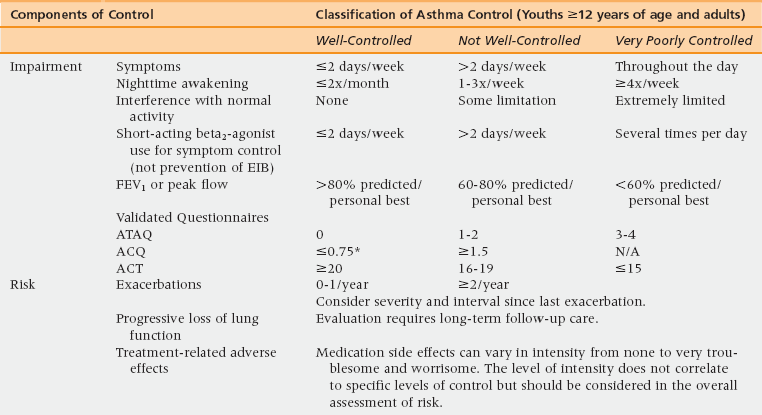

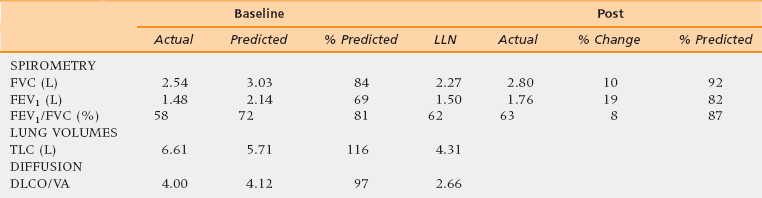

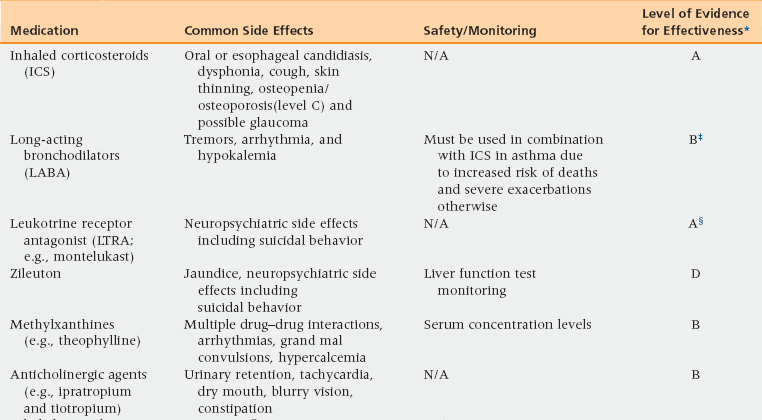

48 Pulmonary Physiology and Aging Assessment of Pulmonary Diseases Based on Signs and Symptoms Common Obstructive Pulmonary Diseases in the Older Adult Restrictive Pulmonary Diseases in the Older Adult Objective Evaluation of Pulmonary Diseases Methacholine Bronchoprovocation Challenge Test Peak Expiratory Flow Rate Monitoring Fractional Exhaled Nitric Oxide Measurement Upon completion of this chapter the reader will be able to: • Recognize and describe the changes in pulmonary physiology among the aging population. • Identify and differentiate the signs and symptoms of pulmonary diseases in the geriatric population with multiple comorbidities. • Define the differences between asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and restrictive lung diseases in terms of diagnosis and management. • Demonstrate the understanding of interpretation and the value and limitations of diagnostic tests for pulmonary diseases. The respiratory system, induced by chronic low-grade inflammation and stress-mediated imbalances, undergoes anatomic, physiologic, and immunologic changes with age. Studies have shown that the rapid rate of decline of peak aerobic capacity has significant repercussions with regard to functional independence and quality of life, in both healthy older persons and in those with disease-related deficits.1 With the number of people in the United States older than age 65 years estimated to reach 71 million by 2030, a thorough understanding of the natural progression of age-related changes in the respiratory system is necessary.2 The respiratory system comprises mainly the rib cage, diaphragm, and lungs. Osteoporosis may result in reduced height of the thoracic vertebrae with subsequent kyphosis. Kyphosis reduces the ability of the thoracic cage to expand during inspiration and places the diaphragm at a mechanical disadvantage to generate effective contraction.2 Similarly, age-related decline in diaphragmatic strength related to muscle atrophy and reduction in the fast-twitch fibers can result in respiratory fatigue and eventual ventilatory failure.3 In addition, degradation of the elastic fibers around alveolar ducts, and loss of elastic recoil of the lungs and the supporting lung parenchyma, lead to air trapping from early closure of the small airways and can cause hyperinflation with increased residual volume and functional residual capacity.4,5 Age-related decreased ability of the respiratory center in the medulla oblongata to detect hypoxia or hypercapnia results in a diminished ventilatory response in cases of aggravated airway obstruction.5 Furthermore, decreased perception of bronchoconstriction and diminished physical activity with age can result in a reduced awareness of respiratory disease and thus delayed diagnosis and treatment initiation. Given these changes a heightened awareness of pulmonary disease is necessary among primary care physicians to diagnose and initiate treatment early. As in any other age group, the presence of episodic symptoms of airflow obstruction or airway hyperresponsiveness must be documented to establish a diagnosis of obstructive lung diseases in the geriatric population.6 These symptoms include but are not limited to the presence of wheezing, chest tightness, cough with or without mucus production, or shortness of breath with or without exertion. Such information can be obtained via a detailed medical history and a physical examination focusing on the upper and lower respiratory tract and the chest. Table 48-1 lists the most commonly seen differential diagnosis of pulmonary diseases in older adults with these symptoms. TABLE 48-1 Differential Diagnosis for Pulmonary Diseases in Older Adults Congestive heart failure Coronary artery disease Pulmonary embolus Mechanical obstruction caused by mass or enlarged lymph nodes Pulmonary infiltrated with eosinophilia/eosinophilic bronchitis Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA) Churg-Strauss vasculitis Obliterative bronchiolitis Post-nasal drip Vocal cord dysfunction Gastro-esophageal reflux disease (GERD) Mechanical aspiration Tracheomalacia (as a result of underlying rheumatologic diseases [e.g., relapsing polychondritis]) Modified from Expert Panel Report 3 (EPR-3): Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of asthma-summary report 2007. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2007;20(5 Suppl):S94-138. When evaluating a patient with a chronic cough (lasting more than 6 weeks), the obstructive and restrictive pulmonary diseases and cough variant asthma must be considered. In addition, the differential includes cough caused by postnasal drip, medications such as angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, and gastroesophageal reflux disease. Coughing with hoarseness of the voice may also be a sign of vocal cord dysfunction (VCD). VCD, also referred to as paradoxical vocal cord motion (PVCM), is a condition where there is paradoxical adduction of the anterior portion of the vocal cords during inspiration. VCD can be diagnosed based on videostroboscopy. Flattening of the inspiratory loop on spirometry may also be seen in VCD. TABLE 48-2 Asthma is a chronic inflammatory disorder characterized by variable and recurring symptoms of airway hyperresponsiveness, bronchoconstriction, and airway inflammation. More than 22 million Americans have asthma, with the incidence being 1 in 1000 per year among adults and older adults.6,7 The prevalence of asthma in the geriatric population is estimated to be 10%. Approximately 3.1 million Americans older than age 65 years have asthma.6,7 Asthma in the elderly can present as a heterogeneous disease at any age with varying degree of severity. Unlike in the young, when asthma begins later in life it is rarely an extrinsic (i.e., an IgE-mediated process) or familial.7 Triggers may include indoor and outdoor allergen exposure, pollutants, molds, endotoxin, and latent viral and bacterial infections. These triggers may induce bronchoconstriction, airway inflammation, and edema, which are hallmark features of the airway obstruction that causes asthma.6,7 Approximately 15% of U.S. adults with asthma have asthma attributable to occupational exposures and this number continues to rise.8,9 Asthma in the elderly may often have an irreversible component owing to three main factors, unrelated to the pack-years of smoking.10 The first factor is that more severe disease can lead to airway remodeling causing diffuse thickening of the basement membrane. This remodeling and hypertrophy of smooth muscles and submucosal glands in some bronchial segments results in irreversible obstruction. The second factor leading to fixed obstruction is the time and age of onset of disease. Asthma may begin as early as the fourth or fifth decades of life. Asthma can go undetected and untreated for several years, leading to an accumulation of pulmonary damage. A third factor is the coexistence of underlying COPD or pulmonary fibrosis.7 Patients may have more than one pulmonary disease; therefore a mixed defect or partial reversibility may be a clue. The later section of this chapter that discusses objective evaluation of pulmonary diseases gives detailed information on how to evaluate a patient with signs and symptoms suggestive of asthma. Briefly, all patients with suspected asthma should be evaluated to confirm the objective diagnosis of asthma. Because asthma is a disease of reversible airflow limitation, confirmatory tests would include spirometry with a reversible obstructive defect or methacholine bronchoprovocation challenge test with a drop in forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) of 20% or more from baseline at any concentration of methacholine less than 4 mg/mL. The Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) guidelines identify four components of asthma care: (1) development of doctor–patient relationship; (2) identification and reduction of exposure to risk factor; (3) assessment, treatment, and monitoring of asthma; and (4) managing asthma exacerbations.11,12 Development of a partnership between the physician and patient leads to effective management of asthma that provides comprehensive education in terms of proper use of medications. Education should include monitoring of skills needed to use aerosol medications, understanding differences between controller and reliever medications, recognizing worsening of asthma symptoms with or without peak expiratory flow rate (PEFR) monitoring, Asthma Action Plan (see Web Resources), and seeking medical advice when appropriate.11 Physicians should also address any patient concerns regarding asthma, the medications, or management. The second component of comprehensive asthma care involves identification of and then control of exposure to risk factors, such as cigarette smoke (active and passive), drugs (nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs [NSAIDs], beta-blockers, etc.), occupational sensitizers (diisocyanates, trimellitic anhydride, sulfur dioxide fumes, etc.), and sensitization to aeroallergens. Patients with moderate to severe asthma should be advised to receive the influenza vaccine yearly.12 Avoidance measures improve control of asthma and reduce the need for medications. The third component of asthma care is assessing asthma severity and control, treating to achieve control, and monitoring to maintain control. The distinction between severity and control represents a major change in the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) guidelines updated in 2007. Assessment of asthma severity is based on frequency of asthma-type symptoms, nocturnal awakening, and use of a short-acting beta2-agonist (SABA2) along with degree of interference with daily activity, and lung function measurements (using FEV1 and FEV1/FVC [forced vital capacity]) (Figure 48-1). Asthma severity grading should be used to initiate asthma therapy. Based on the level of severity, asthma can be categorized into intermittent, mild-persistent, moderate-persistent, or severe-persistent.6,11,12 Asthma control should then be assessed at all subsequent visits to minimize risk and maximize function (Table 48-3). Assessment of asthma control is also based on the aforementioned factors, and is categorized into well controlled, not well controlled, and very poorly controlled.6,11,12 Figure 48-1 Classification of asthma severity. EIB, exercise induced bronchoconstriction. (Reproduced from Expert Panel Report 3 [EPR-3]: Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of asthma-summary report 2007. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2007;120[5 Suppl]:S94-138.) As an aid in the assessment of control, an asthma control questionnaire such as the Asthma Control Test (ACT) can be used on follow-up visits for evaluation of asthma control. The ACT is a valid and reliable measure of changes occurring in asthma control. A score lower than 19 out of 25 is considered a marker of poor control. (The Preventive Maintenance section later in the chapter discusses the medications used in the management of chronic asthma.) The fourth component of asthma care is managing asthma exacerbations, acute or subacute episodes of worsening of asthma-related symptoms characterized by decreases in expiratory flow. Risk factors for asthma-related death from exacerbations include previous history of severe exacerbation needing intubation or an intensive care unit admission, two or more hospitalizations or three or more emergency room visits in the past year, difficulty perceiving airway obstruction, lower socioeconomic status, and the presence of other comorbid conditions. Worsening PEFR at home can help identify early signs of an exacerbation and can help monitor response to therapy used to treat an exacerbation. Adjusting medications, by increasing the short-acting beta agonist (SABA) or adding a short course of oral systemic corticosteroids, is recommended. Doubling the dose of inhaled corticosteroids (ICSs) is generally not effective. A drop in the PEFR of 40% to 69% from the patient’s personal best is a marker of a moderate-severity asthma exacerbation that requires an in-office visit or emergency department visit and the use of an oral steroid. A drop in the PEFR of more than 40% from the patient’s personal best will likely require hospitalization. Ongoing therapy for asthma can be tailored accordingly to the NHLBI guideline’s six-step treatment approach for all patients 12 years of age or older with asthma (Figure 48-2).6 Intermittent asthma can be managed with the use of a SABA as needed. For all categories of persistent asthma, ICS is the preferred first line of therapy for the long-term control, especially in those with more severe asthma.11,13 Additional therapies include long-acting beta agonist (LABA), leukotrine receptor antagonist (LTRA: montelukast, zileuton), methylxanthine derivatives (theophylline), anticholinergic agents (ipratropium or tiotropium), cromones (cromolyn), or anti-IgE therapy (omalizumab). Addition of these therapies to ICS treatment can be considered on a case-by-case basis based on severity, lack of control, and presence of other comorbid conditions (Table 48-4). However it should be noted that in 2010 the U.S. Food and Drug Administration indicated that the addition of LABAs to the therapeutic regimen of patients with poorly controlled asthma could worsen outcomes, particularly in African Americans and those not using ICSs. Therefore, a LABA should not be added until the patient has tried a medium-dose ICS first. Patients with severe asthma whose symptoms are not well controlled with high-dose ICS or combination therapy may require oral corticosteroids for maintenance of asthma control. If possible, an alternate day regimen may help reduce the systemic risks of oral corticosteroids as listed in Table 48-4 while still maintaining control (referred to as the minimal effective dose). Figure 48-2 Stepwise approach for managing asthma. TABLE 48-4 Medications for the Management of Asthma in the Older Adult Table modified from: Expert Panel Report 3 (EPR-3): Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma-Summary Report 2007. J Allergy Clin Immunol, 2007. 120(5 Suppl): p. S94-138.

Pulmonary disease

Pulmonary physiology and aging

Assessment of pulmonary diseases based on signs and symptoms

Common obstructive pulmonary diseases in the older adult

Asthma

Definition and epidemiology

Diagnosis

Treatment

EIB, exercise induced bronchoconstriction. (Reproduced from Expert Panel Report 3 [EPR-3]: Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of asthma-summary report 2007. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2007;120[5 Suppl]:S94-138.)

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree