Chapter 17 PSYCHOSOCIAL AND SPIRITUAL ASSESSMENT

INTRODUCTION

Psychosocial and spiritual assessments are addressed separately, but they can be interrelated in situations where active engagement and participation in spiritual experiences with other people enhances the psychosocial wellbeing of an older person. The underlying social integration that occurs when spiritual experiences are shared with others can be a protective factor against mental health problems. In this chapter, the term spirituality is used in a very broad sense to recognise that some people have spiritual experiences and practices, but do not subscribe to a recognised religion or system of faith and worship (e.g. Christian or Muslim).

PSYCHOSOCIAL FACTORS

A framework that has stood the test of time for conceptualising people’s needs, including psychosocial needs, is the work by Maslow (1970). According to Maslow, for normal human development to occur, the physical needs of nutrition and hydration have to be satisfied first and then the emotional needs of love, belonging and self-esteem can be met. After these basic needs are satisfied, then the person can continue to grow psychosocially by seeking meaning and fulfilment in their lives so they eventually reach the stages of self-actualisation and self-transcendence.

As people get older, how they perceive and address their psychosocial needs may influence their ability to remain independent, and how they deal with loneliness, social isolation and the development of mental health problems. Psychosocial support can vary enormously from a brief, weekly visit by one person for a housebound older person through to a person who has three or more social engagements outside the home almost every day. It is not the quantity of interactions but the quality that is the most important aspect. When an older person is struggling with mental health problems, it is high-quality psychosocial support that will act as a buffer in moderating the impact of the stress and will also have a strong influence on recovery. However, addressing an older person’s psychosocial needs is not just a simple matter of introducing and encouraging the support of other people or networks. Unwanted and stressful social engagements can also be detrimental to an older person’s mental health.

Ecomaps

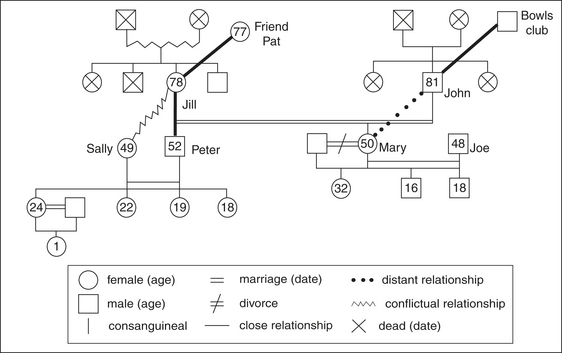

To determine the size, structure and strength of psychosocial networks, a good starting point is the use of an ecomap (Wright & Leahey 2000). The ecomap is an extension of the genogram, which outlines family relationships. The ecomap is a graphic depiction of contact, with not only family members, but also friends, social contacts, health services and any other significant contact. A lot of information can be contained in these diagrams. Information is recorded in squares or circles, which can be strategically placed or organised to show how all the relationships fit together. The strength of the relationships is signified by lines. Straight lines indicate strong relationships (the wider the line the stronger the relationship), while dotted lines indicate weak relationships and slashed lines indicate conflictual relationships. The frequency of contacts can also be noted on the diagram. See Figure 17.1 for an example of an ecomap.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree