All psychosocial care is palliative in nature. Attention must be directed to the realities of one’s life within their unique social context in order to maximize internal resources, activate external support systems, and focus on the dignity and quality of life (QOL). Psychosocial care within palliative care programs seeks ongoing evidence of effectiveness and clear benefit to patients, caregivers, and the healthcare system. Palliative care is provided by interdisciplinary teams of compassionate experts, but if there is no team in place, true whole-patient-centered care is not possible (

1). The creation of palliative care in hospitals has dramatically increased over the past 5 years (

2); however, institutional support and integration into standard clinical care is still far less than is desirable.

Psychosocial concerns, to varying degrees, based on context and predisposition, are always at the core of the cancer experience. Life-limiting illness and related demands are always stressful. However, there are also opportunities for the repairing and deepening of relationships and to live a meaningful life. In the absence of moderate to severe distress caused by physical symptoms, such as pain, nausea, and difficulty in breathing, the psychosocial and spiritual aspects of a person’s identity and life become paramount. The psychosocial aspects of a person’s life are what give them a sense of being vital human beings within a social context for living with a life-threatening illness with the possibility for emotional growth and transcendence.

Despite significant progress in research and treatments, the diagnosis of cancer creates fear and turmoil in the lives of every patient and family. In many respects, cancer generates a greater sense of dread than other life-threatening illnesses with similar prognoses (

3). Some studies have found that patients with cancer are sicker and have more symptoms than patients without cancer in the year before death, and most often, it is easier to predict the course of the illness (

4). Yabroff and Youngmee (

5) documented that many noxious physical and psychological symptoms are prevalent in the year after diagnosis, after disease-directed treatments have ceased, regardless of prognosis.

Frequently, the greatest concern of patients with cancer is not death, pain, or physical symptoms, but rather the impact of the disease on their families (

6). People see themselves as imbedded in a larger social construct that gives them a sense of place and meaning. For most cancer patients, it is the family that is at the most basic core of that identity. According to the World Health Organization (

7), family refers to those individuals who are either relatives or other significant people as defined by the patient. Healthcare professionals must acknowledge the role of the family to maximize treatment outcomes. If the family is actively incorporated into patient care, the healthcare team gains valuable allies and resources. Families are the primary source of support and also fill in the caregiving roles for persons with cancer. Of note, men are taking a greater responsibility for the care of seriously ill spouses, but women still comprise most of the individuals who serve in these caregiving roles (

8,

9).

Although access to ongoing palliative care could potentially provide needed support for both patient and family, resources for palliative care remain consistently limited. In the United States most palliative care is still invested in hospice programs, but only the median length of service for hospice patients continues at 3 weeks or less (

10,

11). Furthermore, a discussion concerning a referral to hospice can seem quite sudden, and the patient and family can experience this transition as rejection. Despite the sobering survival statistics for many cancers, relatively few hospitals have truly developed a continuum of cancer care, which informs patients and families that most antineoplastic therapy in advanced disease is palliative and not curative. In particular, this is true for patients with cancer who enroll in phase I and II clinical trials (

12). This is significant given that most patients with cancer overestimate the probability of long-term survival (

13). At present, patients and family members enter hospice care, which is the primary resource for comprehensive palliative care services, and attempt to accept that prolongation of life is no longer the goal of care. In addition to the shift in the focus from cure to care, the patient and family experience the loss of the healthcare team with whom trust has been imbued over months and sometimes many years. The loss occurs simultaneously at multiple levels. Although palliative care at the end of life should be a time of refocusing and resolution, the hospice referral process may cause an iatrogenic crisis rather than comfort. But even when patients are not transferred to an external setting trauma is common. This is especially true of patients who are admitted to ICUs where the caregivers of deceased patients all too frequently report symptoms (up to 20%) of posttraumatic distress disorder from the experience many years after the

death (

14). Consequently, the focus of care for patients with advanced disease needs to be the early identification of vulnerability, such as significantly elevated distress, that is followed by evidence-based psychosocial interventions.

PSYCHOLOGICAL RESPONSES TO ADVANCED CANCER

The psychological impact of advanced cancer and its management is directly influenced by the interactions among the degree of physical disability, the severity of symptoms, the internal resources of the patient, the level of social support, the intensity of the treatment, side effects and other adverse reactions, and the relationship with the healthcare team. The degree of physical distress placed on any individual and the inevitable drive to give meaning to the experience is the core from which the psychosocial concerns arise. At present, active support for aspects of palliative care is sporadic at best, especially in non-academic medical settings (

15).

Adaptation to advancing disease begins with an appraisal of the extent of perceived harm, loss, threat, and challenge that this experience generates. In many respects, this appraisal is linked to the intensity and quality of the patient’s emotional response. Emotional regulation is at the core of coping and has significant implications for maintaining a sense of direction and control. Overall, this primary appraisal, efficiency of emotional regulation, and definition of the meaning of advanced cancer result in an assessment of the extent of the potential harm and threat, which then requires a secondary appraisal to be made. In this secondary level, patients must assess their personal (internal) and social (external) resources necessary to begin to address the demands and problems associated with advanced cancer. This process can be significantly influenced by the patient’s ability to maintain emotional regulation (

16).

In addition, two salient continuums related to patient and family adaptation must be considered. The level of psychological distress forms the first continuum and the second consists of the predictable and transitional phases of the disease process. Patients with a preexisting high level of psychological distress can experience significant difficulty with any attempt to adapt to the stressors associated with a cancer diagnosis. Although most patients experience significant distress at the time of their diagnosis, most patients gradually adjust during the following 6 months (

17). Evidence indicates that the best predictor of positive adaptation is the psychological state of the patient with cancer before the initiation of any therapeutic regimens (

18). Although clinical experience would clearly indicate that the health system can influence the ability of patients and their families to adapt, literature to support this premise empirically is not available. Clinically, it is quite evident that hospitals do a very poor job at key (very common and entirely predictable) transition points in the care of seriously ill patients. But, there are now strong data that indicate palliative care for specific groups of cancer patients with advancing disease can extend both QOL and length of life (

19).

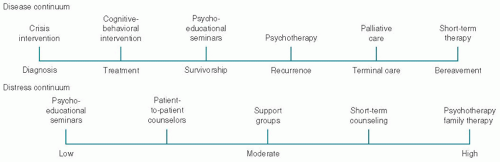

Figure 50.1 details potential interventions along the disease and distress continuums. The level of psychological vulnerability also falls along a continuum from low to high distress and should guide this selection of interventions (

20). In addition, problem-solving interventions have been demonstrated to reduce distress among patients with cancer as well as among family members (

21,

22). Prevalence studies demonstrate that one of every three newly diagnosed patients (regardless of prognosis) needs psychosocial or psychiatric intervention (

23,

24,

25,

26). As disease advances, a positive relationship exists between the increase in the occurrence and severity of physiologic symptoms and the patient’s level of emotional distress and overall QOL. For example, a study of 268 patients with cancer having recurrent disease observed that patients with higher symptomatology, greater financial concerns, and a pessimistic outlook experience higher levels of psychological distress and lower levels of general well-being (

27).

In an effort to establish early identification of patients at high risk for poor adaptation, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) developed guidelines for the

management of psychological distress among cancer patients across the disease continuum. The NCCN described distress in a manner consistent with the focus and goals of palliative care, as an experience that can be psychological, social, or spiritual which interferes with one’s ability to manage or problem-solve in relation to the diagnosis, treatment, side effects, and symptoms associated with cancer (

28). These guidelines provide a framework for the development and implementation of psychosocial interventions based on the perspectives of psychiatry, social work, psychology, nursing, and pastoral care. Psychosocial screening serves as the mechanism to identify patients at higher levels of risk in order to provide interventions at a much earlier point in time. These guidelines can be accessed at www.nccs.org.

If distress levels can be identified through techniques such as psychosocial screening, patients can then be introduced into supportive care systems earlier in the treatment or palliative care process. In fact, nationally and internationally, a number of investigators have successfully implemented robust biopsychosocial screening initiatives as part of the standard of clinical care in cancer setting (e.g., J. Zabora, M. Loscalzo, B. Bultz, and A. Mitchell). All of these screening programs use instruments that include psychological and physical symptoms, as well as social, spiritual, and practical concerns (

28). Some of these programs use automated referrals or triages, provide educational information, and send clinical summary alerts to the physician and team during the clinical encounter (

29). Of significant importance, the influential Institute of Medicine report in 2007, Cancer Care for the Whole Patient: Meeting Psychosocial Health Needs, has endorsed biopsychosocial screening as the minimum standard of quality cancer care (

30). Subsequently, the American College of Surgeons (ACoS) has established a new standard that requires screening for distress in ACoS accredited programs. In Canada, distress has been endorsed as the sixth vital sign (

31).

Accordingly, any attempt to identify vulnerable patients and families in a prospective manner is worthwhile. Screening techniques are available through the use of standardized instruments that are able to prospectively identify patients and families that may be more vulnerable to the cancer experience (

32,

33). Preexisting psychosocial resources are critical in any predictive or screening process. In one approach, Weisman et al. (

34) delineated key psychosocial variables in the format of a structured interview accompanied by a self-report measure (

Table 50.1). However, in hospitals, clinics, or community agencies, which provide care to a high volume of patients and family members, a structured interview by a psychosocial provider is seldom feasible or even warranted. Consequently, brief and rapid methods of screening are necessary. Brief screening techniques that examine components of distress, such as anxiety or depression, can be incorporated into the routine clinical care of the patient. But only screening for psychiatric symptoms is not adequate. Just as cancer patients should not have to be dying to receive the full suite of palliative care services, patients and their families should not have to manifest psychiatric symptoms to receive psychosocial support. Early psychosocial interventions may be less stigmatizing to the patient, and more readily accepted by patients, families, and staff if screening identifies the management of distress as one component of comprehensive care (

35). Screening is also a cost-effective technique for case identification in comparison to an assessment of all new patients (

36). Although screening for distress and disease-related problems have received much attention recently, there are relatively few screening programs in place, even in comprehensive cancer centers (

37). The City of Hope National Medical Center and NCI-designated Comprehensive Cancer Center in Duarte, California, is one of the few cancer programs that is screening patients with cancer for common problems and related distress. A fully automated touchscreen system (

SupportScreen) has been in place since 2009 and has been licensed to a number of hospitals (

29).

SupportScreen provides an opportunity for the patients (and in some clinics family caregivers) to input their own information (in English and Spanish) relating to

immediate psychological and physical symptoms as well as social, spiritual, and practical concerns. Patients are able to indicate the degree of distress they are experiencing as well as the kind of assistance they are seeking from the healthcare team. Personalized educational sheets and resources are also provided, all in real time during the actual clinical encounter. The physician and healthcare team also automatically receive paper and electronic clinical alerts right before they meet with the patient. This technology has been very well received by physicians and staff, patients (of all adult ages), and family members. The experience at the City of Hope and other hospitals has demonstrated that patients prefer touchscreen technology to either paper and pencil and to a personal interviews and provide more personal information in this medium (

38). The items on the screening instrument have also been tailored for individual clinics by medical specialty. The implications for the integration of palliative care into the standard of clinical care are of major importance. Many of the domains that relate to serious illness are emotionally laden and many physicians and healthcare providers lack the time, training, or inclination to open conversations that are essential to the psychological well-being of patients and their concerned family members. In this instance, it is quite evident that this technology and biopsychosocial content have the potential to transform the clinical encounter and the relationship between patients and their healthcare providers.

For each of the problems listed, a triage plan is in place and can be accessed during the clinical visit by the physician, nurse, or social worker. The social worker assesses the potential need for referrals to psychology and psychiatry. Not surprisingly, the 10 most common problems in rank order manifested by the first 300 patients with cancer at the City of Hope were fatigue (feeling tired), fear and worry about the future, finances, pain, feeling down, depressed or blue, being dependent on others, understanding my treatment options, sleeping, managing my emotions, and solving problems due to my illness. Of particular note, although pain was not the most frequently endorsed problem, it was the most emotionally distressing.

Standardized measures of psychological distress can differentiate patients into low, moderate, or high degrees of vulnerability. Patients with a low or moderate level of distress may benefit from a psychoeducational program, which can enhance adaptive capabilities and problem-solving skills; high distress patients possess more complex psychosocial needs that require brief therapy or family therapy along with psychotropic drug therapy for the patient. For some patients ongoing mental health services are essential, whereas other patients may require assistance only at critical transition points. Clinical practice suggests that virtually all patients could benefit from some type of psychosocial intervention at some point along the disease continuum, especially at the end of life. Psychosocial interventions include educational programs, support groups, cognitive-behavioral techniques, problem-solving therapy or education, and psychotherapy (

39). To further facilitate the process of screening, the brief standardized instruments have been developed to create greater ease of administration and scoring and to develop gender-based norms (

40,

41).

The second continuum relates to the predictable phases of the disease process. This disease continuum extends from the point of diagnosis to cancer therapies and beyond. Across this continuum, patients acquire experiences, knowledge, and skills that enable them to respond to the demands of their disease. The needs of a newly diagnosed patient with intractable symptoms differ significantly from a patient who has advanced disease and no further options for curative treatments.

The patient and family may be supported throughout the illness process and the family requires continuing support following the death of the patient. At times families are overwhelmed by the illness and as a result are unable to effectively respond. For some families, a death may represent a major loss of the family’s identity and may paralyze the family’s coping and problem-solving responses. Failure to respond and solve problems leads to a lack of control and may generate a significant potential for a chronic grief reaction (

42). Although the disease continuum consists of specific points,

Table 50.2 identifies a series of predictable and relevant crisis events and psychosocial challenges that occur as patients and families confront advanced disease.