may have underestimated the true extent of comorbidity among precisely those patients who would have been more likely to receive care at low-volume centers (ie, minority and underfunded patients). In contrast, a report from the VA-NSQIP detected no statistically significant association between procedure or specialty volume and 30-day mortality rate when outcomes were risk-adjusted using the more rigorous NSQIP methodology. “Evidence-based” hospital referral of selected patients to high-volume centers may not be practical, could exacerbate current racial disparities in access to care, and may inadvertently erode the level of surgical care at “low-volume” hospitals in rural and underserved areas. Recent work suggests that surgeon volume is a better predictor of rectal cancer outcomes than hospital volume and that the effect of hospital surgical volume may be negligible in patients who receive standard adjuvant therapy.

Hospital racial composition has also been shown to be associated with long-term outcomes in patients with breast cancer or colon cancer and attenuate the effect of individual patients’ race within hospitals. In a report of California Cancer Registry data, hospitals with a high Medicaid use rate (which cared for a disproportionate share of minority patients) had significantly higher 30-day and 1-year mortality rates compared with other hospitals. Taken together, these studies suggest that financial and/or resource constraints at the hospitals at which minorities are cared for may result in suboptimal care and disparities in treatment and outcomes. In a study of Medicare beneficiaries with cancer, black race was associated with worse 1-year and 3-year survival rates (largely due to later stage of disease at presentation and underuse of cancer-directed surgery); black race had no apparent adverse effect on outcomes, however, when the analysis was restricted to patients treated at NCI-designated cancer centers.

Moderators of receipt and quality of cancer treatment

Socioeconomic status

To some extent, race is a sociocultural construct and its apparent effect on health care access, use, and outcomes can be mediated and moderated by SES. In the NCI Black/White Cancer Survival Study, 26% of blacks lived at or below 125% of the poverty level income compared with only 9% of whites. Increasing income was associated with decreasing all-cause mortality, and controlling for poverty status eradicated the apparent, increased risk of cancer death among black patients with stage II-III colon cancer. In a recent study, black race was a powerful predictor of underuse of surgical resection in patients with rectal cancer, but its adverse was limited to patients living in poverty. Similarly, underuse of radiation after BCT was higher among blacks living greater distances from a cancer center or in areas of high poverty, whereas this effect was not seen in whites. Despite similar health care coverage, patients living in poverty may have worse access to financial and/or social resources needed to successfully negotiate the costs and inherent complexities of multidisciplinary cancer care.

Urban/rural status

Several studies have reported an association between rural residence and underuse of BCT (and adjuvant radiation after BCT) among women with invasive breast cancer. In a recent study, rural residence was associated with underuse of surgery across races, and black race had no apparent adverse effect on resection rates among rural patients. Rural women are less likely to have had a recent mammogram or breast examination compared with urban women (even when they report similar access to patient care) and tend to have more negative attitudes about breast cancer (despite having a similar knowledge base about the disease). Rural residents also experience limited access to health care (due to longer travel distances), fewer benefits (such as paid sick leave), fewer support services (such as childcare), and scant access to specialty physicians, including surgeons.

Mechanisms underlying racial differences in cancer outcomes

Racial differences in cancer outcomes may be attributed to racial differences in stage at presentation, tumor biology, treatment efficacy, and/or failure to provide optimal cancer treatment.

Cancer Stage

Data from the National Cancer Institute (NCI) Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) program have persistently shown than blacks with breast cancer, lung cancer, and colorectal cancer are more likely to present with advanced disease compared with whites ( Fig. 1 ). Failure to uncover black-white differences in biologic and tumor characteristics suggests that discrepancies in routine cancer screening between races may be involved. Studies further suggest that the effect of race on stage at presentation may be confounded by socioeconomic factors, including education, income, and insurance status. Irrespective of the mechanisms involved, black-white differences in cancer survival persist even when controlling for stage at presentation, suggesting that other factors likely account for observed racial differences in cancer outcomes ( Fig. 2 ).

Tumor Biology

Although racial differences in tumor biology (and natural history) may contribute to differences in cancer outcomes, their influence and true impact on outcomes remains controversial. In a study combining breast cancer incidence data from various SEER registries and mortality data from the National Center for Health Statistics, breast cancer mortality rates were similar for blacks and whites until the late 1970s, after which time the mortality rates among black women increased. This observation was associated with an increase in the calendar period mortality curves for blacks but not the birth cohort curves (which reflect differences in risk factors), suggesting that the greater mortality rate in blacks may have been attributable to differences in access to care or response to new treatments during this period. Studies also suggest that there are no apparent racial differences in the biologic aggressiveness, tumor characteristics, or efficacy of treatments for colorectal cancer. In the NCI Black/White Cancer Survival Study, the distribution of colon cancers by anatomic location, histology, and grade did not differ by race.

Treatment Toxicity and Efficacy

Treatment-related mortality

Several investigators have suggested that race is an independent predictor of poor outcomes after surgery. In a study using Medicare data, black race was associated with an increased risk of death after 7 of 8 major cardiovascular or cancer procedures (even when adjusting for comorbidity using administrative data codes). This effect, however, was attenuated or nonexistent when controlling for the proportion of black patients treated at the operating hospitals.

In a more recent study using data from the National Surgery Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP) Patient Safety in Surgery Study, blacks were more likely to present with greater comorbidity and more likely to undergo emergency surgery than whites. After controlling for all other patient/procedure-related factors, however, black race was associated with a higher risk of cardiac and renal postoperative occurrences but was not an independent predictor of overall morbidity or mortality.

With the exception of the NSQIP report, these studies have relied largely on administrative data sets, which are limited in the amount of clinical information available for accurate risk adjustment and can only be used to generate approximate measures of comorbidity, such as the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI). The apparent adverse effects of black race on postoperative outcomes in these studies may be due to failure to fully control for underlying comorbidity and/or structures and processes of care at the hospitals at which patients were treated rather than race per se (discussed later).

Efficacy of adjuvant therapy

Many studies suggest that there are no apparent racial differences in the efficacy or effectiveness of local and/or systemic therapy for breast cancer, lung cancer, or colorectal cancer. White women and black women with early-stage breast cancer treated with breast conservation therapy (BCT) have similar rates of local control. An analysis of several National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP) trials between 1982 and 1994 revealed no differences in disease-free survival between racial groups. Survival in whites and blacks with early-stage NSCLC is similar after resection. In patients with more advanced disease, race-related survival is also comparable after radiation and systemic therapy. Reanalyses of randomized, NSABP colorectal cancer adjuvant therapy trials revealed similar rates of nodal involvement and no black-white differences in disease-free survival.

Failure to Provide Optimal Cancer Treatment

There is a growing body of literature suggesting that black-white differences in cancer outcomes may be explained by failure to provide suitable cancer care in blacks, due to either underuse of therapy and/or receipt of suboptimal therapy.

Underuse of surgical resection

Surgical resection is the cornerstone of therapy in patients with nonmetastatic breast cancer, NSCLC, and colorectal cancer. Failure to perform resection in these patients represents a serious breach in the standard of care and poses a serious threat to patients’ quality of life and long-term survival.

Although the majority of studies to date in breast cancer patients have focused primarily on black-white differences in the use of BCT, a 2002 report that linked data from the Metropolitan Detroit SEER registry to Michigan Medicaid enrollment files reported underuse of surgical resection among blacks with breast cancer. In a multivariate analysis controlling for age, marital status, Medicaid enrollment, poverty status, and stage, black race was associated with an adjusted odds ratio (OR) of resection of 0.62 (95% CI, 0.42–0.90). In a recent study using a large, population-based sample of women with nonmetastatic breast cancer, black race was associated with underuse of curative resection (94.9% vs 96.4%, P <.001). Although black race had no apparent adverse effect on resection among rural patients, the adjusted OR for resection for urban black patients was 0.58 (95% CI, 0.41–0.82). These studies suggest that underuse of resection among urban black women with breast cancer is real and seems to extend across geographically diverse communities, independent of comorbidity or socioeconomic status (SES). Although the black-white differences in surgical resection rates in these studies are admittedly small, long-term, breast cancer survival is impossible without surgical resection. Therefore, even minor differences in surgical treatment can be considered clinically significant, particularly when surgery carries minimal risks to the patient.

Approximately one-third of patients with the most common type of lung cancer, NSCLC, present with early (stage I or II), potentially curable disease. If treated with resection, the 5-year survival rate of these patients approaches 40%. In contrast, the median survival of patients who are not resected or patients with locally advanced/metastatic disease is less than 1 year. Several studies have reported lower rates of lung resection among blacks with NSCLC, even when controlling for stage at presentation. Greenwald and colleagues reported that patients with stage I NSCLC in Detroit, San Francisco, and Seattle were less likely (by 12.7%) to undergo resection if they were black or of lower SES. In a seminal study using SEER-Medicare data from 1985 to 1993, the rate of surgery in black patients with stage I-II NSCLC was only 64.0% compared with 76.7% among whites ( P <.001). Black race was associated with a relative risk of resection of 0.54, even when controlling for the effects of age, gender, comorbidity, median income, and tumor stage. Overall, 5-year survival rates were lower for blacks compared with whites (26.4% vs 34.1%, P <.001). In contrast, the 5-year survival rates of black patients and white patients who underwent surgery were approximately similar (39.1 vs 42.9%, P = .10) as were survival rates among patients who did not undergo surgery (4% vs 5%, P = .25). The investigators concluded that the racial disparity in resection rates largely accounted for the lower survival rate among blacks in their study. In a more recent study of all cases of nonmetastatic NSCLC reported to the South Carolina Central Cancer Registry between 1996 and 2002, overall use of surgical resection (across races) was lower than previously reported, and blacks were significantly less likely to undergo surgery compared with whites (44.7% vs 63.4%, P <.001). After controlling for sociodemographics, comorbidity, and tumor factors, the adjusted OR for resection for blacks was 0.43 (95% CI, 0.34–0.55).

Several recent studies using state cancer registry data, SEER data, and the National Cancer Data Base (NCDB) have also reported lower rates of definitive resection among blacks with resectable colon and rectal cancers. A study of more than 80,000 Medicare beneficiaries with colorectal cancer reported that only 68% of blacks underwent surgical resection compared with 78% of whites. A study using SEER data reported rates of surgery of 94% among black patients with stage II-III rectal cancer compared with 96% among white patients. In a more recent study, underuse of surgery was greater among blacks with rectal cancer (82.0% vs 89.3% in whites, P <.001) compared with blacks with colon cancer (92.9% vs 94.5% in whites, P <.001). In a nationwide, hospital-based sample of 35,695 patients with rectal cancer treated between 2003 and 2005 culled from the NCDB, only 85.1% percent of blacks underwent definitive resection compared with 90.7% of whites. Black race was independently associated with underuse of surgery on multivariate analysis (OR 0.62; 95% CI, 0.54–0.71) even when controlling for comorbidity and SES/insurance status.

Underuse of adjuvant therapy

In addition to underuse of surgical resection, underuse of adjuvant radiation and/or systemic therapy in blacks with nonmetastatic breast cancer, NSCLC, and colorectal cancer may partly explain observed differences in survival. Despite similar rates of comorbidity, insurance coverage, and oncologic consultation, women with early-stage breast cancer from minority groups were half as likely to receive adjuvant therapy than were whites. Several population-based studies using SEER data have also reported lower rates of adjuvant radiation therapy after BCT.

A study that used SEER data reported that black race was associated with underuse of adjuvant radiotherapy, contradicting a previous analysis that used SEER-Medicare data. In a more recent study from the NCDB, however, there was no association between race and receipt or type of adjuvant therapy. A study of 3 population-based databases in California similarly found no association between race/ethnicity and use of adjuvant therapy when controlling for comorbidity, education, and poverty status. Taken as a whole, these studies suggest that whatever race-related barriers to surgical care may exist among black patients with rectal cancer, they do not seem to affect the quality of their nonsurgical cancer care.

Factors underlying underuse of cancer treatment

Patient factors

Misconceptions about cancer and its treatment

Patients’ misconceptions about cancer and its treatment may adversely impact their willingness to undergo surgery. In a national telephone survey, the misconception, “Treating cancer with surgery can cause it to spread throughout the body,” was endorsed by 41% of respondents. A significant proportion of respondents endorsed other misconceptions, including “The medical industry is withholding a cure for cancer from the public to increase profits” (27%); “All you need to beat cancer is a positive attitude, not treatment” (11%); and “Cancer is something that cannot be effectively treated” (13%). Respondents who were older, nonwhite, Southern, or indicated being less informed about cancer endorsed the most misconceptions.

In a related study of patients being treated at pulmonary and lung cancer clinics in Philadelphia, Los Angeles, and Charleston, 38% of patients stated that they believed that air exposure at surgery caused tumor spread and that black race was the most significant predictor of this belief; 19% of black patients stated that this belief was a reason for avoiding surgery, and 14% stated that they would not accept their physicians’ reassurance that the belief was false. In a recent prospective cohort study of patients with early-stage lung cancer from North Carolina and South Carolina, 45% of patients agreed with this belief and endorsement of this belief was significantly associated with subsequent failure to undergo surgery.

Patient preferences

Patients’ beliefs and preferences may affect their decision to undergo cancer treatment. Patients facing a tradeoff between quantity and quality of life may (paradoxically) opt to forgo potentially curative surgery. In one study, 20% of subjects facing T3 laryngeal cancer opted for radiation therapy (and a lower probability of survival, 30%–40%) over laryngectomy (and a higher probability of survival, 60%) to preserve their speech.

In a prospective study of black veterans and white veterans with carotid stenosis faced with the prospect of carotid angiography and carotid endarterectomy, blacks expressed higher aversion to surgery than whites. During follow-up, 20% of whites and 14% of blacks underwent endarterectomy, and highest aversion quartile was associated with a lower likelihood of undergoing surgery, even when accounting for clinical appropriateness. In a secondary analysis, increased age, black race, no previous surgery, lower level of chance locus of control, less trust of physicians, and less social support were associated with greater likelihood of surgery risk aversion.

In a 2004 study, blacks with colorectal cancer were more likely to refuse surgery when reasons for nonreceipt of surgery were analyzed using the SEER database. Concerns or fears about receiving a permanent stoma may affect patients’ willingness to pursue surgical consultation and/or follow-up with recommended surgery (which may explain why blacks with nonmetastatic rectal cancer were more likely to forgo radical resection and opt for local excision in a recent study from the NCDB). In a prospective cohort study of patients with early-stage lung cancer, the feeling that quality of life would be worse 1 year after lung cancer surgery was significantly higher among blacks than whites (42% vs 34%) and was associated with subsequent failure to undergo surgical resection.

Health care system factors

Access to care

Black-white differences in cancer care and outcomes may be partly explained by differences in access to care. In the Community Tracking Study Physician Survey, black Medicare beneficiaries were more likely to be cared for by physicians who were less well trained clinically and had more limited access to important clinical resources (eg, specialists, high-quality imaging, high-quality ancillary services, and nonemergency hospital admissions) than physicians who treated white patients. Lack of a regular source of health care was recently shown to be associated with underuse of surgical resection in patients with early-stage lung cancer, particularly among blacks.

Although underuse of surgery could also be related to lower referral rates for surgical consultation among blacks, the widely varying black-white differences in resection rates in patients with breast cancer, lung cancer, and colorectal cancer argue against systematic under-referral of blacks. In addition, a recent study showed that black race was a powerful, negative predictor of surgical resection even when the analysis was limited to patients who had received surgical consultation and been previously staged with mediastinoscopy.

To what extent does equal access to appropriate cancer care reduce black-white differences in treatment and outcomes? Dominitz and colleagues analyzed the effect of black race on surgery and adjuvant therapy in a cohort of 3176 colorectal cancer patients treated within the Veterans Administration (VA) equal access health care system. Irrespective of SES, blacks and whites had similar rates of surgery, radiation therapy, and chemotherapy (likely because referral patterns and payments were not barriers to care) and survival was similar across races. Equal health care coverage (ie, insurance), however, may not be sufficient to ensure equal access to care. Rogers and colleagues analyzed the effect of race on colorectal cancer outcomes in a population of elderly Tennesseans who were dually enrolled in both Medicaid and Medicare. Although there was no racial difference in overall mortality in a multivariate analysis controlling for comorbidity, stage, and treatment, only 86% of blacks received surgical therapy compared with 91% of whites ( P = .02).

Physician-patient communication

In a recent report from the cancer registry at the Henry Ford Health System in Detroit, black race had no apparent effect on the odds of being offered surgery for early-stage NSCLC (after controlling for comorbidity, pulmonary function, and tumor stage) but did have a negative effect on the rate at which surgery was declined by patients (OR 4.1; 95% CI, 0.34–0.55). In another study, black patients evaluated by a surgeon were more likely to have a negative recommendation for surgery (71.4% vs 67.0%, P <.05) and more likely to refuse surgery compared with whites (3.4% vs 2.0%, P = .013), suggesting that that miscommunication or bias during the patient-physician encounter was likely involved.

Several factors can influence patients’ decisions to undergo treatment. In a study of patients with advanced lung cancer, their caregivers, and medical oncologists, all 3 groups ranked the oncologist’s recommendation as the most important factor in decision making. Patients and caregivers ranked faith in God second (above the ability of treatment to cure their cancer), whereas physicians ranked faith last. Patients who ranked faith first were less educated and may not have fully understood the technical aspects or risks/benefits of their cancer treatments. Failure by physicians to acknowledge their patients’ strongly held beliefs might lead to unsatisfactory physician-patient interactions and suboptimal decision making. In a recent study of patients with early-stage lung cancer, patients who agreed with the statements, “faith alone cures disease” and “prayer will cure cancer,” were less likely to receive subsequent surgical resection. In addition, negative perceptions of physician-patient communication were associated with underuse of surgery across races.

In a recent analysis of audiotaped office visits between orthopedic surgeons and white versus black elderly patients, there were no significant differences in the content of various informed decision-making elements by race. When the encounters were evaluated for 4 relationship-building components of communication, however, coder ratings were significantly lower for responsiveness, respectfulness, and listening in visits with black patients. Not surprisingly, black patients were significantly less satisfied with the encounters and their surgeons, even after controlling for potential confounders.

Physician beliefs and biases

Persistent erroneous beliefs (reinforced by published reports) about the adverse effect of black race on surgical mortality and/or treatment efficacy may deter physicians from referring black patients with potentially curable cancers for surgical resection and/or adjuvant therapy. Race and SES can also affect physicians’ perceptions of patients and subsequent treatment recommendations. In a study of physicians from 8 New York hospitals, black patients of low SES were perceived more negatively by physicians during a postangiogram encounter. More specifically, blacks were more likely to be rated as less intelligent and educated, less likely to have poor social support, and more likely to be at risk for noncompliance.

Perceived racism by patients can also undermine the physician-patient relationship and ultimately result in mistrust and refusal to proceed with recommended treatments. In a survey of Medicare beneficiaries with localized breast cancer, blacks reported perceiving more ageism and racism in the health care system compared with whites, and ageism was associated with higher rates of mastectomy (compared with BCT) and omission of radiation after BCT. In a study of patients from North Carolina and South Carolina, 62% of patients with early-stage lung cancer (73% of blacks and 50% of whites) agreed or mildly disagreed that patients receive worse care due to their race, and endorsement of this belief was associated with failure to undergo surgical resection for lung cancer. Furthermore, increasing distrust in the health care system was associated with an almost 2-fold increase in failure to undergo surgery.

Factors underlying receipt of suboptimal cancer treatment

Physician knowledge and expertise

Black patients with nonmetastatic cancer may be more likely to be referred to less experienced surgeons with worse perioperative outcomes. In a study from South Carolina, approximately 50% and 60% of lobectomies and pneumonectomies, respectively, for lung cancer were performed by general surgeons, and the perioperative mortality after lobectomy was significantly higher among patients treated by general surgeons (5.3% vs 3.0%, P <.05). In a study analyzing the effect of surgeon volume versus hospital volume on outcomes after rectal cancer resection, surgeon volume was not associated with either 30-day mortality of rate of sphincter preservation. Surgeon volume was strongly associated with 2-year mortality, however, and was a stronger predictor of long-term survival than hospital volume.

It is possible that black patients are more likely to be referred to less experienced surgeons, who in turn, may be more likely to recommend more radical (and perhaps less palatable) surgery. Some studies have reported lower rates of BCT and sphincter preservation in blacks with breast cancer and rectal cancer, respectively. More recent work, however, has reported underuse of surgery but similar rates of sphincter preservation and adjuvant therapy among resected patients (suggesting that whatever barriers to care existed preoperatively, they did not seem to affect patients’ intraoperative or postoperative care).

Hospital factors

In a recent report from California, blacks were significantly more likely to undergo surgery at low-volume centers for 6 of 10 operations (including lung cancer resection and pancreatectomy), even when controlling for comorbidity, insurance status, rural residence, and proximity to low-volume, medium-volume, and high-volume hospitals. In addition, Medicaid patients (and uninsured patients) were also more likely to receive care at low-volume hospitals compared with Medicare patients. A recent analysis from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample also revealed that blacks who underwent lung resection were less likely to undergo surgery at high-volume hospitals and more likely to die postoperatively. These and other studies risk-adjusted outcomes using administrative data and may have underestimated the true extent of comorbidity among precisely those patients who would have been more likely to receive care at low-volume centers (ie, minority and underfunded patients). In contrast, a report from the VA-NSQIP detected no statistically significant association between procedure or specialty volume and 30-day mortality rate when outcomes were risk-adjusted using the more rigorous NSQIP methodology. “Evidence-based” hospital referral of selected patients to high-volume centers may not be practical, could exacerbate current racial disparities in access to care, and may inadvertently erode the level of surgical care at “low-volume” hospitals in rural and underserved areas. Recent work suggests that surgeon volume is a better predictor of rectal cancer outcomes than hospital volume and that the effect of hospital surgical volume may be negligible in patients who receive standard adjuvant therapy.

Hospital racial composition has also been shown to be associated with long-term outcomes in patients with breast cancer or colon cancer and attenuate the effect of individual patients’ race within hospitals. In a report of California Cancer Registry data, hospitals with a high Medicaid use rate (which cared for a disproportionate share of minority patients) had significantly higher 30-day and 1-year mortality rates compared with other hospitals. Taken together, these studies suggest that financial and/or resource constraints at the hospitals at which minorities are cared for may result in suboptimal care and disparities in treatment and outcomes. In a study of Medicare beneficiaries with cancer, black race was associated with worse 1-year and 3-year survival rates (largely due to later stage of disease at presentation and underuse of cancer-directed surgery); black race had no apparent adverse effect on outcomes, however, when the analysis was restricted to patients treated at NCI-designated cancer centers.

Moderators of receipt and quality of cancer treatment

Socioeconomic status

To some extent, race is a sociocultural construct and its apparent effect on health care access, use, and outcomes can be mediated and moderated by SES. In the NCI Black/White Cancer Survival Study, 26% of blacks lived at or below 125% of the poverty level income compared with only 9% of whites. Increasing income was associated with decreasing all-cause mortality, and controlling for poverty status eradicated the apparent, increased risk of cancer death among black patients with stage II-III colon cancer. In a recent study, black race was a powerful predictor of underuse of surgical resection in patients with rectal cancer, but its adverse was limited to patients living in poverty. Similarly, underuse of radiation after BCT was higher among blacks living greater distances from a cancer center or in areas of high poverty, whereas this effect was not seen in whites. Despite similar health care coverage, patients living in poverty may have worse access to financial and/or social resources needed to successfully negotiate the costs and inherent complexities of multidisciplinary cancer care.

Urban/rural status

Several studies have reported an association between rural residence and underuse of BCT (and adjuvant radiation after BCT) among women with invasive breast cancer. In a recent study, rural residence was associated with underuse of surgery across races, and black race had no apparent adverse effect on resection rates among rural patients. Rural women are less likely to have had a recent mammogram or breast examination compared with urban women (even when they report similar access to patient care) and tend to have more negative attitudes about breast cancer (despite having a similar knowledge base about the disease). Rural residents also experience limited access to health care (due to longer travel distances), fewer benefits (such as paid sick leave), fewer support services (such as childcare), and scant access to specialty physicians, including surgeons.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree