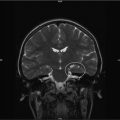

Fig. 20.1

Quality of life model. City of Hope Medical Center. http://prc.coh.org. Reprinted with permission [10]

It is important to note that the specific definition of QOL as it applies to children and their families/caregivers will change with time, as treatment changes, stages of disease progression/regression, age of patient, and numerous other factors influence QOL issues.

20.2.5 Pediatric Survivorship

The National Coalition for Cancer Survivorship and the National Cancer Institute give us this definition of survivorship:

“An individual is considered a cancer survivor from the time of diagnosis through the balance of his or her life. Family members, friends, and caregivers are also impacted by the survivorship experience and are therefore included in this definition” [10].

It is important to note that regardless of the duration of a child’s survivorship, the value and impact of quality palliative care techniques are profound, long term and far reaching. The essentials of palliative care—attention to physical pain and suffering, including existential distress; the inclusion of the family as a unit of care; and interdisciplinary care—are all relevant to and needed by the cancer survivor [11].

Survival after a cancer diagnosis often comes at a great price. Medical, psychological, social, and spiritual issues all impact the life of the child for as long as they live. Chronic pain, fatigue, anxiety, and social reintegration, as a result of survivorship will have their impact on the child’s quality of life. The application of palliative care strategies has been developed to address and reduce or eliminate those burdens. In general, the terms “supportive care” and “palliative care” may be used interchangeably. By definition, palliative care is not just for hospice and end of life care, but for any child suffering from a debilitating or chronic illness.

Unlike Hospice, the use of palliative care does not require a terminal illness diagnosis. On the contrary, palliative care (PC) is offered to patients undergoing curative treatment and who have long-term prognosis, such as cancer patients or those suffering from multiple sclerosis or cystic fibrosis. The PC model evolved from the traditional hospice perspective addressing QOL for those living with prolonged illness using an interdisciplinary team approach to care.

“Pediatric Palliative and/or Hospice care are recognized as the BLENDING of the two specialties, being both a philosophy and an organized method for delivering competent, compassionate, and consistent care to children with chronic, complex and/or life threatening conditions and their families. This merging of principles allows for increased access to care and ensures palliative treatments and support are available in all settings throughout the illness/dying trajectory” [12].

This “blending” of specialties could describe hospice as being the intensifying of PC as the child moves closer to death. Ideally children and families who live with chronic or progressive disease are receiving PC throughout the course and treatment of the child’s life, however long it may be. As they come closer to death and hospice is required, the child and family can be seamlessly transitioned to such programs.

20.2.6 Concurrent Care

In accordance with section 2302 of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, any Medicaid eligible recipient younger than 21 years of age and certified by a physician as having a life expectancy of six months or less may elect to concurrently receive hospice care in addition to curative treatment of the hospice related diagnosis [13]. This was passed by Congress on March 23, 2010. It is often referred to as the “2302 care provision.” This provision has greatly helped to change the ‘either hospice or curative treatment’ dilemma. Although this provides care for only those with Medicaid at this present time, several private insurances are now beginning to work with benefits to securing this care as well. The concurrent care provision is a vital piece of legislation that the pediatric hospice and PC communities have been championing for years. This will allow many children to receive all services that are related to the treatment of his or her life limiting illness. Providing palliative and hospice care services while they are receiving other disease-modifying treatments is a much-needed advance [4].

20.3 Purpose and Goals of Pediatric Palliative Care (PPC)

As described by the American Academy of Pediatrics, the goal of Pediatric Palliative Care (PPC) “is to add life to the child’s years, not simply years to the child’s life” [14]. The relief and prevention of suffering and enhancing quality of life along the illness trajectory for the children and their families is the primary purpose of PPC. The child and family are considered the unit of care, and their goals change frequently as children advance through disease survivorship or death. In order to meet the family’s changing needs, inter-disciplinary team (IDT) involvement is essential to bring consistency, continuity and compassion. The family and child direct the care with the guidance of the palliative team in collaboration with other primary service teams involved.

“Care is focused on enhancing the quality of remaining life by integrating physical, psychological, social, and spiritual aspects of care as defined by the family” [15]. Care is given in a manner that reflects the personal, emotional, cultural, and religious values, wishes, and goals of the child and family. Approach and interventions affirm life and neither hasten nor postpone death [16].

Within the IDT, the skill sets and support of members of differing disciplines and volunteers are critical to the care of the child and family as well as the effective functioning of the team itself. In the traditional hospice model the core disciplines include Medical Director (MD), Nurses, Social Workers, Chaplains, Home Health Aides, Bereavement Counselors and Volunteers. They are available 24 h a day, 7 days a week to respond to the needs of the child and family through providing pain and symptom management, emotional support, psycho-social needs, spiritual concerns and developing long-term goals of care.

In the broader application of PPC, other specialists such as Childlife, Pharmacists, Expressive Therapists, Dietitians, Psychologists, Teachers, Physical/Occupational/Respiratory and Speech Therapists may be included. All play a part in ensuring quality of life for the child and the family during illness, survivorship or the dying processes.

Figure 20.2 shows the traditional model of PC in the adult patient. Curative and palliative/hospice/supportive care are not concurrent. Oftentimes, families receive much needed palliative care too late. The “too little too late” access to care often results in needless suffering for the patient and their families. Figure 20.3 shows us the more progressive model. Curative therapies are pursued along with the introduction of PC from the time of diagnosis for adults with life threatening illness. It is vital to remember that some will have only a limited need for palliative care whereas others will need more intense involvement as the curative focus begins to change to supportive/end of life care. If the family has been introduced to PC early on during treatment the transition to support or hospice care is not so disruptive. A more seamless bridge prevents needless suffering and enhances quality of life for the patient and their family. The patient and family are more likely to view PC and even hospice care as not “losing hope” as much as “redefining hope.” If death occurs, for grief to progress and the tasks of mourning to be accomplished, bereavement support is essential to be provided.