PULMONARY SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

Pulmonary disease may be associated with a variety of signs and symptoms. The most common symptoms pointing to pulmonary pathology include dyspnea, cough, pleuritic chest pain, and hemoptysis.

Dyspnea is defined as an abnormally uncomfortable awareness of breathing

2 and is most often described as breathlessness or shortness of breath. Recently, dyspnea was defined by the American Thoracic Society (ATS) as “a subjective experience of breathing discomfort that consists of qualitatively distinct sensations that vary in intensity.”

3 Dyspnea is a very common presenting symptom of pulmonary disease. However, as delineated in

Table 30.1, dyspnea may also be indicative of cardiac disease, hematologic disease, neuromuscular disease, metabolic disease, deconditioning, and/or obesity, or it may be psychosomatic

in origin. A thorough history including acuity of onset, exacerbating factors such as exertion and positional change, and associated symptoms are vital in determining the etiology of dyspnea. Abrupt onset points to relatively acute processes such as pulmonary infection, pulmonary embolism (PE), and congestive heart failure (CHF). Subacute or chronic presentations of dyspnea are more likely to be indicative of underlying chronic bronchitis, emphysema, interstitial lung disease (ILD), or chronic CHF. Dyspnea may occur at rest or may only be apparent on exertion. In making an assessment of the severity of chronic dyspnea, it is important that the practitioner ask the patient “what are your usual daily activities?” and “what activities have you had to discontinue recently?” because patients often reduce activities to minimize discomfort.

4Evidence suggests that the perception of dyspnea may be blunted in the elderly. This may be due to a number of complex processes involving the mechanical properties of the lung and chest wall, central and peripheral chemoreceptors, neural input and output, and deconditioning. For example, there is a lower response to hypercapnic hypoxemia in the elderly, largely because of a decrease in carbon dioxide sensitivity.

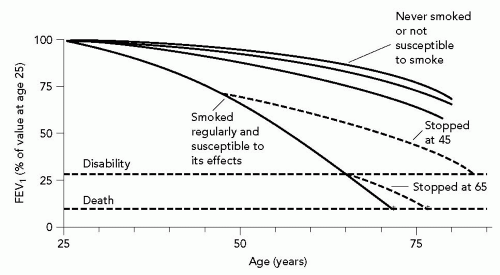

5 And, despite similar levels of decline in forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV

1), older subjects given methacholine bronchoprovocation testing noted less subjective discomfort compared to younger individuals. This may be due either to reduced number or activity of stretch receptors or to decreased perception of resistive respiratory loads.

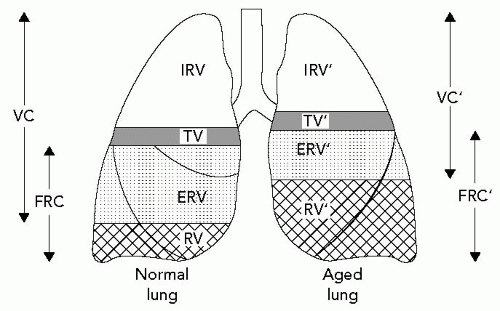

6A history of positional change eliciting or exacerbating dyspnea may be helpful in elucidating the underlying etiology. Orthopnea, or dyspnea in the supine position, is characteristic of CHF. It is usually related to gravitational elevation of pulmonary and venous capillary pressures and a reduction of vital capacity (VC). However, it may also be indicative of bilateral diaphragmatic paralysis and may occur in obstructive lung disease. Paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, like orthopnea, is usually indicative of CHF. It may also be present in chronic bronchitis because of pooling of secretions or in asthma because of circadian changes in airway obstruction. Platypnea, which occurs in the upright position, is most often associated with orthodeoxia, or oxygen desaturation when upright. Platypnea and orthodeoxia may occur because of changes in ventilation-perfusion (V/Q) matching or may be indicative of intracardiac shunt.

The underlying etiology of dyspnea in the elderly may usually be elucidated by means of a thorough history (including tobacco and occupational exposures), physical examination, and simple diagnostic testing. Initial testing should include a chest radiograph (CXR), electrocardiogram (ECG), and complete blood count (CBC). If a pulmonary cause for dyspnea is suspected, further investigation is indicated. This should include pulse oximetry or arterial blood gas (ABG) analysis and pulmonary function tests (PFTs). PFTs include spirometry, inspiratory and expiratory flow loops, lung volumes, and diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide (DLCO). If respiratory muscle weakness is suspected, maximal inspiratory and expiratory pressures should be obtained. If the cause of dyspnea remains unclear, echocardiography and, finally, cardiopulmonary exercise testing may help in differentiating between cardiac or pulmonary limitation and deconditioning.

1,

4Cough is a common symptom referable to the respiratory system. It is a physiologic mechanism for clearing and protecting the airway. It may be stimulated by a number of different processes, including airway irritation or inflammation, parenchymal disease, CHF, or medications. Cough is generally categorized as either acute or chronic on the basis of a duration of < or >3 weeks. In the overwhelming majority of cases, acute cough is related to either a viral or a bacterial upper respiratory tract infection. However, particularly in the elderly, acute cough may be a presenting manifestation of more serious illness such as pneumonia, aspiration, CHF, or PE.

7Studies have shown that chronic cough is usually due to one or a combination of four processes: Postnasal drip, cough-variant asthma, chronic bronchitis, or gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD).

8,

9 Other causes to consider in the elderly include bronchiectasis, CHF, ILD, bronchogenic lung cancer, postviral airway hyperreactivity, and recurrent aspiration.

7 An additional etiology that should be recognized in this population is angiotensinconverting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors. Approximately 5% to 20% of patients placed on ACE inhibitors will develop a dry cough. This is a class effect of these antihypertensive medications and is most likely related to the accumulation of the inflammatory mediators bradykinin or substance P, both of which are degraded by ACE. The development of cough is idiosyncratic and is not dose related. The time course may be quite variable, ranging from several hours to even months after initiation of ACE inhibitors. After discontinuing the medication, the cough generally resolves within 4 days.

10Evaluation of chronic cough should begin with a complete history and physical examination, as well as a CXR. If the CXR is normal, and nothing in the history and physical points to a diagnosis, the next most useful step is a methacholine challenge test to assess for bronchial hyperreactivity (BHR).

8 GERD may be silent. Therefore, if another cause of chronic cough cannot be found and treated, prolonged esophageal pH monitoring should be considered.

11 Some patients will be found to have more than one diagnosis. Therapy should be directed toward the underlying pathophysiologic mechanism of the cough. Specific therapy has been shown to be effective in patients compliant with the therapeutic regimen in 97% to 98% of cases.

8,

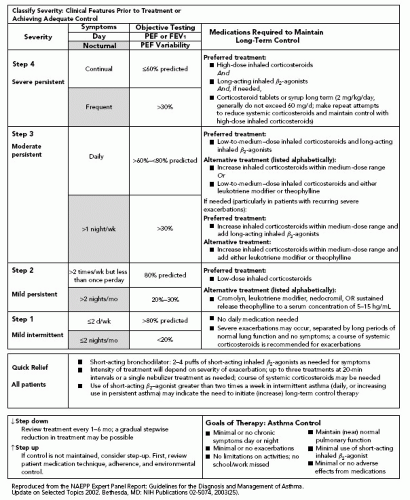

9 Patients with chronic bronchitis, asthma, and postviral airway hyperreactivity respond to inhaled bronchodilators and corticosteroids; those with postnasal drip respond to decongestants and nasal steroid preparations and those with GERD to

histamine-2 (H

2) blockers and proton pump inhibitors. Symptomatic treatment with antitussive agents such as dextromethorphan, and narcotics such as codeine is useful to supplement specific therapy, but is ineffective alone.

Pleuritic chest pain is most often sharp but may also be described as dull, achy, or a “catching” sensation. Characteristically, it worsens with deep inspiration, cough, or positional change. Pleuritic pain originates in the parietal pleura, which has extensive pain fiber innervation; the visceral pleura does not. Pain is usually relatively well localized over the area of involvement. However, if the diaphragmatic parietal pleura is affected, pain may be referred to the shoulder.

12 Inflammation in the peripheral lung parenchyma may spread to the visceral and then parietal pleura, causing pleuritic pain. Some of the most common causes of pleuritic chest pain include pneumonia, PE, pneumothorax, pleuritis due to acute viral infection or collagen vascular disease, pericarditis, and radiation pneumonitis.

Hemoptysis may be noted by the patient as ranging from blood-streaked sputum to the expectoration of gross blood. If massive (defined as >200 to 600 mL in a 24-hour period, depending on the author), it represents a medical emergency requiring hospitalization and immediate evaluation by a pulmonologist and/or thoracic surgeon.

13 Studies performed in the 1940s to 1960s found that the most frequent causes of hemoptysis included bronchiectasis, bronchogenic carcinoma, and tuberculosis (TB). More recently, bronchitis has become one of the most frequent etiologies of hemoptysis in developed countries. In contrast, TB is much less common.

14,

15 Table 30.2 lists some of the more common etiologies of hemoptysis.

Evaluation should begin with a detailed history and physical, ruling out other sources of bleeding such as the upper respiratory or gastrointestinal tracts. Duration and amount of hemoptysis, smoking history, and features suggestive of the presence of bronchitis or a pulmonary parenchymal infection should be elicited. The most important diagnostic test is the CXR. Additional testing to consider includes a CBC, coagulation profile, renal function studies, and urinalysis. If the CXR is abnormal, it may be helpful in elucidating the underlying etiology. If normal or without localizing findings, studies have shown that independent risk factors for occult carcinoma include age >40 years, smoking history of >40 pack-years, and duration of hemoptysis of >1 week.

15,

16,

17If hemoptysis is not massive, <1 week in duration, occurs in the setting of acute bronchitis, and if CXR is normal, further workup is not usually necessary, provided there is resolution with appropriate antibiotic therapy. However, if there is an abnormal finding on CXR, hemoptysis is massive, persists for >1 week, occurs in a setting inconsistent with acute bronchitis, or two or more of the above patient risk factors for carcinoma are present, pulmonary or thoracic surgery consultation is advised for further evaluation.

15,

16,

17 Fiberoptic bronchoscopy and/or high-resolution computed tomography scanning are the next steps in evaluation, depending on the clinical setting, and may provide complementary information.

18,

19 Further evaluation is particularly important in the geriatric population, which is at higher risk for carcinoma, especially those individuals with a significant history of smoking or second-hand exposure.