Proximal Humerus Resection with Endoprosthetic Replacement: Intra-articular and Extra-articular Resections

Martin M. Malawer

James C. Wittig

Kristen Kellar-Graney

BACKGROUND

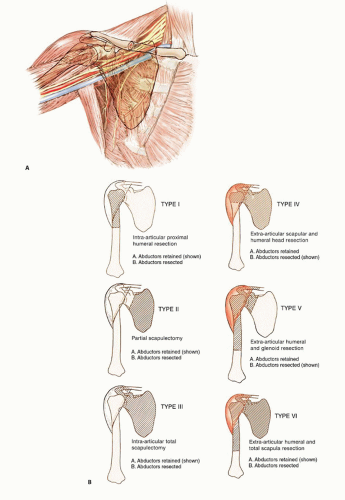

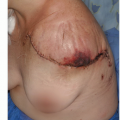

The proximal humerus is a common site for both primary osteosarcomas and chondrosarcomas and is the second most common site of metastatic disease involving long bones. Metastatic tumors occasionally involve the shoulder girdle and often are treated using the same resection and reconstruction techniques (FIG 1A).

Limb-sparing resection of the proximal humerus is challenging. Despite their complexity, these resections can be performed in about 95% of patients with high- or low-grade sarcomas. Amputations rarely are required.

Endoprosthetic reconstruction is the most common technique for reconstructing large proximal humeral defects. It is used following both intra-articular (type I) and extraarticular (type V) resections. This type of reconstruction is combined with local muscle transfers to create shoulder stability; cover the prosthesis; and provide a functional elbow, wrist, and hand (FIG 1B).

The surgical and anatomic considerations of limb-sparing procedures of the proximal humerus and the specific surgical techniques for type I and type V resection and reconstruction are described in this chapter. Total humeral replacement is described briefly.

The proximal humerus is one of the most common sites for high-grade malignant bone tumors in the adult, and it is the third most common site for osteosarcoma.2 Tumors in this location tend to have a significant extraosseous component. The proximal humerus also may be involved by metastatic cancer (especially renal cell carcinoma) and secondarily by soft tissue sarcomas, which require a resection similar to that used for primary bone sarcomas with extraosseous extension.

About 95% of patients with tumors of the shoulder girdle can be treated with limb-sparing resections.

The Tikhoff-Linberg resection and its modifications are limb-sparing surgical options for bone and soft tissue tumors in and around the proximal humerus and shoulder girdle. Portions of the scapula, clavicle, and proximal humerus are resected in conjunction with all muscles inserting onto and originating from the involved bones. Careful preoperative staging and selection of patients whose tumor does not encase the neurovascular bundle or invade the chest wall are required.

A classification system for resection of tumors in this location is described in FIG 1B. The most common procedure for high-grade sarcomas of the proximal humerus, type VB, is described.

We do not recommend type I resection for high-grade tumors due to the increased risk of local recurrence.

Optimal function is achieved with muscle transfers and skeletal reconstruction. A prosthesis is used to maintain length and stabilize the shoulder and distal humerus following resection. A stable shoulder with normal function of the elbow, wrist, and hand should be achieved following most shoulder girdle resections and reconstructions performed using the techniques described.

INDICATIONS

Indications for limb-sparing procedures of the proximal humerus and shoulder girdle include high-grade and some lowgrade bone sarcomas as well as some soft tissue sarcomas that secondarily invade bone.

Occasionally, solitary metastatic carcinomas to the proximal humerus and multiple metastatic carcinoma to the proximal humerus with no option of stabilization and fixation are best treated by a wide excision (ie, type I resection).

The decision to proceed with limb-sparing surgery is based on the location of the tumor and a thorough understanding of its natural history. Recently, we have treated patients with pathologic fractures with induction chemotherapy, immobilization, and limb-sparing surgery if there is a good clinical response and fracture healing.

CONTRAINDICATIONS

Absolute contraindications include tumor involvement of the neurovascular bundle or extensive invasion of the adjacent chest wall (FIG 2).

Extensive invasion of the muscles around shoulder girdle

Relative contraindications include chest wall extension, tumor contamination of the operative site from hematoma following a poorly performed biopsy or pathologic fracture, a previous infection, or lymph node involvement.

UNIQUE ANATOMIC CONSIDERATIONS

Resection and reconstruction of the proximal humerus and shoulder girdle is a technically demanding procedure.

The local anatomy of the tumor often determines the extent of the operation required. The surgeon should be experienced with all aspects of shoulder girdle anatomy and the unique considerations it may present.

Proximal Humerus

Malignant tumors often present with large soft tissue components (stage IIB) underneath the deltoid that extend

medially and displace the subscapularis and coracobrachialis muscles.3 Pericapsular and rotator cuff involvement occur early and must be evaluated.

Glenohumeral Joint

The shoulder joint appears to be more prone to intraarticular or pericapsular involvement by high-grade bone sarcomas than are other joints.

Four basic mechanisms exist for tumor spread: direct capsular extension, tumor extension along the long head of the biceps tendon, fracture hematoma from a pathologic fracture, and poorly planned biopsy.

These mechanisms place patients undergoing intra-articular resections for high-grade sarcomas at greater risk for local recurrence than those undergoing extra-articular resections. Therefore, it often is necessary to perform an extra-articular resection for high-grade bone sarcomas of the proximal humerus or scapula.

Neurovascular Bundle

The subclavian artery and vein join the cords of the brachial plexus as they pass underneath the clavicle.

Beyond this point, the nerves and vessels can be considered as one structure (ie, the neurovascular bundle). Large tumors involving the upper scapula, clavicle, and proximal humerus may displace the infraclavicular components of the plexus and axillary vessels.

Musculocutaneous and Axillary Nerves

The musculocutaneous and axillary nerves often are in close proximity or contact with tumors around the proximal humerus.

The musculocutaneous nerve is the first nerve that leaves between the teres major and minor to innervate the deltoid muscle posteriorly.

Tumors of the proximal humerus are likely to involve the axillary nerve as it passes adjacent to the inferior aspect of the humeral neck, just distal to the joint. Therefore, the axillary nerve and deltoid almost always are sacrificed during proximal humerus resections.

Radial Nerve

The radial nerve comes off the posterior cord of the plexus and continues anterior to the latissimus dorsi and teres major. Just distal to the teres major, the nerve courses into the posterior aspect of the arm to run between the medial and long head of the triceps.

Although most sarcomas of the proximal humerus do not involve the radial nerve, it must be isolated and protected prior to resection.

Axillary and Brachial Arteries

The axillary artery is a continuation of the subclavian artery and is called the brachial artery after it passes the inferior border of the axilla. The axillary vessels are surrounded by the three cords of the brachial plexus. The axillary artery typically leaves the lateral cord just distal to the coracoid process, passes through the coracobrachialis, and runs between the brachialis and biceps. Preservation of the musculocutaneous nerve and short head of the biceps muscle is important to ensure normal elbow function.

The path of this nerve may vary extensively (within 2 to 8 cm of the coracoid) and should be identified before any resection is performed because the nerve can easily be injured.

The axillary nerve arises from the posterior cord and courses, along with the circumflex vessels, inferior to the distal border of the subscapularis. It then is tethered to the proximal humerus by the anterior and posterior circumflex vessels.

Early ligation of the circumflex vessels is a key maneuver in resection of proximal humeral sarcomas because it allows the entire axillary artery and vein to fall away from the tumor mass.

Occasionally, anatomic variability in the location of the branches of the nerve may lead to difficulty in identification and exploration if the variation has not previously been recognized. A preoperative angiogram is helpful in determining vascular displacement and anatomic variability.

Final determination of tumor resectability is made at surgery. Early exploration of the neurovascular structures is performed following division of the pectoralis major muscle. This approach does not jeopardize subsequent formation of an anterior flap in patients who require forequarter amputation.

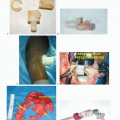

IMAGING AND OTHER STAGING STUDIES

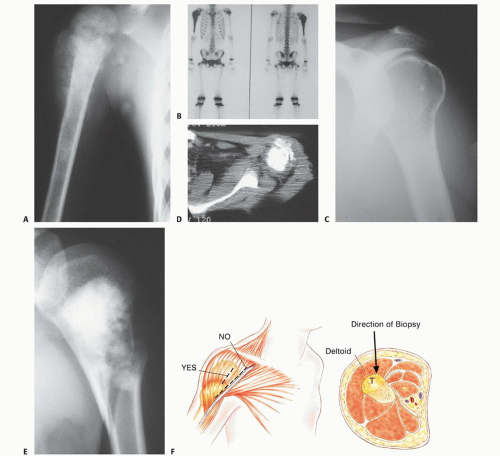

Appropriate imaging studies are key to successful resections of tumors of the proximal humerus and shoulder girdle (FIG 3A-E).

Computed Tomography

CT is most useful for evaluating cortical bone changes and is considered complementary to MRI in evaluating the chest wall, clavicle, and axilla for tumor extension (FIG 3D).

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

MRI is useful to identify intraosseous tumor extent, which is necessary for determining the length of bone resection. It is the best imaging modality for evaluation of soft tissue tumor involvement, especially around the glenohumeral joint, suprascapular region, and chest wall.

Bone Scintigraphy

Bone scintigraphy is used to determine the intraosseous tumor extent and to detect metastases (see FIG 3B).

Angiography

Angiography is useful for evaluation of tumor vascularity and tumor response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy. It also is essential for determining the relation of the brachial vessels to the tumor or the presence of anatomic anomalies. A brachial venogram also may be necessary if there is evidence of distal venous obstruction suggesting a tumor thrombus. It is also relevant in cases where the decision to amputate is conflictive.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree