Psychosocial Consequences of Advanced Cancer

James R. Zabora

Matthew J. Loscalzo

All psychosocial care is palliative in nature. Attention must be directed at the realities of one’s life within their unique social context in order to maximize internal resources, activate external support systems, and focus on the dignity and quality of life (QOL). Psychosocial care within palliative care programs seeks ongoing evidence of effectiveness and clear benefit to patients, caregivers, and to the health care system. However, institutional support for these approaches always seems to be less than desirable.

Psychosocial concerns, to varying degrees, based on context and predisposition, are always at the core of the cancer experience. Life limiting illness and related demands are always stressful. However, there are also opportunities for the repairing and deepening of relationships and to make a meaningful contribution. In the absence of moderate to severe distress caused by physical symptoms, such as pain, nausea, or difficulty in breathing, the psychosocial and spiritual aspects of a person’s identity and life become paramount. The psychosocial aspects of a person’s life are what give them individuality and a context for living with a life-threatening illness.

Despite significant progress in research and treatments, the diagnosis of cancer creates fear and turmoil in the lives of every patient and family. In many respects cancer generates a greater sense of dread than other life-threatening illnesses with similar prognoses (1). Some studies have found that patients with cancer are sicker and have more symptoms than patients without cancer in the year before death, and most often, it is easier to predict the course of the illness (2).

Frequently, the greatest concern of patients with cancer is not death, pain, or physical symptoms, but rather the impact of the disease on their families (3). According to the World Health Organization (4), family refers to those individuals who are either relatives or other significant people as defined by the patient. Health care professionals must acknowledge the role of the family to maximize treatment outcomes. If the family is actively incorporated into patient care, the health care team gains valuable allies and resources. Families are the primary source of support and also fill in the caregiving roles for persons with cancer. Of note, women comprise most of the individuals who serve in these caregiving roles (5, 6).

Although access to ongoing palliative care could potentially provide needed support for both patient and family, resources for palliative care are consistently limited. In the United States most palliative care is invested in hospice programs, but only one-third of all patients with cancer receive formal hospice care, often only in the final days of life (7, 8). Furthermore, a discussion concerning a referral to hospice can seem quite sudden, and the patient and family can experience this transition as rejection. Despite the sobering survival statistics for many cancers, relatively few hospitals have developed a continuum of cancer care, which informs patients and families that most antineoplastic therapy is palliative and not curative. In particular, this is true for patients with cancer who enroll in Phase I and II clinical trials (9). This is significant given that most patients with cancer overestimate the probability of long-term survival (10). At present, patients and family members enter hospice care, which is the primary resource for comprehensive palliative care services, and attempt to accept that prolongation of life is no longer the goal of care. In addition to the shift in the focus from cure to care, the patient and family experience the loss of the health care team with whom trust has been imbued over months and sometimes many years. The loss occurs simultaneously at multiple levels. Although palliative care at the end of life should be a time of refocusing and resolution, the referral process may cause an iatrogenic crisis rather than comfort.

Psychological Responses to Advanced Cancer

The psychological impact of advanced cancer and its management is directly influenced by the interactions among the degree of physical disability, internal resources of the patient, the level of social support, the intensity of the treatment, side effects, and other adverse reactions, and the relationship with the health care team. The degree of physical distress placed on any individual and the inevitable drive to give meaning to the experience is the core from which the psychosocial concerns arise.

Adaptation to this phase of the illness begins with an appraisal of the extent of harm, loss, threat, and challenge that this experience generates. In many respects, this appraisal is linked to the intensity and quality of the patient’s emotional response. Overall, this primary appraisal and definition of the meaning of advanced cancer results in an assessment of the extent of the potential harm, which then requires a secondary appraisal to be made. In this secondary level, patients must assess their personal (internal) and social (external) resources necessary to begin to address the demands and problems associated with advanced cancer (11).

In addition, two salient continuums related to patient and family adaptation must be considered. The level of psychological distress forms the first continuum and the second consists of the predictable and transitional phases of the disease process. Patients with a preexisting high level of psychological distress can experience significant difficulty with any attempt to adapt to the stressors associated with a cancer diagnosis. Although most patients experience significant distress at the time of their diagnosis, most patients gradually adjust during the following 6 months (12). Evidence indicates that the best predictor of positive adaptation is the psychological state of the patient with cancer before the initiation of any therapeutic regimens (13).

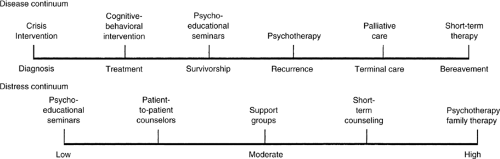

Figure 54.1 details potential interventions along the disease and distress continuums. The level of psychological vulnerability also falls along a continuum from low to high distress and should guide this selection of interventions (14). In addition, problem-solving interventions have been demonstrated to reduce distress among patients with cancer as well as among family members (15, 16). Prevalence studies demonstrate that one of every three newly diagnosed patients (regardless of prognosis) needs psychosocial or psychiatric intervention (17, 18, 19, 20). As disease advances, a positive relationship exists between the increase in the occurrence and severity of physiologic symptoms and the patient’s level of emotional distress and overall QOL. For example, a study of 268 patients with cancer having recurrent disease observed that patients with higher symptomatology, greater financial concerns, and a pessimistic outlook experience higher levels of psychological distress and lower levels of general well-being (21).

Table 54.1 Variables Associated With Psychosocial Adaptation | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In an effort to establish early identification of patients at high risk for poor adaptation, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) developed guidelines for the management of psychological distress among cancer patients across the disease continuum. These guidelines provide a framework for the development and implementation of psychosocial interventions based on the perspectives of psychiatry, social work, psychology, nursing, and pastoral care. Psychosocial screening serves as the mechanism to identify patients at higher levels of risk in order to provide interventions at a much earlier point in time. These guidelines can be accessed at http://www.nccs.org.

If distress levels can be identified through techniques such as psychosocial screening (22), patients can then be introduced into supportive care systems earlier in the treatment or palliative care process. Accordingly, any attempt to identify vulnerable patients and families in a prospective manner is worthwhile. Screening techniques are available through the use of standardized instruments which are able to prospectively identify patients and families that may be more vulnerable to the cancer experience (23). Preexisting psychosocial resources are critical in any predictive or screening process. In one approach, Weisman et al. (24) delineated key psychosocial variables in the format of a structured interview accompanied by a self-report measure (Table 54.1). However, in hospitals, clinics, or community agencies, which provide care to a high volume of patients and family members, a structured interview by a psychosocial provider is seldom feasible. Consequently,

brief and rapid methods of screening are necessary. Brief screening techniques that examine components of distress, such as anxiety or depression, can be incorporated into the routine clinical care of the patient. Early psychosocial interventions may be less stigmatizing to the patient, and more readily accepted by patients, families, and staff if screening identifies the management of distress as one component of comprehensive care (25). Screening is also a cost-effective technique for case identification in comparison to an assessment of all new patients (26). Although screening for distress and problems have received much attention recently, there are extremely few screening programs in place, even in comprehensive cancer centers. The Moores University of California, San Diego (UCSD) Cancer Center is one of the few cancer programs that is screening all new patients with cancer for common problems and related distress. Although presently performed with pencil and paper, this screening and triage process is now being automated through touch-screen computers. For each of the problems listed, a triage plan is in place and can be accessed during the clinic visit by the physician, nurse or social worker. Not surprisingly, the 10 most common problems in rank order manifested by the first 300 patients with cancer were: fatigue (feeling tired), fear and worry about the future, finances, pain, feeling down, depressed or blue, being dependent on others, understanding my treatment options, sleeping, managing my emotions, and solving problems due to my illness. Of particular note, although pain was not the most frequently endorsed problem, it was the most emotionally distressing.

brief and rapid methods of screening are necessary. Brief screening techniques that examine components of distress, such as anxiety or depression, can be incorporated into the routine clinical care of the patient. Early psychosocial interventions may be less stigmatizing to the patient, and more readily accepted by patients, families, and staff if screening identifies the management of distress as one component of comprehensive care (25). Screening is also a cost-effective technique for case identification in comparison to an assessment of all new patients (26). Although screening for distress and problems have received much attention recently, there are extremely few screening programs in place, even in comprehensive cancer centers. The Moores University of California, San Diego (UCSD) Cancer Center is one of the few cancer programs that is screening all new patients with cancer for common problems and related distress. Although presently performed with pencil and paper, this screening and triage process is now being automated through touch-screen computers. For each of the problems listed, a triage plan is in place and can be accessed during the clinic visit by the physician, nurse or social worker. Not surprisingly, the 10 most common problems in rank order manifested by the first 300 patients with cancer were: fatigue (feeling tired), fear and worry about the future, finances, pain, feeling down, depressed or blue, being dependent on others, understanding my treatment options, sleeping, managing my emotions, and solving problems due to my illness. Of particular note, although pain was not the most frequently endorsed problem, it was the most emotionally distressing.

Standardized measures of psychological distress can differentiate patients into low, moderate, or high degree of vulnerability. Patients with a low or moderate level of distress may benefit from a psychoeducational program, which can enhance adaptive capabilities and problem-solving skills; high distress patients possess more complex psychosocial needs that require brief therapy or family therapy along with psychotropic drug therapy for the patient. For some patients ongoing mental health services are essential, whereas other patients may require assistance only at critical transition points. Clinical practice suggests that virtually all patients could benefit from some type of psychosocial intervention at some point along the disease continuum, especially at the end of life. Psychosocial interventions include educational programs, support groups, cognitive-behavioral techniques, problem-solving therapy or education, and psychotherapy (27). To further facilitate the process of screening, the Brief Symptom Inventory-18 was developed to create greater ease with administration and scoring and to develop gender-based norms (28, 29).

The second continuum relates to the predictable phases of the disease process. This disease continuum extends from the point of diagnosis to cancer therapies and beyond. As patients move across this continuum, they may acquire experiences, knowledge, and skills that enable them to respond to the demands of their disease. The needs of a newly diagnosed patient with intractable symptoms differ significantly from a patient who has advanced disease and no further options for curative treatments.

The patient and family may be supported throughout the illness process and the family requires continuing support following the death of the patient. At times families are overwhelmed by the illness, and as a result are unable to effectively respond. For some families a death may represent a major loss of the family’s identity and may paralyze the family’s coping and problem-solving responses. Failure to respond and solve problems leads to a lack of control and may generate a significant potential for a chronic grief reaction (30). Although the disease continuum consists of specific points, Table 54.2 identifies a series of predictable and relevant crisis events and psychosocial challenges that occur as patients and families confront advanced disease.

Family Adaptability and Cohesion

The Circumplex Model of Family Functioning, as developed by Olson et al. (31), categorizes families in a manner that explains the variation in their behavior. Although not specifically developed for cancer, this model conceptualizes families’ responses to stressful events based on two constructs: adaptability, and cohesion. End-of-life care simultaneously generates significant stressors for both patients and families, especially in issues related to power, structure, and role assignments. Adaptability reflects the capability of a family to reorganize internal roles, rules, and power structure in response to a significant stressor. Given the impact of advancing cancer on the total family unit, families must frequently reassign roles, alter rules for daily living, and revise long-held methods for problem solving. Dysfunction in the family can relate to either low adaptability (rigidity) or excessively high adaptability (chaotic). A family characterized as rigid in its adaptability persists in the use of coping behaviors, such as frequent manifestations of anger, even when they are ineffective. Those that exhibit high adaptability create a chaotic response within the power structure, roles, and rules of the family; such families lack structure in their responses and attempt different coping strategies with every new stress. Although most families are in the more functional category of “structured adaptability,” 30% are rigid or chaotic. These latter families are likely to exhibit problematic behaviors such as excessive demands of staff time or interference with the delivery of medical care that the health care team may find difficult to manage (32).

The second construct of Olson et al.—cohesion—is indicative of the family’s ability to provide adequate support. Cohesion is the level of emotional bonding that exists among family members, and is also conceptualized on a continuum from low to high. Low cohesion (disengagement) suggests little or no connectedness among family members. A commitment to care for other family members is not evident and, as a result, these families are frequently unavailable to the medical staff for support of the patient or for participation in the decision-making process. At the other extreme, high cohesion (enmeshment) blurs the boundaries among family members. This results in the perception by health care providers that some family members seem to be just as affected by the diagnosis or treatment, or by each symptom, as the patient. Enmeshed families may demand excessive amounts of time from the health care team and be incapable of following simple medical directives. These families are not able to objectively receive and comprehend information which may be in the best interest of the patient. Also these families may assume a highly overprotective position in relation to the patient and may speak for the patient even when the patient’s self-expression could be encouraged.

When engaging families, it is necessary to gain an appreciation for the rules and regulations within each particular family. Each family has its own rules, regulations, and communication styles. In gaining an understanding of the role of the patient in the family, it is helpful to ask the patient to describe the specific responsibilities he or she performs in the family, especially during a crisis. Generalities are less informative than descriptions of the specific experiences and duties of each family member during a crisis. These queries enable the patient to openly communicate and objectively evaluate his or her role and importance in the family system and provide a clinical opportunity to assess ongoing progress or deterioration. Patients and families can usually tolerate even the worst news or the most dire prognosis as long as it is framed within a context in which the patient and family know how they are expected to respond and that the health care team will not abandon them.

Table 54.2 Advancing Disease and Psychosocial Treatment | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Impact of Physical and Psychological Symptoms

Patients with advanced illness experience pain, delirium, dyspnea, fatigue, nausea, anxiety, depression, sleeplessness, and many other symptoms that impair QOL. These noxious symptoms also compromise cognition, concentration, and memory (33), and override the underlying mental schema of patients. For the person in pain or acute physical distress, perception is confined to only the most immediate and essential elements of his or her sensory experience, and there is only a distant remnant of a past or future. The immediate need and goal is to stop or minimize the noxious experience. In some sense, pain, and other symptoms absorb the limited psychic energy of the patient, and valuable energy can only be made available if physical distress is effectively managed. The psychic life is subservient and dependent to the bodily experience. This is an important point for health care providers. Therefore, psychosocial interventions must simultaneously focus on physical symptoms in order to be effective. Furthermore, interventions that do not address the physical concerns of the patient may be unethical. The essence of psychosocial care is to raise the “bar” of what humanistic medical care means so that all of the concerns and needs of patients are effectively addressed and resolved. Unless physical and psychosocial distress are managed simultaneously, psychosocial interventions are less likely to be effective.

Moderate to severe pain is reported by 30–45% of patients undergoing (34) cancer treatments and 75–90% of patients with advanced disease (35). Pain seems to stand alone in its ability to gain the active attention of others although dramatically demonstrating a sense of being alone and vulnerable. This is especially true of patients with advanced disease, and their families. Although a patient is experiencing pain, another person only inches away is incapable of truly understanding what is so central and undeniable to the patient. This invisible and almost palpable boundary between the person in pain and his or her caregivers has significant implications for the quality and effectiveness of the therapeutic relationship (36).

Given that cancer pain can be adequately managed in almost all circumstances, its deleterious and at times life-threatening impact on the physical, psychological, and spiritual resources of both the patient and family are not only unnecessary but also evil. There is no known benefit to ongoing unrelieved pain. There are many known negative consequences. For example, O’Mahony et al. (37) found that the desire for death was correlated with ratings of pain and low family support but most significantly with depression. Given the relationship between pain and depression, the importance of adequate pain management can hardly be overstated. Recently Cobb et al. (38), in their comprehensive review of the delirium literature, found that poor pain control was identified as the number one cause or contributor for delirium. Given the obvious importance and prevalence of delirium as an indicator of QOL at the end of life, this is very important information.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree